Posterior Knee Dislocation

ANDREW G. GEORGIADIS and ALEXANDER D. SHEPARD

Presentation

A 37-year-old morbidly obese female (BMI 46) is brought to the emergency department after slipping on a carpet at home and presenting with left knee pain. She is triaged to a low-acuity bed. She has swelling and pain in her left lower extremity but no discernible deformity or open wounds. After examination, this is determined to be an isolated injury. At the time of orthopedic and vascular surgical consultation, dorsalis pedis and posterior tibial pulses are absent in the injured left lower extremity but are present in the uninjured right. Femoral pulses are palpable bilaterally. Sensation is grossly intact but altered on the dorsal and plantar left foot. The patient cannot tolerate any passive motion of her left knee.

Differential Diagnosis

Based on the physical exam, there is an arterial occlusion in the left lower extremity below the level of the femoral artery. Despite the lack of physical deformity in the injured extremity, the main differential diagnosis is a periarticular fracture or knee dislocation. The popliteal artery is relatively fixed proximally and distally at the adductor hiatus and fascial arch of the soleus and is therefore susceptible to injury with any traumatic knee deformity. Injury to the popliteal artery results from direct avulsion, transection, or most commonly a stretch injury leading to intimal disruption and thrombosis.

In the setting of dislocation, closed reduction must be performed immediately under appropriate pharmacologic muscle relaxation, usually administered by the emergency department physician. Reassessment of distal pulses is made thereafter.

Case Continued

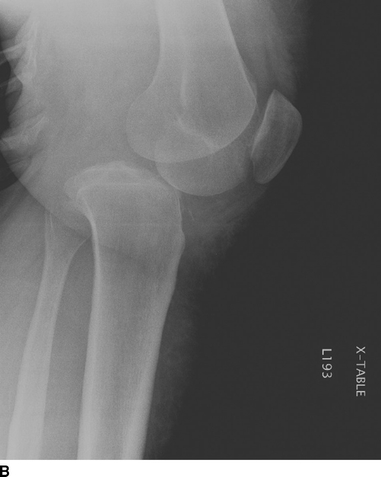

Radiographs reveal a knee dislocation with the patient’s tibia posterior to her femur (Fig. 1). Closed reduction was unsuccessfully attempted in the emergency department. Warm ischemia time at the time of attempted reduction was 4 hours. The patient was immediately taken to the operating room for closed reduction of the knee under general anesthesia with intraoperative arteriography.

FIGURE 1 Anteroposterior (A) and lateral (B) knee radiographs of a left knee posterior dislocation.

Workup

A focused history and physical are essential in determining the mechanism and chronicity of extremity ischemia. Radiographs of the knee should be obtained immediately in any patient with knee pain and an asymmetric pulse exam (Fig. 1). Hard signs of vascular injury include active hemorrhage, expanding hematoma, distal ischemia, or bruit at the injury site. Asymmetric pulses or return of a palpable pulse after reduction mandates further evaluation with Doppler-derived ankle-brachial indices (ABIs). An ABI less than 0.9 constitutes an indication for arterial imaging. Palpable pulses do not exclude vascular injury as pulse waves can propagate through developing thrombus and an undetected intimal injury can lead to later thrombotic complications. An ABI greater than 0.9 reliably excludes a significant arterial injury.

Angiography remains the gold standard for extremity arterial imaging but is increasingly being supplanted by computed tomographic angiography (CTA) particularly for injuries at or above the level of the knee. In the setting of potential knee dislocation, CTA can also provide information about the vein as well as fractures that could change management. Duplex scanning is another imaging modality that is particularly useful when trying to rule out an intimal injury in a patient with palpable pulses and reduced ABIs. In the absence of palpable pulses following reduction, further evaluation should be undertaken in the operating room.

Case Continued

After closed reduction in the operating room, the patient’s knee was grossly unstable and recurrent posterior dislocation occurred with any manipulation of the extremity. Postreduction pulses and signals were absent. Warm ischemia time at this juncture was 5 hours.

Diagnosis and Treatment

Radiographic evaluation confirms the direction of dislocation and any associated fractures. The direction of a dislocation is termed by the distal portion of the articulation, here the tibia, and anterior dislocations are more common. Early studies suggested that the popliteal artery failed by intimal tearing, stretch, and thrombosis in anterior dislocation versus frank transection in posterior dislocation. It is now known that any direction of dislocation can result in any morphology of vessel compromise. Ultimately, the direction of dislocation is irrelevant for the purposes of acute treatment. Emergent closed reduction should be performed followed by immediate reassessment of distal pulses and ABIs. In the setting of acute ischemia, patients should be immediately heparinized. If distal pulses are restored, ABIs should be performed. If the ABI is greater than 0.9, the patient can be safely observed with serial exams. If the ABI is less than 0.9, further arterial imaging is required as outlined above. Institutions with protocols for ABI-based selective arterial imaging have reported very low false-negative rates. For nonobese patients with minor changes in their ABI, we prefer duplex scanning of the popliteal artery/vein and distal vasculature. For more profound ABI changes (less than 0.8), we prefer catheter angiography or CTA. Most detected popliteal artery injuries should be repaired unless minor in nature. Intimal injuries involving less than 30% of the vessel circumference can be safely observed with serial duplex ultrasounds and ABIs. We usually treat these patients with a short course of anticoagulation and discharge on clopidogrel. Patients without restoration of pulses following knee reduction should go directly to the operating room for exploration with or without intraoperative angiography based on surgeon preference. Full-dose heparin anticoagulation should be continued.

Traditionally, knee dislocation after high-energy trauma has been associated with the highest rates of popliteal vascular injury, with a reported incidence of 7% to 40%. There are now increasing reports of low-energy knee dislocation in obese patients (often following a slip or fall from level ground) resulting in even higher rates of associated vascular and nerve injury. Obese patients with seemingly innocuous trauma may be overlooked and triaged inappropriately, leading to delay to diagnosis of limb-threatening ischemia. In the setting of delayed diagnosis (greater than 6 hours) or if the surgeon has high suspicion for severe muscle necrosis intraoperatively, consent for primary amputation should be obtained preoperatively. Although tibial nerve injury is more common in obese patients with knee dislocation than in nonobese patients, nerve disruption is rare (Table 1).

Surgical Approach

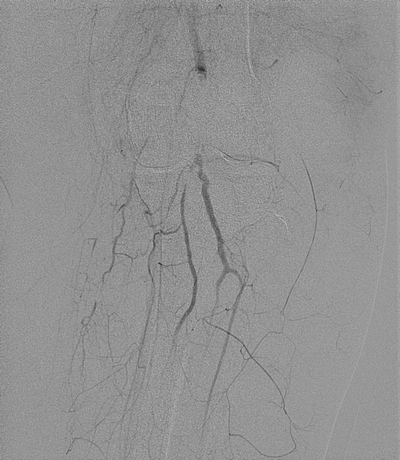

The patient should be placed supine on a radiolucent table and after the induction of general anesthesia, both lower extremities prepped from groin to toes in anticipation of contralateral saphenous vein harvest. The knee should be closed reduced, if this could not be accomplished preoperatively, in conjunction with the orthopedic surgery team. Assessment of knee stability is important after reduction, as gross instability is common after dislocation and usually necessitates placement of spanning external fixation. Placement of an external fixator prior to definitive vascular repair, however, delays revascularization and prevents knee flexion, which is critical to exposure and repair of the injured segment. If pulses return following operative reduction, intraoperative angiography can be performed to rule out a popliteal injury (Fig. 2). Patients with persistent ischemia or an angiographically defined major injury after reduction require popliteal exploration. If warm ischemia time is greater than 5 to 6 hours, we recommend four compartment fasciotomies of the leg through liberal medial and lateral incisions and notation of muscular contractility.

FIGURE 2 Intraoperative angiogram demonstrating popliteal artery occlusion with an aberrant (high) origin of the posterior tibial artery.