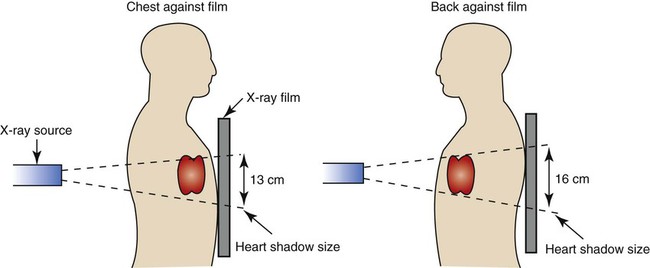

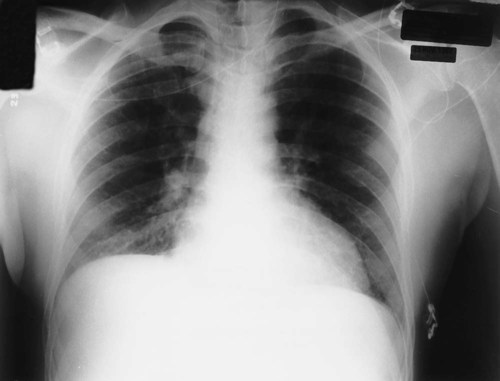

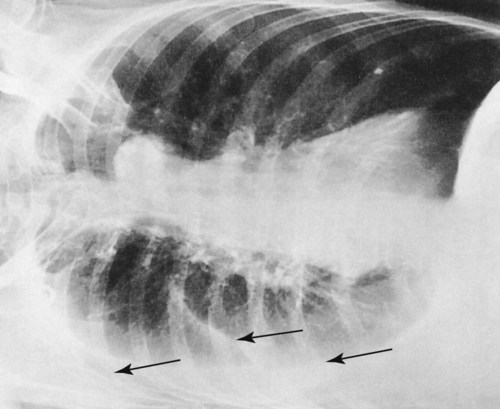

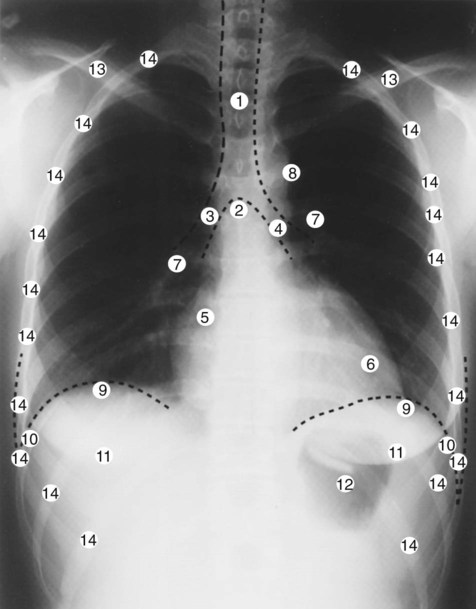

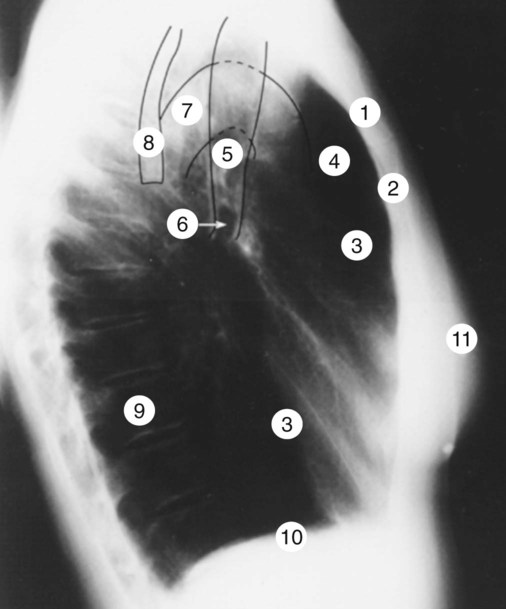

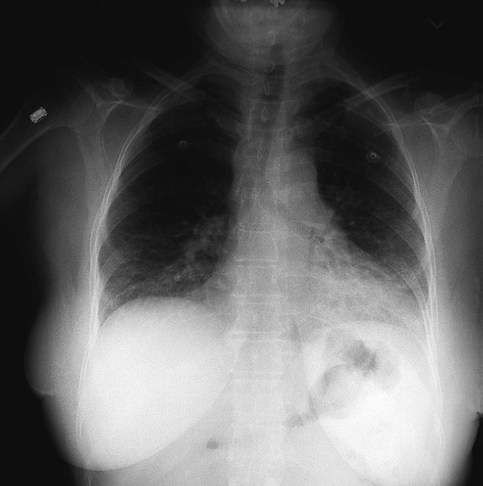

After reading this chapter, you will be able to: • Describe the fundamentals of radiography. • Differentiate among the following standard positions and techniques of chest radiography: • Lateral decubitus radiograph • Define the following radiologic terms commonly used during inspection of the chest radiograph: • Describe the three steps to evaluate technical quality of the radiograph. • Describe the sequence of examination, and include the following: • Describe the diagnostic values of the following radiologic procedures: • Positron emission tomography (PET) • Positron emission tomography and computed tomography scan (PET/CT scan) • Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) • Define key terms and complete self-assessment questions at the end of the chapter and on Evolve. The x-ray examination is usually performed with the patient’s lungs in full inspiration to show the lung fields and related structures to their greatest possible extent. At full inspiration the diaphragm is lowered to approximately the level of the ninth to eleventh ribs posteriorly (Figure 7-1). For certain clinical conditions, radiographs are sometimes taken at the end of both inspiration and expiration. For example, in patients with obstructive lung disease an expiratory radiograph may be made to evaluate diaphragmatic excursion and the symmetry or asymmetry of such excursion (Figure 7-2). Compared with the PA radiograph, the AP radiograph has a number of disadvantages. For example, the heart and superior portion of the mediastinum are significantly magnified in the AP radiograph. This is because the heart is positioned in front of the thorax as the x-ray beams pass through the chest in the anterior-to-posterior direction, causing the image of the heart to be enlarged (Figure 7-3). The AP radiograph also often has less resolution and more distortion. Because the patient is often unable to sustain a maximal inspiration, the lower lung lobes frequently appear hazy, erroneously suggesting pulmonary congestion or pleural effusion. Finally, because the AP radiograph is often taken in the intensive care unit, extraneous shadows, such as those produced by ventilator tubing and indwelling lines, are often present (Figure 7-4). To view the right lung and heart, the patient’s right side is placed against the cassette. To view the left lung and heart, the patient’s left side is placed against the cassette. Therefore a right lateral radiograph would be selected to view a density or lesion that is known to be in the right lung. If neither lung is of particular interest, a left lateral radiograph is usually selected to reduce the magnification of the heart. The lateral radiograph provides a view of the structures behind the heart and diaphragmatic dome. It also can be combined with the PA radiograph to give the respiratory care provider a three-dimensional view of the structures or of any abnormal densities (Figure 7-5). The lateral decubitus radiograph is useful in the diagnosis of a suspected or known fluid accumulation in the pleural space (pleural effusion) that is not easily seen in the PA radiograph. A pleural effusion, which is usually more thinly spread out over the diaphragm in the upright position, collects in the gravity-dependent areas while the patient is in the lateral decubitus position, allowing the fluid to be more readily seen (Figure 7-6). Before the respiratory care practitioner can effectively identify abnormalities on a chest radiograph, he or she must be able to recognize the normal anatomic structures. Figure 7-7 represents a normal PA chest radiograph with identification of important anatomic landmarks. Figure 7-8 labels the anatomic structures seen on a lateral chest radiograph.

Radiologic Examination of the Chest

Standard Positions and Techniques of Chest Radiography

Posteroanterior Radiograph

Anteroposterior Radiograph

Lateral Radiograph

Lateral Decubitus Radiograph

Inspecting the Chest Radiograph

![]()

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree

Thoracic Key

Fastest Thoracic Insight Engine

-inch square is fixed to the end of the rotating anode at the center of the tube. This tungsten block is called the target. Tungsten is an effective target metal because of its high melting point, which can withstand the extreme heat to which it is subjected, and because of its high atomic number, which makes it more effective in the production of x-rays.

-inch square is fixed to the end of the rotating anode at the center of the tube. This tungsten block is called the target. Tungsten is an effective target metal because of its high melting point, which can withstand the extreme heat to which it is subjected, and because of its high atomic number, which makes it more effective in the production of x-rays.