Fig. 26.1

Schematic of the PDA murmur. Between S1 and S2, the murmur gradually becomes more audible. In contrast, between S2 and S1, the murmur gradually becomes less audible. These findings are consistent with the classic crescendo-decrescendo murmur found in PDA

Test Results

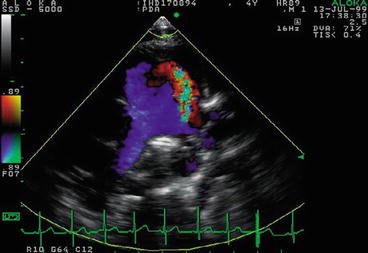

Echocardiography showed PA enlargement, LA/LV volume overload, and a wall hugging color flow jet at the bifurcation coursing down to the pulmonic valve (Fig. 26.2).

Fig. 26.2

Echocardiographic findings of a PDA: a color flow jet at the bifurcation coursing down to the pulmonic valve

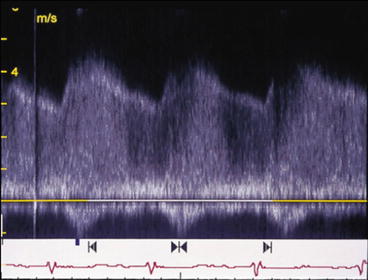

Doppler showed a continuous, high velocity jet exceeding up to 4 m/s (Fig. 26.3). Mild pulmonary hypertension was present.

Fig. 26.3

Doppler of PDA

Clinical Basics

Normal Ductal Anatomy (Fig. 26.4)

Fig. 26.4

During embryogenesis and in PDA, the ductus arteriosus joins the pulmonary circulation to the systemic circulation via a direct connection between the pulmonary artery and the aorta

The ductus arteriosus leaves the main pulmonary artery at its junction with the left pulmonary artery and continues posteriorly to reach the descending aorta about 5–10 mm distal to the origin of the left subclavian artery.

It functions to divert up to 55 % of the cardiac output of the right ventricle away from the high resistance pulmonary circulation to the low resistance umbilical-placental circulation.

Its patency is physiologically preserved in the neonatal period due to low P02, local prostaglandins, and local nitric oxide release [2].

Functional Closure [2]

Typically occurs within 24 h of birth.

Physiologic mechanisms include: (1) smooth muscle constriction, (2) reduced pulmonary vascular resistance due to lung expansion (3) increasing oxygen tension (4) reduced prostaglandin levels.

Anatomic Closure [2]

Typically occurs within 2–3 weeks of birth to form the ligamentum arteriosum.

Physiologic mechanisms include: (1) medial hypoxia (2) smooth muscle cell death (3) endothelial cell proliferation stimulated by hypoxic induced growth factor release (4) intimal thickening and fibrosis.

Differential Diagnosis for Patency

Premature birth.

High altitude.

Congenital Rubella.

Concurrent Congenital Heart Disease: In patients with other CHDs, about 15 % also present with PDA [2].

Coarctation of the Aorta.

PDA is observed in 2/3 of patients.

However, the presence of a large PDA can lower the accuracy of diagnosis of a coarctation, leading to significant morbidity and mortality [3].

The blood pressure differential normally observed between the upper and lower limbs is partially alleviated by the ductal shunt.

Echocardiographic Doppler diagnosis is diminished due to the amelioration of high velocity flow across the coarctation by the ductus [4].

Interrupted aortic arch.

Presence of PDA is essential for systemic perfusion.

The absence of a PDA is associated with a 90 % mortality rate in the first month without surgical correction [5].

Hypoplastic Left Heart Syndrome.

Systemic perfusion is dependent on a PDA and ASD.

Mortality approaches 95 % within the first month if the ductus does not remain patent.

Transposition of the Great Arteries [6].

PDA is observed in 2/3 of patients.

Patency is essential for survival in the pre-operative period, with a 60 % mortality rate in the first 6 months.

PDA Morphological Classification (Fig. 26.5a–e)

Fig. 26.5

(a–e) Illustration of morphological classification of PDA according to principles in Krichenko et al. [16]

The different morphological variants of a PDA have been categorized according to the Krichenko system of angiographic classification.

Angiographic classification is the current basis for determining whether the patent ductus can be closed via catheterization.

Referring to Fig. 26.5a–e:

Type A or Conical: well defined aortic ampulla and constriction near the pulmonary artery end.

Type B or Window: wide and short ductus that yields no demarcation between the aortic and pulmonary end.

Type C or Tubular: long tubular duct without constriction.

Type D or Complex: multiple constrictions.

Type E or Elongated: long with remote constriction from the anterior edge of the trachea.

Etiology

Hypothesized to be partial replacement of the smooth muscle cells in the media of the ductus by collagen and elastic fibers [2].

Most well-known cause of PDA is premature birth.

While there appears to be no clear genetic cause, the following genetic abnormalities have been associated with PDA [7]:

Trisomy 21.

4p syndrome, also known as Wolf–Hirschhorn syndrome (WHS), Pitt-Rogers-Danks syndrome (PRDS), or Pitt syndrome.

Carpenter’s syndrome.

Holt-Oram syndrome.

incontinentia pigmenti.

Char syndrome.

Genetic influences in PDA appear to be inherited in an autosomal recessive pattern with incomplete penetrance. Siblings have a 3 % rate of concordance in PDA [7].

Natural History

The natural history of PDA can include long-term, morbidity-free survival.

For those over the age of 20, infective endocarditis is the most common adverse event, followed by left ventricular consequences, then right ventricular abnormalities.

Signs and Symptoms

The findings on imaging and laboratory analysis show wide variation in concordance with the degree of shunting present.

The determined size and magnitude of the shunt can then be utilized to better elucidate the natural course and likely symptomatology of an unrepaired shunt.

Physical exam findings:

Hyperdynamic precordium.

Bounding pulses.

Wide pulse pressure >20 mmHg.

Tachycardia.

Chest.

Clear to auscultation.

Chest X-Ray.

Small Shunt – normal chest x-ray.

Large Shunt:

Left atrial and ventricular enlargement.

Increased pulmonary vascular markings in older children and adults.

Cardiac palpation may reveal:

Subtle dull impulse at right upper sternal border

Intermittent, palpable P2

Prevalence

The frequency of PDA ranges from 1 in 2000 to as high as 1 in 500 births and comprises 5–10 % of congenital heart diseases [2].

Appears to be a female predilection.

Key Auscultation Features

“Machinery-like,” crescendo-decrescendo murmur at left upper sternal border, in the second and third intercostal spaces [8].

The continuous murmur of PDA peaks at or just before S2.

Earlier peak indicates greater PDA flow.

The murmur will be loudest at the 2nd left intercostal space, greater than the first intercostal space.

Other features include that S2 may be paradoxically split, and a diastolic mitral murmur may be audible from high flow across the mitral valve.

Variations:

In premature infants, the murmur is primarily systolic; continuous murmurs are rarely heard [8].

With increasing size of shunt (usually in older patients), the murmur becomes louder and more prolonged, extending into diastole [8].

Auscultation examples of PDA.

Click here to listen to an example of a PDA with a long diastolic component, continuous murmur, and view an image of the phonocardiogram (Video 26.1).

Click here to listen to an example of a PDA with a short diastolic component, more typical of PDA, and view an image of the phonocardiogram (Video 26.2).

Clinical Clues to the Detection of the Lesion

When detected, other findings can be helpful:

EKG [7]:

Small shunts – normal.

Moderate-large shunts – left ventricular hypertrophy, left atrial enlargement, sinus tachycardia.

Echocardiography [7]: Echocardiography is the gold standard for definitive diagnosis.

Findings.

General: pulmonary artery enlargement, left atrial and left ventricular overload.< div class='tao-gold-member'>Only gold members can continue reading. Log In or Register to continue

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree