Parapneumonic Empyema

Lei Yu

Mark J. Krasna

Empyema is defined as accumulation of pus in the pleural space. Pus is thick, viscous fluid that appears to be purulent. Para- pneumonic effusion is any pleural effusion secondary to pneumonia (bacterial or viral) or lung abscess. It has been reported that 57% of hospitalized patients with bacterial pneumonia had an accompanying pleural effusion.13,14,28 While most parapneumonic effusions resolve without specific therapy, approximately 10% will become complicated or progress to empyema.15 Parapneumonic empyema may be localized, or it may involve the entire pleural cavity. The morbidity and mortality rates in patients with pneumonia and pleural effusions are higher than in patients with pneumonia alone.7

Pathogenesis

According to the 1962 classification of the American Thoracic Society for empyema,2 the evolution of parapneumonic empyema can be classified into three phases based on the natural history of the disease. The first stage is the exudative stage, in which a rapid outpouring of fluid into the pleural space occurs. Most of this outpouring is due to an increase in the amount of pulmonary interstitial fluid that traverses the pleura to enter the pleural space, but some of it stems from the increased permeability of the capillaries in the pleural space. The pleural fluid at this stage is characterized by negative bacterial studies, a glucose level above 60 mg/dL, a pH above 7.20, and a lactic acid dehydrogenase (LDH) level of less than three times the upper limit of normal in serum. If the patient fails to get proper treatment, the effusion may proceed to the second, or fibropurulent, stage. The pleural fluid at this point is characterized by positive bacterial studies, a glucose level below 60 mg/dL, a pH below 7.20, and a pleural fluid LDH more than three times the upper limit of normal for serum. Now the pleural fluid becomes infected and progressively loculated. If a stage 2 effusion is not drained, the effusion may progress to the third stage, in which fibroblasts grow into the pleural fluid from both the visceral and parietal pleurae, producing a thick pleural peel. The peel over the visceral pleura prevents the lung from expanding.

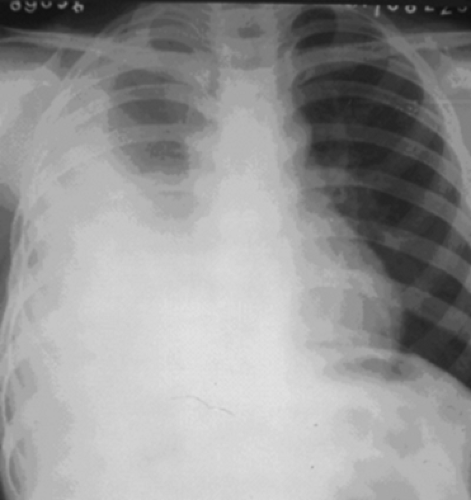

Parapneumonic empyema may also be divided into acute and chronic stages, depending on the duration of disease (Figs. 61-1 and 61-2). Although there is no definite division between the two, some authors claim that an empyema that has been present for 6 weeks or more is in the chronic phase. Acute parapneumonic empyema ordinarily results from a primary pneumonic process in the underlying lung, such as lobar pneumonia, pneumonitis, or lung abscess. These infectious diseases can directly extend into the pleura by way of the lymphatics, by hematogenous spread, or by rupture of necrotic pulmonary parenchyma. A combination of pleural dead space, a culture medium of pleural fluid, and inoculation of deposited bacteria produces empyema. Chronic empyema is due to untreated or inadequately treated acute empyema. Empyema necessitans (Fig. 61-2), an encapsulated empyema discharging into the subcutaneous tissues of the chest wall, is now rarely reported but still may occur.

Bacterial Etiology

The bacterial etiology of empyema has changed over the past several decades. According to Ehler,12 Streptococcus and Pneumococcus were the organisms most frequently associated with paraempyema. After the introduction of antibiotics, the incidence of empyema from these organisms was markedly reduced, as was the mortality rate. Staphylococcus became much more prevalent, and in the 1950s and 1960s, Ravitch and Fein21 found that this organism was cultured in 92% of patients under 2 years of age. Bartlett and colleagues3 reported that of 83 patients with positive pleural fluid cultures, 35% had anaerobic organisms exclusively, 24% had only aerobic organisms, and 41% had a combination of anaerobes and aerobes. In more recent times, as pointed out by Varkey and associates31 and Bergeron,5 penicillin-resistant Staphylococcus, gram-negative bacteria, and anaerobic organisms have been the predominant microbes. Alfageme and associates1 noted the increasing number of patients, particularly alcoholics, with staphylococcal empyema. Eastham and colleagues11 performed routine bacterial cultures of blood and pleural fluid for 47 cases; they found 32 (75%) pneumococcal culture–negative specimens to be pneumococcal DNA–positive. Pneumococcus remains the major pathogen in childhood empyema.

Clinical Presentation

The symptoms of parapneumonic empyema are not specific and may be difficult to distinguish from those of pneumonia or lung abscess. The clinical presentation depends on the causative organism, the volume of pus in the pleural space, and the patient’s circumstances. Patients often complain of cough, fever, chills, pleuritic chest pain, and even dyspnea, which are similar to the clinical features of pneumonia. Persistent fever in a

patient whose pneumonic process has resolved may be evidence of parapneumonic empyema. Physical examination reveals decreased respiratory excursion, pain on percussion, and a friction rub or distant to absent breath sounds on auscultation of the involved side. Weight loss and anemia are common with a chronic course.4 The parapneumonic empyema may erode into a bronchus to form a bronchopleural fistula, causing a chronic cough with copious foul-smelling sputum. This may also result in contamination of the central lung.

patient whose pneumonic process has resolved may be evidence of parapneumonic empyema. Physical examination reveals decreased respiratory excursion, pain on percussion, and a friction rub or distant to absent breath sounds on auscultation of the involved side. Weight loss and anemia are common with a chronic course.4 The parapneumonic empyema may erode into a bronchus to form a bronchopleural fistula, causing a chronic cough with copious foul-smelling sputum. This may also result in contamination of the central lung.

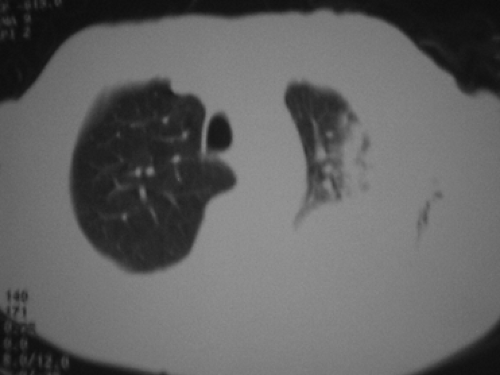

Posteroanterior and lateral chest films are likely to demonstrate the pleural abnormality—pulmonary consolidation with moderate pleural effusion or total opacity of one hemithorax. Ultrasound and CT scanning are helpful in differentiating consolidation and fluid accumulation in an opacified chest, especially in identifying complex, multiloculated empyemas that may require surgical drainage.

Diagnosis

Prompt detection and accurate characterization of a parapneumonic effusion are important. Based on the clinical presentation and a chest radiograph, the diagnosis of parapneumonic empyema is not difficult. Thoracentesis should be performed and aspiration of pus from the pleural space can help to confirm the diagnosis. Sometimes ultrasound or computed tomography CT is needed to guide the performance of needle aspiration. With concurrent antibiotic use, pleural fluid cultures may fail to grow in 50% of patients. If cultures are repeatedly sterile and the patient fails to improve with therapy, empyema secondary to tuberculosis or fungal infection should be suspected. Further examination of the pleural fluid is necessary to properly categorize the effusion.

CT scanning and bronchoscopy may help to distinguish between lung consolidation or atelectasis and pleural fluid and rule out the possibility of the pneumonic process secondary to bronchial obstruction due to bronchogenic carcinoma. Pleural empyema must be differentiated from an intrapulmonary abscess. An empyema conforms to the shape of the adjacent chest wall, while an abscess in the lung is usually more spherical, does not extend to or conform with the chest wall, and is surrounded by the pneumonia in which it developed.

Collected data should include patient demographics, size of the effusion, and microbiologic and pleural fluid chemistries that might influence the physician’s decision to place a chest tube or perform other therapeutic techniques. In the year 2000, a classification of parapneumonic effusions was developed by the American College of Chest Physicians on the basis of the anatomic characteristics of the fluid, the bacteriology of the pleural fluid, and the chemistry of the pleural fluid.8 This classification is shown in Table 61-1. According to it, parapneumonic effusions are divided into four categories conducive to making therapeutic strategies and predicting patient outcome.