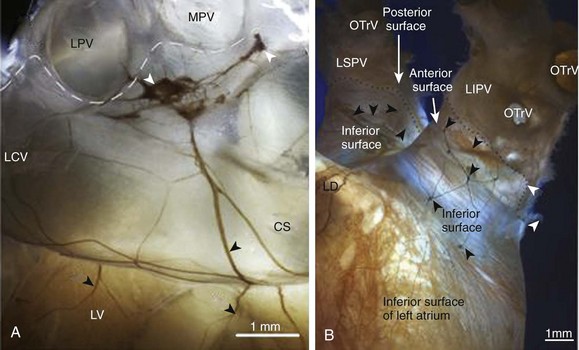

39 The traditional view of the sympathetic and parasympathetic branches of the autonomic nervous system is that they exert fine-tuned reciprocal influences on the heart. Sympathetic stimulation increases heart rate, electrical conductivity, and contractility, whereas in general, parasympathetic stimulation produces opposing inhibitory effects. However, the cardiac regulation driven by the two branches of the autonomic nervous system is complex. In fact, the electromechanical function of the heart is subject to the influence of not one, but two separate autonomic nervous systems—one extrinsic and the other intrinsic. In the extrinsic system, the primary site for regulating sympathetic and parasympathetic (vagal) outflow to the heart and blood vessels is the medulla, which is located in the brainstem above the spinal cord. The intrinsic cardiac nervous system (ICNS) is composed of ganglionated plexi distributed at various locations within the heart, including the epicardium, myocardium and endocardium.1 Efferent fibers of extrinsic autonomic system enter the heart through the hilum and then connect with and modulate the activity of the intrinsic cardiac ganglionated plexi. Both systems are susceptible to neuromodulatory influences from various inputs, including the central nervous system, the baroreceptor and chemoreceptor reflexes, and the local interneuronal interactions within the heart itself.2 Efferent preganglionic parasympathetic innervation originates mainly in the nucleus ambiguous of the medulla, whereas some neurons are located in the dorsal motor nucleus and the regions between these two nuclei. Neurons originating in these areas project their axons to form synapses with postganglionic neurons located throughout the various atrial or ventricular ganglionated plexi.2 On the other hand, sympathetic innervation originates in the interomediolateral nucleus of spinal cord and segments C1-C3, C7-C8, and T1-T4,3 where preganglionic axons advance to form synapses with the sympathetic postganglionic neurons of the intrathoracic ganglia (left and right stellate ganglia, cranial thoracic sympathetic chain ganglia, middle and superior cervical ganglia and mediastinal ganglia) and the intrinsic cardiac ganglia.4 In addition to this efferent component, the extrinsic nervous system contains afferent neurons that transmit mechanosensitive and chemosensitive information from the local environment of several cardiac regions, coronary vasculature, and the major intrathoracic and cervical vessels.5 Initially, the ICNS was thought to be composed of parasympathetic postganglionic neurons and their axonal projections, alongside with intramyocardial chromaffin cells, which act as a simple relay region under the control of the central nervous system. However, more recent studies have shown that the ICNS represents the final relay center for the coordination of regional cardiac function and is composed of sensory (afferent), interconnecting (local circuit), and motor (adrenergic an cholinergic efferent) neurons. These neurons communicate with intrathoracic extracardiac ganglia, forming a distributive network that processes centripetal and centrifugal neuronal impulses for cardiac control, under the influence of the central nervous system, and circulating catecholamines.2 The number of cardiac ganglia is variable and species dependent.6 The location, shape, and size are also variable, but in many mammals, including humans, intrinsic cardiac ganglia are usually distributed at specific atrial regions: around the sinoatrial node (SAN), the roots of caval and pulmonary veins (PVs), and near the atrioventricular node.7,8 Intrinsic cardiac ganglia are also present within the ventricles, although in a smaller number compared with the atria.9 The ICNS regulates several aspects of cardiac function such as heart rate, atrial and ventricular refractoriness, conduction, contractility and blood flow.10 Furthermore, the ICNS modulates intrathoracic and central cardiovascular-cardiac reflexes and coordinates parasympathetic and sympathetic efferent postganglionic neuronal input to the heart.11 It has been suggested that intrinsic cardiac ganglionated plexuses exert influence over adjacent myocardial regions,12–14 where vagal deceleration of heart rate can be mediated selectively by neurons located at the junction of the right atrium and superior vena cava, whereas the effects on atrioventricular nodal transmission can be controlled by the neurons of a fat pad at the junction of the inferior vena cava and the inferior left atrium.13 On the other hand, Armour2 proposed that intrinsic cardiac ganglia in atrial or ventricular ganglionated plexuses can selectively influence the electrical and mechanical properties in adjacent tissues and cardiac chambers. For example, it has been reported that the cholinergic neurons of the right atrial ganglionated plexuses can decrease the rate of discharge of SAN, depress the atrioventricular node conduction, and affect ventricular contractility.15 In addition, the repolarization of ventricular muscle can be influenced by atrial and ventricular ganglia.16 Parasympathetic stimulation produces negative chronotropic effects mediated by the release of acetylcholine (ACh) from parasympathetic postganglionic neurons, launching a second messenger signaling cascade resulting in the modification of ion channels activities, negative regulation of cAMP production, and positive regulation of cAMP hydrolysis.17 The neurotransmitter ACh binds to the muscarinic receptor M2 and activates the inhibitory G-protein, whose αi subunit inhibits adenylyl cyclase activity, reduces intracellular cAMP levels and protein kinase A (PKA) activity, and produces an overall decrease of the funny current (If) and the L-type calcium current (ICa-L).18,19 However, the βγ-subunit directly activates the ACh-sensitive inward-rectifier potassium current (IKACh). In pacemaker cells, the integration of these effects leads to a relatively more hyperpolarized maximal diastolic potential, slower phase 4 depolarization, and smaller action potential amplitude, producing a decrease in the rate of discharge of the SAN.17 Conversely, sympathetic stimulation increases the SAN rate of discharge via activation of β-adrenergic receptors, enhancing the activity of several ion channels as well as intracellular calcium release and cycling.17 Activation of β1 receptors stimulates adenylyl cyclase activity and results in an increase in intracellular cAMP concentration, activating PKA, which phosphorylates membrane proteins and enhances ICa-L, If, the slow and rapid delayed rectifier currents (IKs, and IKr), and the sodium calcium exchange current.20–23 Collectively, these effects increase the pacemaker cell’s action potential upstroke velocity, decrease the action potential duration, increase the slope of diastolic depolarization, and consequently increase the SAN activation rate.24 The pulmonary vein ganglia (PVG) are located at the roots of the pulmonary veins and form a circuit via interconnecting nerve fibers (Figure 39-1). They have received special attention because they might have a role in promoting pathophysiological conditions such as atrial fibrillation (AF).26 Figure 39-1 Neuroanatomical characterization of pulmonary veins (PVs) whole-mount preparations. A, A macrophotograph illustrating the neuroanatomy of the left dorsal neural subplexus at the base of the PVs in a mouse heart stained histochemically for acetylcholinesterase. White arrowheads point to the intrinsic cardiac ganglia, and black arrowheads indicate topographically comparable nerves at the coronary sinus. Dashed lines demarcate limits of the heart hilum. B, A macrophotograph of the inferior surface of human embryonic left PVs showing the course of epicardial ganglionated nerves (extending from the middle and left dorsal neural subplexi to the PV roots). Dotted line indicates limits of the cardiac hilum; black arrowheads indicate epicardial ganglia. CS, coronary sinus; LCV, left cranial (left azygos) vein; LPV, left pulmonary vein; LV, left ventricle; MPV, middle pulmonary vein; LD, left dorsal subplexus; LIPV, left inferior pulmonary vein; LSPV, left superior pulmonary vein; OTrV, orifice of tributaries of the pulmonary vein. (Modified from Rysevaite K, Saburkina I, Pauziene N, et al: Morphologic pattern of the intrinsic ganglionated nerve plexus in mouse heart. Heart Rhythm 8:448–454, 2011.) Recent studies have focused on the macroscopic and microscopic neuroanatomy of the PVs and have provided detailed descriptions of nerve distribution and characteristics. Chevalier et al27 found that, in human hearts, nerve fibers and ganglia have distinct distribution patterns in the PVs, with a higher nerve density at the ostia compared with the distal PVs, and are more abundant epicardially, rather than endocardially. In addition, Tan et al28 performed immunostaining of 192 PV-atrial segments from eight human hearts using anti–tyrosine hydroxylase and anti–choline acetyltransferase antibodies to label adrenergic and cholinergic elements, respectively. They found a similar d noted adrenergic and cholinergic immunofluorescence colocalization in approximately 90% of ganglia. A significant proportion of ganglia (30%) expressed both tyrosine hydroxylase–positive and choline acetyltransferase–positive cells simultaneously. More recently, Vaitkevicius et al29 investigated in detail the characteristics and distribution of the neural routes by which autonomic nerves supply the human PVs in 35 intact (nonsectioned) left atrial-PV complexes stained with the Karnovsky–Roots acetylcholinesterase precipitation reaction. They found that three epicardial subplexi located at the inferior portion of PVs are the sole source of nerve supply (nerves extend to the PVs from the cardiac ganglionated plexus only), whereas free sensory nerve endings aggregate subendothelially. Based on the correlation between the areas of epicardial ganglia and the number of somas they contain, it was estimated that approximately 8000 intrinsic nerve cells (2000 associated with each PV) contribute to the neural control of PVs in humans.29 Nerve fibers originating from PVG can extend to different regions of the heart. Puodziukynas et al.30 examined in sheep, the long-term effects of radiofrequency ablation of PVG on the structure of epicardial nerves located distally from the ablation sites. Ablation of PVG resulted in the degeneration of remote epicardial nerves after 2 to 3 months. There was disorganization in the neural structures of the dorsal left atrium, coronary sinus, ventricle, and atrioventricular node. These experiments suggested that there could be anatomical links between the PVG and areas distal to the PVs surrounding. Based on that information, mouse whole-mount atrial preparations31 were used to show that PVG form a circuit via interconnecting nerve fibers. Most important, nerves emerged from the PV ganglionic circuit and advanced toward the SAN area and innervate it. The data demonstrated that there was a direct neuroanatomical communication between the PVG and the SAN. It is well known that the SAN can be regulated by intrinsic ganglia located in its vicinity, and this regulation has been assumed to be parasympathetic.10,32–34 Indeed, experimental studies have shown that ganglia of the fat pad located near the right superior pulmonary vein, at the junction of the right atrium and superior vena cava (right atrial ganglionated plexus [RAGP]), mediate a selective negative chronotropic effect.35 Similarly, the posterior atrial ganglia (found in a fat pad on the rostral surface of the right atrium) have a modest role in producing vagal bradycardia,33 but can mediate more pronounced parasympathetic effects.36,37 A third fat pad located between the medial superior vena cava and aortic root appears to be the “head station” of vagal fibers that project to both atria.38

Pulmonary Vein Ganglia and the Neural Regulation of the Heart Rate

Autonomic Innervation of the Heart

Extrinsic Nervous System

Intrinsic Nervous System

Autonomic Regulation of Pacemaker Activity

Pulmonary Vein Ganglia and Heart Rate Control

Neuroanatomy

Control of Heart Rate

![]()

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree

Pulmonary Vein Ganglia and the Neural Regulation of the Heart Rate