13

CHAPTER

![]()

Pediatric Disorders

This chapter reviews selected conditions occurring in infants and young children that are likely to be encountered by surgical pathologists. It does not include entities that are mostly found at autopsy.

TOPICS

Pulmonary Sequestration

Pulmonary Sequestration

Intralobar Sequestration

Intralobar Sequestration

Extralobar Sequestration

Extralobar Sequestration

Congenital Cystic Adenomatoid Malformation (CCAM)/Congenital Pulmonary Airway Malformation (CPAM)

Congenital Cystic Adenomatoid Malformation (CCAM)/Congenital Pulmonary Airway Malformation (CPAM)

Bronchogenic Cyst

Bronchogenic Cyst

Congenital Pulmonary Overinflation (Emphysema)

Congenital Pulmonary Overinflation (Emphysema)

Pulmonary Interstitial Emphysema

Pulmonary Interstitial Emphysema

Congenital Pulmonary Lymphangiectasis

Congenital Pulmonary Lymphangiectasis

Diffuse Lymphangiomatosis

Diffuse Lymphangiomatosis

Interstitial Lung Disease in Children

Interstitial Lung Disease in Children

Bronchopulmonary Dysplasia (BPD) (Chronic Neonatal Lung Disease)

Bronchopulmonary Dysplasia (BPD) (Chronic Neonatal Lung Disease)

Chronic Pneumonitis of Infancy (CPI)

Chronic Pneumonitis of Infancy (CPI)

Pulmonary Interstitial Glycogenosis (PIG)

Pulmonary Interstitial Glycogenosis (PIG)

Interstitial Pneumonias

Interstitial Pneumonias

Neuroendocrine Cell Hyperplasia of Infancy (NEHI)/Persistent Tachypnea of Infancy

Neuroendocrine Cell Hyperplasia of Infancy (NEHI)/Persistent Tachypnea of Infancy

PULMONARY SEQUESTRATION

Pulmonary sequestration is defined as a portion of lung that does not communicate with the tracheobronchial tree and receives its blood supply from the systemic circulation. Sequestrations can occur within an otherwise normal lobe (intralobar) or they can be entirely separate from the normal lung with their own pleural investment (extralobar). Their main features are contrasted in Table 13.1.

INTRALOBAR SEQUESTRATION

There is a debate whether intralobar sequestration is a true congenital anomaly or whether it develops after birth secondary to recurrent infection. According to the latter theory, recurrent infection leads to destruction of a portion of the bronchial tree and pulmonary vascular connection, thus causing enlargement of systemic arterial branches that are normally present in the inferior pulmonary ligament. Some evidence exists in support of both mechanisms, and although the latter is favored, it is possible that different pathogeneses exist for different cases.

Gross examination of the resected specimen along with the information from the surgeon regarding the blood supply to the affected area is important in diagnosing intralobar sequestration. The pathologist should attempt to find the systemic feeding artery during the initial gross examination. If the feeding artery cannot be identified grossly, however, the surgeon should confirm its presence.

Gross Features

Thick-walled aberrant artery usually in medial basal area of the lobe

Thick-walled aberrant artery usually in medial basal area of the lobe

Nonspecific solid to cystic parenchymal destruction

Nonspecific solid to cystic parenchymal destruction

Usually the aberrant artery is found near the medial basal area of the lobe, often associated with adhesions, and it stands out as a thick-walled blood vessel that normally would not occur in that location (Figures 13.1 and 13.2). Elsewhere the involved parenchyma may appear solid to cystic with varied yellow-white areas depending on the amount of associated inflammation and fibrosis.

TABLE 13.1 Contrasting Features of Intralobar and Extralobar Sequestration

Feature | Intralobar | Extralobar |

Age at diagnosis | 50% >20 years | 60% <1 year |

Sex distribution | M:F = 1:1 | M:F = 3–4:1 |

Relation to lung | Within | Separate (outside of visceral pleura) |

Side affected | Left, 60% | Left, 90% |

Venous drainage | Pulmonary | Systemic or portal |

Associated anomalies | Rare | Present in 50% (diaphragmatic defects, pectus excavatum, cardiovascular malformations) |

Pathogenesis | Acquired or congenital | Congenital |

M:F, male:female.

