Replacement of the Esophagus with Colon

Ronald H. R. Belsey

Indications

The use of colon for esophageal replacement is indicated when long-term survival of the patient can confidently be expected: in cases of type IB (long gap) and type II congenital atresia, after resection of benign strictures or tumors, for advanced functional disorders, after numerous previous failed antireflux procedures, and in certain cases of malignant obstruction with an apparently good prognosis after radical surgery. The right or left colon is available for replacement. Left colon is preferable to right for the following reasons: its smaller diameter, the more constant and reliable blood supply from the left colic artery, its adequate length for total esophageal replacement, and its better ability to propel a solid bolus.

Right colon can be used when left colon is debarred by intrinsic disease or previous surgery. Incorporation of terminal ileum in the transplant has been advocated, but inclusion of the ileocecal valve may hinder progression of the swallowed bolus. Ventemiglia and colleagues9 investigated preoperative angiography and found a marginal artery in only 6 (30%) of 20 studies on the right colon but in all 20 (100%) of the left colons studied. By autopsy injection studies, Nicks6 demonstrated frequent anomalies in the venous drainage from the right colon that might jeopardize the survival of the trans- plant.

Why use colon? The frequently used alternative organ is the stomach, entire or tubed. The advantages of the stomach as an esophageal substitute are its reliable blood supply and the simple technique, involving a single anastomosis. Disadvantages include high morbidity from anastomotic failures, a tendency to dilatation and defective propulsion, and frequent late complications such as recurrent esophagitis and stenosis, gastric ulceration, and hemorrhage.

The observed advantages of colon, especially left colon, are the fewer lethal anastomotic problems (leaks can heal spontaneously), the progressive improvement in propulsive functional capacity, and its suitability for use in children. These advantages outweigh the disadvantages of the more complicated operative technique, which involves three anastomoses.

Contraindications to colon interposition consist of the following:

Intrinsic colonic pathology. In practice, mild degrees of diverticulosis with no previous history of infection have not proved to be a significant contraindication.

Mesenteric endarteritis. The endarteritis is commonly associated with systemic hypertension. Routine preoperative angiography is not recommended. The condition of the left colic artery and the vascular supply to the left colon can be assessed more accurately at operation.

Subnormal colonic motility. In 15% of cases, colonic propulsive motility is subnormal. Preoperative detection of this defect currently is difficult. The history of bowel activity may be significant. Radiologic evidence of the rapidity or frequency of bowel evacuation is not a reliable guide. When perfected, motility studies of colonic function may provide essential information.

Jejunal interposition can be used for limited replacements, but variations in the vascular anatomy frequently debar it from extensive reconstructions.

In planning the reconstruction, the following features must be observed:

An isoperistaltic interposition is mandatory.

Protection of the vascular pedicle from mechanical obstruction by torsion, kinking, or tension is vital to the success of the technique.

Three routes for the reconstruction are available: mediastinal, transpleural, and retrosternal. The menace to the integrity of the pedicle is least in the more direct mediastinal route and greatest in the more tortuous retrosternal route.

A cologastric anastomosis incorporating an antireflux principle is essential to prevent peptic colitis.

The tailoring of the transplant should prevent any intrathoracic redundancy, which can lead to mechanical obstruction by kinking. Moderate redundancy of the intra-abdominal segment of the transplant is well tolerated.

The preferred anastomotic technique involves a single inverting layer of interrupted sutures of monofilament stainless steel wire or other nonirritating material. The advantages of wire are the complete lack of tissue reaction and the insignificant size and security of the knots.

Preoperative Preparation

The general measures necessary in the preparation of a patient for major thoracic surgery are universally accepted and need not be repeated. Less generally recognized is the importance of eliminating all oronasal foci of infection. The mouth is probably the most heavily contaminated cavity in the body. Every esophageal resection incurs a risk of mediastinal infection. After the extraction of septic teeth, the gums should be allowed to heal before the operation. In the present context, the major concern is the preparation of the colon as a transplant for esophageal replacement. The aim is an empty, dry colon to reduce the risk of peritoneal, pleural, or mediastinal contamination during the interposition procedure. Time should be allowed for a full standard colon preparation in every case for which a resection and replacement might prove to be indicated at thoracotomy. The need for preoperative antibiotic therapy is debatable. Neomycin has caused severe enteritis because of changes in bowel flora. In my experience, no increase in peritoneal or pleural infection has been observed after the omission of preoperative antibiotic therapy.

Operative Technique

Reconstruction with Left Colon

Exposure

The extended left sixth interspace thoracotomy incision—with division of the costal margin at the anterior limit of the sixth interspace, peripheral detachment of the diaphragm from its origin on the chest wall, and extension of the incision through the oblique muscles as far as the lateral margin of the rectus sheath—affords adequate exposure of the entire left hemithorax and the upper abdomen, with access to the organs available for reconstruction: the stomach, left colon, or jejunum. In those patients who have not had previous abdominal surgery, it may not be necessary to carry the incision across the costal margin. The spleen recedes beneath the posterior part of the diaphragm and is protected from injury.

Exploration

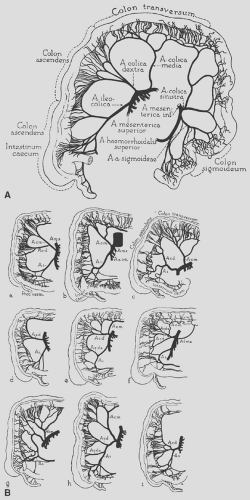

The position and extent of the esophageal lesion is determined by the preoperative studies. Exploration of the mediastinum is deferred until later in the procedure. The first step is examination of the splenic flexure of the left colon: the adequacy of its preparation, the condition of the left colic and middle colic arteries by palpation of pulsation and compressibility, and the visible pulsation of the marginal artery and branches (Fig. 141-1). The marginal artery distal to its origin from the left colic artery, the main trunk of the middle colic artery, and the marginal artery to the right of the connections of the middle colic are all occluded temporarily by atraumatic vascular clamps to isolate the supply from the left colic vessels. Further inspection confirms the adequacy of the blood supply. The clamps are promptly removed.

Mobilization of the Left Colonic Transplant

This step is done before the mediastinum is explored. Postponing mediastinal dissection and mobilization of the esophagus

prevents considerable blood loss from periesophageal vascular adhesions during the abdominal phase of the procedure. The greater omentum is detached from the colon from the splenic flexure to a point well to the right of the middle colic artery. The descending colon is mobilized by division of the peritoneal reflection along the lateral margin as far down as the junction of the descending with the sigmoid colon, where the colon is anchored to the posterior abdominal wall by a condensation of peritoneal tissue. With determined retraction of the abdominal wall, this band can be divided under direct vision. Mobilization of the splenic flexure and transverse colon, with its mesocolon, from the posterior abdominal wall necessitates division of the various ill-defined and irregular bands of vascular areolar tissue. The major vessels are contained in the mesocolon.

prevents considerable blood loss from periesophageal vascular adhesions during the abdominal phase of the procedure. The greater omentum is detached from the colon from the splenic flexure to a point well to the right of the middle colic artery. The descending colon is mobilized by division of the peritoneal reflection along the lateral margin as far down as the junction of the descending with the sigmoid colon, where the colon is anchored to the posterior abdominal wall by a condensation of peritoneal tissue. With determined retraction of the abdominal wall, this band can be divided under direct vision. Mobilization of the splenic flexure and transverse colon, with its mesocolon, from the posterior abdominal wall necessitates division of the various ill-defined and irregular bands of vascular areolar tissue. The major vessels are contained in the mesocolon.

Isolation of the Blood Supply to the Transplant

After complete mobilization, the vascular anatomy of the left colon can be determined accurately. The continuity of the marginal artery in the region of the splenic flexure is confirmed. The mesocolon is divided above and below the left colic vessels. The division is extended to the right as far as the left branch of the middle colic artery, maintaining a 1- to 2-cm fringe of mesocolon to protect the marginal artery. The left colic artery, arising from the inferior mesenteric artery, usually supplies two branches to the marginal artery. The marginal artery is divided distal to or below both branches of the left colic. The division of the right-hand end of the marginal artery, or the left branch of the middle colic, is deferred until the esophagus is liberated from the mediastinum and the extent of the resection and length of transplant necessary for replacement are determined.

Pyloromyotomy

At this stage of the operation, a pyloromyotomy is performed. In the absence of a gastrostomy or abdominal wall adhesions resulting from previous gastric surgical intervention, the myotomy is performed on the anterior aspect of the pylorus. In the presence of a gastrostomy or extensive adhesions, a myotomy can be performed with equal effectiveness on the posterior aspect of the sphincter through the lesser sac, which is opened extensively during the mobilization of the colon. A pyloromyotomy is a satisfactory gastric drainage procedure and does not incur the risk of duodenal reflux that may follow a pyloroplasty.

Mobilization of the Esophagus

The preliminary intra-abdominal maneuvers having been completed, attention can return to the mediastinum. Mobilization of the esophagus for the excision of benign lesions is easily achieved through the left thoracotomy incision. Most malignant lesions except those directly involving the aortic arch are equally accessible. In the latter case, a right thoracotomy combined with a separate laparotomy incision may be preferable. The single-incision approach has obvious advantages. In the management of benign lesions by left colon replacement, only the diseased segment is excised, followed by an intrathoracic esophagocolic anastomosis. Subsequent anastomotic problems are less menacing and can be managed conservatively.

Many bypass procedures with colon call for a long segment of transplant capable of reaching the cervical esophagus or even the pharynx in some cases. At this stage, the probable length of the transplant necessary for replacement or bypass can be estimated. An excessively long transplant can be tailored to a suitable length; if it is too short, tension on the anastomoses may promote complications.

Closure of the Cardia

The esophagogastric junction is divided. The stomach is repaired with two rows of inverting sutures. The cardia is not used for the subsequent cologastric anastomosis. The lower esophagus is ligated to prevent contamination of the mediastinum and pleura. If a bypass procedure is planned with the esophagus left in situ, the cardia is not divided, because it is important to maintain drainage of the lower segment between the stricture and the cardia to avoid creation of a closed loop of obstructed esophagus and the potential risk of a blowout.

Division of the Colon and Isolation of the Transplant

The point of division of the marginal artery and transverse colon at the proximal end of the planned transplant is selected. For a short-segment transplant, this point is just to the left of or distal to the point where the left branch of the middle colic joins the marginal artery. A single ligature is placed on the marginal artery, and the vessel is divided on the transplant side of the ligature. The divided vessel is allowed to bleed momentarily, affording the most graphic demonstration of the adequacy of the blood supply to the transplant from the left colic artery—a more reliable indication than that afforded by the use of any form of flowmeter. The vessel is picked up and ligated.

Preparation of the long-segment transplant for total replacement involves a different procedure. The marginal artery between the two branches of the middle colic artery is carefully examined and assessed. If the marginal artery is well developed and continuous, the left branch of the middle colic is divided near its origin from the main trunk of the middle colic, the intervening mesocolon is divided, and the marginal artery is ligated close to the point at which the right branch of the middle colic joins the marginal artery. Selection at this point results in a transplant long enough to reach the pharynx, if necessary, with retention of the right branch of the middle colic. The marginal artery is allowed to bleed momentarily, as noted in the previous paragraph, to confirm the adequacy of the blood supply. Rarely, the marginal artery between the two branches of the middle colic may be defective or replaced by a plexus of vessels, the adequacy of which in terms of blood supply to the proximal end of the transplant may prove difficult to assess. In this situation, the two branches of the middle colic are retained to substitute for the defective margin. The main trunk of the middle colic is cleared and divided well proximal to the point of division into the two main branches. The continuity of the supply to the colon is maintained through the juncture of the two branches of the middle colic.

Any palpable residual colonic contents are milked from the segment destined for transplantation and into the descending colon below the level where it will be divided. The length of transplant having been determined, the colon is divided at the appropriate sites between two pairs of Potts aortic clamps. The descending colon is divided below both branches of the left colic artery. The advantages of Potts aortic clamps are the narrow blades and the minimal trauma they cause to the colonic tissue.

Colocolic Anastomosis

The continuity of the colon is restored by end-to-end anastomosis of the transverse colon to the descending colon. The divided ends of the bowel are approximated and held in this position by a seromuscular suture placed through the mesenteric border of the two segments. The Potts clamps are removed and any residual fecal matter carefully mopped out of the now open bowel segments. Pledgets of Gelfoam may be inserted into the proximal transverse and descending colon to absorb any residual liquid fecal matter and reduce the risk of contamination during the anastomosis. These pledgets pass naturally when bowel function returns. Specimens are taken for culture as a guide to postoperative antibiotic therapy if necessary. The blood supply to the bowel segment is checked, especially for any evidence of venous engorgement, suggesting interference with the venous drainage caused by tension or rotation. An end-to-end single-layer inverting anastomosis is achieved by interrupted sutures of 5–0 or 6–0 monofilament stainless steel wire with the reef knots tied on the luminal side, commencing at the mesenteric border approximated by the initial suture and working around each side alternatively until finally the anastomosis is completed by two or three sutures placed on the antimesenteric margins from the outside, with careful inversion of the colonic mucosa.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree