INDICATIONS/CONTRAINDICATIONS

Pectus excavatum is the most common chest wall deformity in infants, children, and adolescents. Its incidence is estimated between 1 in 400 live births and 7.9 per 1,000 births. There is a male to female ratio of 3:1. The etiology of pectus excavatum is unknown. There is a positive family history of chest wall abnormalities in 37% of cases.

The sternal deformity in pectus excavatum may be either symmetrical or asymmetrical. In the asymmetric deformity, the more severe depression is typically on the right side. In up to 90% of cases, the deformity can be seen within the first year of life.

Children with pectus excavatum may present with symptoms of shortness of breath, dyspnea on exertion, and fatigue. Symptomatic improvement is frequently noted after repair. However, consistent improvement in pulmonary function tests does not follow the repair. Due to the “restrictive” nature of the defect, symptomatic improvement may be due to the relief of anterior compression of the heart, especially on the right ventricle, as well as the release of pulmonary compression. In addition to the physiologic components of the deformity, affected children also can have adverse psychological consequences.

Indications for surgery include both assessments of physiologic and psychological implications of the condition. Parents and patients must both be counseled on the risks and expected benefits of surgical correction.

PREOPERATIVE PLANNING

PREOPERATIVE PLANNING

The most important factor in preoperative consideration is the severity of the deformity, usually quantified by the Haller index. It can be determined from a standard AP and lateral chest radiograph. It is defined as the ratio of the transverse diameter (the horizontal distance of the inside of the thorax) and the anteroposterior diameter (the shortest distance between the anterior aspect of the vertebrae and the posterior aspect of the sternum). A normal Haller index should be about 2.5. Depression of the sternum will increase the index. A Haller index of 3.25 or greater is the usual cutoff for consideration of surgery.

Additional evaluation can include an electrocardiogram, echocardiogram, and/or pulmonary function tests, at the surgeon’s discretion. These evaluations may be required to define the extent of the physiologic abnormality and to exclude other pathologic processes.

Another factor that must be considered is patient age. This may impact both physical and psychological concerns. Correction of pectus excavatum at a young age, before relative skeletal maturity, may lead either to a recurrence of the deformity during the pubertal growth spurt or development of a constricting deformity of the chest wall resulting from impaired chest wall growth. It is recommended to proceed with repair after the onset of puberty to avoid these problems. Psychological maturity must also be evaluated to ensure that the rigors of postoperative pain management, hospital stay, and activity restrictions are understood and adhered to.

SURGERY

SURGERY

The Open “Ravitch” Procedure

The current standard open repair is attributed to Ravitch although his initial description included the resection of the costal cartilage and the perichondrium with anterior fixation of the sternum with Kirschner wires. Welch and Baronofsky in subsequent reports stressed the vital importance of preservation of the perichondrium to achieve optimal regeneration of the costal cartilage after repair.

Positioning

The patient is placed supine on a well-padded table. Lower body Bair Huggers are used to help maintain normothermia.

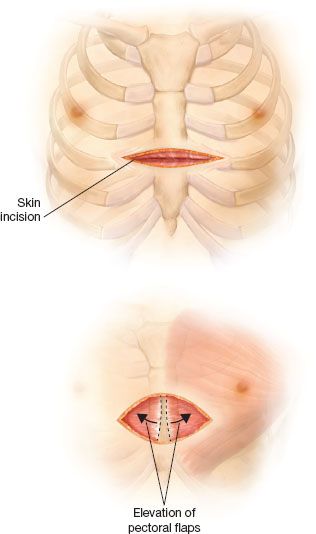

A transverse incision is made below and between the nipple lines. In females, particular attention is taken to place the incision within the projected inframammary crease thus avoiding complications of breast deformity and development. The pectoralis major muscle is elevated from the sternum along with portions of the pectoralis minor and serratus anterior bundles (Fig. 14.1).

A transverse incision is made below and between the nipple lines. In females, particular attention is taken to place the incision within the projected inframammary crease thus avoiding complications of breast deformity and development. The pectoralis major muscle is elevated from the sternum along with portions of the pectoralis minor and serratus anterior bundles (Fig. 14.1).

Figure 14.1 Location of the incision and initial mobilization of the pectoral muscle flaps.

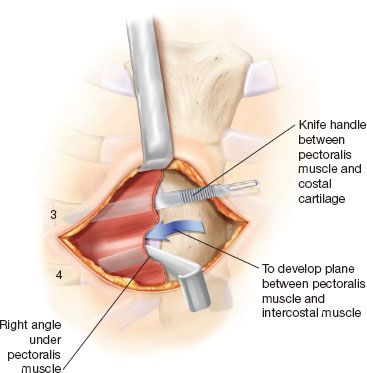

Figure 14.2 Creation of a plane between the pectoral muscle flaps and the chest wall.

The correct plane of dissection of the pectoralis muscle flap is defined by passing an empty knife handle directly anterior to a costal cartilage after the medial aspect of the muscle has been elevated with electrocautery. The knife handle is then replaced with a right-angle retractor, which is pulled anteriorly. The process is then repeated anterior to an adjoining costal cartilage. Anterior distraction of the pectoral muscle during the dissection facilitates identification of the avascular areolar plane and avoids entry into the intercostal muscle bundles (Fig. 14.2).

The correct plane of dissection of the pectoralis muscle flap is defined by passing an empty knife handle directly anterior to a costal cartilage after the medial aspect of the muscle has been elevated with electrocautery. The knife handle is then replaced with a right-angle retractor, which is pulled anteriorly. The process is then repeated anterior to an adjoining costal cartilage. Anterior distraction of the pectoral muscle during the dissection facilitates identification of the avascular areolar plane and avoids entry into the intercostal muscle bundles (Fig. 14.2).

Elevation of the pectoral muscle flaps is extended bilaterally to the costochondral junctions of the third to fifth ribs and a comparable distance for ribs six and seven or to the lateral extent of the deformity.

Elevation of the pectoral muscle flaps is extended bilaterally to the costochondral junctions of the third to fifth ribs and a comparable distance for ribs six and seven or to the lateral extent of the deformity.

Subperichondrial resection of the costal cartilage. The objective of this step is the removal of the costal cartilage connecting the ribs to the sternum, while leaving the perichondrial sheath in place. The cartilage removal will allow mobilization of the sternum, and the remaining sheath will act as a conduit for rib regeneration after the repair. The resection is achieved by incising the perichondrium anteriorly between the intercostal muscles (Fig. 14.3). The perichondrium is then dissected away from the costal cartilages in the bloodless plane between perichondrium and the costal cartilage. Cutting back the perichondrium 90 degrees in each direction at its junction with the sternum facilitates visualization of the back wall of the costal cartilage (Fig. 14.3).

Subperichondrial resection of the costal cartilage. The objective of this step is the removal of the costal cartilage connecting the ribs to the sternum, while leaving the perichondrial sheath in place. The cartilage removal will allow mobilization of the sternum, and the remaining sheath will act as a conduit for rib regeneration after the repair. The resection is achieved by incising the perichondrium anteriorly between the intercostal muscles (Fig. 14.3). The perichondrium is then dissected away from the costal cartilages in the bloodless plane between perichondrium and the costal cartilage. Cutting back the perichondrium 90 degrees in each direction at its junction with the sternum facilitates visualization of the back wall of the costal cartilage (Fig. 14.3).

The cartilages are sharply divided at their junction with the sternum as a Welch perichondrial elevator is held posteriorly to elevate the cartilage and protect the mediastinum (Fig. 14.4). The divided cartilage can then be held with an Allis clamp and elevated. The costochondral junction is preserved by leaving a segment of costal cartilage on the osseous ribs by incising the cartilage with a scalpel. Costal cartilages three through seven are generally resected, but occasionally the second cartilages must be removed as well. Segments of the sixth and seventh costal cartilages are resected to the point where they flatten to join the costal arch. Familiarity with the cross-sectional shape of the medial ends of the costal cartilages facilitates their removal. The second and third cartilages are broad and flat, the fourth and fifth are circular, and the sixth and seventh are narrow and deep.

The cartilages are sharply divided at their junction with the sternum as a Welch perichondrial elevator is held posteriorly to elevate the cartilage and protect the mediastinum (Fig. 14.4). The divided cartilage can then be held with an Allis clamp and elevated. The costochondral junction is preserved by leaving a segment of costal cartilage on the osseous ribs by incising the cartilage with a scalpel. Costal cartilages three through seven are generally resected, but occasionally the second cartilages must be removed as well. Segments of the sixth and seventh costal cartilages are resected to the point where they flatten to join the costal arch. Familiarity with the cross-sectional shape of the medial ends of the costal cartilages facilitates their removal. The second and third cartilages are broad and flat, the fourth and fifth are circular, and the sixth and seventh are narrow and deep.

Once the costal cartilages are all separated from the sternum, a sternal osteotomy is created at the level of the posterior angulation of the sternum (Fig. 14.5

Once the costal cartilages are all separated from the sternum, a sternal osteotomy is created at the level of the posterior angulation of the sternum (Fig. 14.5

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree