Chapter 10 Perioperative Patient Safety

History and Perspective

Patient safety in the health care environment is recognized as less than optimal or desirable. A series of eye-opening reports were published in the 1990s and provided clear evidence of high rates of serious adverse events that resulted in serious harm to hospitalized patients. The Institute of Medicine (IOM), in its landmark report, To Err is Human, published in 1999, estimated that as many as 1 million people/year were injured and up to 98,000 died annually because of medical errors.1 When the focus was specifically turned to surgical patients, surgical care accounted for between 48% and 66% of adverse events among nonpsychiatric hospital discharges.2 In regard to operative procedures and deliveries, 3% resulted in adverse events, and surgical adverse events were associated with a 5.6% mortality rate, accounting for 12.2% of hospital deaths. Furthermore, 54% of surgical adverse events were judged to be preventable.

In 2000, the IOM called for a national effort to reduce medical errors by 50% within 5 years; however, progress has fallen far short of that goal, despite numerous private and public initiatives aimed at finding solutions. Leape and colleagues3 have proposed that these efforts fell short because health care organizations did not undertake the major cultural changes required to accomplish true and lasting improvements in performance. They proposed that health care entities must become “high-reliability organizations” that hold themselves accountable to offer safe andeffective patient-centered care consistently. They proposed five transforming concepts for adoption by health care organizations seeking such cultural transformative changes:

Surgical Infection Prevention and Surgical Care Improvement Project

Because surgical site infections (SSIs) were recognized as the second most common site of nosocomial infections and a major cause of morbidity, readmissions, excessive costs, and death, the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS) and the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) initiated the National Surgical Care Improvement Project (SCIP) in 2002.4 The goal of surgical infection prevention (SIP) was to reduce the incidence and impact of SSIs in surgical populations, particularly in high-volume procedures. In 2003, the national SIP project convened a meeting of the Surgical Infection Prevention Guideline Writers Workgroup of experts and representatives from several surgical specialty societies to develop evidence-based and consensus guidelines for antimicrobial prophylaxis for abdominal and vaginal hysterectomy, hip or knee arthroplasty, and cardiothoracic, vascular, and colon surgery.

The SIP project has transitioned into the SCIP, and includes additional process performance measures aimed at reducing SSIs. Three additional measures to reduce SSIs have been added to the original SIP measures: (1) glucose control in cardiac surgical patients; (2) appropriate hair removal at the surgical site (using clippers, not razors); and (3) maintenance of normothermia in patients undergoing colorectal operations. In addition to the six performance measures aimed at reducing SSIs, measures aimed at preventing cardiovascular complications and venous thromboembolism after major surgical procedures were proposed (Table 10-1).5 To reduce perioperative ischemic heart complications, patients who have been on β-adrenergic blocking medications prior to operation, should be maintained on beta blockade in the perioperative period and during hospitalization. The final SCIP measures are for the use of appropriate venous thromboembolism prophylaxis in surgical patients at risk for deep venous thrombosis and pulmonary embolism.

| SET MEASURE ID NO. | MEASURE SHORT NAME |

|---|---|

| Infection | |

| SCIP-Inf-1a | Prophylactic antibiotic received within 1 hr prior to surgical incision, overall rate |

| SCIP-Inf-1b | Prophylactic antibiotic received within 1 hr prior to surgical incision, CABG |

| SCIP-Inf-1c | Prophylactic antibiotic received within 1 hr prior to surgical incision, other cardiac surgery |

| SCIP-Inf-1d | Prophylactic antibiotic received within 1 hr prior to surgical incision, hip arthroplasty |

| SCIP-Inf-1e | Prophylactic antibiotic received within 1 hr prior to surgical incision, knee arthroplasty |

| SCIP-Inf-1f | Prophylactic antibiotic received within 1 hr prior to surgical incision, colon surgery |

| SCIP-Inf-1g | Prophylactic antibiotic received within 1 hr prior to surgical incision, hysterectomy |

| SCIP-Inf-1h | Prophylactic antibiotic received within 1 hr prior to surgical incision, vascular surgery |

| SCIP-Inf-2a | Prophylactic antibiotic selection for surgical patients, overall rate |

| SCIP-Inf-2b | Prophylactic antibiotic selection for surgical patients, CABG |

| SCIP-Inf-2c | Prophylactic antibiotic selection for surgical patients, other cardiac surgery |

| SCIP-Inf-2d | Prophylactic antibiotic selection for surgical patients, hip arthroplasty |

| SCIP-Inf-2e | Prophylactic antibiotic selection for surgical patients, knee arthroplasty |

| SCIP-Inf-2f | Prophylactic antibiotic selection for surgical patients, colon surgery |

| SCIP-Inf-2g | Prophylactic antibiotic selection for surgical patients, hysterectomy |

| SCIP-Inf-2h | Prophylactic antibiotic selection for surgical patients, vascular surgery |

| SCIP-Inf-3a | Prophylactic antibiotics discontinued within 24 hr after surgery end time, overall rate |

| SCIP-Inf-3b | Prophylactic antibiotics discontinued within 48 hr after surgery end time, CABG |

| SCIP-Inf-3c | Prophylactic antibiotics discontinued within 48 hr after surgery end time, other cardiac surgery |

| SCIP-Inf-3d | Prophylactic antibiotics discontinued within 24 hr after surgery end time, hip arthroplasty |

| SCIP-Inf-3e | Prophylactic antibiotics discontinued within 24 hr after surgery end time, knee arthroplasty |

| SCIP-Inf-3f | Prophylactic antibiotics discontinued within 24 hr after surgery end time, colon surgery |

| SCIP-Inf-3g | Prophylactic antibiotics discontinued within 24 hr after surgery end time, hysterectomy |

| SCIP-Inf-3h | Prophylactic antibiotics discontinued within 24 hr after surgery end time, vascular surgery |

| SCIP-Inf-4 | Cardiac surgery patients with controlled 6 AM postoperative blood glucose level |

| SCIP-Inf-6 | Surgery patients with appropriate hair removal |

| SCIP-Inf-9 | Urinary catheter removed on postoperative day 1 or 2, with day of surgery being day 0 |

| SCIP-Inf-10 | Surgery patients with perioperative temperature management |

| Cardiac | |

| SCIP-Card-2 | Surgery patients on beta blocker therapy prior to arrival who received a beta blocker during the perioperative period |

| VTE | |

| SCIP-VTE-1 | Surgery patients with recommended VTE prophylaxis ordered |

| SCIP-VTE-2 | Surgery patients who received appropriate VTE prophylaxis within 24 hr prior to surgery to 24 hr after surgery |

VTE, Venous thromboembolism.

From Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services, The Joint Commission: National Hospital Inpatient Quality Measures: Specifications Manual, Version 3.1, June, 2010 (http://www.qualitynet.org/dcs/ContentServer?c=Page&pagename=QnetPublic%2FPage%2FQnetTier4&cid=1228749003528).

Use of Quality Data to Improve Outcomes of Surgical Patients

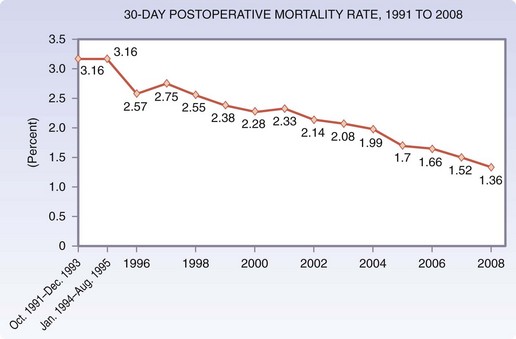

The National Veterans Affairs Surgical Quality Improvement Program was initiated in 1991 to improve surgical outcomes in Veterans Administration (VA) hospitals.6 The NSQIP is a risk-adjusted outcomes database comprised of over 90 data elements gathered by specially trained nurses who review the preoperative, intraoperative, and postoperative periods. This database was validated in the VA system, in which the data are provided back to hospitals and providers and used to inform strategies aimed at reducing morbidity and mortality, with considerable success (Fig. 10-1).7

(From the Congressional Budget Office: Quality initiatives undertaken by the Veterans Health Administration, August 2009 [http://www.cbo.gov/ftpdocs/104xx/doc10453/08-13-VHA.pdf].)

The ACS-NSQIP is a national civilian database launched in 2004 as an outgrowth of the VA NSQIP. The ACS-NSQIP is a prospectively collected, multi-institution clinical registry database of general and vascular surgery patients that provides feedback on risk-adjusted outcomes to member hospitals across the United States for quality improvement purposes; however, the data are also available for population-based research. A recent examination of the ACS-NSQIP data reviewed the overall and major complication rates and risk-adjusted death rates of 84,730 patients who underwent inpatient general or vascular surgical procedures from 2005 through 2007.8 Interestingly, the death rates in these surgical patients ranged from 3.5% in the quintile of very low-mortality hospitals to 6.9% in the quintile of very high-mortality hospitals (double the rate of the low mortality hospitals), whereas the rates of overall and major complications were not significantly different when comparing these two groups of hospitals. The difference in overall risk-adjusted mortality was almost twice as high after a major complication in the very high-mortality hospitals (21.4%) as compared with the very low-mortality hospitals (12.5%). Although processes and systems aimed at the avoidance of complications seem intuitively important, it is not always possible in the performance of complex procedures, particularly in populations at high risk. This report demonstrated that failure to rescue patients after a serious complication was associated with an increased death rate in the high-mortality hospitals as compared with the low-mortality hospitals. The same authors found similar results when analyzing patient outcomes from a Medicare database.9

Effective Teams and Communication

Perioperative team building has parallels in the aviation industry in that teams intermittently come together for relatively short, defined periods of time to accomplish a complex task, requiring the specialized skills of each team member, under potentially stressful conditions in which there is inherent danger. A recent investigation of the impact of implementing a standardized surgical safety checklist (Box 10-1) has demonstrated that complication rates ranged from 6.1% to 21% (total of 11%) of 3733 surgical patients across eight major hospitals in eight cities worldwide and the rate of postoperative death ranged from 0.8% to 3.7% (total of 1.5%) prior to implementation of the checklist.10 After implementation of the surgical checklist with preoperative sign-in, time-out and postprocedural sign-out elements the overall rate of complications decreased to 7% (range, 3.6% to 9.7%) and the rate of death declined to 0.8% (range, 0% to 1.7%).10

Box 10-1 Adapted from Haynes AB, Weiser TG, Berry WR, et al: A surgical safety checklist to reduce morbidity and mortality in a global population. N Engl J Med 360:491–499, 2009.

Elements of the Surgical Safety Checklist

Sign In

Time-Out

Sign Out

Before the patient leaves the operating room, the following are done:

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree