CHAPTER 90 Re-do Coronary Artery Bypass Surgery

Reoperations present coronary surgeons with their greatest challenges. Patients undergoing reoperation for bypass grafting are different from those who undergo primary surgery. In addition to the risks of a repeated median sternotomy, their coronary artery and noncardiac atherosclerosis is more advanced, noncardiac comorbidities are more common, ventricular function is more likely to be abnormal, and the vascular pathologic processes that jeopardize myocardium are distinct and varied.1–4 All of these issues present specific technical challenges.

In addition to the technical difficulties reoperations present, decision-making is not perfectly straightforward. No major randomized trials have studied patients with prior bypass surgery. In only a few situations do observational studies indicate that reoperative coronary surgery improves prognosis.5 For many patients, percutaneous intervention is an appealing prospect, but unfortunately the results of percutaneous treatment of patients with prior surgery have been suboptimal even in the era of drug-coated stents.6–8

The pathologic changes of vein grafts are important, not only as causes of reoperations but also as causes of events associated with medical or interventional treatment.9,10 Early vein graft occlusion is usually associated with intimal disruption and thrombosis. Within 2 to 3 months of surgery, a proliferative intimal fibroplasia develops in most vein grafts. This is a concentric, diffuse, and cellular lesion that becomes more fibrous with time. It usually does not cause stenosis or occlusion. Within a few years of operation, lipid deposition may occur in association with intimal fibroplasia; the resulting lesion is termed vein graft atherosclerosis. The fully developed lesion of vein graft atherosclerosis is very different from native vessel atherosclerosis. Vein graft atherosclerosis is superficial, nonencapsulated, diffuse, and concentric. It is an extremely friable lesion and is much more prone to embolization than is native vessel atherosclerosis. In addition, clinical studies appear to show that it is more consistently progressive than is true of native vessel atherosclerosis as vein graft stenoses caused by vein graft atherosclerosis predict a high level of clinical events. Patients with coronary risk factors such as hyperlipidemia and diabetes appeared to experience an increased incidence of vein graft atherosclerosis and graft failure.11 There is now evidence that treatment with platelet inhibitors and statins decreases the rate of late vein graft failure. However, even with these measures, vein graft atherosclerosis has not been eliminated.

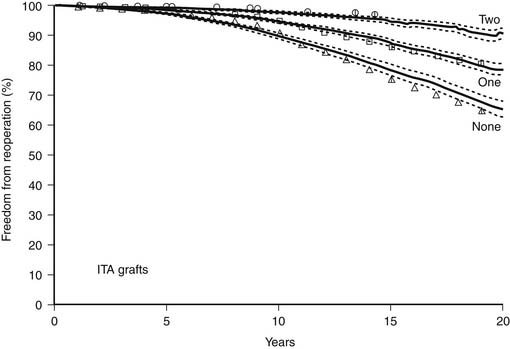

ITA grafts rarely develop atherosclerosis, and the patency rate of ITA grafts, particularly to the LAD coronary artery, exceeds that of vein grafts.11 The use of ITA to LAD grafts at primary operations clearly decreases the risk of reoperation during the first 10 postoperative years, and the use of both ITA grafts further decreases the risk of reoperation (Fig. 90-1).4,12,13 Furthermore, although patent ITA grafts present technical challenges at reoperation, atherosclerotic embolization is not a risk as it is for patients with patent but atherosclerotic vein grafts.

For patients undergoing primary bypass surgery, the likelihood of undergoing a reoperation will depend on the length of their life, the severity of the atherogenic diathesis and the effectiveness of the treatment of that diathesis, the details of the primary operation, the alternative therapies available, and the physician’s and patient’s preferences. Review of patients undergoing primary bypass surgery at the Cleveland Clinic in the 1971-1974 time frame documented a 25% chance of reoperation by 20 postoperative years.14 Today we would expect that figure to be much less as the number of isolated coronary reoperations performed has declined. The Society of Thoracic Surgeons database noted 16,091 isolated coronary reoperations reported in 1998 compared with 9587 in 2007.15

INDICATIONS FOR CORONARY REOPERATIONS

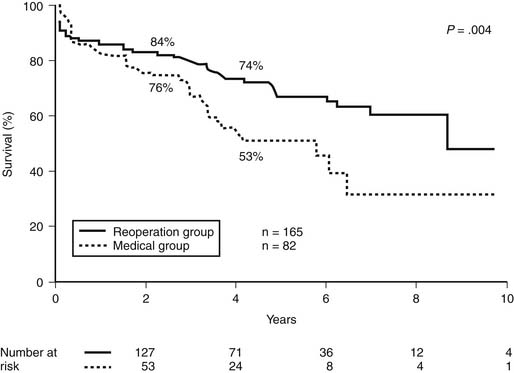

As has been true of patients undergoing primary bypass surgery, functional studies may add to the accuracy of identifying those patients likely to have unfavorable outcomes without reoperation. Patients who demonstrate ischemia and an impaired exercise capacity are at more risk for death and cardiac events without reoperation than are those with negative or only mildly positive stress test results.16

SUMMARY OF CURRENT INDICATIONS FOR TREATMENT OF PATIENTS WITH PREVIOUS BYPASS SURGERY

In the absence of contraindications, all patients with previous bypass surgery should be treated with platelet inhibitors, statin-type drugs, and control of risk factors including hypertension, diabetes, and hyperlipidemia. The indications for more invasive treatment are related to symptom relief and, in some circumstances, improvement of prognosis.

The availability of percutaneous coronary treatments can be an advantage in the symptomatic treatment of patients with previous bypass surgery. Native vessel disease in particular, when accessible, can be effectively treated with stenting, and in the current era of drug-coated stents, it is often effective. The treatment of vein graft disease with percutaneous intervention has, unfortunately, not been effective in the long term even with the use of drug-coated stents.8,17–19 However, despite those issues, it is still reasonable to use stenting for treatment of symptomatic vein graft disease when large amounts of myocardium are not jeopardized and symptom relief is the goal. There is no evidence that the treatment of vein graft disease with percutaneous treatment achieves any improvement in prognosis in any situation.

TECHNICAL ASPECTS OF CORONARY REOPERATIONS

Reoperations are more difficult than primary operations. Some of that difficulty relates to similar but more extreme pathologic processes that are encountered at reoperation, whereas some problems are unique to reoperations. Potential technical problems during coronary reoperations include sternal reentry, aortic atherosclerosis, atherosclerotic vein grafts, patent arterial bypass grafts, diffuse native coronary artery disease, lack of bypass conduits, locating coronary arteries, and myocardial protection. The most common cause of in-hospital death after coronary reoperation is perioperative myocardial infarction. Those myocardial infarctions are often anatomically based; their causes include injury to bypass grafts, atherosclerotic embolization from vein grafts or from the aorta, myocardial devascularization after graft removal, hypoperfusion through new grafts, incomplete revascularization, early graft occlusion, air embolization, technical error, and inadequate myocardial protection. The planning for reoperation and the intraoperative conduct of the procedure must be designed to avoid these anatomic causes of perioperative myocardial infarction.