Pleuropulmonary Amebiasis

Mohan Verghese

Rajeev Kapoor

Forrest C. Eggleston

Pleuropulmonary amebiasis is almost invariably the result of perforation of an amebic liver abscess through the diaphragm. It accounts for 10% of all deaths from amebiasis. To understand its management, the nature of amebiasis and of the liver abscess it produces must be understood.

Amebiasis

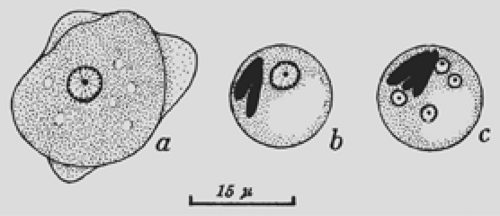

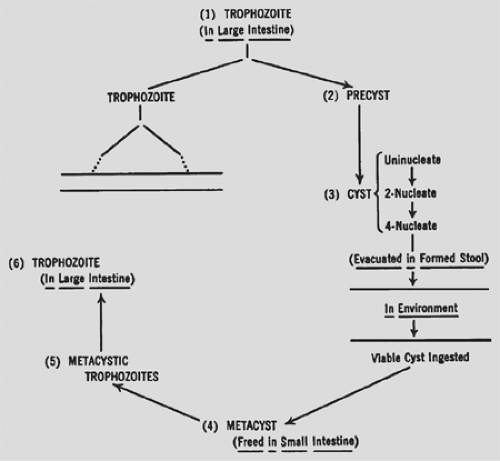

Amebiasis is caused by the protozoan Entamoeba histolytica. The ameba’s life cycle has three stages: trophozoite, precyst, and cyst (Fig. 93-1). Infection results from the ingestion of cysts, usually from contaminated food or water. Excystation occurs in the lower ileum. The resulting trophozoites are the active and growing stage of the parasite. Multiplication is by binary fission. The trophozoites can invade the mucosa of the bowel. Invasion is probably the result of physical means combined with production of the lytic substances from which the parasite derives its descriptive name. If the trophozoites do not invade the bowel, they become precysts and then cysts, finally being eliminated in the stool (Fig. 93-2).

Intestinal amebiasis may be acute or chronic. The acute form produces cramping abdominal pain, diarrhea, and tenesmus. The stool frequently contains blood. The chronic form may persist for a long time, with alternating bouts of diarrhea and constipation. However, a history of gastrointestinal symptoms may not be forthcoming in many patients who develop amebic liver abscess.

Amebic Liver Abscess

When amebae invade the colonic mucosa, particularly in the cecum, they may be carried to the liver through the portal venous system, where they lodge in the venules, producing thrombosis, followed by an infarct, necrosis of liver tissue, and a localized abscess. This is not an abscess in the classic sense but rather a collection of necrotic liver tissue with white blood cells and amebae. The amebae in the periphery multiply, releasing lytic enzymes and resulting in additional necrosis and enlargement of the abscess. No fibrous capsule or clear margin exists between the abscess and the surrounding tissue. Although the parasite does not normally stimulate an intense inflammatory response, like other infective agents, it may do so under certain conditions, particularly if there is secondary infection.

Right lobe liver abscess is more common than the left lobe abscess, the incidence being 55% to 85%.6 Multiple abscesses are present to the tune of 27%.6 Although these abscesses may occur at any age, they are most frequent in the third to fifth decades of life. In adults, men are infected seven to nine times as often as women; in children, no gender difference is noted.

Symptoms of an amebic liver abscess may be present for a few days to many weeks before the patient seeks help. In the experience of one of us (F.C.E.) and associates,1 the average duration was 33 days. Symptoms vary; as a result, the diagnosis is not clear in one-third of cases.2

Pain in the right upper quadrant with or without fever is the most common presentation. Anorexia and malaise are usual, and patients whose treatment has been delayed may have experienced profound weight loss. Blood in the stool is noted in only about 25% of patients. Many patients present with tender hepatomegaly. Softening suggests imminent rupture of the amebic liver abscess. In addition, intercostal pressure reveals tenderness. Pleural effusion is common. Jaundice is uncommon; when present, it is associated with a poor prognosis.

Leukocytosis (WBCs 12,000 to 30,000/mm3) is the rule. Liver function tests show moderate elevation of alkaline phosphatase, bilirubin, and transaminases. Serologic tests, if positive, suggest current or previous invasive amebiasis. The enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) is highly sensitive, is easily available, and can be completed in about 35 minutes. The test may be negative in the first week; the titer may peak in 3 months and decrease to lower but detectable levels in 9 months. This test may not be very useful in endemic areas, where widespread colonic invasion of ameba results in high titers without hepatic involvement. In these areas, its value remains in differentiating amebic from pyogenic liver abscess and other cystic lesions of the liver.7,12 Liu and colleagues9 have described the usefulness of the polymerase chain reaction (PCR) in confirming the diagnosis of amebiasis by amplification of 16S ribosomal RNA.9

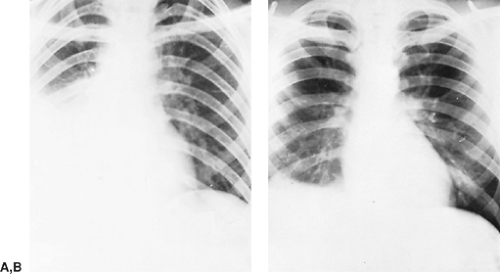

Chest radiography usually shows an elevated diaphragm, often accompanied by a pleural effusion (Fig. 93-3). Computed tomography (CT) (Fig. 93-4), ultrasonography (Fig. 93-5), magnetic resonance imaging (MRI), and isotopic imaging all demonstrate both the presence and site of liver abscesses. However, in the acute situation, CT, MRI, and isotope imaging are not any better than ultrasonography. Ultrasound is inexpensive, easy to perform, and has a diagnostic accuracy of 90%. Ultrasound is the best investigation for following the size of the abscess on treatment.

When aspirated, the pus is usually reddish brown or chocolate-brown, the so-called anchovy sauce, although initially it may be yellowish or even white. Unless the amebic liver abscess was aspirated previously, it is bacteriologically sterile. Amebae can be demonstrated in approximately half of the abscesses.

Because of the lytic nature of the parasite and the lack of encapsulation of amebic liver abscesses, rupture occurs in 10% to 30% of patients. The usual anatomic location of amebic liver abscesses makes upward or transdiaphragmatic rupture more frequent than infradiaphragmatic rupture (Fig. 93-6).

Thoracic Amebiasis

In amebiasis, 70% to 97% of thoracic complications result from extension of an amebic liver abscess through the diaphragm. The type of complication depends on whether the pleural space, lung, or pericardium is involved, either singly or in combination. Here, only pleural and pulmonary involvement are considered.

Most patients have clinical features of an amebic liver abscess in addition to those related to the thoracic complication.

Pleural Involvement

An amebic liver abscess adjacent to the diaphragm may produce diaphragmatic irritation and a sympathetic pleural effusion. On chest radiography, the diaphragm is elevated and fixed. The costophrenic angle is obliterated. The incidence of sympathetic pleural effusion can be as high as 34% in patients with amebic liver abscess.6 Thoracentesis shows that the fluid is clear or serosanguineous, and it is sterile on culture. Amebae are not present. Such pleural effusion requires no specific therapy other than that for the causative liver abscess. Should it increase, however, it may presage the rupture of the abscess through the diaphragm and the development of frank empyema. Basal pneumonitis and atelectasis, alone or in combination, are the other complications of an unruptured liver abscess. Some 10% of our patients had basal pneumonitis or atelectasis; 22% with unruptured amebic liver abscess had pleural effusion, pneumonitis, or both.

Figure 93-2. Life cycle of Entamoeba histolytica. (Modified from Faust EC, Russell PE. Clinical Parasitology, 7th ed. Philadelphia: Lea & Febiger, 1964.) |

Figure 93-3. Simple irritative pleuritis with effusion in the right hemithorax. A: Before treatment. B: After treatment. |

Figure 93-4. CT scan showing a large abscess in the right lobe of the liver.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree

Get Clinical Tree app for offline access

Get Clinical Tree app for offline access

|