Penetrating Injury to the Lower Extremity

KIRA N. LONG and TODD E. RASMUSSEN

Presentation

A 24-year-old male is transferred to the resuscitation room from an outlying facility by emergency medical system (EMS) paramedics after having been shot in his left thigh just above the knee. The patient had initially been treated in the operating room of a smaller outlying facility. At the time of the initial operation, the field tourniquet had been removed and the wound explored revealing a transected above-knee popliteal artery and vein. Because of limited resources and experience at the facility, flow across the arterial and venous injuries was restored by placing temporary vascular shunts after the vessels had been controlled and thrombus removed. A left lower extremity fasciotomy was performed at the outlying facility, and the leg was dressed and wrapped for transfer including positioning but not tightening tourniquets above and below the wound in case the shunts became dislodged during transport (Fig. 1). The patient arrives in the resuscitation room with normal vital signs and a well-perfused left foot including a palpable dorsalis pedis pulse.

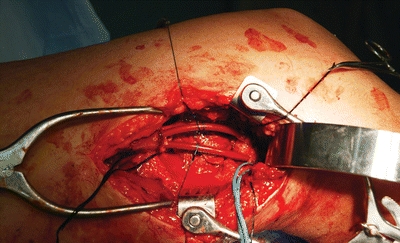

FIGURE 1 Left lower extremity gunshot wound resulting in transected above-knee popliteal artery and vein. The injury was explored at a smaller outlying facility at which time the artery and vein were managed with vascular shunts, a left lower extremity fasciotomy was performed, and the extremity was dressed as shown in the image. The loosely applied Combat Application Tourniquets were positioned at the time of transport in case the shunts became dislodged. Note also the writing on the ace bandage indicating that vascular shunts are in place.

Diagnosis

Signs of Vascular Injury

Penetrating wounds to the lower extremities should always raise suspicion for injury to one of the main arteries or veins in the limb. The diagnosis of vascular injury in this setting is fairly straightforward if the patient has hard signs, which include bleeding from the penetrating wound or wounds, an expanding hematoma around the wound, the presence of an audible bruit, a palpable thrill, or obvious ischemia of the leg. The diagnosis of lower extremity vascular injury is more challenging in the absence of hard signs, and in these cases, a high index of suspicion and additional testing (Doppler or radiographic imaging) is required. Soft signs of vascular injury include the presence of a penetrating fragment or munition near a major vessel, a nonexpanding hematoma, or the report of significant blood loss at the scene of the injury. Neurologic deficit in the extremity is often considered a soft sign of vascular injury as are certain fracture patterns including displaced femur fractures and a displaced fracture of the tibial plateau. Even in the absence of clear ischemia, the examiner’s index of suspicion should be raised if one or more of these soft signs of lower extremity vascular injury are present.

Workup

As one examines the patient with penetrating wounds to the lower extremity, it is useful to consider the differential diagnosis, which , in addition to vascular injury, includes pain from fracture, peripheral nerve injury, or entrapment of a nerve from an adjacent fracture. Pain from the penetrating soft tissue wound itself is often significant and in some cases may be the only significant finding. In the presence of a fracture, the axial vessels of the thigh (femoral or popliteal) and/or leg (tibial vessels) may be misaligned, thus causing reduced or absent pulses or Doppler signals in the foot. In these instances, if the wall of the vessel is uninjured, reduction and alignment of the lower extremity fracture will often result in restoration of perfusion. Similarly, nerve entrapment will also frequently resolve with improvement of distal signs and symptoms after reduction and alignment of the extremity fracture.

Physical examination of patients with penetrating wounds to the lower extremity, gunshot, or other includes assessing the extremity for deformity and evaluation of perfusion to the foot and toes. Depending on the setting, the physical exam can be performed simultaneously with plain radiographs (views of the femur, knee, tibia, and fibula) to diagnose and assess the severity of any fracture. Palpation for the femoral pulse at the inguinal ligament, the popliteal pulse behind the knee, and the posterior tibial and dorsalis pedis pulses in the foot should be performed and capillary refill estimated in the toes.

Continuous wave Doppler is an extension of the physical exam in patients with penetrating wounds to the lower extremity and Doppler signals should be assessed at the same locations at which pulses were palpated. Strong, biphasic signals audible at these locations argue against a significant artery injury, while weak, monophasic or absent arterial signals indicate a flow-limiting arterial defect. To more objectively assess perfusion of the leg and foot, one should measure the injured extremity index (IEI). Also referred to as the ankle-brachial index (ABI), the IEI is a ratio of the occlusion pressure of the distal arterial Doppler signal in the injured compared to the noninjured lower extremity. To accomplish this, a manual blood pressure cuff is placed over the leg of the injured extremity and inflated while the Doppler signal is assessed at the posterior tibial and then the dorsalis pedis artery. The cuff pressure at which the arterial signal occludes or is no longer audible at each of the arterial locations should be recorded and these steps repeated on an uninjured upper extremity (i.e., the brachial artery). The IEI or ABI is calculated by dividing the highest occlusion pressure on the injured lower extremity by the occlusion pressure of the upper extremity with a normal index being 0.9 or greater. The IEI or ABI provides a more objective and repeatable measure by which to assess for lower extremity arterial injury and is especially useful in scenarios where perfusion distal to a femur or tibial fracture may not be obvious (Table 1).

Additional Imaging versus Operation

Patients with hard signs of lower extremity arterial injury (i.e., external hemorrhage, profound or obvious ischemia, arteriovenous fistula, and expanding hematoma) such as those in the case scenario provided at the beginning of the chapter typically do not need additional imaging or workup prior to being taken to the operating room. One exception to this is the case in which the patient has additional injuries that require further imaging. For example, if a patient has hard signs of lower extremity hemorrhage requiring tourniquet application, little additional imaging of the leg may be necessary before exploring the wound in the operating room. However, if this same patient has other penetrating or blunt injuries, he or she may very well require imaging (i.e., head, chest, and abdomen) prior to commencing treatment of the penetrating lower extremity wounds.

Patients who have femur and/or a tibial fracture and less clear signs of vascular injury (i.e., modestly reduce ABI, audible but abnormal sounding Doppler signals, equivocal capillary refill) pose a more challenging diagnostic scenario. In these cases, additional imaging with arteriography, contrast tomography (CT), or duplex ultrasonography may be useful in making the decision as to whether or not to operate on the artery. However, unlike blunt or closed trauma, patients with gunshot or fragmentation injury to the lower extremity require operative debridement and washout of the soft tissue wound(s) regardless of concern for vascular injury.

Because of the relatively superficial nature of the arteries of the lower extremity, duplex ultrasound is often the imaging modality of choice as it is quick, inexpensive, noninvasive, and able to be repeated. However, traditional catheter-based arteriography or CT angiography may also be used to discern the presence of flow-limiting defects or injuries in the femoral, popliteal, or tibial vessels with CT providing particularly detailed information when there is concern for fracture.

It is important to note that in all cases of penetrating lower extremity with fracture, the initial step in management, often even before additional imaging, is fracture reduction and stabilization of the extremity. This can often be performed outside of the operating room following hemorrhage control, initiation of resuscitation, and pain control measures. In nearly all cases of significant fracture with dislocation or misalignment, this management step should be pursued regardless of initial signs of vascular injury. Depending on the severity of and the time since the injury, reducing and stabilizing a femur or tibial fracture may favorably change perfusion to the leg and foot and improve the vascular exam. In most cases of mild to moderate fracture, the decision as to whether or not to operate on or further image the lower extremity vessels is made after the fracture is reduced and the vascular exam is repeated. If signs of vascular injury persist after fracture reduction and stabilization, then additional imaging with one of the previously noted modalities is indicated. In cases of extreme open femur or tibial fracture (i.e., the mangled extremity), fracture reduction and stabilization and exploration of the vessels should occur simultaneously in the operating room.

Treatment Decision

If physical signs of ischemia are present or persist after fracture reduction, efforts to restore normal perfusion to the leg and foot should be undertaken in most cases. In the lower extremity, the decision to operate on an arterial injury is highly dependent on the anatomic location of the injury. Proximal injuries to the common femoral artery require repair in nearly all cases as the degree of collateral circulation around this large inflow vessel is not sufficient to maintain viability to the leg and foot. Although injuries distal to the profunda femoris artery are somewhat better tolerated, the superficial femoral and popliteal arteries should also be repaired in the majority of cases. This is especially true in the setting of penetrating injury in which collaterals from the proximal common, profunda, and superficial femoral arteries will have been interrupted by the soft tissue wound(s).

In contrast to the femoral and popliteal arteries, a selective approach to tibial artery repair is recommended (i.e., repair some but not all). Because of the redundant nature of the tibial vessels (anterior tibial, posterior tibial, and peroneal), it is common that one or even two of these arteries may be injured without rendering the leg or foot critically ischemic. The selective approach to tibial artery repair is made while balancing the severity of extremity ischemia with the patient’s overall injury and physiologic condition. The complexity of a tibial vessel reconstruction in the setting of penetrating trauma will require seasoned vascular surgery experience and several hours of operating. In some cases in which the degree of ischemia to the leg and foot is in question or incomplete, the tibial artery may be ligated or restored with a temporary vascular shunt while the patient is resuscitated and an experienced vascular team assembled.

The practice of damage control surgery or abbreviated operating refers to limiting the physiologic stress or compromise from the initial operation, which should focus only on controlling hemorrhage and contamination and restoring critical ischemia. Within the bounds of damage control surgery, it is also recognized that extremity vascular ligation with or without immediate amputation may be the necessary operation. This maneuver typically applies to the significantly mangled extremity in which repair would be futile or judged to put the patient’s physiologic condition or life at risk.

Surgical Approach

Lower extremity vascular injury should be approached with an open surgical incision in nearly all cases. While isolated reports of catheter-based (i.e., endovascular) treatment of this injury pattern exist, the superficial and accessible nature of the lower extremity vasculature makes it most amenable to open repair. To expose and operate on any lower extremity vascular injury from a penetrating mechanism, the patient should be placed supine on the operating table and the lower abdomen and groins shaved and included in the surgical scrub. Including these proximal aspects in the surgical field allows one access to the external iliac and common femoral arteries should inflow control be needed or access for arteriography. The surgical scrub and prep should also include both lower extremities from the groin to and including the feet and toes. Access to the distal aspect of the extremity allows one to fully position the limb and assess perfusion following exploration and management of the injury—repair, ligation, or shunting. To facilitate concurrent management of any extremity fracture(s) and/or performance of angiography, it is useful to have the patient positioned on a radiolucent table and to have mobile fluoroscopy available in the room.

The common, profunda, and proximal superficial femoral arteries should be approached through a longitudinal incision at and just distal to the inguinal ligament. The incision should be positioned proximal enough to allow exposure and control of the femoral artery, which can include extending the exposure proximal onto the lower abdomen and retroperitoneum. In the inguinal space and just distal to this, the femoral artery rests between the femoral vein and nerve.

The superficial femoral artery extends distally in the thigh exiting through the adductor magnus (i.e., adductor or Hunter’s canal) above the knee where it transitions to the popliteal artery (Fig. 2). The femoral vessels in the thigh should be approached through a medial incision reflecting the sartorius muscle either up (superior or lateral) or down (inferior) depending on whether the incision is proximal or distal, respectively. Throughout its course in the thigh, the superficial femoral and then popliteal artery is adjacent and often adherent to its sister femoral vein. There are three notable anatomic features of the adductor canal: (1) the superficial femoral artery becomes the above-knee popliteal artery, (2) the saphenous nerve becomes a superficial structure, and (3) the supreme geniculate artery or arteries arise from the axial femoral artery.

FIGURE 2 At the time of exploration of the injury in the case, vascular shunts were found in the proximal popliteal artery and vein. The shunts had been secured with silk suture ties, and both were patent with Doppler flow several hours after the injury. Note also the operative approach that includes a Wietlaner retractor proximally, a Henly popliteal retractor, and a short handheld Wylie renal vein retractor to expose the behind the knee segment.