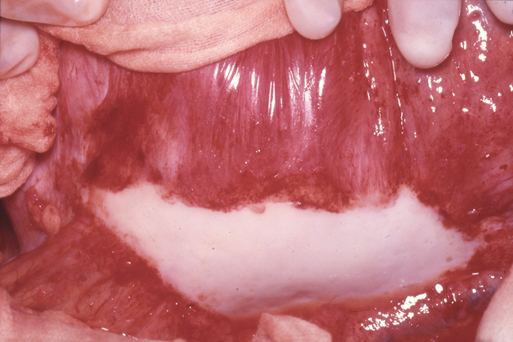

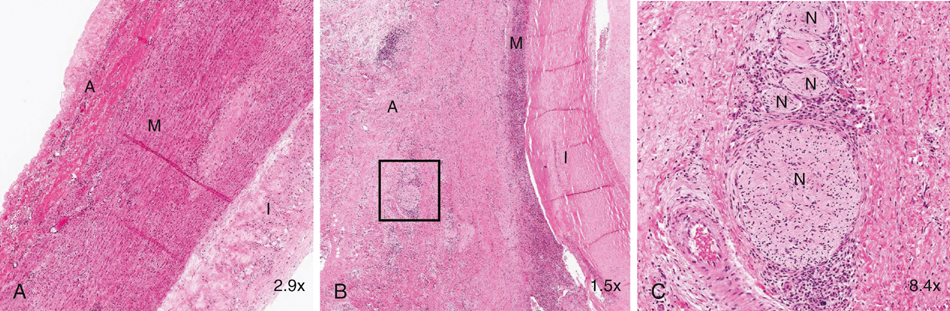

Inflammatory aneurysms are characterized by a pearly white thickened, highly vascular outer layer with dense localized adhesions to surrounding structures, most often the duodenum, inferior vena cava, left renal vein, and ureters. Any adjacent structure can be involved (Figure 1). It is these abundant unnatural bonds that make the operative approach for an inflammatory AAA more difficult than for a typical open AAA repair and has led many to suggest alternative surgical techniques such as minimal dissection of the duodenum off the aneurysm, retroperitoneal approach, or, more recently, endovascular exclusion. The aneurysmal wall thickening is predominantly located in the anterolateral locations with posterior sparing. Microscopically, inflammatory aneurysms are similar to AAA in regard to advanced atherosclerotic changes in the intima and marked medial thinning with degeneration of elastin and loss of smooth muscle cells. The adventitial surface is where the two types of aneurysms differ. The adventitia is markedly thicker (1–4 cm) in inflammatory aneurysms, with extensive fibrosis and a chronic inflammatory infiltrate including plasma cells, histiocytes, lymphoid follicles with germinal centers, and granulomas. This inflammatory reaction also involves the medial layer, and it can contain eosinophils as well as areas of periaortic phlebitis, endarteritis of the vasa vasorum, and perineural inflammation; these changes have rarely been described in typical AAA (Figure 2). Some have noted that the histology mimics that of Takayasu’s arteritis or giant cell arteritis when taken out of clinical context. These histologic findings involving the aortic wall are continuous with identical inflammatory findings in the retroperitoneal space.

Pathogenesis of Inflammatory Aortic Aneurysms

Pathology

Thoracic Key

Fastest Thoracic Insight Engine