PVOD with Claudication (SFA Stent)

GEORGE H. MEIER

Presentation

A 67-year-old male smoker presents to your office for evaluation of increasing pain in the right calf with walking. This was gradual in onset, beginning about 4 months ago, but has not resolved and continues to limit his daily activities. Initially, he thought that he had injured himself playing softball, but the pain has persisted. The “tightness” in his right calf is worse when he climbs stairs or when he is in a hurry. If he stops and stands in place, the discomfort resolves in a few minutes and he can resume walking. He has no other symptoms but does have a past history of hypertension and rare exertional chest pain. His examination demonstrates normal pulses in the left lower extremity with only a femoral pulse on the right side. He has no ulcerations or skin changes, and there is no dependent rubor.

Differential Diagnosis

Any symptom of exertional discomfort in the leg carries with it a differential diagnosis of not only peripheral arterial disease (PAD) but also musculoskeletal injury and lumbar radiculopathy. Smoking not only increases the risk of PAD but also increases the risk of lumbar disc disease. Neurogenic pseudoclaudication is a common diagnosis in this population and would be high in the differential diagnosis.

Generally, workup of the lumbar spine for causes of lower extremity pain is unwarranted unless lower back symptoms predominate. If necessary, plain x-rays of the lumbar spine, spinal CT, and spinal MRA all have some utility in this population. For most patients, plain x-rays of the lumbar spine are sufficient prior to any consideration of referral for evaluation for disc disease or bony impingement syndromes.

Rarer diagnoses are sometimes seen in younger patients due to muscular entrapment of the popliteal artery. In these settings, exertional pain in the calf may occur without atherosclerosis. If this is suspected, axial MRA can be performed and will demonstrate medial deviation of the popliteal artery around the muscles of the calf. Most commonly, the popliteal artery is medial to the medial head of the gastrocnemius muscle, leading to compression of the artery with tightening of the calf muscles.

Workup

The evaluation really begins with the physical examination. Most of the decisions concerning diagnostic testing start with an evaluation of the femoral pulses. If the femoral pulse to the symptomatic extremity is normal, then the occlusive arterial disease is likely confined to the infrainguinal vessels. If the femoral pulse is abnormal, then evaluation of the abdominal aorta and iliac vessels will also be needed.

Initial evaluation for exertional lower extremity symptoms, particularly with an abnormal pulse examination, should include baseline arterial noninvasive vascular testing. While most patients require only an ankle-brachial index to document the presence of significant vascular disease, a minority will require treadmill exercise testing with ankle-brachial index (ABI) measured before and after exercise. These patients may have normal circulation at rest but have a significant decrement in pulses and ABI under the stress of exercise.

With inflow disease, CTA is useful in the differential diagnosis of lower extremity claudication. Most commonly, this is in the setting of abnormal inflow to the lower extremity as represented by an abnormal femoral pulse. CTA provides anatomic information about the aorta and iliac vessels that can be used to then plan subsequent management. Alternatively, duplex ultrasound mapping of the aorta and iliac vessels can be performed to limit dye and radiation exposure.

Ultimately, the diagnostic test of choice will be an abdominal aortogram with bilateral runoff arteriography (Figs. 1 and 2). Whether this is done at the same time as an intervention, or at a separate setting, is up to the discretion of the interventionalist in conjunction with the patient’s wishes.

FIGURE 1 Right superficial femoral artery occlusion.

FIGURE 2 Reconstitution of the above-knee popliteal artery in the same patient.

Diagnosis and Treatment

With this history, the leading diagnosis is intermittent claudication due to arterial vascular insufficiency. Since the most common risk factor for claudication remains cigarette smoking, initial management is smoking cessation, risk factor modification, and an exercise program of daily walking.

Risk factors for PAD include smoking, diabetes, hyperlipidemia, and a sedentary lifestyle. For this reason, the above initial management is generally appropriate. Goal for diabetic control is generally an HgbA1C of less than 7%. Medically, all patients should be started on low-dose aspirin and a statin, both of which have a benefit relative to coronary events. While hypertension is a significant cardiac risk factor, hypertension is at most a minor risk factor for PAD. Control of hypertension is important nonetheless for lowering risk of a cardiac event.

Most atherosclerotic vascular disease is a systemic process, with coronary and cerebral involvement the norm. Since atherosclerosis is generally progressive over time, most treatment is initially focused on temporizing and controlling the symptoms. A daily walking program is effective at increasing exercise tolerance and decreasing leg symptoms. Generally, the disease remains stable for many years before progression may occur. In those patients with an ABI below 0.5, the risk of intervention is sufficiently high so that this should be discussed with the patient at that time in most cases.

While some medical therapies can alter the severity of PAD symptoms, it is unclear when these should be applied. Pentoxifylline has been used for many years but has only a modest benefit in patients with vasculogenic claudication. More appropriately, cilostazol seems to better improve walking ability but is generally contraindicated in patients with heart failure. Finally, ramipril, an ACE inhibitor, has been shown to improve walking distance in patients with PAD and may be an appropriate drug to consider in a PAD patient with hypertension.

Interventional Approach

The fundamental issue in the treatment of lower extremity claudication is the differentiation of inflow disease from outflow disease. Initial diagnostic arteriography including the abdominal aortic and iliac systems is essential to defining any abnormalities in the inflow arteries. If any aorta or iliac abnormalities are present, treatment of these issues should precede any treatment of outflow disease. Typically, open or endovascular treatment of iliac disease also tends to be more durable than treatment of lower extremity disease.

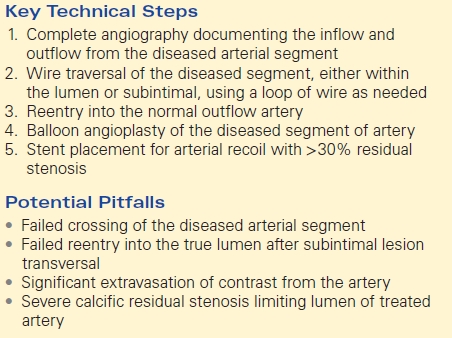

One of the challenges of performing diagnostic testing at the time of possible treatment is the need for immediate decision making during the procedure. If extensive inflow atherosclerosis is seen in the aorta, then this may necessitate open surgery. Iliac disease on the other hand usually requires endovascular treatment either prior to superficial femoral artery intervention or at the same time. In some cases, the presence of significant disease in the common femoral artery may require open intervention either at the time of the endovascular procedure (hybrid approach) or preceding endovascular treatment. If at any point the decision making is uncertain, delaying the intervention for further discussion or evaluation is warranted (Table 1).

TABLE 1. Endovascular SFA Treatment