Postsurgical Empyema

Joseph I. Miller Jr.

Following pulmonary infection, the second most frequent cause of empyema is the development of infection in the pleural space after surgery of the esophagus, lungs, or mediastinum (Table 62-1). Postsurgical empyema accounts for 20% of all cases of empyema. It most frequently follows pneumonectomy, occurring in 2% to 12% of patients. It may occur in 1% to 3% of patients after lobectomy. LeRoux and associates7 report that in 8% to 11% of patients, the preceding lesion causing an empyema thoracis is an unrecognized subphrenic abscess in those who have undergone an abdominal, urologic, or pelvic operation. Empyema may occur secondary to a spontaneous pneumothorax with a persistent bronchopleural fistula (BPF), it may occur after parasitic infection or secondary to retained foreign bodies in the bronchial tree, or it may have a number of miscellaneous causes. The etiology of empyema in 215 patients is given in Table 62-2. Factors that may promote the development of a postsurgical empyema are listed in Table 62-3.

Nonresectional Postsurgical Empyema

The development of nonresectional thoracic surgical empyema is related to the predisposing cause. It may follow esophageal surgery with resultant leak into the pleural space; it may develop after subdiaphragmatic surgery on the stomach, pancreas, or spleen with the accumulation of fluid in the subdiaphragmatic space. It may occur after rupture of an infected pleural bleb or secondary to lung abscess.

Infection in the pleural space unrelated to a pulmonary resection generally can be treated in the same manner as a nonsurgical empyema, with correction of the underlying cause, appropriate antibiotics, and drainage with closed chest tube thoracostomy.

Empyema After Resection

Empyema that complicates pulmonary resection must be considered separately from empyema that occurs spontaneously or after trauma. When empyema complicates a pulmonary resection that is less than a pneumonectomy, the ability of the remaining lung to fill the pleural space after management of the empyema by drainage or decortication, and thereby to obliterate the pleural space, depends on the state of the remaining lung and its location, apical or basal. Empyema after upper lobectomy nearly always requires more than simple drainage, which nearly always suffices after lower lobectomy. After pneumonectomy, the empyema space is inevitably large and nearly always permanent. In these circumstances, alternative methods of treatment include sterilization, permanent drainage, thoracoplasty, and obliteration of the space by muscle flap transposi- tion.

The incidence of empyema after pulmonary resection varies with the indications for the resection (inflammatory or neoplastic disease), with or without preoperative radiation. With resection for pulmonary tuberculosis, sputum conversion having been achieved, the incidence of BPF with empyema in the series Lynn8 reported was 6.7% after lobectomy. When sputum results were still positive for acid-fast organisms, Teixera13 reported that it was 10%.

With pneumonectomy as opposed to lesser resections, LeRoux and associates7 reported that the incidence of empyema varies from 2% to 13%. When pneumonectomy is completed through an empyema, the incidence of continued pleural infection is 45%.

Although empyema may occur at any time postoperatively, even years later, most empyemas develop in the early postoperative period. The pleural space may be contaminated at the time of pulmonary resection with the development of a bronchopleural or esophagopleural fistula or from blood-borne sources. After pulmonary resection that is less than a pneumonectomy, empyema occurs more often when the pleural space is incompletely filled by expansion of the remaining lung, mediastinal shift, and elevation of the diaphragm. Symptoms and signs vary, and if resection was performed for neoplastic disease, they may be difficult to distinguish from those caused by dissemination of tumor. The possibility of empyema must be considered in any patient with clinical features of infection after pulmonary resection. Expectoration of serosanguineous liquid and purulent discharge from the wound or the drain sites is almost always diagnostic. On radiography of the chest, usually a pleural opacity is seen, with or without a fluid level, when resection has been less than a pneumonectomy.

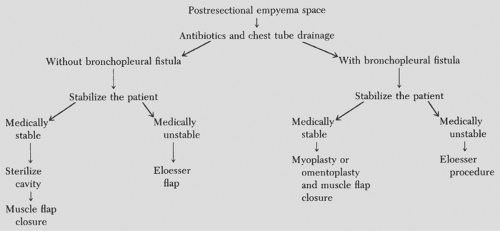

After pneumonectomy, a decrease in the fluid level early postoperatively, or the appearance of a new fluid level when the pneumonectomy site was uniformly opaque, strongly suggests an infected pleural space with BPF. The timing of surgical intervention and the type of operative procedure undertaken are tailored to the individual patient. An algorithm for the management of postresectional empyema is given in Figure 62-1.

Table 62-1 Etiology of Postsurgical Empyema | |

|---|---|

|

Table 62-2 Etiology of Empyema in 215 Patients | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Table 62-3 Factors That Promote Development of Postsurgical Empyema | |

|---|---|

|

General Principles of Treatment

When the diagnosis of postresectional empyema with or without a BPF is made, surgical drainage by closed chest tube thoracostomy and institution of appropriate antibiotic therapy are crucial. Once adequate drainage has been established and the patient is stabilized, usually in 10 to 14 days, the course of management can be determined. When recognized in the first 48 to 72 hours, reoperative intervention should be considered. After 14 days, the patient should be treated conservatively, as detailed below. If a BPF is present, the fistula should be closed by a myoplasty or omentoplasty followed by single-stage muscle flap closure of the remaining space. If the patient is medically unstable, the closed chest tube thoracostomy can be converted to open drainage by Eloesser’s procedure.

If the patient has only an empyema space without a BPF, the cavity is sterilized by irrigation with the appropriate antibiotic solution, as determined by the antibiotic sensitivities of the chest tube drainage, and a single-stage muscle flap closure of the remaining cavity is performed. A complete discussion of muscle flap closure is given later in this chapter. If the patient is medically unstable, closed chest tube thoracostomy can be converted to an open Eloesser’s flap.

Postpneumonectomy Empyema

Postpneumonectomy empyema remains a problem. It is associated with a BPF in approximately 40% of patients, and in only 20% of patients, does the BPF close spontaneously (Table 62-4).

Significant factors contributing to the development of a BPF after pneumonectomy are induction chemo/radiotherapy, a

right pneumonectomy, heavily calcified bronchial stump, and the need for postoperative mechanical ventilation.3

right pneumonectomy, heavily calcified bronchial stump, and the need for postoperative mechanical ventilation.3

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree