17 Pericardial Disease Chronic inflammatory pericardial diseases, which via fibrous transformation and thickening of the pericardium results in impaired diastolic filling of the heart, are referred to as constrictive pericarditis. In most cases the entire heart is affected. Calcifications may be visible. The etiology is unknown in 40 to 50 % of cases, and the disease is presumably the result of an unrecognized viral pericarditis. Other possible causes are listed in Table 17.1. A prominent hemodynamic finding is impaired diastolic filling of both ventricles. In severe cases the fibrous constriction and the frequently present atrophy of the myocardium can also reduce systolic function. Impaired diastolic filling decreases stroke volume. Due to compensatory tachycardia, cardiac output (CO) is initially still normal at rest but is reduced under stress. In advanced stages, CO is also markedly decreased at rest. When the diagnosis is certain (echocardiography, cardiac CT and cardiac MRI, right heart catheterization), the main indication for cardiac catheterization is to assess coronary status prior to surgery. In case there is diagnostic uncertainty, especially vis-à-vis restrictive myocardial diseases, cardiac catheterization is also indicated. One should be very hesitant to proceed with catheterization in patients with advanced disease and secondary organ damage (cachexia, liver dysfunction), as in most cases the examination has no therapeutic consequences. Table 17.1 Causes of constrictive pericarditis

Constrictive Pericarditis

Pathoanatomical and Pathophysiological Basics

Pathoanatomical and Pathophysiological Basics

Indication

Indication

– Idiopathic (viral pericarditis?) – Tuberculosis – Radiation therapy – Connective tissue disease – Uremic pericarditis – Trauma – Cardiac surgery – Hemorrhagic pericardial effusion |

Procedure

Procedure

Placement of a 5F sheath in the femoral artery and a 6F sheath in the femoral vein

Placement of a 5F sheath in the femoral artery and a 6F sheath in the femoral vein

Catheterization of the left ventricle (pigtail catheter)

Catheterization of the left ventricle (pigtail catheter)

Right heart catheterization with placement of the catheter in PCW position (balloon catheter)

Right heart catheterization with placement of the catheter in PCW position (balloon catheter)

Simultaneous pressure recording PCW/LV

Simultaneous pressure recording PCW/LV

Determination of cardiac output (Fick or thermodilution)

Determination of cardiac output (Fick or thermodilution)

Right heart catheter pullback with pressure recording (PC–PA–RV)

Right heart catheter pullback with pressure recording (PC–PA–RV)

Simultaneous pressure recording LV/RV (volume loading if required)

Simultaneous pressure recording LV/RV (volume loading if required)

Catheter pullback RV–RA, RA-pressure in deep inspiration and expiration

Catheter pullback RV–RA, RA-pressure in deep inspiration and expiration

Simultaneous pressure recording LV/RA

Simultaneous pressure recording LV/RA

Ventriculography, if required right ventriculography

Ventriculography, if required right ventriculography

Left heart catheter pullback (LV–aorta)

Left heart catheter pullback (LV–aorta)

Coronary angiography

Coronary angiography

Findings on Cardiac Catheterization

Findings on Cardiac Catheterization

Hemodynamics/Pressure Waves

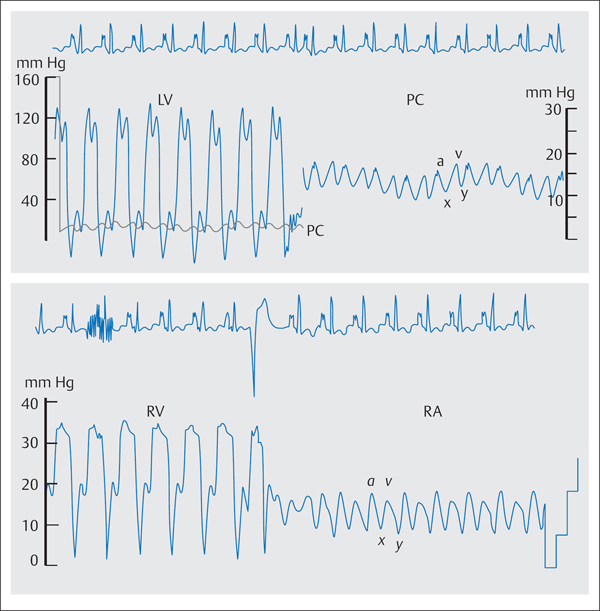

Due to the rapid early diastolic blood flow into the ventricle as well as the impaired filling in mid- and late diastole caused by the constriction, there is a dip–plateau phenomenon in both ventricular pressure waves (Fig. 17.1). The early diastolic pressure is almost always increased to 5 to 10 mm Hg; the subsequent pressure plateau reaches a level of 15 to 35 mm Hg.

As constrictive pericarditis affects the entire heart, the end-diastolic plateau pressure in the left and in the right ventricles is the same, which in turn is also identical to the mean pressure in the right atrium and the mean pulmonary capillary wedge pressure (= left atrial pressure). This differentiates constrictive pericarditis from restrictive myocardial diseases, in which LVEDP usually exceeds the right ventricular end-diastolic pressure by more than 5 mm Hg. Moreover, the right ventricular plateau pressure in constrictive pericarditis is usually more than one-third of right ventricular systolic pressure. The systolic pulmonary artery pressure and the right ventricular pressure are usually between 35 and 45 mm Hg, rarely higher.

Fig. 17.1 Hemodynamics in constrictive pericarditis (typical dip– plateau phenomenon in the ventricular pressure waves, W-configuration of the PCW and RA pressures).

Hemodynamics

Aorta: | 125/80 mm Hg |

LVEDP: | 24 mm Hg PCW |

mean: | 15 mm Hg |

PA: | 25/16 (21) mm Hg |

RV: | 33/3–17 mm Hg |

RA mean: | 13 mm Hg |

CO: | 3.9 L/min |

The atrial pressure wave and the pulmonary capillary wedge pressure wave (Fig. 17.1) demonstrate a typical “M” or “W” configuration: Due to the rapid early diastolic flow into the ventricle, there is after the v-wave a steep decrease to the deep y-descent. As the subsequent atrial contraction cannot pump blood into the already completely filled and stiff ventricle, the pressure wave shows an a-wave with a steep peak and subsequent x- descent; the a-wave and v-wave are usually of the same height. With a less pronounced x-descent the “M”-form develops (e.g., with tachycardia), with a deep x-descent the “W” configuration. However, similar changes in the atrial pressure wave can also be seen in restrictive myocardial diseases.

Kussmaul phenomenon. Constrictive pericarditis prevents the transmission of the negative intrathoracic pressure to the right atrium and ventricle during inspiration. Therefore, the normal inspiratory decrease in right atrial pressure is missing, and the mean pressure during inspiration either remains constant or increases paradoxically. However, this so-called Kussmaul phenomenon is not specific and can also be observed in restrictive myocardial diseases, in right ventricular infarction, in tricuspid valve diseases, and in pulmonary embolism.

Left Ventriculography

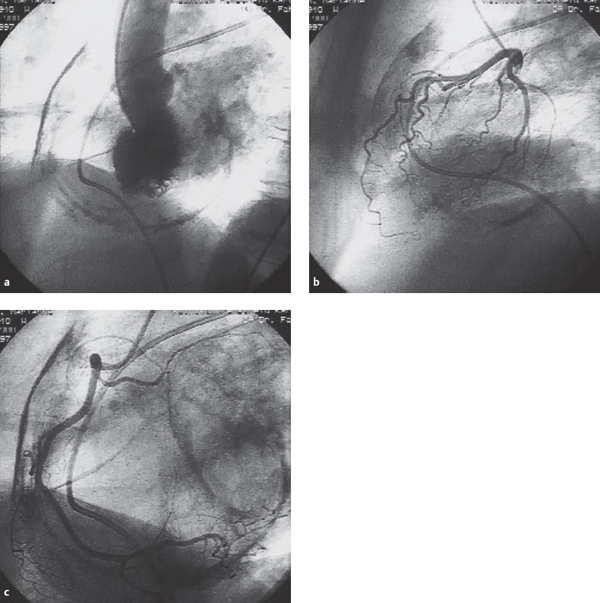

The stroke volume is reduced with a diminished left ventricular cavity and a generally normal or increased ejection fraction. During diastole, the impaired relaxation produces a rapid and complete early diastolic filling of the left ventricle, which in mid- and late diastole appears stiff and immobile. If present, a pericardial calcification can already be recognized during fluoroscopy (Fig. 17.2).

Coronary Angiography

There is usually no special observation on coronary angiography. In some cases a diastolic narrowing of coronary arteries caused by fibrous pericardial thickening has been reported with corresponding symptoms (Table 17.2).

Sources of error. In hypovolemia the typical dip–plateau in the ventricular pressure wave can be absent, even though there is relevant constriction. This is especially true for patients pretreated with diuretics. By rapid but controlled infusion of 1,000 mL normal saline this “occult” constrictive pericarditis can be unmasked.

Fig. 17.2 a–c Constrictive pericarditis (58-year-old woman with marked calcification of the pericardium).

a Left ventriculogram (LAO projection).

b Left coronary artery (lateral projection).

c Right coronary artery (RAO projection). (Courtesy of Dr. Fahrenkrog Klinikum Remscheid, Germany.)

Tachycardia makes recognition of a dip–plateau in the ventricular pressure wave more difficult.

If damping is too low in the pressure-transducer system, the exaggerated spike of the dip can be accentuated with an early diastolic minimum below zero. Due to lack of adequate damping of the atrial contraction, the typical strictly horizontal course of the plateau phase is missing. Conversely, too little damping of the atrial pressure can lead to accentuation of the a– and v-wave as well as of the x-and y-descents, so that a “M” or “W” configuration can also be mimicked.

Interpretation of Findings and Therapy

Interpretation of Findings and Therapy

With respect to patient management, a critical goal of cardiac catheterization is the hemodynamic evaluation of the constriction and the unambiguous differentiation of constrictive pericarditis from a restrictive cardiomyopathy. In most cases the mentioned hemodynamic parameters together with noninvasive findings, such as echocardiography (including Doppler echocardiography and tissue Doppler) and cardiac CT and cardiac MRI, permit a clear differentiation from other myocardial diseases.

Table 17.2 Typical constellation of findings in constrictive pericarditis

Ventricular pressure | Dip–plateau phenomenon in RV and LV, early diastolic pressure increased to 5–10 mm Hg |

RV pressure | RVEDP ⅓ of right ventricular systolic pressure |

Filling pressures | Increased: LVEDP = PCW mean = diastolic PA pressure (PAD) = RVEDP = RA mean |

PA pressure | Systolic PA pressure < 45 mm Hg |

RA pressure | “M” or “W” configuration, Kussmaul phenomenon |

Left ventriculogram | Normal EF, reduced stroke volume, pericardial calcifications in ~40 % of cases |

Coronary angiography | Normal |

Patients with a primary restrictive cardiomyopathy with pericardial involvement and additional functional constriction have findings that are difficult to interpret. Usually the diagnosis can be established by endomyocardial biopsy to evaluate the endocardium and by echocardiography. Only in exceptional cases is an exploratory thoracotomy required.

Therapy. Constrictive pericarditis is a chronic progressive disease, the only definitive therapy of which is complete pericardectomy. The perisurgical mortality is between 7 % and 19 %. Surgery should be done early and is indicated in all symptomatic patients with demonstration of a constrictive pericarditis. Patients with clinical symptoms NYHA III or IV and patients with preexisting chronic kidney disease have a poorer prognosis post surgery. This is also the case for markedly calcified pericardium that cannot be resected, incomplete pericardectomy, and constrictive pericarditis after radiation therapy.

Pericardial Effusion and Pericardial Tamponade

Pathoanatomical and Pathophysiological Basics

Pathoanatomical and Pathophysiological Basics

The pericardium consists of connective tissue and serves to fix the heart in the mediastinum and prevent too much distension of the heart in the setting of volume and pressure overload. Moreover, as it contains both left and right ventricles, it forms one mechanism by which one ventricle influences the filling of the other. Under normal circumstances there is less than 50 mL of serous fluid in the pericardial sac, which keeps the friction low between the smooth inner surfaces of the pericardium.

Table 17.3 Clinical causes of pericardial effusion

– Viral pericarditis – Tuberculosis – Purulent pericarditis – Rheumatic fever – Postcardiotomy syndrome – Pericarditis after myocardial infarction (Dressler syndrome) – Uremic pericarditis – Malignancies/metastases; most frequently lung, breast, and lymphomas – Myocardial rupture after infarction/trauma – Aortic dissection – Iatrogenic – After ventriculography with ventricular perforation – After PCI with coronary perforation – After valvuloplasty – Due to lead perforation after pacemaker implantation – After transseptal puncture – After endomyocardial biopsy – After high-frequency current ablation – Myxedema – Cholesterol pericarditis |

There are many possible causes of a pericardial effusion (Table 17.3). Depending on the etiology, the effusion is either serous (uremia, myxedema), serous-sanguinous (viral pericarditis), purulent (bacterial, trauma) or hemorrhagic (malignancy, myocardial or vascular injury).

Specific Hemodynamics

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree