Renal Artery Aneurysm

PETER K. HENKE

Presentation

A 45-year-old woman, G6/P5, is evaluated for vague right upper quadrant pain. Past medical history includes hypertension controlled with two medications, including an angiotensin-converting enzyme (ACE) inhibitor and a diuretic. The patient denies any history of tobacco use, diabetes, and hyperlipidemia, and there is no family history of any aneurysmal or other major vascular disease. She is perimenopausal.

CT Scan

CT Scan Report

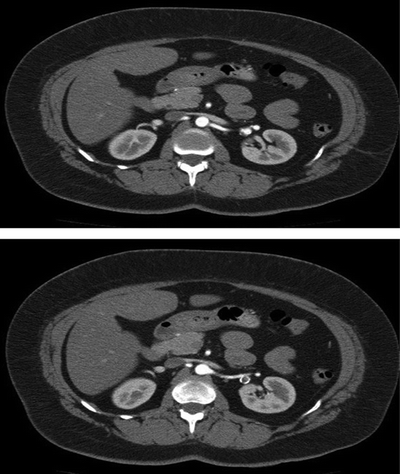

A computed tomographic (CT) scan shows no evidence of gallbladder or liver pathology, but there is an incidental finding of a right renal artery aneurysm (RAA) approximately 2.5 cm in size, not noted on a prior right upper quadrant ultrasound (Fig. 1), and other mesenteric aneurysms are identified.

FIGURE 1 Contrast CTA showing right renal artery aneurysm at bifurcation of main renal artery.

Further Diagnostic Workup

No hematuria is detected on urinalysis, and serum creatinine is normal. An arteriogram should be obtained in these patients to delineate the renal anatomy with dedicated catheter injections and multiple projections of both renal arteries. Alternatively, high-resolution CTA can be used with good fidelity for main artery aneurysms, obviating the need for angiogram (Fig. 2).

FIGURE 2 A moderate distal left renal artery aneurysm is found; size is approximately 2.1 cm.

Arteriogram

Arteriogram Report

A large right RAA at the bifurcation of the main renal artery, and a smaller left RAA in a first-order branch (Fig. 3). No other intra-aortic pathology is identified.

FIGURE 3 Contrast arteriogram showing saccular aneurysm at main bifurcation of the right renal artery (A, B).

Treatment Considerations

Because this patient is just beyond childbearing age, indications for repair are slightly less compelling than if premenopausal, where repair is definitely indicated. The main risk with RAA is rupture. If this occurs, mortality ranges between 10% and 15%. Rupture risk is higher in premenopausal women, and kidney loss is high in the setting of rupture, ranging between 50% and 100%. Although endovascular repairs have been documented, this does not seem appropriate for most RAA, because they are often fusiform and not amenable to coil embolization. A technical mishap may cause total kidney infarction. Recent reviews suggest that this option is reasonable in high-risk patients, and perhaps better in those with a proximal RAA, that can be treated with a covered stent.

The patient’s RAA is a size that is suitable for repair, given that she otherwise has few cardiovascular risk factors. Various methods for repairing these lesions have been described including ex vivo reconstruction with kidney autotransplantation, but it is the author’s practice to perform the repair in situ, using aneurysm resection, primary repair, and/or bypass as the individual anatomy dictates.

Surgical Approach

At operation, a lumbar roll is placed to create a lumbar lordosis. A transverse supraumbilical incision allows for excellent exposure of the kidneys. An extensive Kocher maneuver is used to expose the right kidney and renal vasculature. Care must be taken to fully dissect the RAA from surrounding renal venous and hilar structures. A right RAA resection with primary repair is performed.

FIGURE 4 Contrast arteriogram performed on post operative day 7 showing patent arterial system, with no evidence of aneurysm.