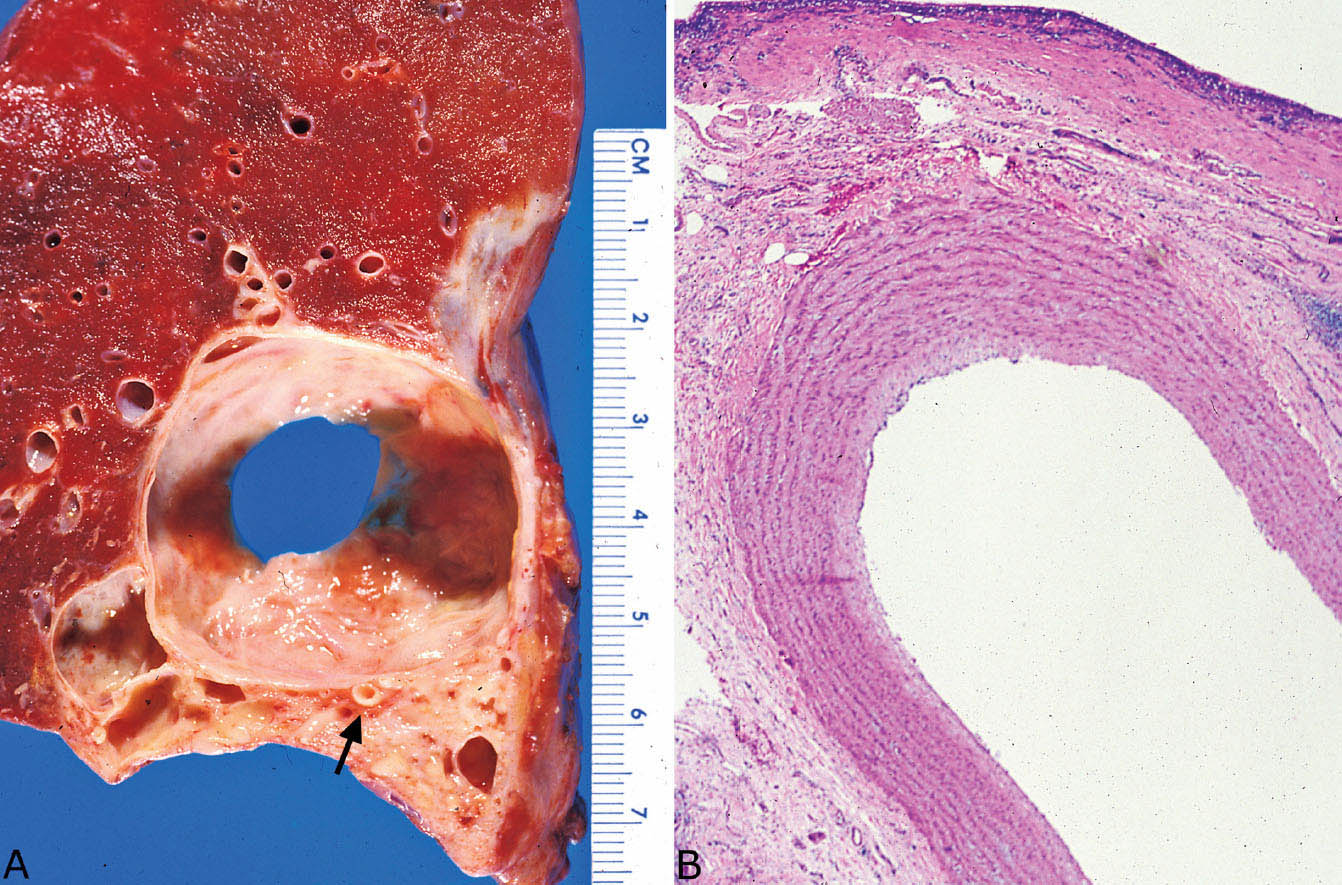

FIGURE 13.1 Intralobar sequestration. This left lower lobe is partially replaced by areas of solid yellow-white consolidation representing acute inflammation and fibrosis as well as cystic areas resulting from healed infections. A thick-walled systemic (feeding) artery is seen near the base (arrow).

Histologic Features

Features of systemic artery in the feeding artery

Features of systemic artery in the feeding artery

Changes of pulmonary hypertension in pulmonary arteries

Changes of pulmonary hypertension in pulmonary arteries

Parenchymal destruction by nonspecific inflammatory changes and fibrosis

Parenchymal destruction by nonspecific inflammatory changes and fibrosis

Sections from the feeding artery show a thick-walled systemic artery containing multiple parallel elastic layers between the smooth muscle of the media (Figure 13.2B). In cases in which the feeding artery is not grossly identifiable, a systemic arterial supply can be inferred from the presence of hypertensive vascular changes (see Chapter 10) elsewhere, including marked intimal and medial hyperplasia in muscular pulmonary arteries (Figure 13.3). Although similar vascular changes may occur secondary to parenchymal scarring, they are more severe and more extensive than can be explained by fibrosis alone.

The parenchyma of sequestrations shows changes related to recurrent infection, and they vary depending on patient age. The findings are nonspecific, however, and include acute and chronic inflammation, foamy macrophages (postobstructive pneumonia), scarring and cysts in varying proportions. Rarely, skeletal muscle fibers have been described in sequestrations (so-called rhabdomyomatous dysplasia).

Clinical Features

About one half of intralobar sequestration cases occur in children, with the remaining in persons older than 20 years. Most patients have a history of recurrent pneumonia with fever, cough, and chest pain, although some are asymptomatic. Radiographically, localized infiltrates, inhomogeneous masses, and cysts are described.

FIGURE 13.2 Intralobar sequestration. (A) This example is predominantly cystic grossly with focal surrounding fibrosis. A large systemic (feeding) artery is present near the base (arrow). (B) Section of the artery noted grossly in A confirms a systemic elastic artery. The cyst (top) is lined by fibrosis and chronic inflammation.

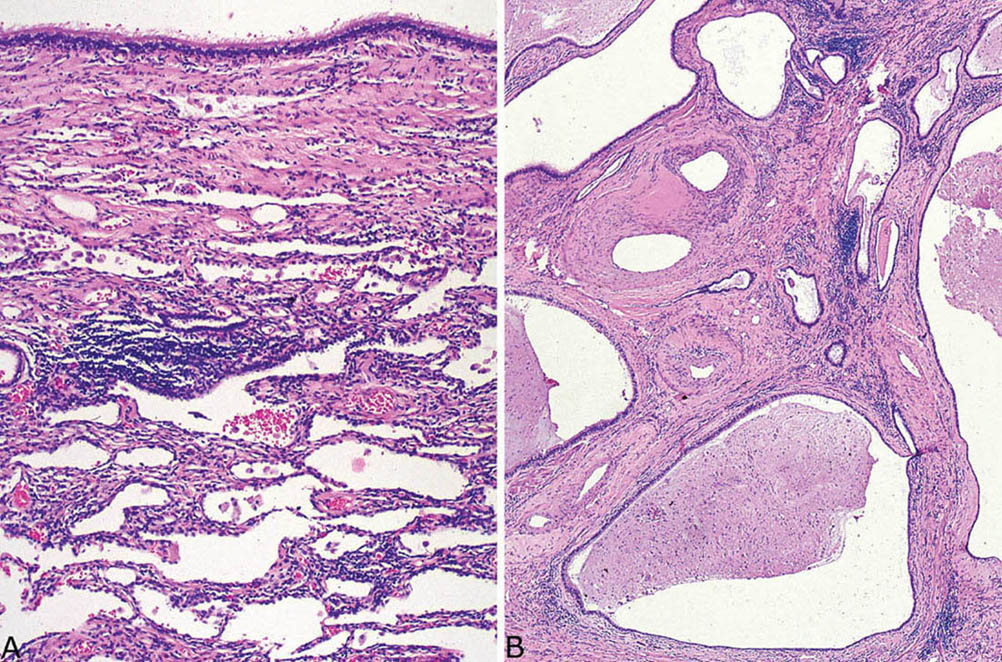

FIGURE 13.3 Microscopic findings in intralobar sequestration. Same case as in Figure 13.2. (A) Nonspecific fibrosis and chronic inflammation surround the cyst, which in this area has a respiratory tract epithelial lining (top). (B) Elsewhere in the grossly fibrotic area, the parenchyma is destroyed by fibrosis and chronic inflammation. Note the central arteries with marked intimal and medial hypertrophy indicative of pulmonary hypertension.

Helpful Tip—Intralobar Sequestration

Be sure to look carefully on the gross specimen for a feeding systemic artery; if one is not identified grossly, confirm with the surgeon that there was a systemic blood supply before diagnosing intralobar sequestration.

Be sure to look carefully on the gross specimen for a feeding systemic artery; if one is not identified grossly, confirm with the surgeon that there was a systemic blood supply before diagnosing intralobar sequestration.

EXTRALOBAR SEQUESTRATION

In contrast to intralobar sequestrations, extralobar sequestrations are separate from the lung, and they have their own pleural covering. Most are found in the thorax, especially the left lower, but they can be encountered within or below the diaphragm, including the retroperitoneum. In contrast to intralobar sequestrations, they clearly represent congenital malformations, and are thought to develop from an accessory lung bud arising from the primitive foregut.

Gross Features

Spongy, sometimes cystic, tan mass separate from lung with its own pleural surface

Spongy, sometimes cystic, tan mass separate from lung with its own pleural surface

Occasional pedicle connecting to the lung

Occasional pedicle connecting to the lung

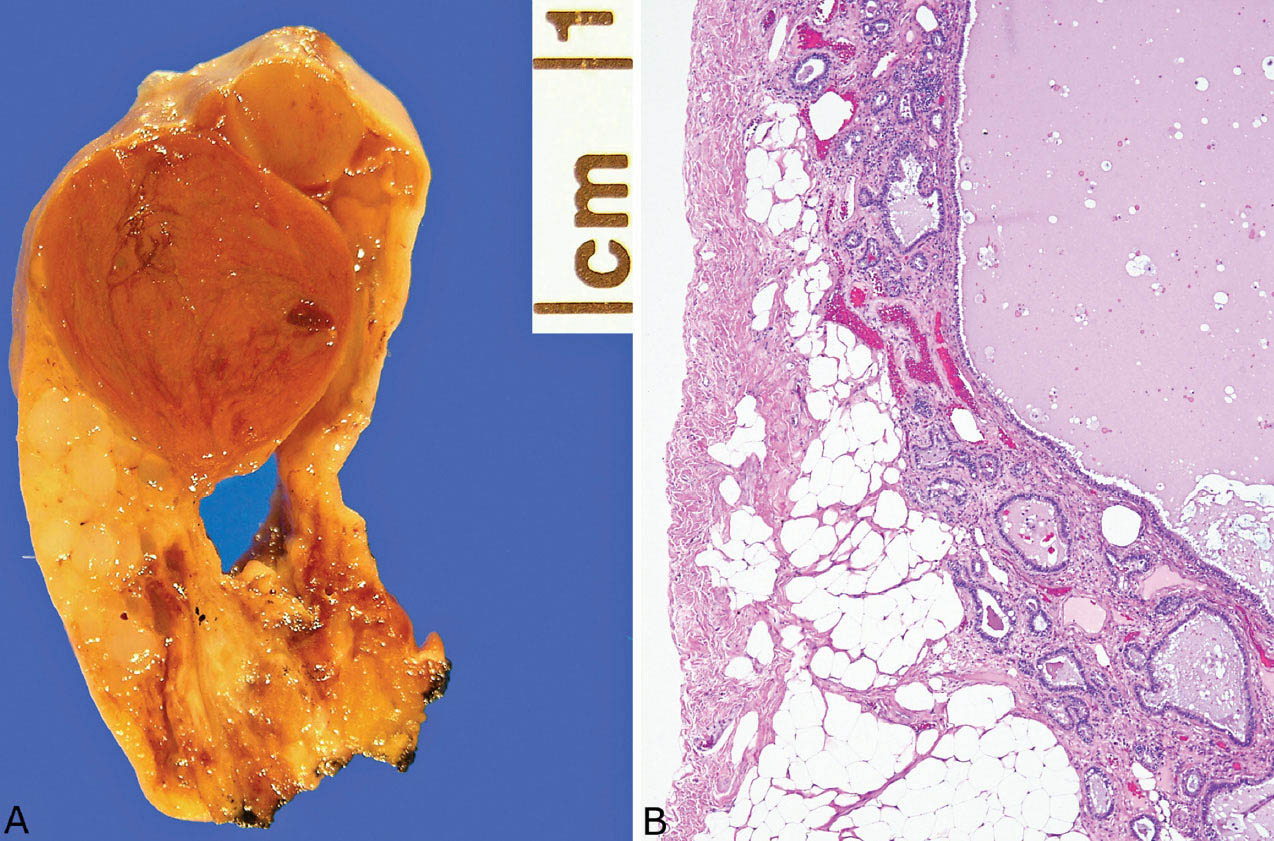

Grossly, extralobar sequestrations appear as spongy, sometimes cystic, tan masses covered by their own pleural surface and surrounded by variable adipose or connective tissue depending on their location (Figure 13.4). In the thorax, they may be connected to the pleura of the lung by a thin stalk.

Histologic Features

Normal lung or lung containing irregular proliferation of bronchiole-like structures resembling congenital adenomatoid malformation

Normal lung or lung containing irregular proliferation of bronchiole-like structures resembling congenital adenomatoid malformation

Varying amounts of inflammation and fibrosis

Varying amounts of inflammation and fibrosis

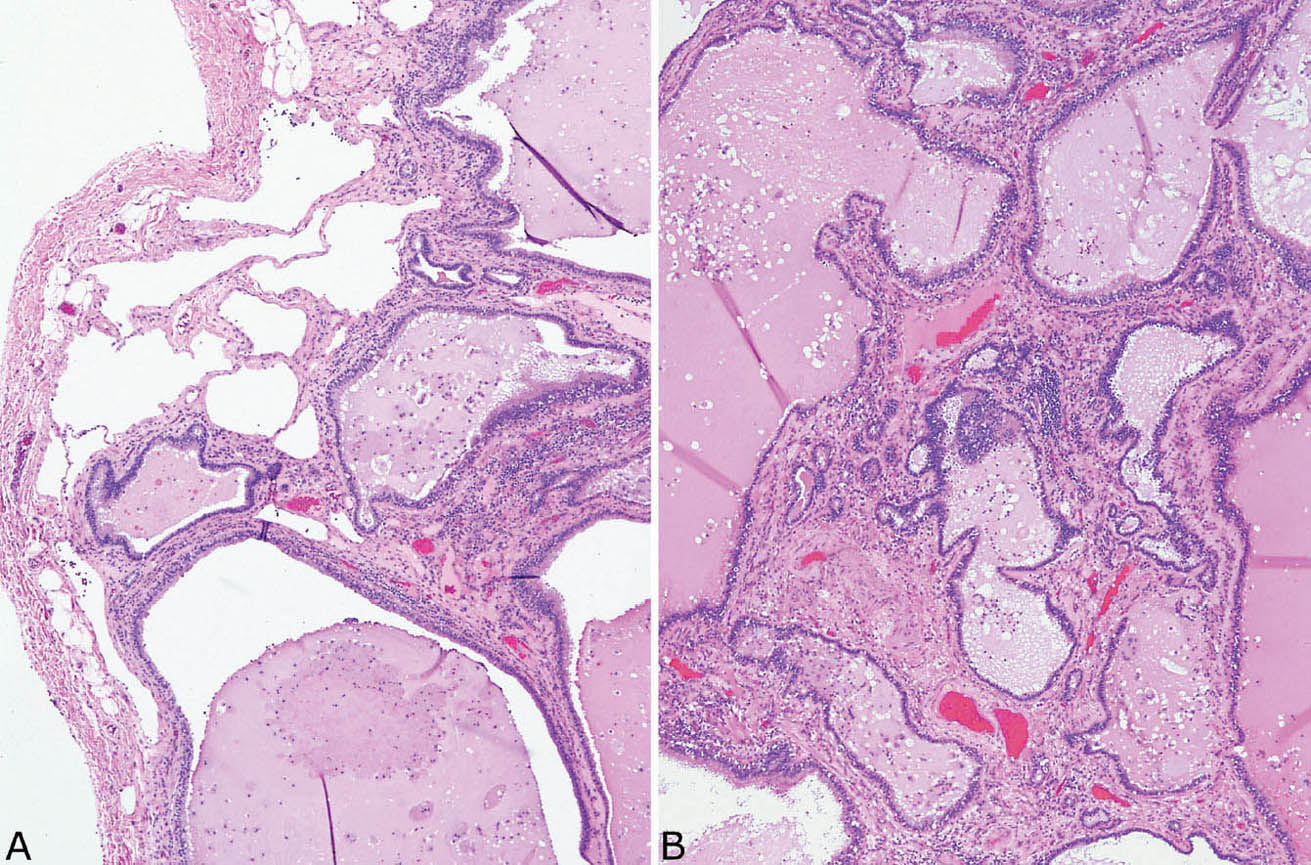

As with intralobar sequestration, the histologic features of extralobar sequestration vary somewhat depending on patient age. In young children in whom infections have not developed the appearance is that of either normal lung or lung containing irregular, haphazard bronchiole-like structures resembling congenital cystic adenomatoid malformation (CCAM; Figure 13.5, see subsequent section, “Congenital Cystic Adenomatoid Malformation/Congenital Pulmonary Airway Malformation”). Variable distortion of the parenchyma by inflammation with fibrosis and scarring related to recurrent infection may be present in older children and adults (Figure 13.6).

FIGURE 13.4 Extralobar sequestration. (A) This specimen was present in the pleural cavity and attached by a stalk (bottom) to the pleura. Grossly, it appeared cystic and solid. (B) Microscopically, the cystic area is lined by respiratory tract epithelium, and there is surrounding fibrotic parenchyma containing varying sized bronchiole-like structures. The lesion was an incidental finding in a 68-year-old man, and it was removed because of the radiographic suspicion of a neoplasm.

FIGURE 13.5 Extralobar sequestration. In this case, bronchiole-like structures unaccompanied by pulmonary arteries are irregularly distributed within alveolated parenchyma. The appearance is reminiscent of congenital adenomatoid malformation (compare with Figures 13.8 and 13.9). This lesion was present near the adrenal gland of a young child and was removed because it was thought to represent a retroperitoneal tumor.

Differential Diagnosis

When encountered in unexpected locations outside of the thorax or in unusual clinical settings, such as an older child or adult, teratomas and bronchial cysts might be considered in the differential diagnosis. Teratomas differ in that they tend to be multilocular and contain ectodermal and mesodermal components in addition to endodermal derivatives. Furthermore, the presence of well-formed alveoli along with the pleural covering militates against teratoma. Bronchogenic cysts (see subsequent section, “Bronchogenic Cysts”) contain bronchial glands and cartilage at least focally in their walls, and alveolated parenchyma is not a feature. When the bronchiole-like structures are prominent in an adult, adenocarcinoma may enter the differential diagnosis, but the presence of ciliated epithelium indicates the benign nature of the lesion.

Clinical Features

Most extralobar sequestrations are found in children younger than 1 year, with boys predominating, but the lesion can also be found in older children and adults. Most cases in infants are incidental findings during surgery for other abnormalities, especially repair of diaphragmatic hernias. In older children or adults, they may be found on radiographs taken for other reasons, and they are excised because of the resemblance to a neoplasm. A few patients present with signs and symptoms of infection.

Extralobar sequestration is often associated with other congenital anomalies, especially diaphragmatic defects, whereas funnel chest (pectus excavatum) and cardiovascular abnormalities such as patent ductus arteriosus and ventricular septal defect are found less often.

Helpful Tips—Extralobar Sequestration

Extralobar sequestration can be found within extrathoracic sites as well as in the thorax.

Extralobar sequestration can be found within extrathoracic sites as well as in the thorax.

Extralobar sequestration may be encountered in adults in whom it is usually excised because of the clinical suspicion of neoplasm. The clue to diagnosis is the presence of both bronchiole-like structures and alveoli.

Extralobar sequestration may be encountered in adults in whom it is usually excised because of the clinical suspicion of neoplasm. The clue to diagnosis is the presence of both bronchiole-like structures and alveoli.

