Primary Lung Tumors Other than Bronchogenic Carcinoma: Benign and Malignant

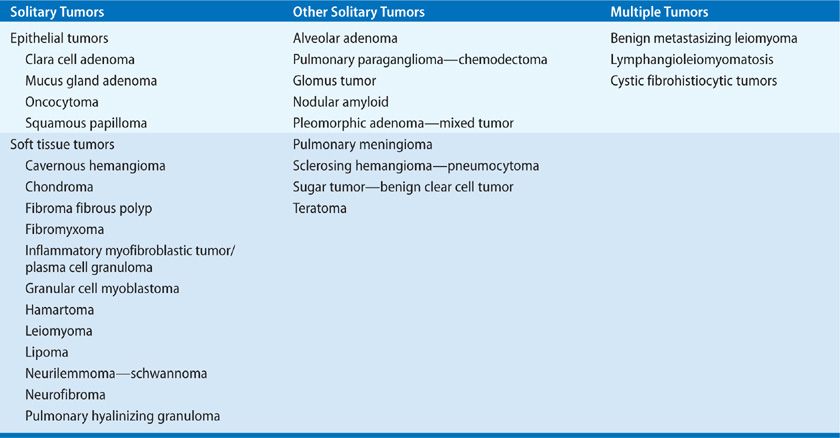

Bronchogenic carcinoma represents the overwhelming majority of pulmonary neoplasms. However, a great variety of tumors originate in the lung.1 Benign neoplasms (Table 117-1) comprise less than 1% of all resected lung tumors and nonbronchogenic primary pulmonary malignancies (Table 117-2) account for 3% to 5% of all lung tumors. Numerous classifications of these rare tumors have been devised, though none are widely accepted. Due to the disparate histogenesis of these varied tumors, it is best to discuss them individually.

BENIGN TUMORS

A broad array of benign primary lung tumors has been recognized, as discussed below.

MUCUS GLAND ADENOMA

MUCUS GLAND ADENOMA

Mucus gland adenoma, also known as bronchial cystadenoma, is a benign epithelial tumor that originates in the bronchial submucus glands and presents as an exophytic endobronchial mass.2 Mucus gland adenoma occurs in adults and children and has no gender predilection.3 The tumor occurs in the segmental or lobar bronchi and symptoms are due to obstruction or hemorrhage. Histologically, mucus-filled acini are lined with well-differentiated mucus-secreting cells, without any evidence of invasion. Radiographically, mucus gland adenomas appear as coin lesions on chest radiograph, or with an “air-meniscus” sign on CT scan. Treatment is endoscopic local excision. However, lobectomy may be required if the distal lung is destroyed.

SQUAMOUS PAPILLOMA

SQUAMOUS PAPILLOMA

Tracheal papillomatosis, a form of recurrent respiratory papillomatosis (RRP), occurs in both children and adults.4 When symptomatic, patients can present with dyspnea, cough, hemoptysis, and symptoms simulating reactive airway disease.5 Histologically, papillomas consist of stratified squamous epithelium with a fibrovascular core. Imaging studies demonstrate lesions within the trachea and bronchi. Bronchoscopy is the diagnostic modality of choice. Squamous metaplasia and malignant transformation occur in 0.3% to0.5% of patients with RRP and have been linked to radiation exposure, tobacco use, and bleomycin.4 Infection with HPV 11, HPV 16, or HPV 18 rather than HPV 6 is associated with a worse prognosis. Endoscopic excision is the treatment of choice for tumors with malignant transformation or causing airway obstruction.

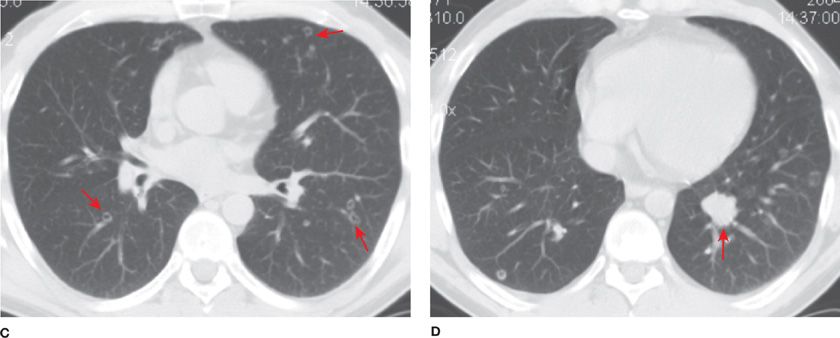

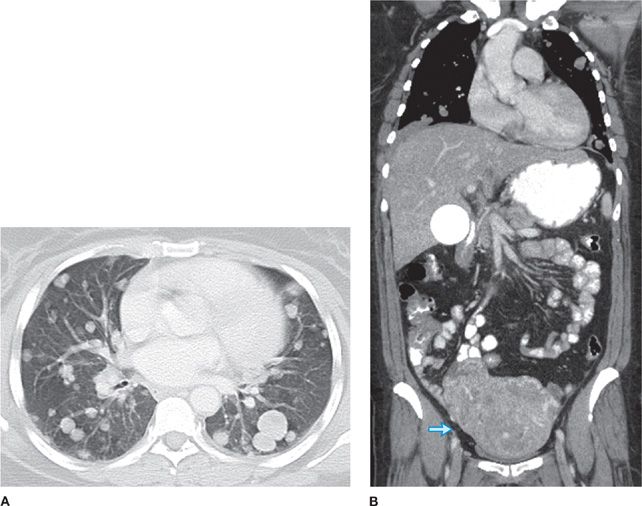

Solitary bronchial papillomas affect adults in their fifth to seventh decades. When present, obstructive bronchiectasis may necessitate resection of distally destroyed lung. Parenchymal lesions are rare and can be associated with diffuse viral contamination or dissemination of fragments related to prior tracheostomy or surgical excision.6,7 Lung involvement manifests as multiple slow-growing solid or cavitary nodules and carries a poor prognosis (Fig. 117-1).7

Figure 117-1 Axial images with lung algorithm from a noncontrast CT of the thorax of a 40-year-old man with laryngeal and tracheal papillomatosis with extension into the pulmonary parenchyma demonstrating polypoid lesions in the trachea (A) and right mainstem bronchus (B), multiple bilateral cavitary pulmonary nodules (arrows) (C), and lobulated solid nodule in the left lower lobe that was pathologically proven to be a squamous cell carcinoma arising in a papilloma (arrow) (D).

CAVERNOUS HEMANGIOMA

CAVERNOUS HEMANGIOMA

Cavernous hemangiomas of the lung are found in all age groups and may be single or multiple.8,9 They may cause symptoms of hemoptysis, respiratory distress, or congestive heart failure. Histologically, cavernous hemangioma consists of flattened endothelial cells lining dilated vascular spaces. These cells stain positive for anti-von Willebrand factor antibody and CD34, identifying them as endothelial in origin. Treatment for solitary lesions is excision.

SCLEROSING HEMANGIOMA

SCLEROSING HEMANGIOMA

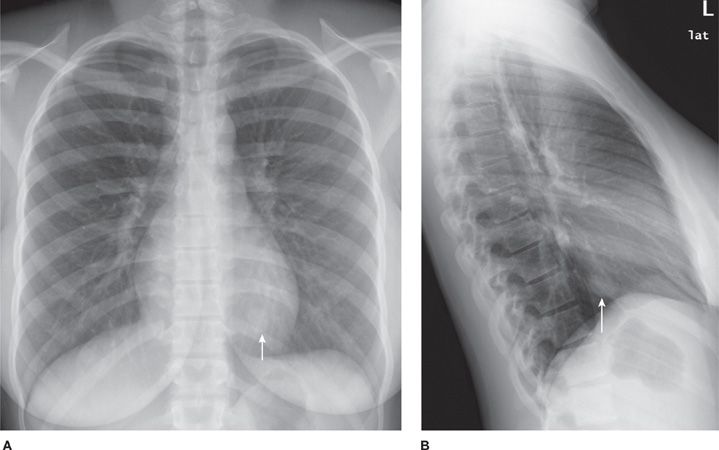

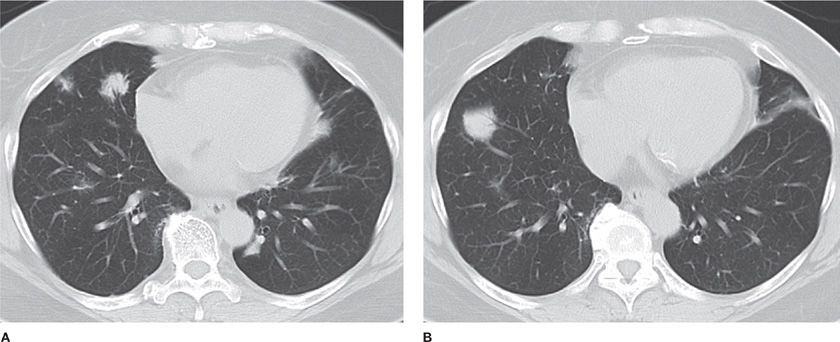

Sclerosing hemangioma (SH) is an epithelial tumor arising from respiratory epithelium. Histologically, the tumor has four components: solid, papillary, sclerotic, and hemorrhagic.10 The majority of patients are women, predominantly middle-aged.10–14 There is a higher incidence in Asia. Most patients are asymptomatic, but can present with chest pain, cough, pleurisy, and hemoptysis. SH appears as a solitary, juxta-pleural, well-defined nodule (Fig. 117-2) with smooth margins and strong enhancement. Calcifications are reported in 30% to 40%.11,12 Tumors can be multiple and bilateral. There are very rare reports of lymph node metastases. Imaging and bronchoscopy are often not sufficient to make the diagnosis and resection is indicated. PET can show false-positive results. Limited, but complete resection is usually curative.

Figure 117-2 Frontal (A) and lateral chest (B) radiographs demonstrating a well-defined nodule at the left lung base (arrows) of a 21-year-old woman with a sclerosing hemangioma.

CHONDROMA

CHONDROMA

Chondromas of the lung may be solitary or multiple, unilateral or bilateral, and are usually asymptomatic slow-growing tumors. The association of multiple peripheral pulmonary chondromas with gastric stromal sarcoma and extra-adrenal paraganglioma has been described as the “Carney triad”.15 The majority of patients with Carney triad are young women. Chondromas consist almost exclusively of cartilage that may be calcified or ossified. The presence of a fibrous pseudocapsule and the absence of fat and entrapped epithelium distinguish chondroma from pulmonary hamartoma.16 Chondromas present as calcified nodules and can sometimes be mistaken for gastric sarcoma metastases. Lung-sparing resections are curative in 44% of patients, the rest develop new chondromas. MRI-guided laser thermotherapy has been described for ablation of multiple chondromas.17

INTRAPULMONARY SOLITARY FIBROUS TUMOR

INTRAPULMONARY SOLITARY FIBROUS TUMOR

Solitary fibrous tumors (SFTs) are distinct spindle cell neoplasms that usually grow on a stalk arising from the visceral pleura18,19 and are almost always diagnosed following resection of an asymptomatic lung mass found on routine radiography. These tumors are classified as benign or malignant based on histologic findings such as mitotic activity, pleomorphism, presence of necrosis, and invasiveness.19 Tumor cells are immunoreactive for vimentin but not keratin, desmin, or actin, suggesting fibroblastic differentiation from a submesothelial origin.18 They are also positive for CD34.

SFTs that arise within the lung parenchyma without histologic continuity with the pleura are extremely rare. Intrapulmonary SFTs may contain entrapped alveolar epithelium within the spindle cell proliferation.19 Clinically, intrapulmonary SFTs are assumed to behave similarly to the pleural tumors. Radiographically, the tumor appears as an oval or round nodule or mass of variable size. Treatment is resection and prognosis is generally good. It has been reported, however, that neither the size of the tumor nor its morphology is reliable predictor of clinical behavior and biologic potential of these tumors.20 Adequate excision and follow-up are necessary.

INFLAMMATORY MYOFIBROBLASTIC TUMOR (PLASMA CELL GRANULOMA)

INFLAMMATORY MYOFIBROBLASTIC TUMOR (PLASMA CELL GRANULOMA)

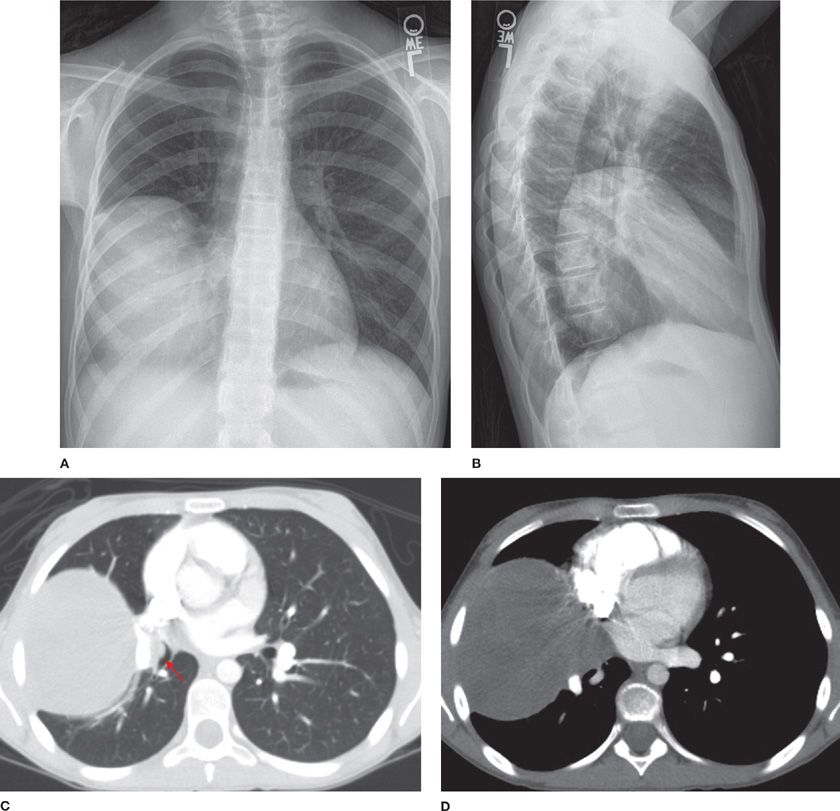

Inflammatory myofibroblastic tumor (IMT) is more commonly seen in children and adolescents, though it is also found in adults and has no gender predilection.7,21–23 Patients are usually symptomatic, presenting with cough, fatigue, or weight loss. Previously thought to be an unchecked inflammatory response to viral/foreign antigens, IMT has been confirmed to be of neoplastic origin. Rearrangement of the anaplastic lymphoma kinase gene on chromosome 2p23 results in the expression of the ALK-1 protein. IMT is locally aggressive, can be multifocal, relapse and even metastasize. Radiographically, IMT presents as a mass or nodule with lobulated or spiculated borders closely related to the airways (Fig. 117-3). Calcification and cavitation are rare.7 Histologically, plasma cells and spindle cells are seen with varying degrees of mitosis, necrosis, and vascular invasion. Tumors stain for vimentin, actin, and epithelial membrane antigen. Transbronchial/transthoracic biopsy often reveals mixed inflammatory cells with predominantly plasma cells in a background of fibroblastic proliferation, granulation tissue, and histiocytes with nuclear atypia. Thus, both fine-needle aspiration and frozen section are nonspecific and complete resection is necessary for establishing a diagnosis. Incomplete resection can result in recurrence, which can be treated with repeat resection. Symptoms, incomplete resection, as well as large size are predictors of mortality. Steroids, nonsteroidal antiinflammatory drugs, and laser therapy have been used with variable results in cases where complete resection cannot be achieved. Treatment with chemotherapy and radiation therapy remains controversial.23

Figure 117-3 Frontal (A) and lateral chest (B) radiographs demonstrating a large mass in the right hemithorax and axial images (C, D) from a contrast-enhanced CT of the thorax demonstrating a well-defined mildly heterogeneous mass with an endobronchial component (arrow) of an 11-year-old girl with an inflammatory myofibroblastic tumor.

GRANULAR CELL MYOBLASTOMA

GRANULAR CELL MYOBLASTOMA

Granular cell tumors are uncommon benign neoplasms that are thought to arise from Schwann cells.24 Usually discovered incidentally on a chest radiograph, they are endobronchial in location and multicentric. Peribronchial extension is seen in half of the tumors. However, distant metastases have not been reported. They occur equally in men and women, with a median age of 42 years. Microscopically, sheets of granular cells with abundant lysosomes, which stain positive with periodic acid–Schiff stain, are present. Tumor cells also stain positive for S-100 and myelin basic proteins. Large tumor size, necrosis, increased mitosis, and p53 as well as Ki-67 immunoreactivity are consistent with malignant change. Treatment consists of local excision, either endoscopically (laser) or by sleeve resection. Larger resections are reserved for postobstructive bronchiectasis or abscess. Up to 13% of granular cell tumors coexist with other neoplasms such as esophageal, renal, and lung carcinomas.

HAMARTOMA

HAMARTOMA

Hamartomas (mesenchymomas) are the most common benign tumors of the lung and are commonly seen in males in the sixth decade.25–28 They are slow growing and can be multiple. The majority are detected incidentally as peripheral round nodules on a chest radiograph. Only 20% are endobronchial (Fig. 117-4). The classic popcorn calcification is seen in 30% of hamartomas. Histologically, hamartomas consist of cartilage, fat, bone, connective tissue, and smooth muscle cells surrounding clefts lined with bronchial epithelium. Presence of fat and calcifications helps make the diagnosis on CT. Use of chemical shift MRI has been investigated as a tool to detect fat deposits in hamartomas with inconclusive CT findings.29 Fine-needle aspiration has a high false-positive rate and low accuracy in diagnosing hamartomas. Malignant transformation is rare. Therefore, small peripheral hamartomas may be safely observed. Excision is indicated for obstructive symptoms or if the diagnosis is in doubt. Parenchyma-sparing resection should be performed. Recurrences are rare, although hamartomas may be associated with increased risk of developing primary lung cancers.30

Figure 117-4 Radiographic appearance of a hamartoma. A. Frontal radiograph of the chest demonstrating a well-defined nodule with “popcorn” calcification in the left upper lobe. B. Axial image from a noncontrast CT demonstrating a well-defined nodule with course calcification and foci of fat.

LEIOMYOMA

LEIOMYOMA

Primary solitary leiomyoma accounts for 2% of all benign lung tumors and may present as endobronchial obstruction or as an asymptomatic peripheral radiographic nodule. Typically, primary solitary leiomyoma affects patients in their fourth decade. The tumor is slightly more common in women. Surgical resection is the treatment of choice, although laser resection of endobronchial tumors offers prolonged palliation.

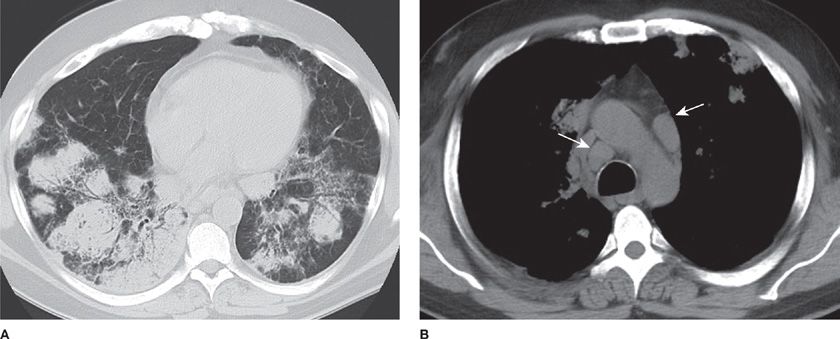

Benign metastasizing leiomyoma consists of multiple pulmonary nodules of well-differentiated smooth muscle, resulting from hematogenous spread from a benign uterine leiomyoma (Fig. 117-5).31–33 Tumors are strongly positive for Smooth Muscle Actin (SMA) and negative for CD117. Benign metastasizing leiomyoma is ER and PR positive and may respond to hormonal therapy.

Figure 117-5 Axial image (A) with lung algorithm from a contrast-enhanced CT of the thorax, abdomen, and pelvis demonstrating multiple bilateral well-defined pulmonary nodules and coronal reformatted image (B) with soft tissue window from the same study demonstrating enlarged heterogeneous uterus (arrow), consistent with multiple leiomyomas, of a 55-year-old woman with a history of uterine leiomyomas and benign metastasizing pulmonary leiomyomas.

MALIGNANT TUMORS

The diverse spectrum of malignant primary lung tumors, other than bronchogenic carcinoma, is discussed below.

PULMONARY BLASTOMA

PULMONARY BLASTOMA

Pulmonary blastomas are divided into three subgroups: biphasic pulmonary blastoma (BPB), well-differentiated fetal adenocarcinoma (WDFA), and pleuropulmonary blastoma (PPB).34–38 WDFA contains neoplastic epithelial glandular elements in an endometrioid pattern without mesenchymal malignancy. PPB is a dysontogenetic neoplasm having mesenchymal malignant elements (liposarcoma, rhabdomyosarcoma, or chondrosarcoma) without epithelial malignancy. BPB contains both epithelial and mesenchymal malignant elements, which mimic fetal lung. PPB is further subclassified as type I (purely cystic), type II (cystic and solid), and type III (purely solid). PPB occurs in infants and young children; WDFA and BPB occur in young adults, with a mean age of 35 years. Many patients with BPB and WDFA have a history of tobacco use. All three are fast-growing tumors that present in the periphery of the lung with a predilection for the lower lobes. Patients may be asymptomatic or may present with cough, hemoptysis, dyspnea, chest, or back pain. Radiographically, pulmonary blastomas appear as large solitary smooth masses. Fine-needle aspiration is usually nondiagnostic due to extensive necrosis and lack of cellular material. Neoadjuvant chemotherapy has been used to downstage the tumors before surgical resection. Adjuvant chemotherapy is combined with local radiation for control after resection. Poor prognostic factors are large tumor size, mediastinal or pleural involvement, and nodal metastasis. The central nervous system is the most common site of distant metastasis. Mutations of p53 gene are seen more frequently with BPB and PPB than with WDFA, suggesting a worse prognosis. Type II and III PPBs have an overall survival of 42% at 5 years, despite multimodality treatment.

CARCINOID

CARCINOID

Carcinoid tumors are malignant neuroendocrine tumors arising from Kulchitsky (APUD system) cells and are classified by the World Health Organization into typical carcinoid (TC) and atypical carcinoid (AC) on the basis of presence of necrosis and mitotic activity.39,40 Mean age at presentation is 55 years, but AC is seen in significantly older patients with a history of smoking. Seventy-five percent of carcinoids are central, endobronchial tumors and present commonly with postobstructive pneumonia, hemoptysis, or wheezing. Uncommonly, carcinoids may present with paraneoplastic syndromes such as Cushing syndrome due to ectopic adrenocorticotropic hormone production, or even acromegaly from ectopic growth hormone and insulin-like growth factor-1 production.

Radiologically, carcinoids present as solitary nodules (30%), infiltrates (60%), and calcified nodules (30%) (Fig. 117-6). CT scan reveals a well-defined central tumor deforming an airway with punctate calcification and homogeneous contrast enhancement with or without hilar lymphadenopathy. Carcinoids demonstrate high signal intensity on T2-weighted MRI41 and are hypometabolic on FDG-PET scans. Somatostatin receptor scintigraphy can be used in detecting occult primary tumors, staging, and localization of metastatic disease.

Figure 117-6 Atypical carcinoid in a 74-year-old woman. Axial image with lung algorithm from a noncontrast CT of the thorax demonstrating a well-defined mildly lobulated nodule in the lingula with extension into the lingular bronchus. Incidentally noted is diffuse mosaic attenuation of the pulmonary parenchyma, consistent with air trapping, a nonspecific sign of small airway disease.

Bronchoscopy frequently demonstrates a polypoid pinkish/yellow mass with intact overlying epithelium. Brushings and washings are usually nondiagnostic. Endobronchial biopsy is diagnostic in approximately 50% of patients, but rarely may precipitate a carcinoid crisis.

Carcinoids are characterized by an organoid growth pattern with uniform cells containing finely granular eosinophilic cytoplasm and nuclei with a fine chromatin pattern. Chromosome analysis shows evidence of 11q and 3p deletion in AC, with loss of 18q in metastatic carcinoid. Overexpression of p53 and loss of heterozygosity of 11q13 are seen in AC, which correlates with tumor aggressiveness. Five percent of patients with MEN I syndrome have associated sporadic carcinoids. Inactivation of the MEN I gene is seen in 67% of TC, and 25% of AC.

Treatment of choice for TC is surgical resection. Lobectomy and lymph node dissection are preferred because 20% of TC and 60% of AC are associated with nodal metastases. Bronchoplastic sleeve resection for central lesions of early-stage TC is preferable to pneumonectomy. cis-Platinum and etoposide-based chemotherapy is indicated for unresectable disease, as well as metastases. However, the response rate is only 22%, with a median survival of 20 months. Biotherapy with interferon alpha and octreotide is used for the treatment of carcinoid syndrome with symptomatic relief in 70% of patients. Liver embolization can be used to debulk liver metastases in symptomatic patients. Targeted radiotherapy with radiolabelled octreotide or metaiodobenzylguanidine remains investigational.

Recurrence-free survival is common in patients with TC. Tumor histology and nodal status are the main predictors of mortality. Completeness of resection, symptoms, and age are also significant prognostic factors. Five-year survival rates following complete resection of TC and AC are 87% to 100% and 44% to 77%, respectively. Survival decreases to 25% to 69% in the presence of nodal metastases. There is no correlation between tumor size and presence of nodal involvement. Sixty-three percent of patients with nodal mediastinal metastases develop distant metastases, most commonly in the liver. Carcinoid syndrome occurs rarely (2%) and results from release of 5-HT. Urinary 5-HIAA is used to monitor disease activity in patients with carcinoid syndrome.

CARCINOSARCOMA

CARCINOSARCOMA

Carcinosarcoma is a biphasic tumor consisting of carcinomatous and sarcomatous elements containing differentiated cartilage, bone, or skeletal muscle.42–44 This tumor is seven times more common in males than in females. The median age at presentation is 65 years. The upper lobes are affected in 60% of cases. Carcinosarcomas are divided into two groups: central endobronchial and peripheral solid parenchymal (Fig 117-4). Symptoms of airway obstruction or postobstructive pneumonia are common. However, one-third of all patients are asymptomatic. These tumors eventually invade the mediastinum and chest wall, causing pain.

Carcinosarcomas are firm, rubbery, or fleshy masses with areas of necrosis and cavitation. The carcinomatous elements are squamous cell carcinoma (46%), adenocarcinoma (31%), and adenosquamous carcinoma (19%). The sarcomatous elements are rhabdomyosarcoma (51%), chondrosarcoma, and osteosarcoma. The carcinomatous elements are often displaced to the periphery, suggesting rapid growth of the central sarcomatous elements, which form the bulk of the tumor. Immunohistochemical staining for keratin is positive for both the epithelial and mesenchymal components, suggesting that carcinosarcomas are of a monoclonal epithelial origin that has undergone sarcomatoid metaplasia. Metastases are found in lymph nodes, bone, kidney, liver, and lung and commonly contain only one of the components of the primary tumor. Complete surgical resection is usually possible and the 5-year survival rate ranges between 21% and 49%. Endobronchial location and tumor stage do not correlate with survival. However, tumor size greater than 6 cm is associated with poor survival.

EPITHELIOID HEMANGIOENDOTHELIOMA

EPITHELIOID HEMANGIOENDOTHELIOMA

Originally named intravascular bronchoalveolar tumor (IVBAT), this neoplasm has since been demonstrated to be of endothelial origin on the basis of immunohistochemical staining for factor VIII-related antigen, CD31, CD34, and/or FLI-1.45,46 Epithelioid hemangioendothelioma is best considered a low-grade sarcoma and is usually multicentric in origin. It is a disease of young women, with over 70% of cases seen in women with mean age of 40 years. Patients are usually asymptomatic, though they may present with respiratory symptoms. Multiple perivascular nodules less than 1 cm in diameter or diffuse thickening of interlobular septae are present on CT scan. Microscopically, epithelioid hemangioendothelioma consists of eosinophilic cells forming trabeculae or nests with characteristic central acellular sclerotic areas and lymphovascular and bronchiolar invasion. Pleural, intravascular, and endobronchial spread is associated with a poor prognosis, as are liver and lymph node metastases. Complete resection is the treatment for localized tumors.47 Diffuse tumors have been treated with chemotherapy, interleukin-2, and interferonalpha-2b with mixed results. Radiation is ineffective and is used only for palliation of bone pain. Partial spontaneous regression has also occasionally been reported.

LYMPHOMAS

LYMPHOMAS

Primary pulmonary lymphomas account for less than 1% of all lung cancers. Criteria used for the diagnosis of primary pulmonary lymphoma include involvement of the lung with or without mediastinal involvement and absence of extra thoracic lymphoma at the time of diagnosis or for 3 months thereafter.48

Primary pulmonary B-cell non-Hodgkin lymphoma (NHL), also known as MALT (mucosa-associated lymphoid tissue) or BALT (bronchus-associated lymphoid tissue), accounts for up to 80% of primary pulmonary lymphomas. This small low-grade B-lymphocyte lymphoma is associated with a 5-year survival greater than 80%. The tumor is thought to arise due to chronic inflammation secondary to smoking, infection, or autoimmune disease (Sjogren syndrome, rheumatoid).49 Age of onset is typically 50 to 60 years, with equal gender distribution. Respiratory symptoms include cough, dyspnea, and hemoptysis; half of the patients are asymptomatic. Extrapulmonary symptoms such as fever and weight loss occur in less than one quarter of patients. Radiographically, a localized alveolar opacity with blurred margins is seen, often associated with air bronchograms (Fig. 117-7). CT demonstrates bilateral multifocal disease in 70% of cases. CT-guided biopsy is diagnostic in 25%. Bronchoalveolar lavage is diagnostic if a lymphocytic alveolitis is present with B lymphocytes constituting greater than 10% of the total cells. Microscopically, MALT is defined as a lesion containing small lymphoid cells, lymphoepithelial lesions showing migration of lymphoid cells from the marginal zone to bronchiolar epithelium, reactive follicular hyperplasia, and rare blastic cells. Immunohistochemistry demonstrates B cell phenotype (CD19, CD20) and monoclonality. Bone marrow biopsy may show involvement in 25% of cases. Evaluation of other mucosal sites with upper endoscopy, ENT examination, and CT scan of salivary and lacrimal glands should be performed. Serum immunoelectrophoresis will reveal a monoclonal gammopathy (IgM) in 20% to 60% of patients. Elevated beta-2 microglobulin is associated with a poor prognosis. Solitary tumors should be removed. Long-term surveillance is necessary due to late local or systemic relapse after resection. Chemotherapy is recommended for residual, bilateral, progressive, or recurrent disease. Various regimens including CHOP (cyclophosphamide, doxorubicin, vincristine, and prednisone) and rituximab have been used with success.

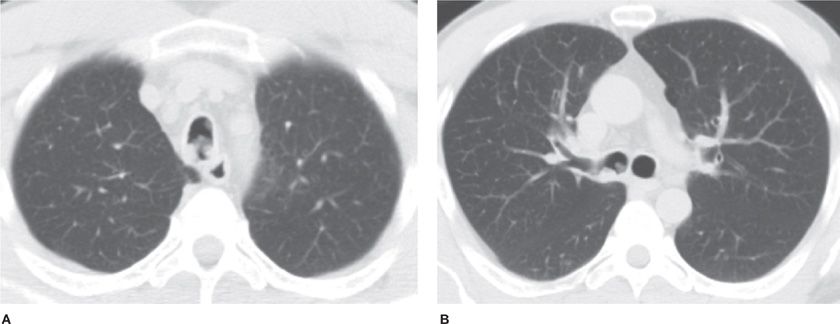

Figure 117-7 Axial images with lung algorithm from a non-contrast CT of the thorax demonstrating irregularly marginated pulmonary opacities with air bronchograms in the right middle (A) and right lower lobes (B) of a 60-year-old woman with mucosa-associated lymphoid tissue.

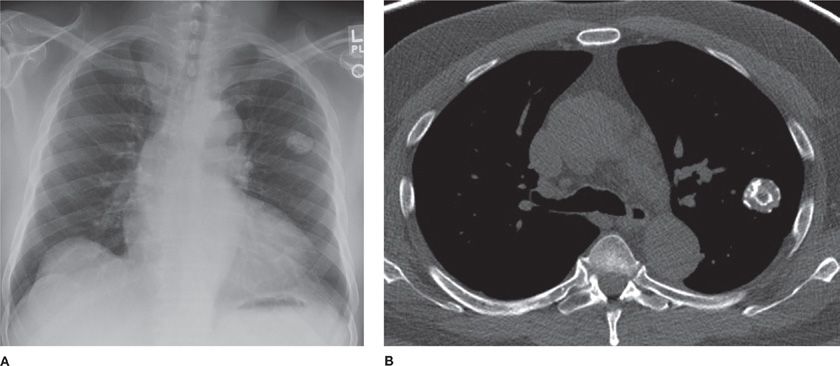

High-grade NHL-B, also known as large B-cell lymphoma, accounts for up to 15% of primary pulmonary lymphomas. Immunosuppression, HIV infection, and Sjogren syndrome are underlying disorders often associated with large B-cell lymphomas. These lymphomas are usually found in older patients and commonly present with either pulmonary or systemic symptoms. Radiologic presentation includes solitary or multiple nodules, masses, consolidations, adenopathy, pleural effusion, and, rarely, direct chest wall invasion (Fig. 117-8).50 Bronchoscopy may reveal infiltrative bronchial stenosis. Transbronchial biopsy is often diagnostic. Microscopically, large blast-like lymphoid cells with frequent mitosis, necrosis, and bronchovascular invasion are seen. Survival is poorer than in small B-cell lymphomas, especially in those patients with underlying disorders. Resection is followed by combination chemotherapy. Progression of disease and recurrence occur earlier and more commonly than in small B-cell lymphoma.

Figure 117-8 Representative axial CT images from a 49 year-old man with AIDS and diffuse large B-cell lymphoma. A. Lung window demonstrating ground glass and consolidative opacities with rounded configuration and air bronchograms in the lower lobes bilaterally. B. Soft tissue window demonstrating mediastinal lymphadenopathy (arrows).

Lymphomatoid granulomatosis (LG), also known as an angiocentric immunoproliferative lesion (AIL), presents with either pulmonary or systemic symptoms and commonly affects patients in their sixth decade. Radiographically, multiple bilateral ill-defined nodular opacities, mainly affecting the lower lobes, are seen. These opacities can cavitate and disappear secondary to infarction of the granulomatosis lesions. Extrapulmonary involvement occurs in the CNS, skin, upper respiratory tract, or renal systems. Neurologic deficits can be central or peripheral. Skin lesions include erythema or nodules, with or without ulceration. Joint, ocular, and gastrointestinal manifestations have also been reported. Microscopically, an angiocentric lymphocytic infiltrate mixed with occasional large blastic cells compressing the lumen of arterioles and eroding into bronchioles is seen. Immunohistochemistry demonstrates the B cell origin of the lymphocytes, which also express Epstein–Barr virus latent membrane protein. Initial assessment should include brain MRI, CT scan of the abdomen for renal or lymphoid involvement, and a bone marrow biopsy. Localized LG should be removed. Combination chemotherapy is reserved for diffuse disease. Radiotherapy is useful for CNS involvement. Despite aggressive therapy, median survival approximates 4 years. Poor prognostic factors include early age of onset, CNS involvement, hepatosplenomegaly, leukopenia, fever, anergy, and predominant blast cells with necrosis.

There are only 13 cases reported of NK/T cell primary pulmonary lymphoma. Patients are elderly and females are affected twice as commonly as males. Radiographically, bilateral diffuse nodularities are seen. Diagnosis requires a surgical lung biopsy and immunohistochemistry, which reveals T cell markers. Microscopically, homogeneous cells with architectural effacement and dysplasia are seen. Monoclonality of the T cells is demonstrated by TCR gene rearrangement. Prognosis is very poor despite surgical resection and CHOP-based chemotherapy.

Primary pulmonary Hodgkin lymphoma peaks in the third and sixth decades. Most patients are females. Symptoms may be respiratory or systemic. Radiographically, multinodular and massive parenchymal involvement is seen with occasional cavitation. Bronchoscopy and Broncho-alveolar Lavage (BAL) are inconclusive and surgical lung biopsy is required to confirm the diagnosis. The most frequent histologic subtype is the nodular sclerosing variety. Combination chemotherapy, radiation, and surgery are the common modalities of treatment. Multilobar or bilateral disease is associated with a poor prognosis.

PLASMACYTOMA

PLASMACYTOMA

Plasmacytomas arise from monoclonal plasma cells. The diagnostic criteria for extramedullary plasmacytoma are a biopsy-proven plasma cell proliferation and the absence of bone marrow infiltration, osteolytic lesions, renal failure, and hypercalcemia.51–53 The average age at presentation is 54 years with equal distribution between males and females. Plasmacytomas commonly present as a hilar mass, but lobar consolidation or bilateral diffuse infiltrates with air bronchograms may also be seen. Serum electrophoresis reveals an M-protein spike, which usually consists of IgG kappa chains, and correlates with the tumor burden. Treatment is surgical resection, but chemotherapy with melphalan and prednisolone has been used with good results. The 5-year survival rate is 40%. These tumors need to be distinguished from marginal zone B-cell lymphomas of MALT origin. Forty percent of patients develop multiple myeloma and so surveillance with serum and urine electrophoresis, bone marrow biopsy, skeletal bone survey, and clinical monitoring is necessary.

MELANOMA

MELANOMA

Primary pulmonary melanoma is an extremely rare lung tumor for which several theories have been suggested: aberrant migration of melanocytes from the primitive foregut, melanogenic metaplasia of bronchial epithelium, or melanocytic differentiation of neuroendocrine precursor Kulchitsky cells.54–58 Jensen and Egedorf first suggested the clinical criteria for the diagnosis of primary pulmonary melanoma: (1) no previously removed skin or ocular melanomas, (2) solitary tumor, (3) morphology compatible with a primary tumor, (4) no melanoma in other organs at surgery, and (5) no evidence of primary elsewhere on autopsy.54 Histopathologic criteria include junctional change with nesting of malignant cells beneath bronchial epithelium, and invasion of bronchial epithelium in an area without ulceration. Aggressive resection is the treatment of choice and offers the best chance for cure. Chemotherapy and immunotherapy are used for widespread disease.

MALIGNANT GERM CELL TUMORS

MALIGNANT GERM CELL TUMORS

Malignant teratoma and choriocarcinoma are the two malignant germ cell tumors that arise in the lung.59 Teratomas show elements from all three germ layers. Half of the primary pulmonary teratomas are malignant. Patients present with cough, hemoptysis, or chest pain. The most specific symptom—trichoptysis—is rarely present. Radiographically, the mass may show calcification with peripheral radiolucency. Resection is the treatment of choice. Adjuvant chemotherapy is usually a combination of cis-platinum, bleomycin, and etoposide.

Choriocarcinomas are usually seen in women or elderly men who present with symptoms of feminization. The most common symptom is hemoptysis. Various theories have been postulated to explain the origin of pulmonary choriocarcinomas: neoplastic transformation of misplaced primordial germ cells, spontaneous regression of an occult genital primary leaving behind pulmonary metastatic lesions, neoplastic transformation of placental emboli at the time of delivery or abortion, and neoplastic transformation of somatic neoplastic cells. The choriocarcinoma syndrome consists of bleeding from the primary lung lesion and elevation of beta-human chorionic gonadotropin (β-HCG). Choriocarcinoma can be distinguished from a large cell carcinoma producing ectopic β-HCG by immunohistochemistry, which will stain for thyroid transcription factor-1 (a marker of pulmonary origin) and not for β-HCG. Histologically, cytotrophoblastic cell nests are seen covered by syncytiotrophoblasts, with evidence of widespread necrosis and hemorrhage, as well as a lack of fibrovascular stroma. Surgical resection followed by adjuvant chemotherapy is recommended. Unlike their gestational counterparts, pulmonary choriocarcinomas are unresponsive to radiotherapy. Distant metastases can occur in the brain, kidneys, and contralateral lung.

SALIVARY GLAND-TYPE TUMORS

SALIVARY GLAND-TYPE TUMORS

Adenoid cystic carcinoma (ACC) is the most common salivary-gland tumor found in the lung60 and is thought to arise from ductal/myoepithelial cells of bronchial submucosal glands. Centrally located ACC arises in the trachea or mainstem bronchi and presents as an exophytic endobronchial mass causing obstructive symptoms. Overlying mucosa is often grossly normal. Peripheral ACC is uncommon. Males and females are equally affected. Histologically, there are three subtypes: cribriform, tubular, and solid. ACCs are slow-growing neoplasms that exhibit centripetal spread in the airways as well as perineural growth. Therefore, extensive resections are required. These tumors are extremely radiosensitive and local recurrences or residual disease may be treated with radiation. Following complete resection, 5- and 10-year survival of 91% and 76%, respectively, have been reported.

Mucoepidermoid carcinomas usually arise in mainstem bronchi or the proximal lobar bronchi. The right bronchial tree is more commonly affected in children. Patients present with symptoms of obstruction due to a polypoid endobronchial mass. Bronchoscopic biopsy is diagnostic. Three histologic grades have been defined (low, intermediate, and high) based upon the presence of cystic spaces, cell type (mucus cells, intermediate cells, and epidermoid cells), cellular pleomorphism, and mitosis. Complete resection with mediastinal lymph node dissection is the treatment of choice. High-grade tumors are more common in adults and may invade adjacent structures, lymph nodes, vascular, and perineural spaces. Incomplete resection is more likely in high-grade tumors and postoperative chemoradiation may be necessary. High-grade tumors are uniformly fatal in 11 to 28 months.

Acinic cell tumors (Fechner tumors) are usually found in the salivary glands and hence a diligent search for an extrathoracic primary is essential. Symptoms vary and are determined by whether the tumor is centrally located in the airway or peripheral in location. Histologically, these tumors demonstrate a pattern resembling a neuroendocrine tumor and may need to be differentiated from the more common carcinoid tumor. Acinic cell tumors are slow-growing and recurrence or metastases after complete excision has not been reported.

SARCOMAS

SARCOMAS

Primary pulmonary sarcomas account for less than 0.5% of all lung tumors.61 Mean age at presentation is 53 years with a slight predominance in males. A history of smoking or previous radiation exposure may be present. Usual symptoms are chest pain and cough. Sarcomas appear as large (mean diameter 5 cm), solitary peripheral, or hilar nodular opacities usually located in the upper lobes. Bronchoscopy may show either extrinsic compression or a polypoid endobronchial mass. The variety of soft tissue pulmonary sarcomas reflects the range of mesenchymal tissue found in the lung (Table 117-3). The most common primary pulmonary sarcoma is leiomyosarcoma (30%), followed by malignant fibrous histiocytoma and synovial sarcoma. Histologic subtypes can be differentiated on the basis of immunohistochemical markers such as vimentin, desmin, actin, and epithelial membrane antigen. Treatment is wide resection with mediastinal lymph node dissection. Residual disease is treated with radiotherapy or re-resection. Recurrences can be resected with good results. Ifosfamide-based chemotherapy has also been used in the neoadjuvant and adjuvant setting for positive margins or positive lymph nodes. Median survival is 48 months and 5-year survival is 38% to 69%. Size and grade do not correlate with increased mortality. Incomplete resection is associated with poor survival.