Primary Seminomas of the Mediastinum

David C. Rice

Cesar A. Moran

Robert J. Dabal

Douglas E. Wood

Extragonadal germ cell tumors (EGCTs) are rare and account for only 1% to 5% of all germ cell tumors.22 EGCTs tend to arise in the midline of the body, in particular in the central nervous system (pineal gland), the retroperitoneum, and the mediastinum.28,29 Mediastinal EGCTs account for 10% to 15% of all mediastinal tumors in adults. The histologic classification of mediastinal GCTs, although similar to that used for gonadal tumors, has been modified slightly, mainly with respect to teratomatous lesions,24 while other terms have been maintained, namely seminoma (pure), yolk sac tumor (endodermal sinus tumor), embryonal carcinoma, choriocarcinoma, and combined GCT (see below). Mediastinal seminomas were initially described by Woolner and associates in 195533 and account for 15% to 37%1,24 of all mediastinal GCTs, being second only to teratomas in terms of frequency.

Etiology

Although the histogenesis of mediastinal seminomas remains unknown, several theories have been commonly espoused. Frideman7 was the first to propose that all GCTs originate from extragonadal, potentially biphasic GCTs left within the embryonic thymus. This theory was further endorsed by Lattes18 in 1962. A second, more recent theory espoused by Frideman8 holds that germ cells are present in ectopic sites other than the thymus in all healthy persons as part of a wide distribution during normal embryogenesis or as part of misplacement during migration along the midline from the yolk sac to the embryonal gonadal ridge. A third but largely discounted theory holds that mediastinal sites of GCTs merely represent metastatic lesions from a gonadal primary site that is occult and that these are not primary lesions. Autopsy series such as that published by Johnson and colleagues12 have basically disproved this theory. In addition, clinical reports of primary mediastinal seminomas occurring in women by Polansky30 and El-Domeiri5 and their associates dispute this theory. The occurrence of mediastinal seminomas in women is extremely unusual; this tumor is almost exclusively found in men. In the largest series of mediastinal GCTs yet reported, only a few tumors were present in women, and those were teratomatous lesions.24

Pathology

Although the classification of mediastinal GCTs has followed the conventional classification of gonadal GCTs, a more novel classification of mediastinal GCTs has been proposed.24 This classification provides a better assessment of the different components that may be present in a particular tumor, particularly with respect to teratomatous lesions.

Classification of Mediastinal Germ Cell Tumors

Mature teratoma

Immature teratoma

Teratomas with malignant component:

Type I: with an associated GCT (seminoma, etc.)

Type II: with another epithelial malignancy (squamous, adenocarcinoma, etc.)

Type III: with sarcomatous component (rhabdomyosarcoma, osteosarcoma, etc.)

Type IV: a combination of any of the above

Seminoma

Yolk sac tumor (endodermal sinus tumor)

Embryonal carcinoma

Choriocarcinoma

Combined GCT without teratomatous component

Gross Features

Mediastinal seminomas are typically slow-growing tumors that present as large mediastinal masses with a lobulated appearance, including areas of necrosis, hemorrhage, or both (Fig. 193-1). The average size of these tumors at presentation is 5 cm, although many have been as large as 14 cm, as noted by Martini20 and Schantz31 and their associates. The tumors are well circumscribed but not encapsulated. At cut surface, they are lobulated, with a smooth surface. Calcification is infrequently seen. Rarely, the tumor may present as a cystic structure, as reported by Kataoka and Seno13; in a few cases the tumor mass may mimic multilocular thymic cyst.25 However, cystic seminomas represent only 5% of al mediastinal seminomas.

Histologic Features

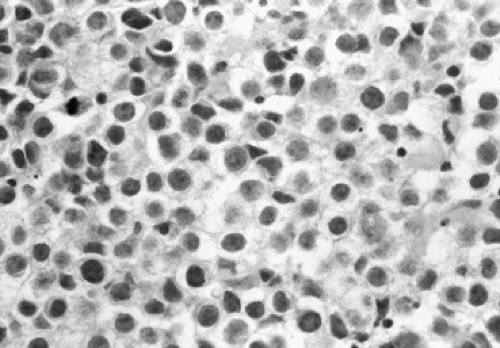

The microscopic features of mediastinal seminomas are similar to those seen in the gonads. At low magnification, the tumor is characterized by sheets of neoplastic cells that may adopt a discrete nesting pattern. The malignant cells, which are round or polygonal, are medium to large (15 to 30 microns), with indistinct cell borders, lightly eosinophilic cytoplasm, and round or oval nuclei with prominent nucleoli (Fig. 193-2). Delicate connective tissue septa typically separate the sheets or lobules of cells. An inflammatory reaction composed predominantly of lymphocytes is invariably present either in the fibroconnective tissue or admixed with neoplastic cells. Necrosis, hemorrhage, and increased mitotic activity are not common in mediastinal seminomas. In a study of 120 cases,23 the authors found other features, including lymphoid hyperplasia, granulomatous reaction, and the presence of syncitiothrophoblastic cells.

Because seminomas may be associated with another malignancy (usually another GCT or a sarcoma), it is important to sample these tumors properly to identify nonseminomatous components. In addition, the use of serum markers like alpha-fetoprotein (AFP) may be helpful in suggesting the possibility of a mixed GCT.

Immunohistochemical Features

Immunohistochemical staining of mediastinal seminomas reveals results that correspond to known serum expression of tumor markers. These tumors typically express high levels of placental alkaline phosphatase (PLAP), rarely express human chorionic gonadotropin (HCG), and do not express AFP. Of note, Moran and associates23 reported that focal dot-like positive results for CAM 5.2 low-molecular-weight keratins occur in 75% of these tumors. Of interest, only 20% of testicular seminomas were positive for CAM 5.2 low-molecular-weight keratin, according to Suster and associates.32 Focal cytoplasmic staining for wide-spectrum keratin is present 70% of the time, and positive staining for vimentin occurs in 70% of cases. More recently it has been reported that seminomas also react with CD-117.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree