Tingling

Aching

Burning

Muscle cramps

Swelling

Throbbing

Heaviness

Itching

Restless legs

Tiredness

Fatigue

Table 4.2 outlines differential diagnostic considerations for lower extremity pain and discomfort. Tables 4.3 and 4.4 outline the differential diagnoses of unilateral and bilateral leg swelling, respectively. Table 4.5 outlines the differential diagnosis of leg ulcers. Skin changes in the ankle area are often due to chronic venous insufficiency, but each skin sign has a differential diagnosis of its own, and dermatology consultation should be considered if chronic venous insufficiency cannot be ruled in. Leg ulcers can also be caused by skin cancer, or venous ulcers can become malignant [2]. It is not clear from the literature when to biopsy, but skin biopsy should be considered for leg ulcers which do not heal despite appropriate management and patient compliance and for nonhealing leg ulcers in unusual locations.

Table 4.2

Differential diagnosis of lower extremity pain and discomfort

Deep or superficial venous thrombosis |

Peripheral arterial disease |

Iliocaval obstruction |

Pelvic congestion syndrome |

Proximal venous reflux (i.e., branches of the internal iliac vein) |

Vascular malformation |

Nutcracker syndrome |

Chronic compartment syndrome |

Neuralgia (i.e., sciatica) |

Complex regional pain syndrome |

Restless legs syndrome |

Musculoskeletal (i.e., muscle/tendon/ligament sprain, muscle pain, osteoarthritis, rheumatoid arthritis) |

Cellulitis |

Table 4.3

Differential diagnosis of unilateral leg swelling

Chronic venous insufficiency |

Deep venous thrombosis |

Iliocaval obstruction |

Lymphedema |

Lipedema |

Baker’s cyst |

Cellulitis |

Orthopedic trauma |

Table 4.4

Differential diagnosis of bilateral leg swelling

Bilateral chronic venous insufficiency |

Congestive heart failure |

Pulmonary hypertension |

Protein-losing nephropathy |

Liver cirrhosis |

Obesity |

Table 4.5

Differential diagnosis of leg ulcer

Venous ulcer |

Peripheral arterial disease |

Neuropathic ulcer |

Pressure ulcer |

Skin cancer |

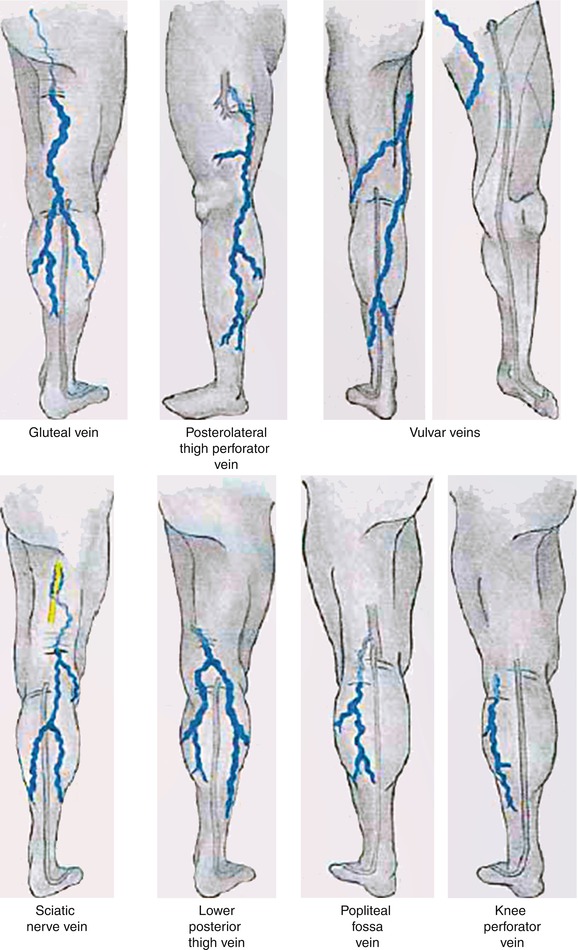

More advanced CVD, measured as increased CEAP class, is associated with more areas of reflux. Saphenous reflux is common in all CEAP classes. The prevalence of perforator and deep venous reflux increases with increasing CEAP class [3]. The most common pattern of saphenous reflux involves the great saphenous vein (GSV) (Fig. 4.1). Reflux in the small saphenous vein (Fig. 4.2) or anterior accessory GSV (Fig. 4.3) is also common. However, crossover involvement occurs, and each patient with suspected CVD merits a duplex ultrasound to determine if they meet the typical pattern [4]. Non-saphenous reflux (Fig. 4.4) occurs in around 10 % of patients [5].

Fig. 4.1

The classic great saphenous vein (asterisk) pattern

Fig. 4.2

Classic small saphenous vein reflux pattern

Fig. 4.3

The anterior accessory great saphenous vein (asterisk), when present, runs superficial to the femoral vessels

Venous symptoms can also be caused by venous sources other than lower extremity reflux or obstruction. Iliocaval obstruction should be considered in patients with venous symptoms with minimal or no reflux on infrainguinal ultrasound. Pelvic congestion syndrome can present with pelvic pain or varicosities or lower extremity varicosities which can be followed with ultrasound above the inguinal ligament. A vascular malformation usually presents at birth or puberty (due to hormonal changes) and can also be suggested by unusual anatomy seen on ultrasound. Reflux of tributaries of the internal iliac vein can cause varicosities on the buttocks or pelvic areas.

4.3 Medical Management

Multiple conservative measures have been recommended for patients with CVD, including compression, leg elevation, exercise, diet and weight loss, and analgesics. Compression options include elastic compression stockings, inelastic bandaging, and pneumatic compression. Prescription strength compression stockings start at 20–30 mmHg (Class 1) and are followed by 30–40 mmHg (Class 2), 40–50 mmHg (Class 3), and 50+ mmHg (Class 4). In general, compression at 20–30 mmHg seems effective for symptomatic varicosities, while 30–40 mmHg is preferred if tolerated for those with venous ulcers or leg swelling [1]. Knee-high length is often used due to greater ease in getting the stocking on, but thigh and pantyhose styles are also available. Compression therapy improves symptoms and quality of life in patients with simple symptomatic varicosities, but it does not reverse disease [6]. In patients with venous ulcers, compression accelerates healing and reduces ulcer recurrence risk [7]. Compression has not been shown to reduce varicosity recurrence rates or slow disease progression [6].

Compression therapy is contraindicated in patients with significant peripheral arterial disease, congestive heart failure, or active infection at the site. Patient compliance and difficulty getting the stocking on can be a major problem, so providers should carefully explain the benefits to patients. Interventional ablation of symptomatic reflux is more effective in improving quality of life than compression and lifestyle modification [8]. Despite the data, third-party payers often require a “trial” of conservative measures, such as compression, before ablation can be performed.

Exercise has been advocated under the hypothesis that making the calf muscle stronger, even in the presence of malfunctioning venous valves from reflux, may improve overall calf muscle pump function. In patients with venous ulcers, improving ankle range of motion and muscle strength improves venous hemodynamic parameters but has not yet been clearly shown to affect clinical outcomes [9].

Table 4.6 lists venoactive medicines. Studies on these medicines are limited, none are FDA approved for venous reflux disease, and many are not available in the USA [1].

Table 4.6

Venoactive medicines

Horse chestnut seed extract (aescin) |

Flavonoids – rutosides, diosmin, hesperidin

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree

Get Clinical Tree app for offline access

Get Clinical Tree app for offline access

|