Recurrent Carotid Stenosis

ANDY LEE and RAUL J. GUZMAN

Presentation

A 61-year-old man with a history of hypertension and coronary artery disease previously underwent bilateral carotid endarterectomies (CEA). His most recent CEA was performed on the left side 12 months ago. The right CEA was performed 2 years ago. He presents to your office for routine follow-up. On questioning, he admits to having two episodes of left eye blindness over the last month that each resolved over 10 to 15 minutes. Physical examination is notable for a left-sided cervical bruit. A carotid duplex ultrasound is performed.

Carotid Duplex Ultrasound Scan Report

Right common and internal carotid arteries without significant stenosis.

Left common carotid artery (distal): 80% to 99% stenosis.

Left internal carotid artery: 15% to 49% stenosis.

Differential Diagnosis

Recurrent carotid stenosis has an incidence of 4% to 16% in patients evaluated by serial duplex ultrasound following CEA. As patients with recurrent stenosis are typically asymptomatic, this reported incidence varies widely depending on the measurement criteria, methods, and duration of postoperative follow-up. Restenosis identified within the immediate postoperative period likely represents an incomplete endarterectomy with residual disease or technical defect after surgery. The characteristic homogeneous neointimal lesion seen in restenosis is usually discovered in patients experiencing recurrence within the first 3 years after endarterectomy. Late recurrences are more often due to progressive atherosclerosis.

In symptomatic patients, the differential diagnosis for stroke or transient ischemia attack following CEA includes recurrent carotid stenosis, new-onset atrial fibrillation (or other cardiac sources of embolic disease), vasculitis, and lacunar infarction.

Workup

The diagnosis of recurrent carotid stenosis is most commonly made on routine postoperative surveillance using duplex ultrasound. According to the Society for Vascular Surgery (SVS) clinical guidelines, patients undergoing CEA should be followed by exam and carotid duplex ultrasound testing within 30 days after their procedure. Patients without significant hemodynamic abnormality on initial duplex will usually have the study repeated in 6 months and thereafter on a yearly basis. Studies demonstrating stenosis greater than 50% should be repeated every 6 months or sooner if symptoms occur. A new cervical bruit that develops in an asymptomatic patient after CEA should be promptly evaluated by duplex ultrasound for recurrent carotid stenosis.

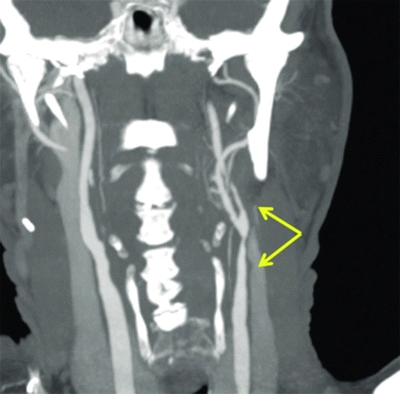

Adjunctive imaging modalities, such as computed tomography, MRI, and contrast angiography, may be employed when the duplex ultrasound does not provide sufficient anatomic definition or when there is a question about the proximal or distal vasculature. Computed tomography angiography (CTA) can provide excellent anatomical detail, especially when considering an endovascular approach. Physical examination should include a careful neurologic evaluation with a focus on cranial nerves to assess for stroke or any postoperative deficits.

Up to 50% of patients undergoing reoperation for recurrent carotid stenosis have an asymptomatic, high-grade lesion that was incidentally discovered through duplex ultrasound screening. Closure by patch angioplasty at the time of primary CEA has been shown to reduce the risk of developing restenosis. Data from the Carotid Revascularization Endarterectomy versus Stent Trial (CREST) suggest that female sex, hypertension, diabetes, and dyslipidemia were risk factors for recurrent stenosis after stenting or endarterectomy. Smoking has also been shown to be an independent predictor of restenosis but only after CEA.

Case Continued

The patient is scheduled for CTA to further evaluate his cerebrovascular anatomy.

CT Angiogram Report

The right common carotid artery (CCA) and internal carotid artery (ICA) are patent with mild calcified plaque and minimal luminal narrowing.

The left distal CCA shows an 80% stenosis. The left ICA is patent with 2 cm luminal narrowing but no focal stenosis (Fig. 1).

Recurrent Carotid Stenosis, Symptomatic

Diagnosis and Treatment

Several factors are considered when selecting the most appropriate treatment for recurrent carotid stenosis. Interval since CEA, severity of stenosis, medical comorbid conditions, status of the contralateral carotid, and presence or absence of symptoms are the key considerations. Asymptomatic, low-grade, or immediate-grade lesions are usually managed using antiplatelet therapy. Intervention should be considered for high-grade (greater than 80%) or symptomatic lesions, especially those associated with contralateral carotid occlusion. Preoperative imaging plays an essential role in characterizing the recurrent lesion, and these anatomic data must be considered in combination with the history and comorbid conditions of the individual patient in selecting the best method of intervention.

Redo CEA with patch angioplasty is the standard operative approach used to treat recurrent carotid stenosis. It carries a risk for cranial nerve injury in 7% to 20% of patients. Interestingly, data from regional databases with larger sample sizes have suggested that redo CEA is associated with higher rates of stroke/death/MI compared with primary CEA, but there was no difference in cranial nerve injury.

More recently, carotid angioplasty and stenting (CAS) has been employed in the treatment of postendarterctomy restenosis. In cases of early restenosis (less than 3 years), the homogenous lesion from myointimal hyperplasia is thought to be smooth and less likely to result in lesion embolization during wire traversal. The method allows for the avoidance of redo surgery in those patients with dense scar tissue. National vascular registry data show better outcomes for carotid artery stenting in restenotic compared with primary lesions. Other appealing features of carotid stenting include the use of local anesthesia making it a suitable alternative for those patients thought to be at increased risk for general anesthesia. Bradycardia during balloon inflation and femoral pseudoaneurysm formation are potential complications unique to angioplasty and stenting. Stenting is not associated with cranial nerve injury, and it therefore may be a more appropriate option for patients with a prior nerve injury, neck irradiation, radical neck dissection, permanent tracheostomy, limited cervical spine mobility, or other conditions that might predispose to a difficult dissection.

Although some centers have suggested that short-term morbidity and mortality events for CAS are comparable to redo CEA, the long-term durability of this procedure remains unknown. Traditionally, carotid stenting has not been employed for late carotid restenosis where recurrent atherosclerotic disease is the most common etiology, or for lesions with ulcerations, free-floating thrombus, or tortuous arterial anatomy. The use of embolic protection devices including filters or retrograde flow systems may help to reduce the stroke risk during carotid stenting, but the benefit has yet to be definitively established in randomized trials. It remains to be seen whether the emergence of carotid protection devices will expand the application of endovascular management to include these lesions with greater risk for embolic complications.

At present, data from outcome studies do not favor one particular operative approach over another as patients with postendarterectomy restenosis exhibit increased risk of adverse events regardless of which procedure is used. The general agreement has been that carotid stenting should be considered for patients with early restenosis whose risk for redo CEA or other open repair is unacceptably high. In the absence of any prospective randomized and controlled trials, the management of patients with recurrent stenosis remains difficult, and the choice of reintervention should be individualized to the patient’s personal risk factors.

Case Continued

The patient is informed of the two different approaches available. Complications that are discussed for surgery include stroke, myocardial infarction, cranial nerve injury, bleeding, infection, and death. Complications related to stenting include access site issues such as bleeding, leg ischemia, and pseudoaneurysm formation. A 4% risk of stroke is balance against the lower risk of postprocedure MI and cranial nerve injury. The patient chooses carotid stenting.

Surgical Approach

Carotid Artery Stenting

Carotid stenting should be performed under local anesthesia. Intravenous sedation should be minimized because it may interfere with intraoperative neurologic assessment. Femoral access is most commonly employed. Balloon inflation during angioplasty is sometimes associated with symptomatic bradycardia that may seldom require transvenous pacemaker placement.

With carotid stent procedures, placement and passage of filters or wires across a lesion can be challenging, particularly when there is tortuosity of the internal carotid artery. The use of stiffer accompanying wires can help straighten the artery to facilitate access. Vessel manipulation may induce vasospasm complicating further instrumentation. Pre-stent dilation of a stenotic area can lead to hemodynamic instability such as bradycardia and hypotension, requiring close anesthesia monitoring and administration of atropine. It is important that a post–stent placement arteriogram is obtained to examine for appropriate placement and flow beyond the carotid bifurcation (Table 1).

TABLE 1. CAS