CONGENITAL CYSTIC ADENOMATOID MALFORMATION (CCAM)/CONGENITAL PULMONARY AIRWAY MALFORMATION (CPAM)

Congenital cystic adenomatoid malformation (CCAM) is a rare developmental anomaly that combines features of immaturity and malformation of the small airways and distal lung parenchyma. Some prefer the term congenital pulmonary airway malformation (CPAM) based on the supposition that the lesion is related to developmental abnormalities emanating from the tracheobronchial tree. Many cases are diagnosed prenatally.

Classification

CCAM has been divided on the basis of gross and histologic findings into five types, which are listed in Table 13.2. Although this classification scheme emphasizes the spectrum of changes that may be encountered in CCAM, it is not entirely practical, because, at least in our experience, it is not always possible to pigeonhole cases into a single subtype. Furthermore, it may not be applicable to cases occurring in immature lungs, which are encountered when the lesion is removed by prenatal intrauterine surgery. Types 0 and 3 are incompatible with life, and are not further discussed.

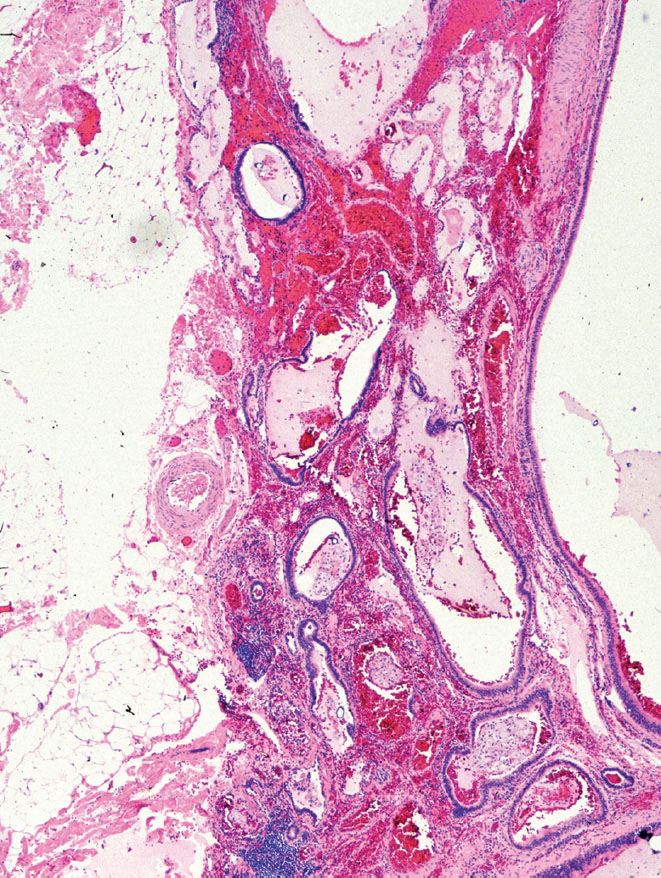

FIGURE 13.6 Extralobar sequestration. Same case as in Figure 13.4. (A) In this area, remnants of relatively normal alveolated parenchyma (top left) are present beneath the pleura adjacent to fibrosis with scarring containing bronchiole-like structures. (B) Bronchiole-like structures within background fibrosis and chronic inflammation predominate in this area, and the appearance resembles honeycomb change.

TABLE 13.2 Congenital Adenomatoid Malformation

Type | Gross Appearance | Microscopic Appearance |

0 | Solid | Bronchial-like structures, abundant cartilage |

1 | Large multilocular cysts 3 to 10 cm | Cysts with ciliated respiratory tract epithelium, smaller irregular bronchiolar-like structures, frequent mucigenic cells, occasional cartilage |

2 | Small uniform cysts <2 cm | Small cysts with ciliated respiratory tract epithelium and irregular bronchiolar-like structures, rare striated muscle bundles |

3 | Solid, bulky lesion, cysts <0.2 cm | Irregular curved channels and small spaces lined by low cuboidal epithelium |

4 | Large cysts, up to 7 cm, in peripheral lung | Thin-walled cysts lined by Type 1 pneumocytes and low columnar epithelium, cellular stroma |

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree