Peter Libby was born in Berkeley, California, on February 13, 1947, and grew up in that city as well. He graduated in 1969 from the University of California (UC), Berkeley with a bachelor’s degree in biochemistry and French literature, and earned his medical degree in 1973 from UC, San Diego. He trained in internal medicine and in cardiovascular diseases at the Peter Bent Brigham Hospital (now Brigham and Women’s Hospital [BWH]) in Boston. During medical school, he was active in research, and continued this during his residency and fellowship. After completing a clinical/research fellowship in medicine, he became an assistant professor of medicine at Tufts University School of Medicine, and established a basic cardiovascular research laboratory there. Just as he was being promoted to full professor of medicine and physiology at Tufts in 1990, he was asked to return to BWH—and did—as director of the vascular medicine and atherosclerosis unit of the cardiovascular division in the department of medicine. In 1998, he became chief of cardiovascular medicine at BWH, and has remained in that position ever since. His research has flourished during the past 30 years, and he has led the investigation of the relation between atherosclerosis and inflammation—resulting in the publication of >300 articles in peer-reviewed medical journals. He also is an editor of Braunwald ‘s Heart Disease . Dr. Libby is a popular speaker and has been a visiting professor at prominent universities in numerous countries. He and his lovely wife, Beryl Benacerraf—also a full professor at Harvard Medical School—are the parents of 2 very successful children. Moreover, Dr. Libby is a pleasure to be around.

William Clifford Roberts, MD (hereafter Roberts): Dr. Libby, I appreciate the opportunity to talk to you during your visit to Dallas, and I especially appreciate your having this conversation in my home. Could we start by my asking about your parents, siblings, and growing up in Berkeley, California? What was it like ?

Peter Libby, MD (hereafter Libby): I was an “HMO baby,” born at the original Kaiser Permanente Hospital on MacArthur and Broadway in Oakland, California. My parents lived in postwar temporary veterans’ housing in the Berkeley flatlands at that time. My father, who had come back from the European theater in 1945, got together with some of his former college buddies from the student cooperative and they, in the spirit of cooperative society, bought an acre of land bordering Charles Lee Tilden Park, influenced by Frederick Law Olmsted, in the Berkeley Hills. Today, I live along the Emerald Necklace, a park system in Boston, designed by Olmsted—a satisfying symmetry. My father and his friends built 4 houses on the single acre, despite the postwar dearth of building materials. They called the private road Rochdale Way, an allusion to the principles of the cooperative movement. My father, Henry Libby, was a chemist.

Roberts: When was he born?

Libby: August 1, 1918. He started graduate work in nutrition at UC, Berkeley. The cutting edge in biochemistry in those days was vitamins and intermediary metabolism. He had just started his graduate studies when he got drafted into World War II. After the war he met my mother, Vivian Green ( Figure 1 ). They had a rapid courtship. She was the cousin of one of his close buddies and was a vivacious and attractive young lady. Over some parental objections, and somewhat rebelliously, they got married rather quickly. I was the firstborn ( Figure 2 ). I have a sister, Susan Carol Libby. We were a happy young family in a typical 1950s household, with a working father and stay-at-home mother. In the polio epidemic of 1952, my mom and I got polio. I made it home, but she didn’t, leaving my father a widower with 2 young kids.

Roberts: Susan was born when?

Libby: September 22, 1949. My father, the unwitting single dad, was helped out by the “cooperative spirit” of his college neighbors. There was a cooperative nursery school. The wife of the couple next door—longtime friends of my father’s from the student co-op dorm, Barrington Hall—helped take care of us. My mother’s cousin Mitzi Raas had introduced my parents, and was also a surrogate mom. She took my sister and me to their house in Bakersfield, California for a while that first summer, when my dad was dealing with the loss of my mom. I’m sure my dad struggled mightily initially. He had become, however, a very eligible bachelor, and many friends tried to set him up. In fairly short order, he met and married my stepmother, Charlotte Lipson. Her first husband had died in the Navy during World War II, and she had 2 kids from her previous marriage. We became, in the grand California tradition, a “blended family.” Charlotte’s family was very prosperous. She had built a house in the Berkeley Hills that was nicer than the one my father had built when wood was still being rationed after World War II. We moved in with them.

Roberts: Were the other stepsiblings about the same age?

Libby: I was almost the same age as the younger child, Karen Adele. My older brother is Gordon Joseph.

Roberts: How long did your mother have polio before she died?

Libby: Just a matter of days. I was hospitalized for 3 days in a communicable isolation hospital in Martinez, California. (Polio, as you know, has been eradicated with the introduction of the Salk and Sabin vaccines, but too late for my generation. This advance of medical science, as it touched me personally, may have added to my vocation to become a physician-investigator.)

Roberts: Did you recover fully ?

Libby: No. I’m told that I have some residual weaknesses from polio. I was a late-bloomer athlete. I learned how to compensate with physical therapy. To this day, I do strengthening exercises. Polio leaves one with various asymmetries and compensations, and these strange mixtures of muscle weaknesses were not obvious until I started to have problems running in middle life. Very smart physical therapists, for whom I have enormous respect, were able to pinpoint asymmetries, and gave me exercises that allowed me to keep running to this day.

Roberts: You were in the hospital only 3 days?

Libby: Yes. I remember vividly getting a spinal tap at the Kaiser hospital. A doctor told me to curl up like a monkey. My maternal grandmother was with me, and my mother was already hospitalized. They took away my stuffed animal that was my mascot because they thought it was contaminated. I was very upset about losing my mascot. It didn’t quite sink in immediately that I also had lost my mother.

Roberts: How old were you?

Libby: Four or 5 years old.

Roberts: Is polio more severe the younger you are?

Libby: I don’t know.

Roberts: How devastating to lose your mother so early .

Libby: It was a matter of days. She died of paralysis of the respiratory muscles. There was nothing they could do then. I think I was a bit rambunctious as a child. I was a handful for my stepmother, trying to find my way in the stepfamily. Probably, having been the alpha child as the firstborn male and all of a sudden finding myself in the middle of a blended cohort didn’t agree with me.

Roberts: Gordon was how much older than you?

Libby: Gordon was a couple of years older than me. Karen was only 6 months older than me. Susan has always been composed, well behaved, and was the best student in the family. Now, she’s the chief executive officer of the family business. I took the rocky road and caused problems with my teachers and my parents.

Roberts: What do you mean by “caused problems”?

Libby: My stepmother was extremely bright. My father was, too. They treated us like adults intellectually. The level of the dinner table conversation was rather high, and I took to it. I was a voracious reader early on, and very comfortable with adult company. I think I was less mature emotionally, perhaps with some trauma from my mother’s death and being inserted into the blended family. I had behavior problems.

Roberts: Did you have memories of your biological mother at all?

Libby: Yes.

Roberts: What did you like to read as a youngster?

Libby: I read the kids’ books, the Oz books, the Landmark books, which were diluted history books. I still like historical novels. I would actually break my curfew by hiding under my covers and reading late into the night by flashlight. I was motoring ahead intellectually but still immature emotionally.

Roberts: Did you read fast from the beginning? You could devour a book very rapidly?

Libby: Yes.

Roberts: How many books were you reading a week at that time would you say?

Libby: I don’t remember. I probably read recreationally when I was supposed to be studying schoolbooks.

Roberts: Were there a lot of books around the house?

Libby: Yes. My parents chose to live in the Berkeley Hills because they were both academically inclined. Among the students in the grammar school I attended, many were children of UC professors.

Roberts: Did your stepmother work outside the home?

Libby: Yes. She was a real estate broker. She was politically active also. In the early 1950s, there was a political movement trying to ferret out un-American individuals. The Army–McCarthy hearings were going on in Washington, D.C. The California version of the House Un-American Activities Committee was the “Yorty Committee.” My stepmother was photographed at meetings that were considered subversive. She was denounced for her left-wing sympathies to the Yorty Committee. She recounted that she was able to beat the rap by acting ditzy and convincing the investigators for the State Un-American Activities Committee that she attended these activities just because she was boy-crazy. In fact, both my parents were quite progressive, and came from the lineage of “the old lefties.” One reason I don’t have a middle name was because they were anticlerical.

Roberts: After you settled down in the new blended family, how did things go? You said your father started his own business after a while. What was that business ?

Libby: He went into chemical manufacturing, chemical specialties like topical pharmaceuticals. My father really wanted to continue the graduate work that he began before being drafted. As Charlotte’s family had some means, we were supported by Charlotte’s father—a physician in California’s central valley—while my father got a doctorate in pharmaceutical chemistry at UC, San Francisco. This was in 1958. I was at his shoulder the entire time, looking over his biology texts and reading pharmacology books. My father was a product of the College of Chemistry at Berkeley. I was brought up reciting the paraffin series along with the ABCs, and was exposed to medicine through my dad’s studies. I went with him to his laboratory on weekends while he was at UC, San Francisco. Once he finished his graduate studies, he founded a chemical manufacturing firm.

Roberts: What kind of products or drugs did his company produce?

Libby: He made topical pharmaceuticals under contract for the Kaiser Foundation Hospitals and other institutions. He didn’t sell directly, but sold to dealers or responded to requests for proposals. He did private label work. Eventually, the margin on those topical pharmaceuticals and cleaning products for schools and hospitals became rather slim. The margins on cosmetics were much better, and when he switched to producing cosmetics, his company went from a mom-and-pop operation that started almost in a garage to a business with 30+ employees manufacturing primarily topical pharmaceuticals and specialty cosmetics.

Roberts: Was your father gone a lot? Was he home at dinnertime?

Libby: He was home at dinnertime. But he worked very hard, leaving early in the morning and working 7 days a week. He read at night.

Roberts: How far was the business from home?

Libby: Very close—we lived in Berkeley, and the business was in the same town. He believed a Berkeley address was important for his business.

Roberts: What would a dinner conversation be like?

Libby: There would be roundtable questions. They would pitch questions to all of us. My stepmother, as I mentioned, was very politically active. She was in the League of Women Voters. I went door-to-door passing out pamphlets with her. Berkeley is referred to as the “People’s Republic” still today. As I was growing up, the “beat movement” was in full swing in San Francisco. Of course, my cohort formed the follow-on “hippie” generation. I was steeped in the ethos of the Berkeley political sensitivities from early on.

Roberts: Did all 4 children get along well?

Libby: We were very different. My brother Gordon, for whom I have great affection, was a natural athlete. He had a natural sense of humor and was very gregarious. I was the nerd, the bookish kid, a bit awkward socially with peers if not adults, and quite nonathletic, perhaps related to some of the residuals of polio. Karen was very social and attractive, but not intellectually inclined. Susan was the good girl and good student. She and I see each other seldom, but are quite close when connected.

Roberts: Did you and your father get along well?

Libby: Yes. There were some periods of tension with adolescent and early-20s angst and separation, but before that, we were very close. I went to work with him and spent weekends at his laboratory, doing my homework there, and working as a technician at his side. I read the pharmacology text by Goodman and Gilman in his laboratory, when it was still a dual-authored book.

Roberts: Your father continued in the laboratory even though he had 30 employees?

Libby: He was the chemist. All product development for the first 5 years or so was by my dad and me. He would write out formulas for me to compound and I would compound them and then we would do stability testing. I mixed and weighed compounds and did assays. We compounded sodium fluoride for dental applications. I did the assays for the fluoride for quality control. I did titrations of various reagents. In the 1960s, white Levi’s jeans were in style for high school kids. Mine had little acid burns on them because I was pouring concentrated sulfuric acid into graduated cylinders, and sometimes the chemicals would splash. I’m sure the kind of work I was doing then couldn’t be done today without goggles and protective gear, with all kinds of OSHA (Occupational Safety and Health Administration) regulations. Young scientists today purchase kits for everything, and don’t have the “joy” of mixing their own reagents as we did.

Roberts: How much time were you able to spend in your father’s laboratory during junior high and high school?

Libby: Most days after school, I would walk to the laboratory and do my homework there, and ride home with him.

Roberts: What did your sisters do while you were at the laboratory?

Libby: Everyone else was more normal. They did more usual after-school activities.

Roberts: What about your stepmother? Did you get along well with her?

Libby: Obviously, integrating into a blended family had its challenges. I was a behavior problem, so we had some tense moments through the years; but many years later, I was the one who looked after her, as the physician in the family. She had bad deforming rheumatoid arthritis with multiple complications, including pericarditis and rheumatoid lung disease. I often flew to San Francisco when she was ill. She made my father very happy.

Roberts: I presume neither parent is alive?

Libby: Correct.

Roberts: When did your father die?

Libby: In October 2008. He was living independently and still working every day at age 89.

Roberts: What about your mother?

Libby: She had atrial fibrillation, had a stroke, and multifactorial respiratory disease, and died in 2004.

Roberts: What were your father’s experiences in World War II?

Libby: There was a reason they called his “the greatest generation.” They had a mission. There was no ambiguity about the enemy or about serving in the armed services. My father was in North Africa and had to learn how to shoot a gun. He was part of one of the landings in Italy. He was wounded by some shrapnel. He always said that he was destined to be a survivor, and he indeed made it back. Clearly, it was a formative experience. He had graduated from college right before being drafted. Because he was a chemist, he was a lieutenant in the chemical corps in the army. At the age of 21, because he had a college degree, he was given a clipboard and told to oversee the loading of a ship, and during combat to take on other leadership responsibilities that people his age normally did not experience.

Roberts: When you were in school, did you participate in activities other than your studies ?

Libby: The formative extracurricular activity for me was music. I was very musical, and my stepmother was an excellent pianist. We had the old 78s of the Beethoven symphonies and other classics. My teachers saw that I had a spark for music. They suggested that I audition for the San Francisco Boys Chorus. I went and auditioned, and was accepted, probably not because I had a great voice, but I had great enthusiasm, and perhaps some feeling for the music. The chorus was tiered—a training group, followed by a concert group, and ultimately, an ensemble group. I worked my way up all those tiers.

Roberts: How old were you when you auditioned?

Libby: I was 10 or 11 in 1958. From then until my voice changed in 1962, singing was the dominant extracurricular activity for me. We were the chorus for the San Francisco Opera. Imagine what it was like for a kid to be involved with 2 opera companies—San Francisco Opera, and what was then called the Cosmopolitan Opera. I would go backstage, don my costume, get my makeup, and wait in the wings for my part. We rehearsed several times a week.

Roberts: How many operas did you participate in?

Libby: Many. There was a music camp every summer for 1 month. I was totally immersed in music.

Roberts: Two or 3 times each week after school, you went to San Francisco to rehearse?

Libby: Yes. The leader of the chorus, Madi Bacon, lived in Berkeley Hills. I didn’t always go to San Francisco. When I was in the ensemble group, we would often rehearse in her home, which was walking distance from my house. She was quite a character, and an important mentor for me.

Roberts: How many were in the entire boys choir?

Libby: Probably 50 or 60 boys. The concert group was about 20 to 24, and the ensemble group was 8 to 10. Madi Bacon had earned her master’s degree in Elizabethan music at the University of Chicago, I believe. The ensemble took on some very technically demanding pieces under her, such as the madrigals of Thomas Morley and of Thomas Weelkes. I found a home in this environment.

Roberts: Did you play an instrument?

Libby: I studied piano and the baroque flute. In high school, I had a great time in chamber music. In the 1970s, before I had children, I played a lot of recorder chamber music with my mother-in-law, who was a gifted harpsichordist. There is no room in my life for performance now, but I have my beautiful instruments, and maybe someday I’ll come back to them.

Roberts: What about singing now?

Libby: I sing only in the shower now, and alone in the car, for the good of humanity.

Roberts: Were there other teachers in school who had a major impact on you?

Libby: Max Knight, the father of one of my classmates, did. The Knight family lived a few blocks away. Mr. Knight was a refugee from Austria, and although trained in law, he was an editor at the UC Press. He was an avid translator, and he took his son and me under his wing and gave us German lessons in his home. He used I.F. Stone ‘s Weekly (a leftist newsletter) as a jumping-off point for a weekly political “seminar.”

I made my first trip to Europe at the age of 16, first arriving in Zurich and then traveling to Lucerne and Interlaken. I met up with my classmate—Max Knight’s son—at a boarding school near there. We went on a bus tour through Yugoslavia, and it was quite an experience. We had both studied Latin and were interested in classic antiquities. We took off with our rucksacks. I had $300 in $10 travelers’ cheques, and stayed at youth hostels that cost only 50¢ a night—so $300 went a long way. We backpacked around Italy, took a boat to Greece, and toured that country. We took a small plane to Crete to visit the archeological sites. I drank too much retsina in a taverna, and had my first hangover. We visited Paris on the way home. It was an incredible experience to bum around Europe at age 16 on my own.

Roberts: How many languages do you speak now?

Libby: I speak French fluently, Portuguese and Italian fairly well enough to make myself understood, medical Spanish, and I can communicate basic needs in German. I learned Italian to speak with my wife’s friends in Italy, where she lived for a while. Italian, of course, is the language of opera.

Roberts: Your studies, I presume, were easy for you?

Libby: I did not have any problems learning, but I was not the apple of the teacher’s eye. The studies themselves were not a huge difficulty for me. Being “a good boy” was more of a challenge.

Roberts: You decided to stay at Berkeley for college?

Libby: By the time I was in high school, I had matured emotionally. I was much more integrated into the social fabric by then, and had classmates who also were bookworms—I had friends and a network. When Sputnik was launched, it put the nation into an uproar that we were losing ground technologically to the Soviets. There was a great investment in science education after that. Berkeley High School initiated pilot programs for biology and chemistry and new secondary education courses. The chemistry course was written by professors in chemistry at UC, Berkeley. I had incredible science exposure in high school; the high-school teachers usually had master’s degrees, and the curriculum used new, high-level, and experimental books that were still in paperback drafts at this time. When I got to UC, Berkeley as a freshman, I had already done college-level chemistry and biology. That advantage enabled me to immerse myself in the ferment of the 1960s student rebellions without paying too high a price academically. College was generally very easy for me.

Roberts: Did you consider another college besides Berkeley?

Libby: No, but my father strongly encouraged me to consider other colleges. I think he thought it would be good for me to get away from home, and the alma mater of both my parents. He went to a scientific meeting at UCLA when I was a senior in high school. (We drove in our Studebaker Lark that could barely go 65 miles an hour.) While he was at the meeting during the day, I roamed around the UCLA Westwood Campus. He made me check out both UCLA and UC, Santa Barbara. He tried to sell me on other campuses, but I remained determined to go to UC, Berkeley.

UC, Berkeley was only a few blocks from my high school. I was immersed in the Berkeley environment. When President Kennedy, Eleanor Roosevelt, and Robert Oppenheimer came to the Berkeley Campus, I was there—I heard these famous individuals speak. In college, I lived in the same cooperative dormitory that my dad had lived in. (Barrington Hall has since been shut down, I think.)

Roberts: Where did your stepmother go to college?

Libby: She had been sent by her strict physician father to a Dominican convent school in Marin County because of some teenage peccadilloes, and she finished high school at the convent. Then, she went to UC, Berkeley. She was quite a rebel herself.

Roberts: When did you decide that you wanted to be a physician?

Libby: At college I majored in the humanities (French literature) and biochemistry. I spent my junior year (1966 to 1967) in Bordeaux, France. I tried to do some pre-med courses there, but they were terrible. I thought I’d be much better off there steeped in the humanities. I came back to Berkeley, fluent in French, with a good grounding in French and comparative literature. I still needed to do some pre-med courses and did a “double major” in biochemistry and French.

Roberts: When you say humanities, French comes under that?

Libby: As a freshman I declared my major as humanities, but I focused on French literature. I matriculated in 1964, a time that was ground zero for the student protest movement in Berkeley. The Civil Rights Movement had been going on for a few years. I was on all the picket lines, fighting for civil rights. My freshman year was the Free Speech Movement, the first of the student protests of the 1960s. The seminal event was the sit-in at Sproul Hall, the administration building of UC, Berkeley. I sat in at Sproul Hall, where I shared Joan Baez’s peanut brittle. We had Vietnam Day when I came back from Bordeaux in 1967. Then, there was the People’s Park, where UC, Berkeley wanted to build a dorm and take some green space away. We had “bulldozer alerts” and would protest the razing of the park. While I was engaged in research work as part of my biochemistry studies (plating bacteria for bacteriophage experiments), I had to walk through tear gas outside to get to the laboratory. I thought that maybe I had had enough of Berkeley at that point. The department of biochemistry had its own building and very select students. The biochemistry faculty took incredible care of its students, and they were very concerned that we find the right places for our graduate work. Although I was destined toward medicine, they encouraged me to go to graduate school in biochemistry, rather than medical school. They regarded medicine as a trade, not a science like biochemistry. One adviser told me that if I really had to go into medicine, I should go to Harvard. They took loving care of us. Within the interstices of this huge university of almost 30,000 students, I got individual attention. I became a maestro at working the system at Berkeley in this regard.

Roberts: What do you mean by “working the system”?

Libby: One had to pick the courses, pick the professors, avail oneself of office hours, and take the small seminars. I had a great time at Berkeley in both my majors. Biochemistry was extremely rigorous; I use the chemical grounding that I got there (and from my father) every day in my work now. I audited the organic chemistry course for pre-med students while I was taking inorganic freshman chemistry—mainly because of Melvin Calvin, who taught the course (Calvin won the Nobel Prize for discovering the mechanism of photosynthesis). This course was very easy for me because of what I had learned in my dad’s laboratory and my high school chemistry course. I later did the formal organic chemistry course for chemistry and chemical engineering majors, as opposed to the watered-down pre-med course. In retrospect, it is useless for pre-med students to study synthetic organic chemistry, but it was problem solving, and I enjoyed the discipline.

Roberts: What kind of chemist would you call your father?

Libby: He was a pharmaceutical chemist.

Roberts: You decided to go to medical school, and it disappointed some of your professors that you weren’t going to stay directly in chemistry.

Libby: Yes. The biochemistry department wanted biochemists. They viewed their students selecting medicine as a career with skepticism and disappointment.

Roberts: How did you decide that you wanted to be a physician, and how did you decide to go to UC, San Diego for medical school?

Libby: My stepmother’s father was a physician. He had wanted my father to move to the Central Valley area to set up a pharmacy, but my dad wanted to stay in Berkeley. This grandfather was a rock of support while we kids were growing up, but he also was very controlling and demanding. He was an outstanding businessman. He saw the Great Depression coming, and shifted to a very strong cash position before the crash of 1929. According to my stepmother, he stockpiled cash and staple goods, and when the Depression hit and properties were auctioned off to pay tax liens, he jumped in and acquired quite a bit of real estate at low prices.

Roberts: What was his name?

Libby: Isadore Max Lipson (died 1960). He also had a working ranch in Tulare County. He not only built the medical clinic, which he ran with an iron hand, but he also raised horses. He built irrigation ditches for the oak trees, an apparent eccentricity to the other ranchers, who cleared their land for grazing and cultivation. As the town grew, his property—now part of the suburbs—was the most valuable because of the shade trees. Everyone wanted to buy his land. A street where his former ranch had been was named after him.

Roberts: That was how far from Berkeley?

Libby: In those days, it was an overnight drive—we would drive at night because it was so hot during the day. Cars didn’t have air conditioning. The Central Valley was a 5- to 6-hour ride. Lipson was a role model. One of the decisive lessons I learned from him was that you have a great deal of freedom as a professional. My stepmother had rheumatoid pericarditis during World War II, while at Fort Defiance, Arizona. Gas was rationed during that time. He went to the rationing board and demanded coupons for gas to be able to visit his daughter, threatening that he would quit practicing if they did not deliver. They gave him the coupons.

UC, San Diego’s medical school was brand new. I had been steeped in UC, San Francisco, where my dad got his doctorate, which then had a classical Flexnerian curriculum. It was very staid, preordained. UC, Davis was new, but I had a disastrous interview there. I told the interviewer that I wanted to do research, and he advised that I should get a PhD. I was asked why I wanted to go to medical school if I wanted to do research. I was almost in tears driving home. I withdrew my application. UC, San Diego had an innovative curriculum, with math and science as well as medicine. It was a very strong science campus. I went for an interview and was totally enchanted with the campus environment. Everything was new. The medical school was an enormous investment in science and technology, put together in the wake of the Sputnik launch. The state government under Governor Edmund (Pat) Brown (the father of the current governor) and the regents of the university poured state money beyond the federal dollars into the San Diego campus. It was a no-brainer for me to choose UC, San Diego. I was overjoyed when I was accepted, because I thought it was a perfect fit. (I had been brought up to believe that anything south of the Tehachapi Mountain range in California was “heathen.”)

Roberts: When did you begin medical school?

Libby: 1969. On day 1 of medical school, a Saturday morning introduction to the clinic, Dr. Eugene Braunwald presented a patient with rheumatic heart disease. Dr. Braunwald, the founding chief of medicine there, had brought a core of individuals from the National Institutes of Health. From that day on, I knew what I wanted to do. My fate was sealed. I still meet with Dr. Braunwald often, and I still learn from every encounter. He’s my scientific and medical father. I think many people share that paternity.

Roberts: Were there any surprises in medical school? How many classmates did you have there?

Libby: It was a tiny medical school, with <50 students in the charter class that preceded me. My class, the second class, had about 48 students. We had the entire faculty at our beck and call. I don’t think I’ve ever worked harder, and it was immensely fun and productive.

Roberts: I gather you graduated number 1 in your class?

Libby: I don’t think they had rankings, we didn’t have grades. California is like the fictional Lake Woebegone, where “all the children are above average.”

Roberts: You worked hard because you loved it so much.

Libby: Yes. It was an unbelievable opportunity. Teachers were stars, and we got individual attention. As a new medical school, they were keen on making a mark, and they wanted us to ace the national board examinations. Indeed, the charter class got the top score in the nation, and my class did too.

Roberts: That was after 2 years?

Libby: Yes. In the freshman year, we had laboratory rotations just like in graduate school. I worked on isolating thymidylate synthase with Dr. Morris Friedkin, who was later elected to the National Academy of Sciences, from cells we got from Renato Dulbecco, who became a Nobel laureate. My adviser was Dr. Daniel Steinberg, a lipid biochemist, who also became a member of the National Academy. I learned cell culture by being a rather pushy guest in the laboratory of Dr. Gordon Sato, a pioneer in this area. When I was a junior I went to Africa with support I finagled from Dr. John West, a legendary pulmonary physiologist, to work in a Nigerian hospital.

Roberts: When you first entered medical school, were there any surprises? Obviously that first day was a glorious surprise, but were there other surprises after, with studies, colleagues, or faculty?

Libby: I was surprised by how much I enjoyed pediatrics and obstetrics. I loved being with kids, and I had a great time delivering babies at the naval hospital in San Diego. It was great fun because it was just me and a rotating intern taking care of the entire obstetrics floor. We would take turns being the anesthesiologist and the obstetrician. I was a beginning fourth-year medical student, and had no idea how much trouble I could have gotten into. I gave spinal anesthetics to pregnant women with no idea of how risky that could be. There was a resident that we could call if we did get into trouble. My last delivery was a footling breach twin delivery, and we did call the resident for that one. This was before ultrasound, and the twin pregnancy was a surprise to the mom, and the breech presentation was a surprise to me.

Roberts: Did you enjoy your rotation in surgery?

Libby: I was performing animal surgery regularly because our major experimental preparation in those days was in dogs. I worked under the supervision of Jim Covell, one of Dr. Braunwald’s associates, and Dr. Peter Maroko, who was then a postdoctoral fellow in Dr. Braunwald’s and Jim Covell’s laboratory. I was very keen on surgical technique, and wasn’t half bad at it at the time, but I was never drawn to a career in surgery.

Roberts: How did you get into research? How did that first come about at medical school?

Libby: I felt destined for research from my undergraduate days. The department of biochemistry at UC, Berkeley was very research-oriented. The faculty took good care of their students. It was a foregone conclusion that the biochemistry majors would be doing research as biochemistry graduate students. I had terrific, inspiring teachers, and did laboratory rotations as an undergraduate. I knew I was bound for the laboratory. Perhaps that was an extension of the experience I had working in my father’s laboratory.

Roberts: How did your research in medical school first come about? Did you go to Dr. Braunwald’s office or Jim Covell’s? What happened?

Libby: My first research rotation was with Dr. Morris Friedkin, looking at the regulation of thymidylate synthase in cultured cells. Then, in the cardiovascular section of our organ physiology-pharmacology course, the late Peter Maroko—then a teaching assistant—saw my enthusiasm for the topic, and suggested that I come by the laboratory and watch an experiment with coronary occlusion in the dog laboratory. I was sucked right in.

Roberts: You had quite a few publications in medical school. How much time did you spend in the research laboratory during medical school?

Libby: I spent a tremendous amount of time in the laboratory doing research, and in the hospital’s coronary care unit, doing ST-segment mapping in patients with acute myocardial infarction. I neglected my regular curriculum to spend more time in the laboratory. UC, San Diego was proud of having an innovative curriculum, and it had a pass–fail system. To this day I don’t know as much anatomy as I should, because instead of spending my time memorizing muscles and bones, I did experiments. I worked really hard as a medical student, and enjoyed it tremendously. Moreover, I had a conscious appreciation, even as a 20-something, that I was incredibly privileged, and was at just the right place at the right time to have a fantastic opportunity and experience.

Roberts: Once you got into the cardiovascular laboratory, you spent more time in the laboratory than in the classes or studying. You took advantage of the fact that you didn’t have to go to all the classes.

Libby: Yes. I spent maximum time in the laboratory. The faculty, to their credit, looked the other way as I focused on investigative work rather than the core curriculum.

Roberts: After you had been at San Diego a few days, you were very pleased with your medical school choice ?

Libby: Yes, I was overjoyed. I had been brought up in the shadow of the UC, San Francisco School of Medicine. My father had been on the faculty of the school pharmacy there. UC, San Francisco had a very traditional Flexnerian curriculum, whereas the medical school in San Diego had an innovative curriculum focused on science and research. I took to it like a duck to water. I entered medical school in 1969, so it was the end of the buttoned-down era and the beginning of the time of student unrest.

Roberts: How did you decide on your internship?

Libby: When I was a junior medical student in 1972, Dr. Braunwald was recruited to Harvard Medical School and the Peter Bent Brigham Hospital (now BWH) to be the physician in chief. I had heard of the Brigham, and knew that it was a very competitive and elite program. I applied for the internship there, and I think it fit Dr. Braunwald’s plans as well—I had been working in the biochemistry part of his experimental laboratory in San Diego, and he had recruited Dr. Stephen F. Vatner and Dr. Peter Maroko to join him on the Harvard faculty. They needed to set up their laboratory, and I had knowledge and skills in biochemistry. I was selected as an intern, and ended up setting up the biochemistry part of the Maroko/Braunwald laboratory.

Roberts: So Dr. Braunwald was at the Brigham a year before you got there ?

Libby: Yes, but I spent some time at the Brigham during my senior year in medical school. I decided to make my senior year in the European tradition, a bit of a “Wanderjahr” (“travel year”). I had arranged to do a subinternship in neurology at Bowman Gray School of Medicine (now Wake Forest University School of Medicine) in Winston-Salem, North Carolina, because Dr. James F. Toole had been a visiting professor at UC, San Diego, and I connected with him. He was interested in neurovascular disease, and later led one of the major clinical trials of carotid endarterectomy. I spent a month at the North Carolina Baptist Hospital, where I didn’t really fit in very well, but learned a lot. I also spent time in Zaria, a city in northern Nigeria, with Professor David Warrell, then a young faculty member (now an emeritus professor of tropical medicine at the University of Oxford). He had been a postdoctoral fellow at UC, San Diego with John West, and I jumped at the chance to go to Zaria. The trips during my senior year required layovers on the East Coast, and I would go to the Brigham to work with Peter Maroko and order equipment and set things up in the laboratory. I had signed up for a 12-week rotation in pediatrics, but I was enjoying myself in Africa, and I sent a letter to the course director to tell him I would be there for only 8 weeks and not 12, because I was involved in a rotation abroad. I had a lot of cheek as a medical student, but I also squeezed the most opportunities out of the time, and I have no regrets.

I saw things in Nigeria that I had never seen before, and probably will never see again (I hope)—such as severe encephalopathy from rabies, blackwater fever with malaria, tetanus, and the like. During an epidemic of meningitis, we used needles resterilized in what the British called “methylated spirit.” We would light the needles on fire after dipping them in methanol to sterilize them between spinal taps. There were not enough beds for the patients, so we often took care of them on the ground—it was a very rudimentary hospital. I had the agility to do spinal taps on the floor at that age!

Roberts: How long were you in Nigeria?

Libby: One month.

Roberts: Where did you live?

Libby: I lived in a spare room in David Warrell’s flat.

Roberts: What was he doing there?

Libby: He was doing experimental work on parasitology.

Roberts: Were the British gone by then?

Libby: No. It was an independent country, but the British were very much involved in the universities, and the chief of medicine was a rather dour Welshman, Prof. Eldrud Parry.

Roberts: Did you know David Warrell in medical school?

Libby: David Warrell had been a postdoctoral research fellow with John West, the lung physiologist. I was incredibly brazen—I went to West and asked if he could pay for my time in Nigeria, working with Warrell, from his training grant. He worked it out! On the way back from this trip, I stopped off in London and introduced myself to some folks at the Hammersmith Hospital (then a center of cardiovascular disease) as a protégé of Dr. Braunwald (without his permission). I made rounds with Prof. Celia Oakley, and went to their grand rounds (it was a case of endocarditis presenting as stroke). I had no compunction about showing up at places, knocking on doors, and making a pest of myself. The resulting experiences were unforgettable.

Roberts: How much time during your senior year was actually spent in San Diego?

Libby: Probably 7 months.

Roberts: You went to Boston beginning your internship in July 1973. How did Brigham’s department of medicine strike you ?

Libby: San Diego had not been a hotbed of clinical activity, and although the Brigham was much smaller than it is today (it was then a rather “boutique” hospital), the patients were more numerous and sicker than I had generally encountered in San Diego. The quality of my colleagues and teachers was incredible—I had a fantastic experience. My internship class has done well. There was Ed Benz, now president of the Dana-Farber Cancer Institute and formerly the Sir William Osler Professor at the Johns Hopkins University School of Medicine; Christian Raetz, who was the chair of biochemistry at Duke University (he died in August 2011); and Stuart Mushlin, now a master clinician at BWH; among others.

Roberts: Your internship allowed a good deal of time in research?

Libby: Dr. Braunwald established a system of research internships at the Brigham, for a pair of interns to spend 6 months doing the regular internship and junior resident work the following year, and then 6 months in the laboratory. I was in the second group of Dr. Braunwald’s research interns, known informally (perhaps a bit derisively) as “hemi-docs.”

Roberts: The total number of interns was how many?

Libby: I think we were about 12.

Roberts: You were working at that time on how to reduce myocardial ischemia as the major thrust.

Libby: We were working on reducing myocardial infarct size. The prevailing concept then was that myocardial infarction was like a lightning bolt that struck out of the blue. It was considered an all-or-nothing phenomenon until the early 1970s. Myocardial infarction was thought to be like turning off a light switch. Dr. Braunwald had worked on the determinants of myocardial oxygen consumption at the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute. He thought that if one could alter the supply and demand equation, one might be able to mitigate the size of the myocardial infarct. That concept was being tested when I joined his laboratory—that myocardium could be preserved by reducing myocardial requirements or by improving the balance between oxygen supply and demand. That followed very logically from Dr. Braunwald’s earlier investigations of myocardial oxygen consumption.

Roberts: During your internship, did you spend 6 concentrated months in research?

Libby: Yes.

Roberts: And the same thing happened in your first year of residency—you never left a research laboratory from the time you were junior high.

Libby: Yes. I was around test tubes and reagents from junior high school on.

Roberts: So you had 3 years of internal medicine training, but 12 of those 36 months were in a research laboratory?

Libby: The story is a little more complicated than that. First of all, we were trying to enroll patients in clinical trials of pilot studies of limiting myocardial infarct size. Although the Brigham had a busier coronary care unit than the one in San Diego, there were not enough fresh acute myocardial infarction patients to do a clinical trial. Dr. Maroko had attended medical school in São Paulo, Brazil, and he wanted to use his connections there to enroll more patients. Consequently, Dr. Braunwald and Dr. Maroko sent me to do clinical studies of infarct size limitation in São Paulo during my nonclinical months. I didn’t speak much Portuguese, although I had learned some, because Dr. Maroko and I would go to his home to work on manuscripts and data, and he spoke Brazilian Portuguese at home with his family. I also would baby-sit for his children sometimes. He had been born in Poland, and was a refugee during World War II. After a very zigzag course, he ended up in Brazil. I was expected to rent a car and go around from hospital to hospital in São Paulo, enrolling patients in a clinical study—I learned Portuguese that way. Dr. Maroko came with me to begin the study, and he said I needed to rent a car, and I asked how I should do that. He told me to pick up the telephone and rent a car. I said I didn’t speak the language, but he still only said to pick up the telephone and rent the car. He spoke 4 to 5 languages, and didn’t see that I should have a problem. So I did as he said, and learned rudimentary Portuguese while rushing around São Paulo in a café-au-lait–colored VW bug, enrolling patients for this clinical trial, which became the pilot study for MILIS (National Institutes of Health [NIH] Myocardial Infarction Limitation Study).

Roberts: How long were you in Brazil?

Libby: I spent a month of my internship year and a month of my junior residency year there.

Roberts: How many patients did you get for the study from Brazil?

Libby: Dozens. We gave propranolol intravenously to try to reduce myocardial oxygen requirements in the AMI (acute myocardial infarction) patients. In retrospect, what I was doing was pretty risky. We didn’t have hemodynamic monitoring then routinely in Brazil. (Now Brazilian cardiology is very well equipped, world class, but not so in 1973 and 1974.) Because Dr. Braunwald knew Dr. Yevgeny Chazov, he wanted to extend the study to Russia (then the Union of Soviet Socialist Republics), and he wanted me to go there and do the same thing that I had done in Brazil. But I’d only done 12 months of clinical training at that point, and I did not feel sufficiently grounded in basic internal medicine to be a cardiologist. I brazenly told Drs. Braunwald and Maroko that I preferred not to go to Russia, and requested to do a full 12 months of senior residency. What could they do? They couldn’t force me to go to Russia, so I dropped out of the research and did the full 12 months of senior residency—this turned out to be a terrific decision. I fall back on the skills I learned and instincts I developed as an internist in those days every time I go on clinical service today.

Roberts: After that third year of postgraduate training, what happened? That brings us to June 1976.

Libby: I told Dr. Braunwald during my senior residency that I wanted to obtain more training in basic science. I had my undergraduate training in biochemistry, and I wanted to work at a more fundamental level than the experimental myocardial infarction studies. Dr. Braunwald seemed a bit skeptical, but he graciously set up a couple of interviews for me with basic scientists at Harvard Medical School, to help me find the appropriate laboratory in which to do a fellowship. Dr. Braunwald sent me to see Dr. Bert Vallee, a world expert on metalloenzymes, and to the chairman of biochemistry, Eugene Kennedy, who sent me in turn to Alfred L. Goldberg, then a younger faculty member in the department of physiology. Dr. Goldberg was working on intercellular protein breakdown. I thought he was very bright, and his laboratory was very interesting because it spanned bacterial genetics through to integrative physiology. (The idea that protein breakdown was one of the determinants of skeletal muscle mass was how Goldberg got into the field.) I spent 3 years in Dr. Goldberg’s laboratory studying protein breakdown, and got some pretty thorough grounding in protease biochemistry. That built on the exposure to hydrolase biochemistry that was cutting-edge enzyme mechanism work taught by my teachers at Berkeley, such as Dan Koshland. I’m still working on proteases today!

Roberts: You spent 3 years doing basic science research? Did you also do other activities during that time?

Libby: I continued my Friday clinic to see the patients I had followed previously. I had a longitudinal clinic for 6 years. Dr. Braunwald also gave me the opportunity to be the attending physician in the emergency ward, and adjacent short-stay unit (the “holding unit”), for 1 month each year—I did it every December for 3 years. I reviewed the charts of the patients who had been seen by the residents in the emergency department the night before. I made rounds in the short-stay unit early in the morning; then I would go to the laboratory and put in a day’s work there; and at the end of the day, I would do rounds in the short-stay unit again. My rounding was not a money-maker for the department, apparently. Somehow, by the department accounting, I actually generated a deficit, but Dr. Braunwald would graciously waive that deficit.

Roberts: During your 3 years in basic research, who paid you?

Libby: I competed for, and received, an American Heart Association (AHA) fellowship grant. I was the Samuel A. Levine Fellow of the AHA, Massachusetts Affiliate, which meant that I must have received a good score on their grant application. I was very proud to be the Levine fellow, as Sam Levine was not only one of the founders of the specialty of cardiology who was at the Brigham, but also I felt in his lineage as my coronary care unit attending in residency was his successor, Bernard Lown. (I learned a huge amount from Bernard about the approach to the patient, and how to use your personality positively as an intervention with patients, but we often had friendly differences about therapy.) Actually, to this day we call the Brigham coronary care unit the “LCU,” for “Levine cardiac unit.” I also received a National Research Service Award—one of the independent National Research Service Awards. So, as a research fellow I was funded by both the NIH and the AHA.

Roberts: What else happened during those 3 years of basic research?

Libby: I got engaged at the beginning of my senior residency (July) and married on November 22, 1975—37 years ago.

Roberts: Who was the lucky young lady?

Libby: Beryl Benacerraf, but I was the lucky one.

Roberts: You met her when?

Libby: Around April 1, 1975—the first day of her internal medicine clerkship. She was a third-year Harvard medical student.

Roberts: You were on the wards at that time.

Libby: Yes.

Roberts: What attracted you to her?

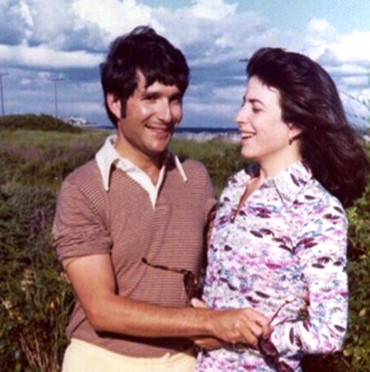

Libby: I had the fantasy when I moved to Boston that I was going to find a Harvard medical student who was slightly brighter than I was, who was gorgeous, musical, and spoke French. Beryl walked into my life, and she met all those criteria except for one. She’s not just slightly smarter than me; she’s much smarter than me ( Figures 3 and 4 ).