CHAPTER 92 Postinfarction Ventricular Septal Defect

Disruption of the ventricular septum after myocardial infarction is an infrequent event after a full-thickness myocardial infarction. The resulting clinical syndrome can range from an asymptomatic murmur to an extensive left-to-right intracardiac shunt with resulting heart failure and shock. The first approaches to surgical management emphasized delayed repair, which allowed time for fibrosis to occur so that tissue quality at the defect margins was more substantial.1,2 Modern approaches recognize that potentially salvageable patients deteriorate during this period of delay. Thus, early surgical intervention is now the accepted treatment.3

Historical Perspective

Postinfarction ventricular septal defect (VSD) was first recognized by Latham at autopsy in 1845.4 The first antemortem diagnosis was made in 1923.5 In 1956, Cooley accomplished the first successful surgical repair in a patient who had survived several weeks after septal perforation.6 Most patients in the early era were brought to operation a month or longer after surviving acute infarction in the belief that organization of the tissues surrounding the defect allowed a more secure closure.1,2 Subsequently, improvements in myocardial protection, the design and refinement of surgical techniques, improved prosthetic materials, and the widespread use of cardiac ultrasound to permit the earlier diagnosis of VSD have all contributed to making earlier successful repair of this entity a possibility.7

Incidence and Demographics

Postinfarction VSD complicates 1% to 2% of myocardial infarctions, but it accounts for 5% of deaths after myocardial infarction.8,9 The incidence appears to be declining because of aggressive pharmacologic and interventional management of acute myocardial infarction and better treatment of postinfarction hypertension.10 Postinfarction VSDs occur more frequently in males (male-to-female ratio, 3:2), reflecting the higher incidence of coronary artery disease in men. The average age is 62 years (range, 44 to 81 years). Septal rupture occurs most often after the first acute myocardial infarction.11

Etiology and Pathogenesis

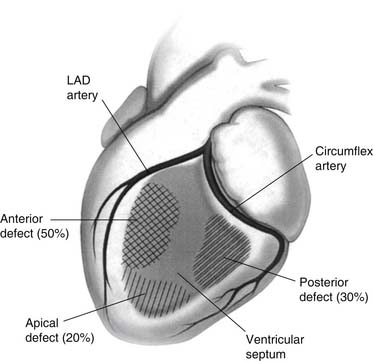

Angiographic evaluation of patients with postinfarction VSD most often reveals a completely occluded culprit coronary artery.6 Nearly two thirds of patients have single-vessel disease.12 There is usually somewhat less extensive disease in other vessels, and less collateralization.13 Postinfarction VSDs are located most commonly (i.e., in about 60% of cases) in the anteroapical septum as a result of full-thickness anterior infarction secondary to occlusion of the left anterior descending artery. Twenty percent to 40% of patients with postinfarction VSD have rupture of the posterior septum because of inferoseptal infarction secondary to occlusion of a dominant right or a dominant circumflex coronary artery (Fig. 92-1).14 Simple rupture, consisting of a direct through-and-through defect, tends to be more common and is usually located anteriorly. Complex rupture with a more serpiginous tract is less common and is usually located inferiorly. Although most patients develop a single VSD, 5% to 11% of patients may have multiple septal defects.

Figure 92–1 Distribution of postinfarction ventricular septal defects. LAD, left anterior descending.

The myocardial infarction that sets the backdrop for a postinfarction VSD tends to be extensive and has been reported to involve 26% of the free wall on average, compared with only 15% in noncomplicated acute myocardial infarctions.8 Postinfarction VSD usually develops 2 to 4 days after acute myocardial infarction, but it has been reported as early as a few hours after acute myocardial infarction and up to 2 weeks later.8,15,16 This time course correlates with histologic findings that show extensive distribution of necrotic myocardium at this time, with relatively sparse vasculogenesis, angiogenesis, or formation of fibrous connective tissue.17,18 It has been hypothesized that “slippage” of myocytes during infarct expansion may allow blood to dissect through the necrotic myocardium,whence it can enter the right ventricle (or the pericardial space in the setting of rupture of the free wall).19,20 Similarly, autodigestion of necrotic myocardium may allow fissures to form, through which blood can subsequently dissect.21

Pathophysiology

The primary determinant of outcome after postinfarction rupture of the ventricular septum is the development of heart failure (left, right, or biventricular), which is a function of both the size of the defect and the magnitude of the myocardial infarction. Left-sided heart failure tends to predominate in anterior VSDs, and right-sided failure predominates in posterior VSDs.22–24 The extent of heart failure often cannot be explained solely by postinfarction failure of the ventricle.25 With the opening of a defect in the ventricular septum, a proportion of each left ventricular ejection is diverted from the systemic circulation across the septum into the right ventricle, thereby both compromising forward systemic cardiac output and overloading the pulmonary circulation. The resulting cardiogenic shock can lead to end-organ malperfusion and organ failure, which may be irreversible and fatal. In addition, the normally compliant right ventricle may demonstrate severe diastolic failure after a prolonged left-to-right shunt. The resulting escalation in right ventricular diastolic pressures can ultimately result in flow reversal across the septum when right ventricular end-diastolic pressures exceed left ventricular end-diastolic pressures26 and compound the situation further with systemic hypoxia.

Natural History

Without surgical intervention, a quarter of patients with postinfarction VSD die within 24 hours. Half succumb to their illness within the first week, nearly two thirds die within 2 weeks, three quarters die within a month, and only 7% survive longer than 1 year.11,27,28 These data have been confirmed in the recent SHOCK (SHould we emergently revascularize Occluded Coronaries in cardiogenic shocK) multicenter trial in which subgroup analysis of patients suffering postinfarction VSD was performed. A total of 55 patients with postinfarction VSD were enrolled in the study a median of 16 hours after infarction and went into shock 7.3 hours thereafter. Of the 24 patients managed medically, only one survived (survival rate, 4%). Of the 31 patients who underwent operation to repair the VSD, 21 underwent concomitant coronary artery bypass grafting. Of these, only six survived (survival rate, 19%). The difference between the groups was statistically significant.29

The historical practice of waiting weeks after postinfarction rupture of the ventricular septum selected out patients with lesser pathology and a relatively mild hemodynamic insult.23,30,31 It is clear that attempting to defer early operation in the hopes of maintaining hemodynamic stability deprives many patients of a chance for a successful outcome before irreversible end-organ damage supervenes.32,33

CLINICAL PRESENTATION, PREOPERATIVE MANAGEMENT, RISK STRATIFICATION

Presentation

Typically, patients with postinfarction VSD present several days after a myocardial infarction with a harsh new holosystolic murmur that may radiate to the axilla.16 In more than half of patients, this is associated with recurrent chest pain.8 Clinical signs are generally those of right-sided heart failure, and pulmonary edema is rare. The electrocardiographic findings in these patients are the changes seen in antecedent anterior, septal, inferior, or posterior infarction. Up to a third of patients may develop transient atrioventricular conduction block that precedes rupture. Chest roentgenogram is generally nonspecific. Unfortunately, there is no reliable predictor of impending rupture.

Diagnosis

The classic technique for distinguishing between acute papillary muscle rupture and postinfarction VSD has been right heart catheterization, during which a greater than 9% step-up in the oxygen saturation between the right atrium and the pulmonary artery is diagnostic of VSD in the appropriate clinical setting.23 Additional findings, such as an elevated pulmonary-to-systemic flow ratiowhich can range from 1.4:1 to 8:1, also verify the presence of the VSD and roughly correlate with size.34 Neither of these techniques accurately localizes the defect. Color flow Doppler echocardiography can show the size and location of the defect, determine ventricular function, assess pulmonary artery and right ventricular pressures, and exclude concomitant mitral valve disease with sensitivity and specificity approaching 100%.35–38

Indications for Operation and Preoperative Management

As the natural history of untreated postinfarction VSD is dismal, the diagnosis of this entity suffices as an indication for operation.33 Patients in cardiogenic shock represent a surgical emergency. Occasionally, patients are encountered who are already in established multisystem organ failure. These patients are unlikely to survive emergent repair and may benefit from a mechanical bridge (e.g., intra-aortic balloon counterpulsation or ventricular assist device) for salvage before corrective operation. Patients who are in an intermediate status between shock and stable condition need to be operated on within 12 to 24 hours after appropriate preoperative evaluations are completed. A small percentage of patients (<5%) who are completely stable with no clinical compromise can undergo repair on a semi-elective basis.

Preoperative management is directed toward maintaining hemodynamic stability and preventing end-organ damage. Specifically, therapy should be targeted toward reducing systemic vascular resistance (thereby reducing left-to-right shunting), maintaining cardiac output and peripheral perfusion, and maintaining or improving coronary blood flow. All three of these objectives can be accomplished by intra-aortic balloon counterpulsation39–41 or with directed pharmacologic therapy.

Predictors of Risk

Patients with postinfarction VSD are a heterogeneous group in which both extremes of risk (that is, very low risk as well as very high risk) are possible. For the nonemergent, stable patients, excellent results can be achieved, probability of survival to discharge from the hospital is high, and long-term survival is comparable to that in common cardiac operations. On the other hand, patients in extremis tend to have dismal outcomes (Table 92-1).

Table 92–1 Preoperative Predictors of Death after Surgical Repair of Postinfarction Ventricular Septal Defect (VSD)

| Variable | Predictor of Early Death | Predictor of LateDeath |

|---|---|---|

| Need for preoperative catecholamines | P = .001 | P = NS |

| Emergent operation | P < .0001 | P = NS |

| Anterior VSD | P = .04 | P = NS |

| Age > 65 years | P = .009 | P = NS |

| Right-side-of-the-heart failure | P = .01 | P = .005 |

| Elevation in blood urea nitrogen | P = .02 | P = NS |

| Elevation of serum creatinine | P = NS | P < .05 |

| Previous myocardial infarction | P = NS | P < .05 |

| Presence of left main coronary disease | P = NS | P < .05 |

NS, not significant.

In various studies, clinical variables have been used to identify the high-risk patient. In several studies, the use of an intra-aortic balloon pump was correlated with increased early mortality42; presumably its use was seen as a marker for disease severity. Other groups have demonstrated that posterior location of the septal rupture is associated with an increased operative mortality,23,26,43,44 which may be because the repair is more technically difficult, because the risk of mitral regurgitation is increased, or because right ventricular (RV) failure is associated with an RV infarction. Proximal VSDs (closer to the atrioventricular groove) have also been shown to strongly predict early mortality, presumably because they are associated with the largest infarctions.45

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree