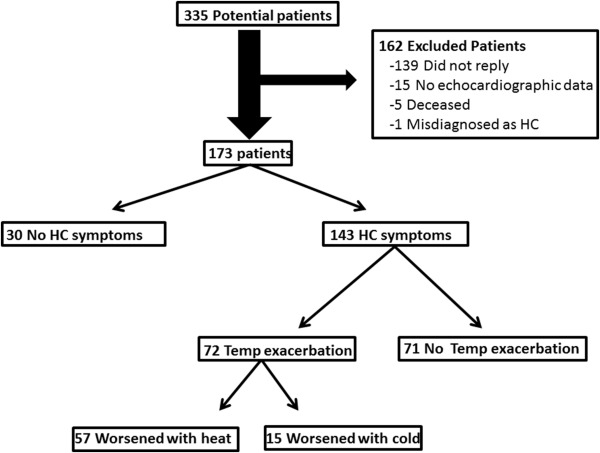

Warm temperatures induce peripheral vasodilation, decrease afterload, and may concurrently increase the left ventricular outflow tract (LVOT) gradient. We aimed to assess the impact of subjective ambient temperature on hypertrophic cardiomyopathy (HC) symptoms and determine whether they were associated with LVOT gradient, patient quality of life (QOL), and risk of sudden cardiac death (SCD). We identified consecutive patients with HC presenting to a tertiary referral center. Of the 173 patients in the study, 143 (83%) had HC symptoms, with ambient temperature change worsening symptoms for 72 patients (50%). Symptom exacerbation occurred only with heat for 57 (79%), whereas symptoms were exacerbated with cold only or with cold and heat equally for 15 (21%). Patients affected by any temperature exacerbation more commonly were women (p = 0.009), had a lower QOL (p = 0.04), had a family history of HC (p = 0.007), or underwent myectomy (p = 0.01). A greater proportion of patients with heat-only exacerbation had a family history of HC (p = 0.005) and SCD (p = 0.05). The presence of an LVOT gradient either at rest or with provocation was similar in all groups. In conclusion, although no appreciable difference in LVOT gradients were observed between patient groups, approximately half of the patients with HC reporting symptoms at baseline noted worsening of symptoms with temperature changes, with >75% describing heat-induced symptom exacerbation. Furthermore, affected patients more frequently were women, underwent surgical intervention and device implantation, and had an overall lower QOL.

A subset of patients with hypertrophic cardiomyopathy (HC) report aggravation of symptoms in warmer temperatures. However, scientific investigations regarding the prevalence of this symptom and its bearing on functional status and clinical outcome are lacking. Clinical history often shows exacerbation of symptoms in warm temperatures, with subsequent improvement on moving to cooler environments. The proposed pathophysiology is that cooler temperatures induce peripheral vasoconstriction, thereby increasing afterload and ultimately decreasing the left ventricular outflow tract (LVOT) gradient. In contrast, warmer environments promote vasodilation, decrease cardiac afterload, and increase the severity of LVOT obstruction. This present investigation had 2 objectives. First, we aimed to determine the prevalence of temperature-dependent symptom variation in patients with HC. Second, we aimed to characterize the association between subjective, temperature-dependent symptom change and clinical characteristics, particularly LVOT gradient, quality of life (QOL), and risk of sudden cardiac death (SCD). If significant correlations do exist, this study strives to be the foundation for further prospective work that examines real-time LVOT gradient changes in patients with HC, dependent on variation of environmental temperature, or if not, it possibly will help determine future directions for physiological investigations.

Methods

The Mayo Clinic Institutional Review Board approved the study. Written, informed consent was obtained from each patient. Consecutive patients with HC, evaluated at Mayo Clinic (Rochester, Minnesota) from January 1, 2002, to December 31, 2006, were eligible for this study. Exclusion criteria were age <18 years and lack of echocardiographic data before any surgical intervention for HC.

All eligible patients in the database were surveyed through telephone. All surveys were conducted by a single investigator (JPB), who was masked to all patient variables except age and gender at the time the survey was conducted. The survey consisted of 3 questions:

- 1)

Prior to having any therapeutic procedure performed for your HC, have you experienced any symptoms (shortness of breath, angina, presyncope, syncope, and chest tightness)? (Yes/No)

- 2)

Prior to having any therapeutic procedure performed for your HC, on a hot day, have you felt that HC-related symptoms (shortness of breath, presyncope, syncope, angina, and chest tightness) were better, worse, or unchanged?

- 3)

Prior to having any therapeutic procedure performed for your HC, on a cold day, have you felt that HC-related symptoms (shortness of breath, presyncope, syncope, angina, and chest tightness) were better, worse, or unchanged?

All relevant clinical variables, including demographics, medical co-morbidities, pertinent family and social history, and medications, were collected prospectively for all patients in the study.

All echocardiograms were performed at a single tertiary referral center, as described previously. Briefly, baseline echocardiographic features of the study population were compared. The echocardiographic parameters collected included structural measurements. LVOT gradient either at rest or with provocation were derived from the continuous-wave Doppler velocities.

The Minnesota Living With Heart Failure questionnaire was used to objectively measure the patients’ QOL. We compared patients with and without temperature-related symptom change to assess the effect of temperature on QOL.

LVOT gradient at rest was defined as >30 mm Hg, and provoked obstruction was defined as a gradient >50 mm Hg. Provocative measures included either the Valsalva maneuver or administration of amyl nitrite.

The previously validated SCD risk score was used to calculate the 5-year risk of SCD for each patient in the study. The risk score encompassed 7 features: (1) age, (2) maximum LVOT gradient, (3) severity of LV hypertrophy, (4) presence of nonsustained ventricular tachycardia, (5) unexplained syncope, (6) family history of SCD, and (7) left atrial diameter.

Data were summarized as mean ± SD for continuous variables and as number and percent for categorical variables. Categorical data were analyzed using the 2-tailed Pearson’s chi-square or Fisher’s exact test. Association of continuous variables was examined using simple linear regression analysis. When indicated, nonparametric tests were used. Analyses were completed using SAS (version 9.2) and JMP (version 11.2.1) (SAS Institute Inc.). Statistical significance was established a priori at p ≤0.05.

Results

We surveyed patients with HC regarding temperature and HC symptoms. We contacted 335 patients, and 173 (52%) were included in the study. Reasons for excluding 162 patients are shown in Figure 1 . HC symptoms were noted by 143 patients (83%), and of these patients, 72 (50%) noted symptom exacerbation in temperature extremes. Most of these patients (n = 57 [79%]) thought that their symptoms worsened only with heat, whereas the remaining patients (n = 15 [21%]) thought that their symptoms were exacerbated either by cold temperature alone or by cold and heat equally ( Figure 1 ). Clinical and echocardiographic characteristics of patients are listed in Table 1 .

| Variable | No Temperature Symptoms (n=101) | Any Temperature-Associated Exacerbation (n=72) | Heat-Associated Exacerbation Only (n=57) | Cold or Equal Exacerbation (n=15) ∗ | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Value | P Value † | Value | P Value † | Value | P Value † | ||

| Age, mean ± SD, years | 55±16 | 52±14 | .16 | 51±5 | .12 | 55±12 | .92 |

| Male sex | 69 (68%) | 35 (49%) | .009 | 31 (54%) | .005 | 9 (60%) | .52 |

| Quality of life score (mean ± SD ‡ ) | 26±26 | 36±26 | .04 | 33±25 | .20 | 48±27 | .01 |

| Angina class III/IV | 9 (9%) | 3 (4%) | .23 | 0 (0%) | .02 | 3 (20%) | .19 |

| Dyspnea class III/IV | 38 (38%) | 32 (44%) | .37 | 25 (44%) | .44 | 7 (47%) | .50 |

| Presyncope | 49 (49%) | 40 (56%) | .36 | 32 (56%) | .36 | 8 (53%) | .73 |

| Syncope | 19 (19%) | 12 (17%) | .72 | 11 (19%) | .94 | 1 (7%) | .25 |

| Heart failure | 5 (5%) | 6 (8%) | .37 | 4 (7%) | .59 | 2 (13%) | .20 |

| Coronary artery disease | 15 (15%) | 7 (10%) | .32 | 5 (9%) | .27 | 2 (13%) | .87 |

| Diabetes mellitus | 6 (6%) | 2 (3%) | .33 | 2 (4%) | .50 | 0 (0%) | .33 |

| Hypertension | 49 (49%) | 26 (36%) | .10 | 23 (40%) | .32 | 3 (20%) | .05 |

| Family history of HC | 24 (24%) | 21 (29%) | .007 | 26 (46%) | .005 | 5 (33%) | .43 |

| Family history of SCD | 14 (14%) | 18 (25%) | .06 | 15 (26%) | .05 | 3 (20%) | .53 |

| Ventricular septum ≥30 mm | 8 (8%) | 1 (1%) | .06 | 1 (2%) | .11 | 0 (0%) | .26 |

| LVOT obstruction at rest or with provocation. | 68 (67%) | 50 (69%) | .77 | 39 (68%) | .89 | 11 (73%) | .64 |

| LVOT obstruction at rest | 47 (47%) | 36 (50%) | .65 | 28 (49%) | .75 | 8 (53%) | .62 |

| LVOT obstruction with provocation | 21 (21%) | 14 (19%) | .83 | 11 (19%) | .82 | 3 (20%) | .94 |

| 5-Year SCD risk, mean ± SD | 3±2 | 5±5 | .20 | 5 ±6 | .14 | 4 ±3 | .95 |

| β-blocker | 67 (66%) | 49 (68%) | .81 | 37 (65%) | .86 | 12 (80%) | .29 |

| Calcium channel blocker | 24 (24%) | 21 (29%) | .43 | 16 (28%) | .55 | 5 (33%) | .52 |

| Disopyramide | 6 (6%) | 5 (7%) | .79 | 3 (5%) | .86 | 2 (13%) | .29 |

| Ventricular septal ablation | 10 (10%) | 11 (15%) | .29 | 8 (14%) | .44 | 5 (33%) | .42 |

| Septal myectomy | 24 (24%) | 30 (42%) | .01 | 20 (35%) | .13 | 10 (67%) | .002 |

| Pacemaker | 9 (9%) | 14 (19%) | .04 | 12 (21%) | .03 | 2 (13%) | .63 |

| Internal cardioverter defibrillator | 10 (10%) | 15 (21%) | .04 | 13 (23%) | .03 | 2 (13%) | .69 |

| NSVT/VT | 11 (11%) | 15 (21%) | .08 | 12 (21%) | .07 | 3 (20%) | .39 |

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree