CHAPTER 3 Preoperative Evaluation of Patients Undergoing Thoracic Surgery

PHYSIOLOGIC EFFECTS OF THORACIC SURGERY

Surgical procedures and the anesthesia administered to allow such procedures have significant impact on respiratory physiology that contributes to the development of postoperative pulmonary complications. Given that the incidence of pulmonary complications is directly related to the proximity of the planned procedure to the diaphragms, patients undergoing pulmonary, esophageal, or other thoracic surgical procedures fall into the category of patients at high risk for postoperative respiratory complication.1

In the postoperative period, a variety of factors contribute to the development of complications. These include an alteration in breathing pattern to one of rapid shallow breaths with the absence of periodic deep breaths (sighs) and abnormal diaphragmatic function. These result both from pain and from diaphragmatic dysfunction resulting from splanchnic efferent neural impulses arising from the manipulation of abdominal contents. This has the effect of reducing the functional residual capacity (FRC), the resting volume of the respiratory system. The FRC declines by an average of 35% after thoracotomy and lung resection and by about 30% after upper abdominal operations.2–4 If the FRC declines sufficiently to approach closing volume, the volume at which small airway closure begins to occur, patients develop atelectasis and are predisposed to infectious complications. Closing volume is elevated in patients with underlying lung disease.

PATIENT POPULATION UNDERGOING THORACIC SURGERY

Many patients undergoing a noncardiac thoracic surgical procedure do so because of known or suspected lung or esophageal cancer. These diseases share the common risk factor of a significant and prolonged exposure to cigarette smoking. The combination of age and prolonged cigarette smoking results in a patient population with a significant incidence of comorbid factors in addition to the primary diagnosis. Several reports use the Charlson Comorbidity Index as an indicator of comorbid conditions and predictor of postoperative complications. This index generates a score based on the presence of comorbid conditions and has been demonstrated to stratify risk of postoperative complications in thoracic surgery patients.5,6

In one study, the mean age of patients undergoing esophagectomy was 58.1 years; 45% of patients were older than 60 years.7 In another Japanese study, the median age was 62.3 years; 88% were male.8 In a study comparing transhiatal esophagectomy with transthoracic esophagectomy, the mean ages of the patients were 69 years and 64 years, with patients up to the age of 79 years included in the study.9 In a review, 28% to 32% of patients undergoing esophagectomy in the United States were older than 75 years, and 40% had a Charlson score above 3.10

Similarly, patients with lung cancer tend to be older and have comorbid conditions. In a series of 344 patients, 36% were older than 70 years and 95% had a significant smoking history.11 A review of Medicare patients undergoing thoracic surgery in the United States showed that of patients undergoing lobectomy, 32% to 35% were older than 75 years (44% women), and 32% had a Charlson score above 3.10 In the same series, 21% to 26% of patients undergoing pneumonectomy were older than 75 years (28% women), and 56% had a Charlson score above 3.

Thus, the patient population presenting for major thoracic surgical procedures tends to be older, has a high incidence of comorbid conditions, and contains a disproportionate number of patients with obstructive lung disease. The combination of these factors, plus the magnitude of the surgical procedures, presents a challenge to the clinicians evaluating such patients. The potential for perioperative morbidity and mortality is substantial, but at the same time, the lack of effective alternative therapy for the patient’s malignant disease means that the consequence of not being a surgical candidate is almost certain mortality. This quandary has led Gass and Olsen12 to ask, What is an acceptable surgical mortality in a disease with 100% mortality?

MOST COMMON COMPLICATIONS AFTER THORACIC SURGERY

These are discussed in more detail elsewhere in this book (see Chapter 4). In general, the most frequent complications after major thoracic procedures fall into the categories of respiratory and cardiovascular. Although the exact frequency varies from series to series, pneumonia, atelectasis, arrhythmias (particularly atrial fibrillation), and congestive heart failure are the most common. Myocardial infarction, prolonged air leak, empyema, and bronchopleural fistula also occur at a significant frequency.11,13,14 It follows, therefore, that particular attention to pulmonary and cardiac reserve and risk factors should be a major component of the preoperative evaluation.

HISTORY AND PHYSICAL EXAMINATION

History

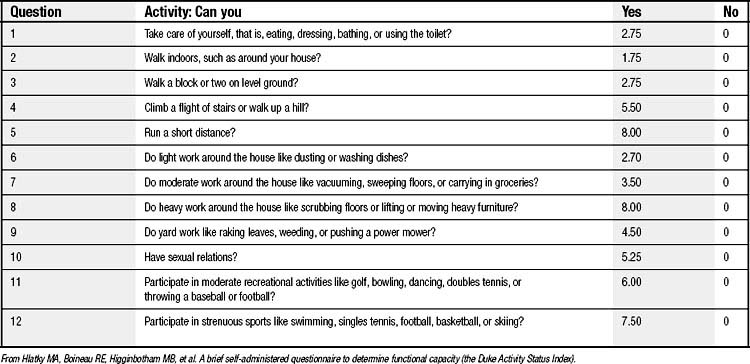

Table 3-1 highlights the important components of the patient’s history. Whereas many of the elements of the history are self-explanatory, several require some further exposition. A critical component of the preoperative evaluation is the assessment of a patient’s functional status. Functional status is an important component of the decision algorithm for both the pulmonary and cardiac elements of the preoperative evaluation. A variety of approaches have been taken to determine functional capacity. These include questionnaires; tests of locomotion, such as the 6-minute walk or stair climbing; and cardiopulmonary exercise testing (discussed later). One convenient approach to use is the Duke Activity Status Index (DASI) (Table 3-2), a questionnaire that can be administered during an interview or can be self-administered.15

Table 3–1 Important Components of History in Preoperative Evaluation

| Presenting symptoms and circumstances of diagnosis |

| Prior diagnosis of pulmonary or cardiac disease |

| Comorbid conditions: diabetes mellitus, liver disease, renal disease |

| Prior experiences with general anesthesia and surgery |

| Cigarette smoking: never, current, ex-smoker (if ex-smoker, when did patient stop?) |

| Inventory of functional capacity of patient (e.g., Duke Activity Status Index) |

| Medications and allergies |

| Alcohol use, including prior history of withdrawal syndromes |

< div class='tao-gold-member'>