Procedures for Hemodialysis Access Steal Syndrome

Karen J. Ho

Haimanot Wasse

Introduction

Dialysis access-associated steal syndrome (DASS), which is also known as “access-related hand ischemia,” “digital hypoperfusion ischemic syndrome,” and “arterial steal syndrome,” can occur with variable severity in up to 20% of arteriovenous access procedures. The construction of an arteriovenous anastomosis results in decreased perfusion pressure distal to the fistula that can lead to ischemia if compensatory mechanisms are inadequate or there is coexistent underlying arterial occlusive disease in the inflow (e.g., subclavian) or outflow (e.g., ulnar) arteries and/or distal arteriopathy. Risk factors for DASS include age, female gender, diabetes mellitus, coronary artery disease, hypertension, smoking, peripheral arterial occlusive disease, brachial artery-based access procedures, large-caliber conduits, and prior episodes of arterial steal syndrome, but the diagnosis of steal syndrome is largely a clinical one. Treatment goals are to reverse hand ischemia, prevent long-term disability in the hand, and to preserve the access.

DASS can be classified by severity of symptoms, as shown in Table 19.1. The incidence of DASS is highest after brachial artery-based procedures, with approximately half classified as severe. Surgical intervention is generally reserved for patients with disabling symptoms and limb-threatening ischemia, that is, stage 2 to 3. Ischemic symptoms can also occur early (<30 days) or late (>30 days) postoperatively, with most early symptoms resolving with close observation (as collateral circulation augments), while late symptoms tend to be progressive and demand aggressive management.

Table 19.1 Classification of Severity of Arterial Steal Syndrome | ||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

DASS is largely a clinical diagnosis and is generally made on the basis of a simple physical examination of the access and distal extremity (Table 19.1), but can be confirmed by diagnostic testing. The presence of a digital blood pressure <60 mm Hg or a digital to contralateral brachial index <0.45 in a patient with an arteriovenous access is highly associated with hand ischemia.

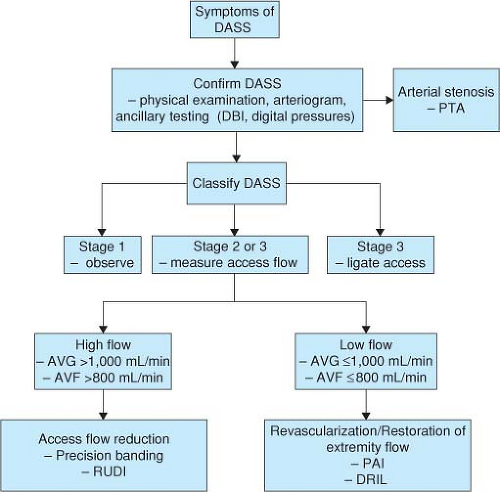

It is important to recognize that DASS can occur in patients with both high or low arteriovenous blood flow and that treatment varies accordingly (Fig. 19.1). As such, critical studies include a duplex ultrasound to determine access blood flow and an arteriogram to identify inflow stenosis. In treating DASS, an arteriovenous blood flow of at least 500 to 600 mL/min must be achieved to maintain access patency and meet hemodialysis machine blood pump requirements.

Table 19.2 Treatment Options for Arterial Steal Syndrome | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Treatment options for DASS are shown in Table 19.2 and are described in greater detail below.

Access Ligation

Although the goals of treating a patient with DASS are both to relieve ischemia and to preserve the access, these are not always possible. Access ligation eliminates the hemodynamic changes associated with the arteriovenous access, but the obvious disadvantage is loss of access. Notably, patients who develop DASS are at risk for recurrence with subsequent attempts at access placement, which limits the option of simply ligating an access and placing a new one on the contralateral extremity. However, access ligation may be most appropriate for patients with comorbidities that preclude a more extensive revascularization attempt, have failed other attempts at revascularization, have limited conduit for a distal revascularization with interval ligation (DRIL) or revision using the distal inflow (RUDI) procedure, or have extensive tissue loss. Access ligation is also indicated when other procedures are not suitable or effective in relieving ischemia, in order to minimize tissue loss and disability.

Correction of Arterial Inflow Stenosis

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree