9

CHAPTER

![]()

Pneumoconiosis

Pneumoconioses are diseases caused by inhalation of environmental dusts, and most are diagnosed by a combination of clinical history and imaging studies. This chapter includes only selected examples that are likely to be encountered on lung biopsy or surgical specimens either as incidental findings or because they are unsuspected clinically.

TOPICS

Asbestosis

Asbestosis

Silicosis

Silicosis

Nodular Silicosis

Nodular Silicosis

Acute Silicosis

Acute Silicosis

Mixed Dust Pneumoconiosis

Mixed Dust Pneumoconiosis

Hard Metal Pneumoconiosis

Hard Metal Pneumoconiosis

Miscellaneous Pneumoconiosis

Miscellaneous Pneumoconiosis

Berylliosis

Berylliosis

Talcosis

Talcosis

Coal Workers’ Pneumoconiosis

Coal Workers’ Pneumoconiosis

Aluminosis

Aluminosis

Siderosis

Siderosis

Flock Workers’ Lung

Flock Workers’ Lung

ASBESTOSIS

Asbestosis is defined pathologically by the combination of diffuse interstitial fibrosis and asbestos bodies. Most cases are diagnosed clinically based on radiographic findings and a strong history of asbestos exposure. Although biopsy may be taken in a few cases to confirm the diagnosis, more often asbestosis is encountered by pathologists at autopsy or in lobectomy specimens removed for other reasons. It should be remembered that the presence of isolated asbestos bodies in the absence of fibrosis, while indicating exposure, is not diagnostic of asbestosis.

Histologic Features

Diffuse interstitial fibrosis

Diffuse interstitial fibrosis

Asbestos bodies in airspaces or interstitium

Asbestos bodies in airspaces or interstitium

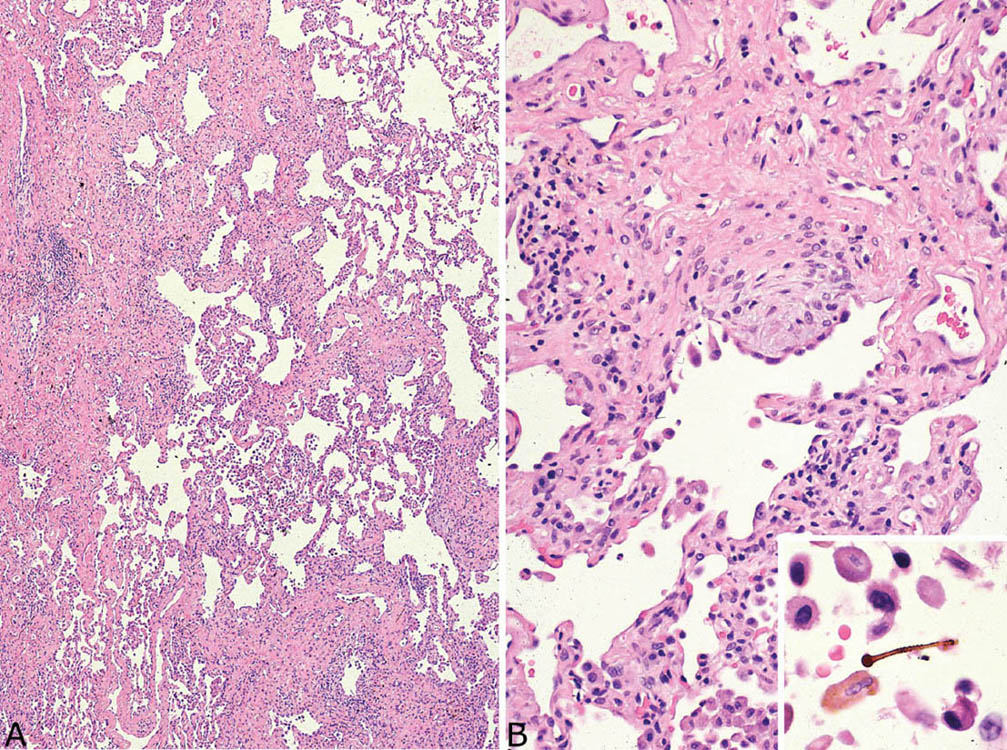

Asbestosis causes chronic interstitial fibrosis that varies in appearance. Some cases resemble usual interstitial pneumonia (UIP; see Chapter 3) with the characteristic heterogeneous low-magnification appearance with areas of fibrosis and scarring alternating with islands of normal lung. Fibroblast foci are present but usually not numerous (Figure 9.1). Honeycomb change may occur as well but is usually not as prominent as in idiopathic UIP. Other cases may show a more uniform-appearing fibrosis that resembles the fibrotic variant of nonspecific interstitial pneumonia (NSIP; see Chapter 3; Figure 9.2). It is characterized by diffuse thickening of alveolar septa by collagen deposition with minimal inflammation and without significant honeycomb change or scarring. Peribronchiolar accentuation of the interstitial fibrosis may be seen, and peribronchiolar metaplasia (see Chapter 3), characterized by growth of bronchiolar-type epithelium along adjacent fibrotic alveolar septa, is common (Figure 9.2B). Peribronchiolar metaplasia generally reflects chronic bronchiolar injury, but is not specific for asbestosis. Visceral pleural fibrosis often accompanies the parenchymal changes, and its presence in cases of interstitial fibrosis should raise suspicion of asbestosis. It is not a specific finding, however, as it can occur in association with other entities, especially collagen vascular diseases.

FIGURE 9.1 Asbestosis resembling UIP. (A) A low-magnification view shows patchwork lung involvement by alternating zones of fibrous scarring and normal lung typical of UIP. (B) At higher magnification, a fibroblast focus is seen within a collagenized scar. The inset shows a typical asbestos body with golden-brown iron deposits around a clear core present within an alveolar space. UIP, usual interstitial pneumonia.

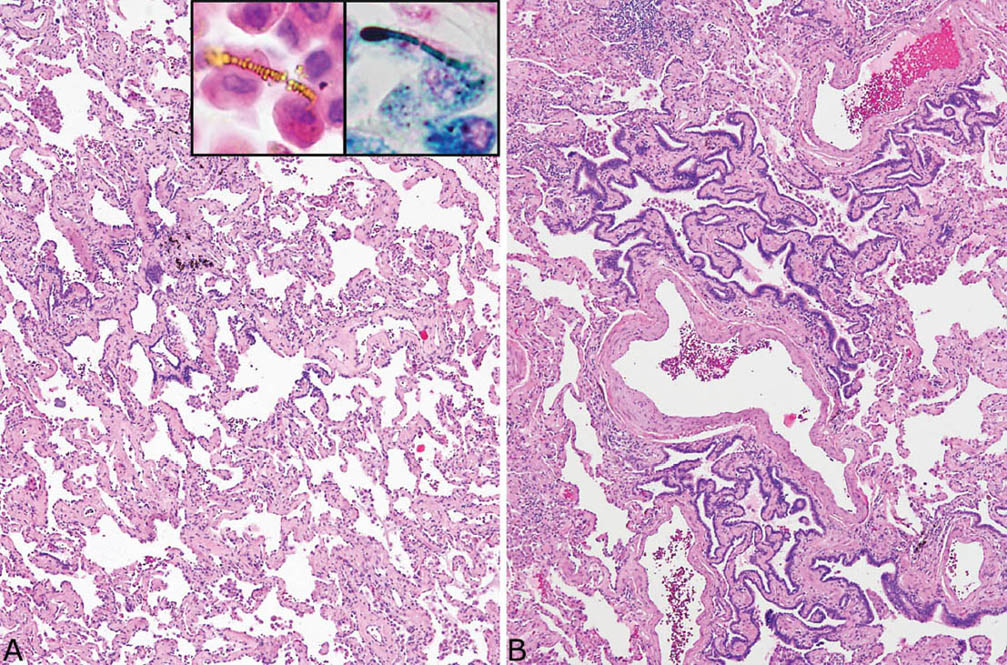

FIGURE 9.2 Asbestosis resembling fibrotic NSIP. (A) A low-magnification view shows diffuse, uniform thickening of alveolar septa by collagen deposition with minimal inflammation that resembles fibrotic NSIP. Scattered asbestos bodies were present within alveolar spaces, visible in both H and E (inset, top, left) and Prussian blue iron stains (inset, top right). (B) Another area from the same case shows peribronchiolar metaplasia (see Chapter 3) characterized by the growth of bronchiolar epithelium along fibrotic peribronchiolar alveolar septa. H and E, hematoxylin and eosin; NSIP, nonspecific interstitial pneumonia.

Fibrosis confined to bronchiole walls and not involving adjacent alveolar septa may also be encountered in asbestos-exposed persons. It is referred to as “asbestos airways disease,” but is not considered diagnostic of asbestosis in the absence of alveolar septal fibrosis.

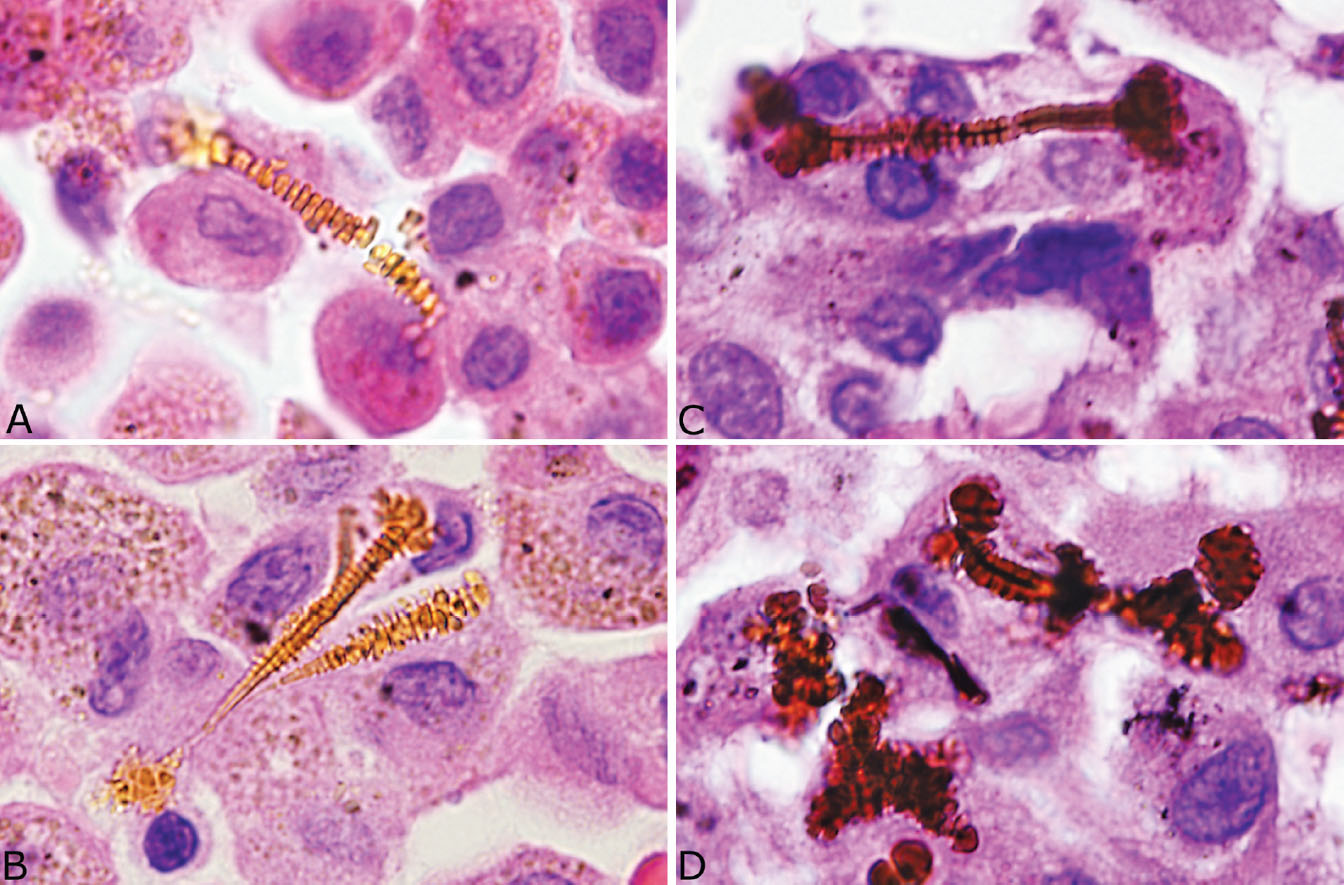

Identification of asbestos bodies is essential to confirm the diagnosis of asbestosis in cases of chronic interstitial fibrosis. Although asbestos bodies may be numerous and easy to find in end-stage cases at autopsy, they are often scant in biopsy or surgical specimens. Examination of the slides at high magnification is usually needed to find them as they are easily overlooked at low magnification. Use of the Prussian blue iron stain in which they appear dark blue against the pink background can facilitate their identification (Figure 9.2, right inset). In hematoxylin and eosin (H and E) stains, they are elongated structures ranging from 10 to more than 100 μm in length and 1 to 6 μm in diameter (Figures 9.3A and 9.3B). Most are straight but some are curved, and occasional branching forms occur. The diagnostic feature is a golden-yellow coating often with a beaded appearance and thick knob-like projections on both ends that surround a distinct clear core. The clear core is the asbestos fiber, which is visible in H and E stains only after becoming coated with iron, thus forming the asbestos body. Asbestos bodies are a type of ferruginous body, which is a generic name for all iron-coated particles including asbestos bodies. Other ferruginous bodies related to nonasbestos dusts contain brown or black rather than clear cores (Figures 9.3C and 9.3D). A ferruginous body can be identified as an asbestos body with confidence in routine light microscopy when a clear core is present.

There is debate about the number of asbestos bodies needed to diagnose asbestosis. In our opinion, the presence of a single asbestos body in a biopsy showing chronic interstitial fibrosis should be considered highly suspicious, and the patient carefully questioned regarding potential exposure in the past. It is well known, however, that asbestos bodies can be incidental findings in lungs from persons in the general population who had no specific exposure. Therefore, in the absence of an exposure history, a single asbestos body in a biopsy specimen should be considered an incidental finding.

It is important to remember that asbestosis is a chronic illness with insidious onset over years. Patients with asbestos exposure, however, may develop acute or subacute respiratory illnesses unrelated to asbestos exposure, and temptation to attribute these illnesses to asbestosis should be resisted. It is likely, therefore, that the occasional case of organizing pneumonia reported as a manifestation of asbestosis is coincidental.

FIGURE 9.3 Contrasting features of asbestos bodies and ferruginous bodies. (A, B) Classic asbestos bodies characterized by beaded golden-yellow iron deposits along a clear central core. (C, D) Ferruginous bodies, in contrast, although having a beaded iron coating, contain a black rather than a clear central core that excludes asbestos bodies.

Clinical Features

Asbestosis results from heavy asbestos exposure over a prolonged period of time, and a 15- to 20-year latent period is usually present before symptoms are noted. Patients present with the insidious onset of cough and dyspnea similar to the presentation of other chronic interstitial fibrosing diseases. Diffuse reticular-linear opacities with lower lobe accentuation are seen, and pleural plaques are common. The diagnosis is usually made clinically and depends on a strong exposure history combined with clinical and radiographic findings indicative of interstitial fibrosis.

Other Reactions to Asbestos

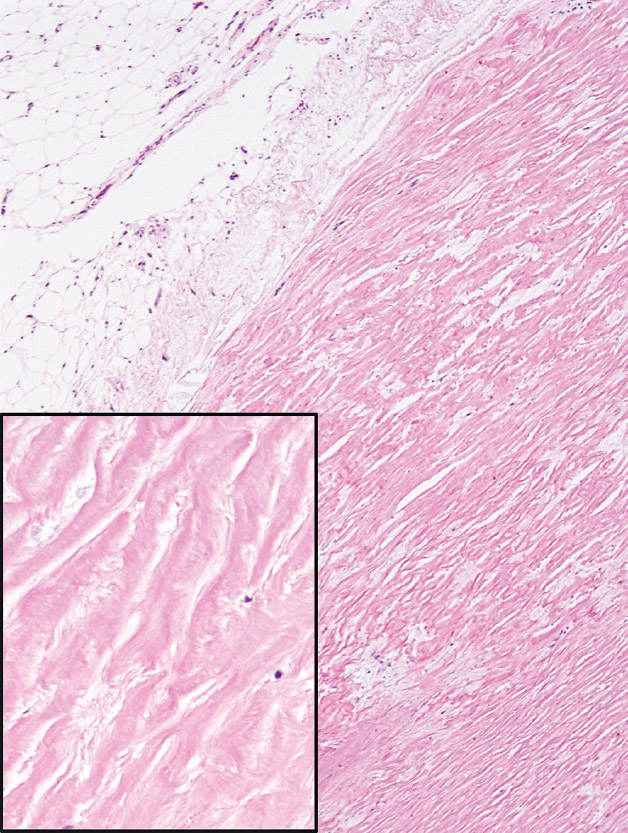

A number of non-neoplastic reactions in addition to interstitial fibrosis may result from asbestos exposure, but none are indicative, by themselves, of asbestosis. Pleural plaques are common markers of asbestos exposure. They may be found as isolated findings in the absence of underlying lung abnormality, or they may occur in patients with interstitial fibrosis and thus asbestosis. They involve predominantly the parietal pleura and are composed of dense, hyalinized collagen bundles that cause pleural thickening (Figure 9.4). The collagen bundles are arranged in a distinct lamellar pattern with a few, if any, intervening cells. Areas of calcification are common. Diffuse pleural fibrosis and chronic pleuritis are less common complications of asbestos exposure involving the pleura. Round atelectasis is another uncommon manifestation. It is related to invagination of thickened, fibrotic pleura into the underlying lung where it may appear as a mass radio-graphically. It is discussed in more detail in Chapter 12 and illustrated in Figures 12.19 and 12.20.

FIGURE 9.4 Pleural plaque. A low magnification illustrates the closely packed relatively acellular collagen bundles comprising the plaque. Note the adipose tissue (top left) indicating parietal pleural. The inset is a higher magnification showing the characteristic acellular collagen bundles arranged in parallel.

Helpful Tips—Asbestosis

Asbestos bodies indicate exposure, but by themselves are not indicative of asbestosis; they should be considered incidental findings unless accompanied by diffuse interstitial fibrosis.

Asbestos bodies indicate exposure, but by themselves are not indicative of asbestosis; they should be considered incidental findings unless accompanied by diffuse interstitial fibrosis.

Acute or subacute lung abnormalities (eg, organizing pneumonia and diffuse alveolar damage) should not be considered asbestos related, even when accompanied by asbestos bodies.

Acute or subacute lung abnormalities (eg, organizing pneumonia and diffuse alveolar damage) should not be considered asbestos related, even when accompanied by asbestos bodies.

When only a rare asbestos body is found in diffuse interstitial fibrosis, the diagnosis of asbestosis must be confirmed by a history of appropriate exposure.

When only a rare asbestos body is found in diffuse interstitial fibrosis, the diagnosis of asbestosis must be confirmed by a history of appropriate exposure.

SILICOSIS

Silicosis is caused by the inhalation of crystalline silica particles. There are two main forms of the disease, nodular silicosis and acute silicosis. Nodular silicosis is more common and occurs following a long latent period. Acute silicosis occurs after only a few years and is related to heavy exposure to silica over a short period of time.

NODULAR SILICOSIS

Histologic Features

Well-demarcated nodules composed of hyalinized, concentrically arranged collagen bundles surrounded by a rim of pigment-containing histiocytes.

Well-demarcated nodules composed of hyalinized, concentrically arranged collagen bundles surrounded by a rim of pigment-containing histiocytes.

Birefringent, 1- to 2-μm particles usually visible under polarized light.

Birefringent, 1- to 2-μm particles usually visible under polarized light.

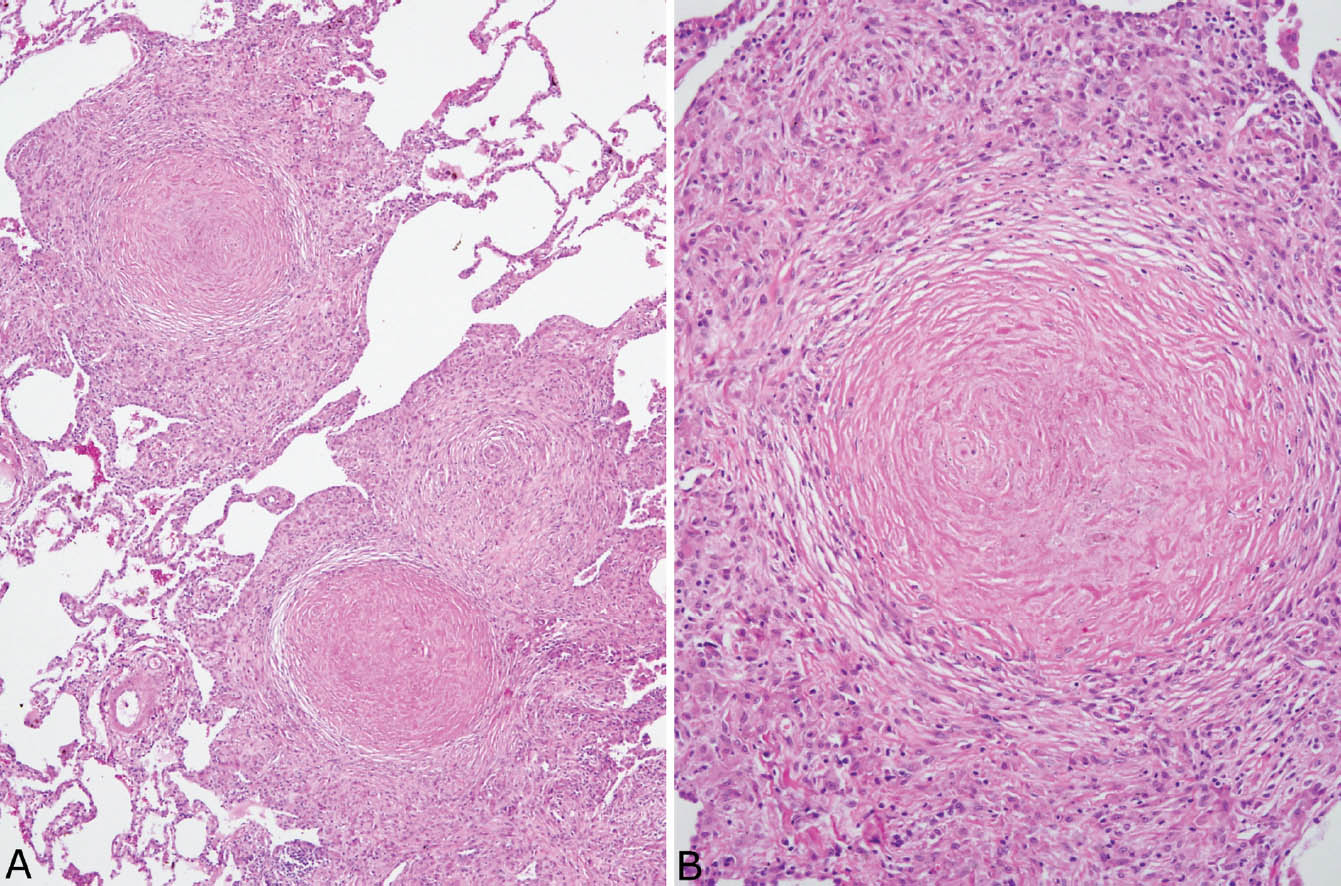

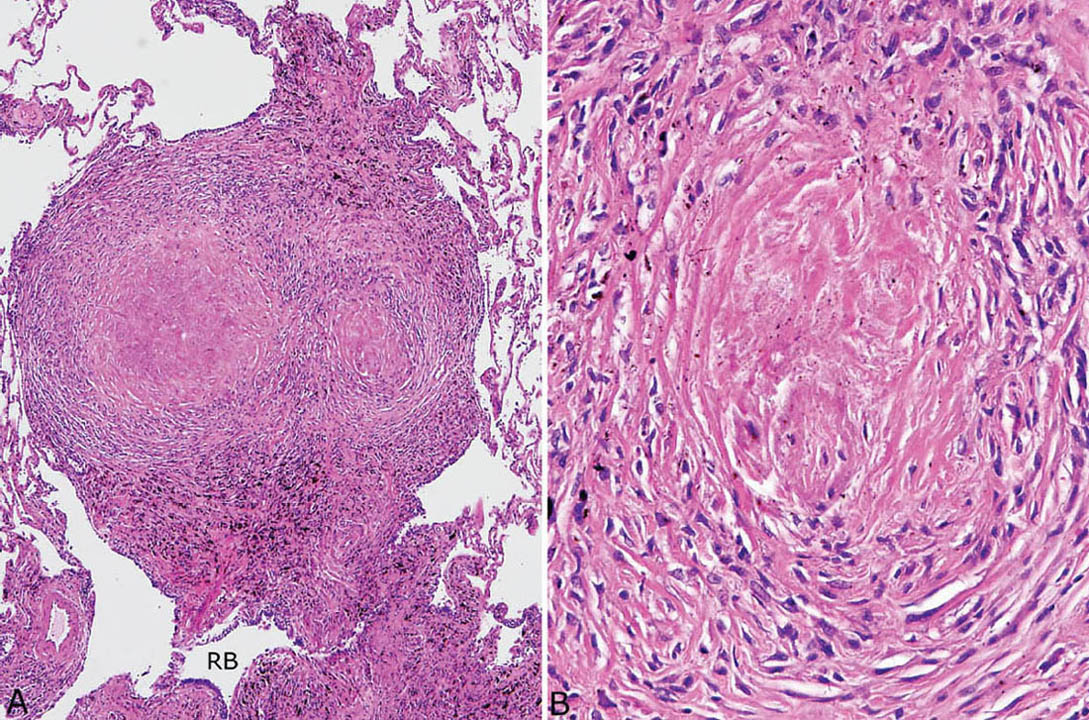

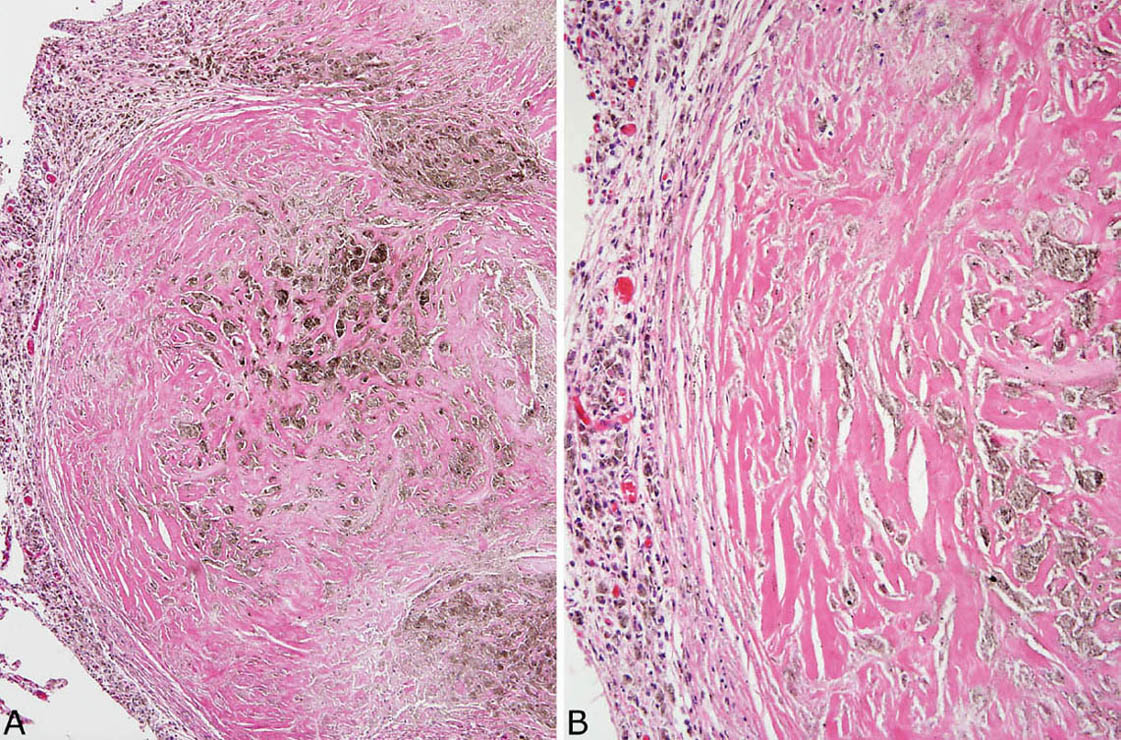

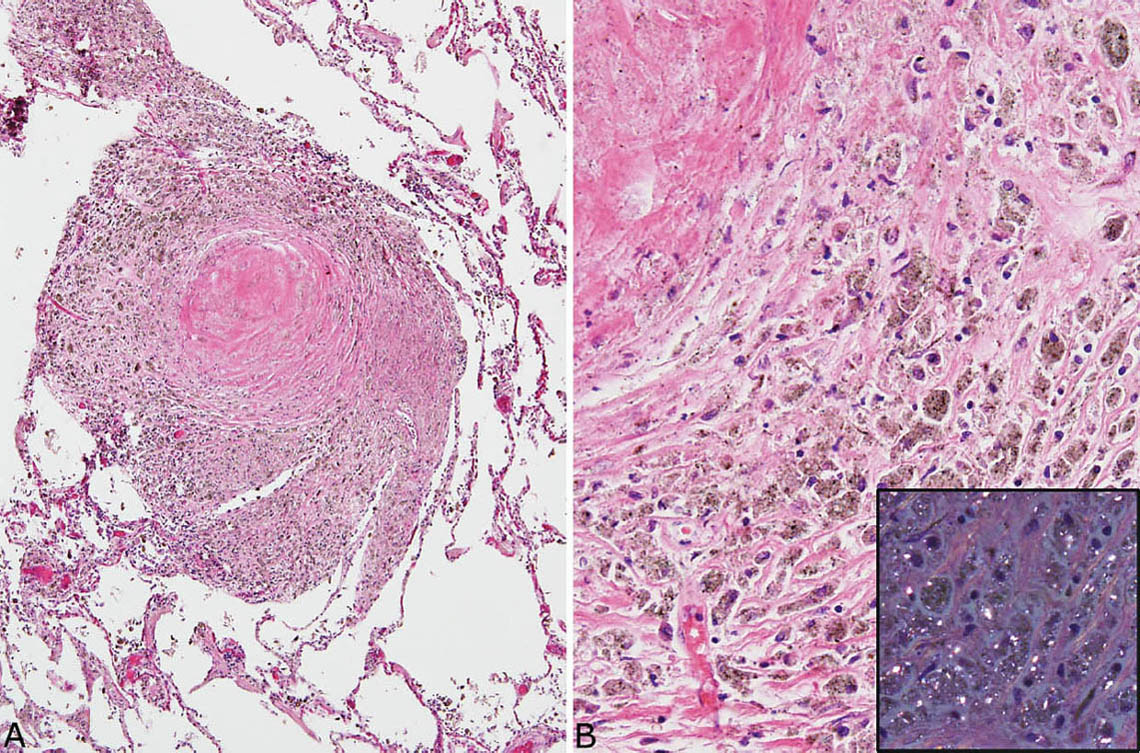

Nodular silicosis is characterized by small nodular lesions composed of variable proportions of collagen and histiocytes that are present in the interstitium usually in the vicinity of respiratory bronchioles (Figures 9.5 and 9.6). They are well demarcated from adjacent parenchyma and have rounded to occasionally stellate borders. Typically, there is a central core of hyalinized collagen composed of thick collagen bundles arranged in a concentric lamellar pattern. This central fibrous core is surrounded by a peripheral rim of histiocytes that may be quite thick in early lesions, but thinner in older lesions in which collagen deposition may predominate (Figure 9.7). The amount of pigment deposition within the collagenous core and the surrounding histiocytes varies from minimal to striking. Under polarized light, small, oval-shaped 1- to 2-μm birefringent crystals are visible in most cases (Figure 9.8).

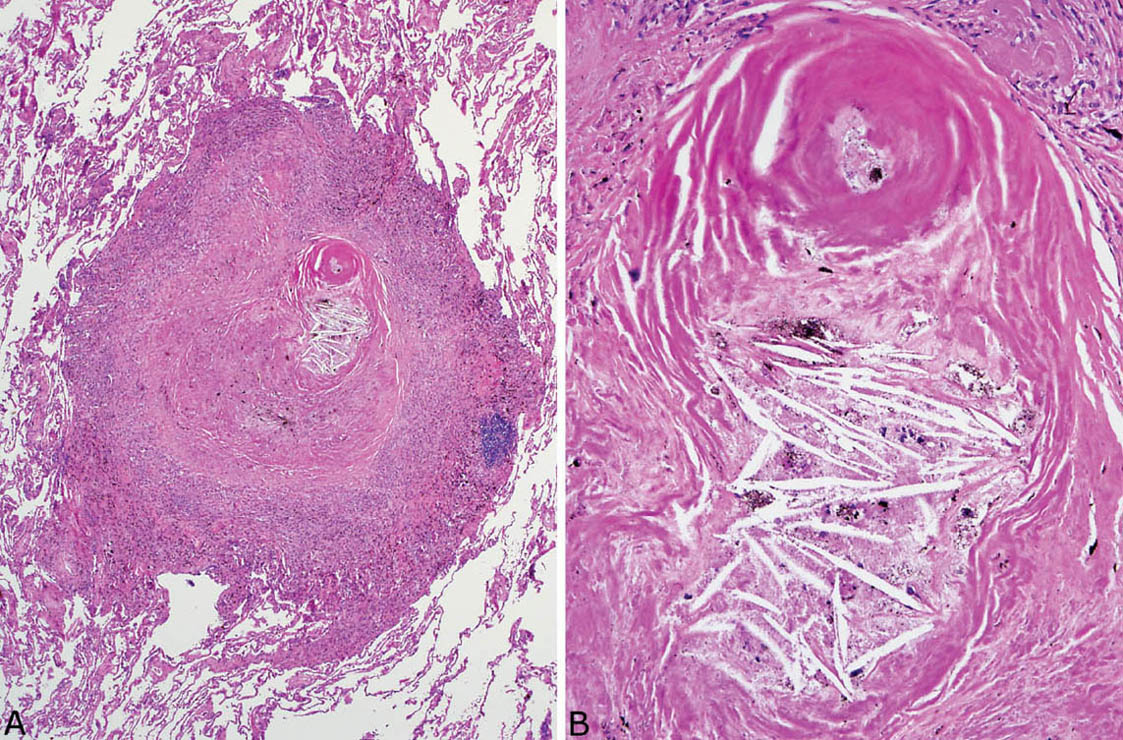

FIGURE 9.5 Nodular silicosis. (A) Low magnification showing well-demarcated nodular infiltrates having rounded to stellate shapes composed of hyalinized centers surrounded by a thick rim of histiocytes. (B) A higher magnification shows the concentrically arranged collagen bundles in the center along with scant brown black pigment deposition.

FIGURE 9.6 Nodular silicosis. (A) At low magnification, this well-demarcated nodule adjacent to a respiratory bronchiole (RB) has rounded borders, and pigment deposition is striking. (B) Higher magnification shows the collagenous core and surrounding lamellar collagen bundles intermingled with histiocytes.

Necrosis, likely ischemic in etiology, is sometimes present in the collagenous center of silicotic nodules, but well-formed granulomatous inflammation with surrounding epithelioid histiocytes is not a feature (Figure 9.9). As infections, especially atypical mycobacterial infections, may complicate silicotic nodules, it is important to examine special stains for organisms whenever necrosis is present, even in the absence of granuloma formation.

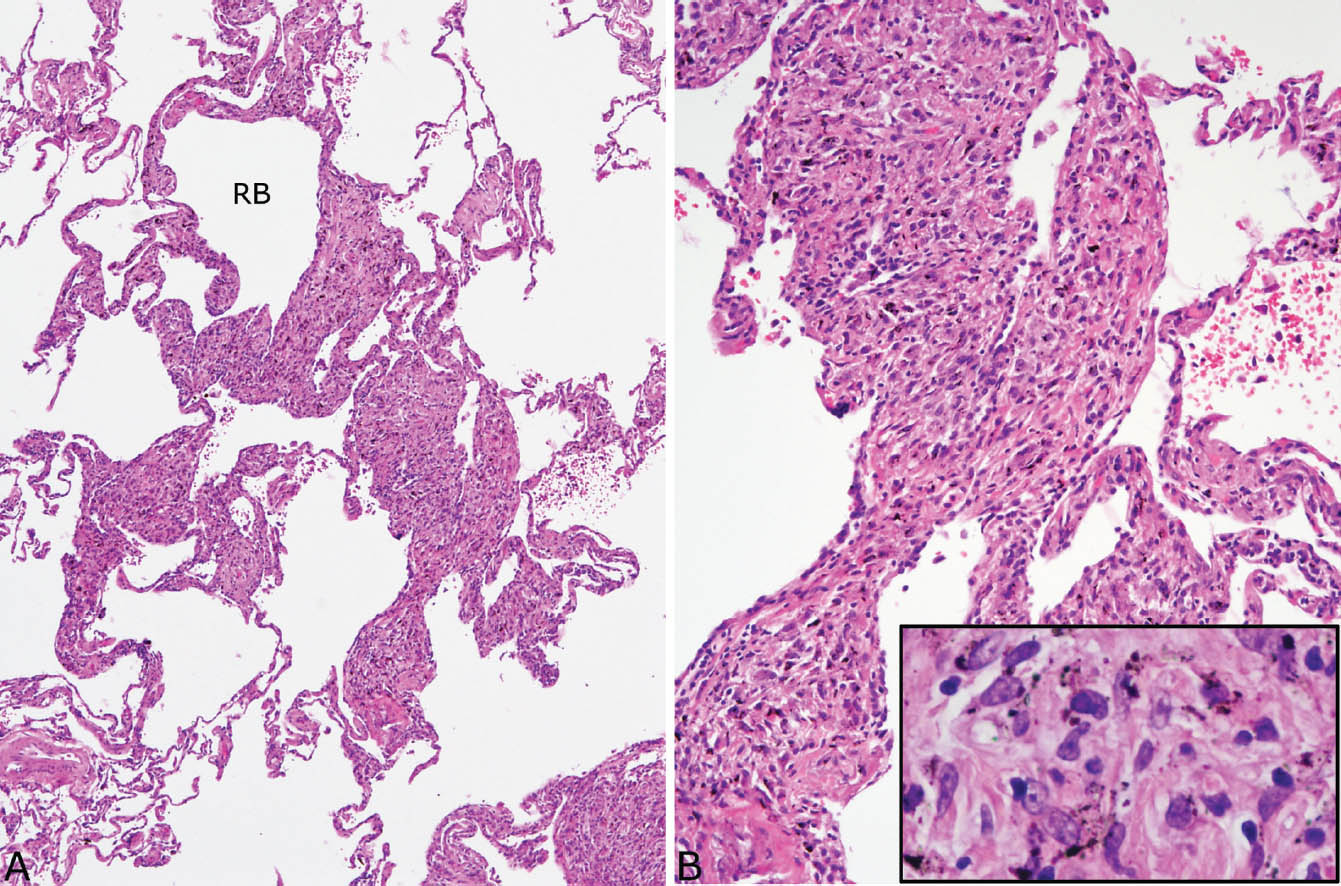

Dust macules are often present in the interstitium not involved by silicotic nodules (Figure 9.10). These lesions are a common reaction to many inhaled dusts, and they are not specific for silicosis. They are characterized by expansion of peribronchiolar and perivascular interstitium by collections of pigment-containing histiocytes. They are sharply demarcated from adjacent interstitium and are usually irregularly shaped. Increased numbers of pigment-containing macrophages are also often present in the lumens of respiratory bronchioles, alveolar ducts, and surrounding airspaces and are indicative of respiratory bronchiolitis (Chapter 11). The latter lesion most commonly results from cigarette smoking, but may also result from exposure to other dusts.

In a few patients, large fibrotic lesions (by definition greater than 1.0 cm) are produced that extensively destroy the parenchyma. They are composed of confluent silicotic nodules with extensive surrounding fibrosis, and they are indicative of progressive massive fibrosis (PMF). PMF is a well-documented complication of silicosis as well as other pneumoconioses, such as mixed dust fibrosis and coal workers’ pneumoconiosis (CWP) see subsequent section, “Coal Workers’ Pneumoconiosis,” for example. Silicosis is recognized in the etiology of PMF by the presence of typical silicotic nodules within the fibrosis.

Clinical Features

Most cases of nodular silicosis occur after 20 or more years of low-level exposure, whereas, less commonly, heavier exposures for 5 to 10 years may produce an accelerated form of the disease. Symptoms are variable. Many patients are asymptomatic with their disease first noted on routine chest radiographs. Some present with mild chest complaints, including cough and dyspnea, while a few patients, mainly those in whom PMF has developed, have symptoms of respiratory insufficiency. Some patients in whom a history of silica exposure is not elicited undergo biopsy because the radiographic appearance of the nodules is suggestive of a malignant neoplasm.

FIGURE 9.7 Nodular silicosis. (A) In this example, the silicotic nodule is almost entirely collagenized with only a thin surrounding rim of histiocytes (left). Note the striking pigment deposition. (B) A higher magnification view highlights the dense, lamellar collagen bundles and pigment.

FIGURE 9.8 Nodular silicosis. (A) This heavily pigmented nodule consists mainly of a thick histiocyte rim with only a small collagenous core. (B) A higher magnification view shows the prominent pigmented histiocytes that, under polarized light (inset), contain numerous small birefringent crystals.

FIGURE 9.9 Necrosis in nodular silicosis. (A) At low magnification, central necrosis with cholesterol clefts is present in this silicotic nodule. The characteristic rim of histiocytes is present, but there is no organized granulomatous inflammation. (B) A higher magnification view shows the necrotic zone with cholesterol clefts and pigment deposition.

FIGURE 9.10 Dust macules in silicosis. (A) Irregular expansion of the interstitium around a respiratory bronchiole (RB) and adjacent alveolar duct is visible at low magnification. (B) At higher magnification, abundant histiocytes are seen in the widened alveolar septa, and many contain black-brown pigment (inset).

The typical radiographic findings include multiple, small, subcentimeter nodular densities predominantly in the upper lobes. In a few patients, enlarged hilar and mediastinal lymph nodes with peripheral “eggshell” calcification may accompany the parenchymal lesions. In PMF, the coalescence of the small nodules leads to larger (more than 1.0 cm in diameter) opacities sometimes mimicking neoplasms, and the associated fibrosis may obliterate portions of the upper lobes.

ACUTE SILICOSIS

Acute silicosis results from heavy exposure to silica dusts occurring over a relatively short time span (1–3 years). The disease is classically described in sandblasters and differs both clinically and pathologically from nodular silicosis. Unlike nodular silicosis, most patients are symptomatic with the acute onset of cough and dyspnea. Bilateral, diffuse ground glass opacities are seen on chest radiographs.

The histologic findings are nearly identical with pulmonary alveolar proteinosis (PAP; Chapter 4; see Figures 4.34–4.36) and characterized by the filling of airspaces by a granular eosinophilic exudate. The main difference from idiopathic PAP is that interstitial inflammation with fibrosis and pigment deposition commonly accompanies the airspace exudate. Scattered dust macules may be present as well, but silicotic nodules are usually not seen.