Paraesophageal Hiatal Hernia

Keith S. Naunheim

Melanie Edwards

Classification of Hiatal Hernia

Hiatal hernias are generally classified into four types, the most common of which is the sliding or type I hiatal hernia. Hiatal hernia types II through IV are paraesophageal hernias, which vary with regard to the degree of intrathoracic migration as well as the contents of the hernial sac.

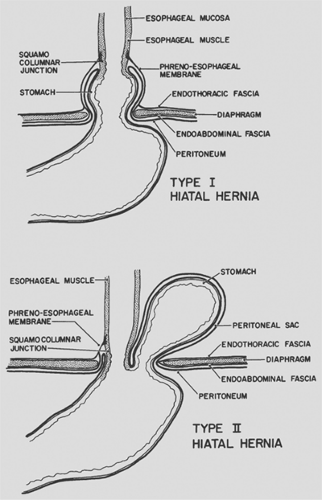

In order to appreciate the differences between the types of hernias, it is important to understand the anatomy of the hiatus and the gastroesophageal junction. The esophageal hiatus is formed by muscle fibers of the right crus of the diaphragm, with little or no contribution from the left crus. These fibers overlap inferiorly where they attach over and along the right side of the median arcuate ligament, which is attached to the lateral aspects of vertebral bodies. The orifice is therefore teardrop-shaped, with the point to the right of the aorta and the ventral rounded portion in the midline close to the connecting portion of the central tendon of the diaphragm. The crural fibers form a tunnel that encloses the esophagus. The phrenicoesophageal ligament is formed by fusion of the endothoracic and endoabdominal fascia at the diaphragmatic hiatus. This ligament inserts onto the esophagus just above the gastroesophageal junction circumferentially and holds the distal esophagus in place, with the most caudal 2 to 3 cm residing within the abdomen.

Type I

In the sliding type of hiatal hernia, the gastroesophageal junction moves upward through the diaphragmatic hiatus into the posterior mediastinum, so that it occupies an intrathoracic position and the proximal cardia resides within the chest. This process occurs because of circumferential weakening of the phrenicoesophageal ligament (Fig. 155-1). Factors that may contribute to the development of this hernia include increased abdominal pressure (e.g., with pregnancy, obesity, or vomiting) and vigorous esophageal contraction, which may pull the gastro- esophageal junction up into the mediastinum. This type of hiatal hernia is frequently accompanied by low resting pressure or inappropriate relaxation of the lower esophageal sphincter (LES), which may result in gastroesophageal reflux and esophagitis. The LES effects may be related to the loss of mechanical advantage at the gastroesophageal junction when it is displaced into the chest. The diagnosis and treatment of reflux esophagitis and type I hiatal hernia is reviewed elsewhere in this text.

Type II

The paraesophageal or type II hiatal hernia is an uncommon disorder that is distinct from the sliding hiatal hernia. In a para- esophageal hiatal hernia, the phrenicoesophageal membrane is not weakened diffusely but rather focally, anterior and lateral to the esophagus. The gastric cardia and lower esophagus remain at or below the diaphragm, while the gastric fundus and/or greater curvature protrudes or rolls through the defect into the mediastinum (see Fig. 155-1). The protruding organs are covered circumferentially by a layer of peritoneum that forms a true hernial sac.

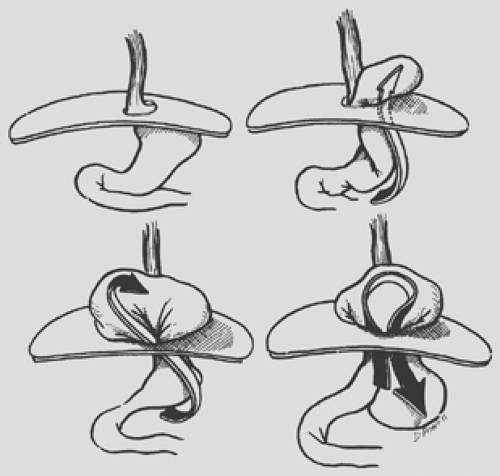

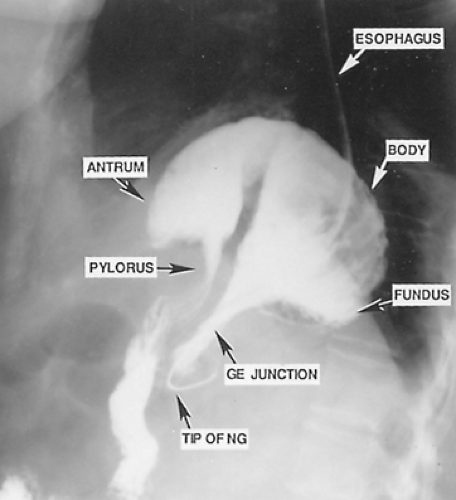

This intrathoracic migration of the stomach evolves by so-called organoaxial rotation (Fig. 155-2). The lesser curve of the stomach is anchored in the abdomen by the posterior attachments of the lower esophagus, the left gastric artery, and the retroperitoneal fixation of the pylorus and duodenum. These three points define the long axis of the stomach and remain relatively fixed within the abdomen in a type II hiatal hernia. The greater curve of the stomach, however, is relatively mobile and rotates about the “long axis” by moving first anteriorly and then upward as the hernia evolves. The fundus is the first part of the stomach to protrude upward through the anterior hernial sac. As the hiatal defect enlarges, the body and antrum continue the axial rotation and migrate into the thorax, leaving the cardia and pylorus in the abdomen. The stomach then resides “upside down” in the chest, with the remaining greater curve pointing cephalad and the cardia remaining at or below the diaphragm (Fig. 155-3). The stomach initially may occupy a retrocardiac position, but as the hernia enlarges, rotation occurs, usually into the right chest. With huge hernias, most of the stomach lies within the right hemithorax, and the greater curvature of the stomach points toward the right shoulder. The organoaxial rotation of the stomach is most commonly upward into the chest and toward the right. This is the path of least resistance because of the aorta to the left and the heart anterior into the left chest. Occasionally, however, the stomach may rotate directly in a superior direction without a rightward deviation, so that the greater curvature lies transversely behind the heart.

The term parahiatal hernia has been used in the past, but this type of defect may not actually exist. We have never encountered a defect in the diaphragm along the side of the esophageal hiatus with protrusion of the stomach into the chest and identifiable crural or diaphragmatic fibers separating the hernial orifice from the true hiatus.

Type III

The type III or mixed hiatal hernia is a combination of types I and II in that it includes both sliding and rolling components. If a type I hiatal hernia enlarges, the attenuated phrenicoesophageal membrane may also weaken focally in its anterior aspect and thus allow protrusion of the gastric fundus into the chest. Rotation of the stomach may result in the body or fundus obtaining a higher position within the chest than the cardia, but—unlike the type II hiatal hernia—in this situation the cardia itself is above the level of the hiatus.

It has also been suggested that a type III defect may very well be just progression or evolution over time of a type II defect. Presumably with ongoing negative intrathoracic pressure and positive intra-abdominal pressure, the severity of the gastric herniation may advance over the years until the cardia is drawn up above the level of the diaphragm, thus resulting in a type III defect. In this case, attachments of the gastroesophageal junction would remain intact posteriorly.

Type IV

Progressive enlargement of the diaphragmatic opening can eventually lead to herniation of organs other than the stomach into the chest. The transverse colon and omentum are most commonly involved, but the spleen and small bowel may also herniate into the chest. However, it is uncommon for patients to demonstrate obstructive symptoms from herniation of either large or small intestine into the chest in this setting.

Epidemiology

A paraesophageal hiatal hernia is far less common than the typical sliding hiatal hernia. Hill and Tobias,17 Ozdemir and colleagues,30 and Sanderud38 have reported that this condition accounted for only 3% to 6% of all patients undergoing surgical repair of hiatal hernias. Because most patients with hiatal hernia do not undergo operative repair, probably only 1% to 2% of all hiatal hernias are paraesophageal in type. Allen and colleagues1 reviewed the records of over 46,000 patients diagnosed with a hiatal hernia at the Mayo Clinic from 1980 to 1990. These investigators found that only 147 patients (0.32%) had paraesophageal hiatal hernias, with 75% or more of the stomach within the chest. Of the 124 patients who underwent operation, 51 (41%) had a type II hiatal hernia, 52 (43%) had a type III (mixed sliding and paraesophageal) hiatal hernia, and 21 (17%) had a type IV hiatal hernia with other organs identified within the intrathoracic hernial sac.

Symptoms

Some paraesophageal hiatal hernias cause few or no symptoms and remain undiagnosed for years until they are recognized on a routine chest radiograph or computed tomography (CT) scan performed often for another reason. In those patients with a supradiaphragmatic cardia, the LES may be incompetent; such patients can present with symptoms of gastroesophageal reflux, such as substernal burning and water brash. However, the most common symptoms result from the mechanical consequences of an intrathoracic stomach. As with any true anatomic hernia, potential complications include bleeding, incarceration, volvulus, obstruction, strangulation, and perforation. The most common symptoms overall are related to the obstructive nature of the paraesophageal hernia, with early satiety, postprandial pain, vomiting, and dysphagia being common complaints. In some patients, these symptoms may be insidious and not immediately apparent when a history is first taken. As a result of their symptoms, patients may gradually alter the pattern of their food intake to minimize or prevent postprandial discomfort. Thus decreased quantities of food are taken at increasingly longer intervals to minimize those symptoms that occur routinely during eating. Many patients who have been symptomatic for years or even decades will initially deny eating difficulties; it is only upon focused, persistent questioning of the patients and their family members that one finds that their oral intake has changed both in frequency and amount over a period of years, often with a concomitant weight loss.

Allen and associates1 documented the symptoms in the 147 patients undergoing a repair of a paraesophageal hiatal hernia and found that only 5% of their patients were asymptomatic. Postprandial pain occurred in 87 (59%), vomiting in 46 (31%), and dysphagia in 44 (30%). Gastroesophageal reflux was a complaint in only 23 patients (16%).

Bleeding is also a complication of paraesophageal hernia and most commonly occurs from the “saddle ulcers” found within the gastric wall at the level of the hiatus. It has been suggested that these may be purely a consequence of mechanical rubbing on the mucosa. Often patients will present not with acute bleeding but rather with chronic fatigue, and they may then be found to have anemia. This occurred in 21% of patients in the previously mentioned study of Allen et al.1 Bleeding is rarely rapid enough to result in melena, which the above authors found in three patients (2%).

Large type III or IV hiatal hernias may occupy a large portion of the thoracic cavity and result in postprandial respiratory symptoms of breathlessness with a sense of suffocation. Such symptoms, however, can also be mild, despite the presence of a huge hernia. Many patients have become accustomed to these symptoms and tolerate them well. They will sometimes describe this as a sensation of substernal fullness or pressure, and it can on occasion be mistaken for angina. This discomfort is frequently accompanied by nausea and may be somewhat relieved by belching or regurgitation.

The most feared complication of giant paraesophageal hernia is incarceration and/or strangulation. After a meal, the fundus may prolapse down from the hernial sac and back into the abdomen (see Fig. 155-2). This may twist and angulate the stomach in its midportion just proximal to the antrum, resulting in partial or complete obstruction. Distention of the intrathoracic stomach and further rotation of the fundus may result in obstruction at the gastroesophageal junction. Still further twisting may lead to pyloric obstruction, which results in an incarcerated gastric segment and a closed-loop obstructive physiology. If unchecked, this process ultimately leads to strangulation, necrosis, and perforation. Unless it is recognized and corrected, the resulting mediastinitis and shock may prove fatal. Such patients usually present in extreme distress and will often give a long history of complaints for which they may never have sought medical advice. The chief complaints at the time of presentation are severe pain and pressure in the chest or the epigastric region. The discomfort is usually accompanied by nausea and may be misdiagnosed as an acute myocardial infarction. Vomiting may occur, but more frequently the patient complains of retching and an inability to regurgitate. The patient may also complain of an inability to swallow saliva. If the volvulus is allowed to progress, strangulation of the intrathoracic portion of the stomach occurs, resulting in a toxic clinical picture including fever, third-spacing of a fluid, and hypovolemic shock. Borchardt5 originally described the constellation of substernal chest pain, retching with an inability to vomit, and the inability to pass a nasogastric tube; this triad of symptoms essentially is pathognomic for an intrathoracic gastric volvulus.

Fortunately this life-threatening complication occurs relatively infrequently today. In the past, it has been reported to occur more often. Hill and Tobias,17 Ozdemir,30 and Wichterman47 and their colleagues have reported that approximately 30% of their patients with paraesophageal hernias presented with gastric volvulus. However, Allen and colleagues1 reported only five such patients requiring emergency operations for suspected strangulation, an incidence of 3%. The reason for this may be that paraesophageal hernias are now recognized more frequently at an earlier stage. With the performance of routine chest x-rays and the wide dissemination of advanced radiologic testing such as CT and magnetic resonance imaging (MRI), the identification of asymptomatic or minimally symptomatic paraesophageal hernias has become a relatively frequent occurrence. Thus, patients who carry that diagnosis can undergo earlier surgical intervention, before obstructive symptomatology becomes severe. Finally, patients with large type IV hiatal hernias may occasionally become symptomatic because of the intrathoracic herniation of organs other than the stomach. It is rare to

identify obstructive symptoms primarily due to small intestinal or colonic compression secondary to intrathoracic herniation. Kafka21 has reported acute hemorrhagic pancreatitis in association with paraesophageal hernia because of herniation of the pancreatic head.

identify obstructive symptoms primarily due to small intestinal or colonic compression secondary to intrathoracic herniation. Kafka21 has reported acute hemorrhagic pancreatitis in association with paraesophageal hernia because of herniation of the pancreatic head.

Diagnosis

The diagnosis of paraesophageal hiatal hernia may often first be suspected because of an abnormal chest radiograph. The most frequent finding is a retrocardiac air bubble with or without an air-fluid level noted on the lateral view of a standard chest x-ray (see Fig. 155-3). In a giant paraesophageal hernia, the hernia sac and its contents occasionally protrude into the right thoracic cavity. The differential diagnosis includes mediastinal cyst or abscess and dilated obstructive esophagus, as one would see with megaesophagus in a patient with end-stage achalasia. A barium study of the upper gastrointestinal tract is usually diagnostic, with a pathognomonic finding being that of the upside-down stomach in the chest (Fig. 155-4). The radiologist should pay careful attention to the position of the cardia relative to the hiatus; this often requires lateral and/or oblique views during the performance of the swallow. This helps to differentiate between type II and type III hiatal hernias. A barium enema can help to determine whether any portion of the colon is involved; however, this is not strictly indicated in all patients, as it adds little or nothing to the decision-making process.

Both a CT scan and an MRI of the chest can suggest the diagnosis of paraesophageal hernia, but there is a little or no role for the routine utilization of such testing in the standard diagnostic workup.

Esophagogastroduodenoscopy (EGD) is now routinely performed in all patients in whom consideration of operative repair is entertained. The EGD allows for identification of the presence or absence of esophagitis, which may confirm a diagnosis of gastroesophageal reflux concomitant to the mechanical perturbations resulting from a paraesophageal hernia. This also allows for the identification of the potential presence of Barrett’s mucosa, a finding that not only indicates the presence of gastroesophageal reflux but also mandates long-term surveillance with follow-up EGD procedures. Finally, it is important to rule out unsuspected endoluminal causes of obstructive symptomatology, such as fibrotic stricture, esophageal neoplasm, or concomitant epiphrenic diverticulum. The typical endoscopic findings in an uncomplicated paraesophageal hernia are a somewhat serpiginous distal esophagus with a gastroesophageal junction at or above the level of a hiatus. That portion of the stomach which is supradiaphragmatic is twisted, and it may be difficult to traverse the entire length of the stomach into the pylorus due to this tortuosity. The EGD also allows for identification of intragastric ulcers, which may be the cause of the chronic anemia that many paraesophageal hiatal hernia patients have at presentation.

Controversy exists as to the role of preoperative esophageal function testing. Many surgeons routinely perform a preoperative esophageal manometry and 24-hour pH testing in order to help them decide whether or not a concomitant fundoplication at the time of hernia repair is indicated or contraindicated. Esophageal manometry tests, which can demonstrate severe esophageal dysmotility, can help the surgeon make an appropriate decision regarding whether to perform a fundoplication and if so what type of fundoplication (total or partial) would prove optimal. Manometry can also rule out concomitant esophageal dysmotility disorders, which can themselves result in dysphagia. Similarly, ambulatory 24-hour pH testing can help to identify gastroesophageal reflux, which is certainly best treated by a concomitant fundoplication at the time of surgical correction. Not all patients with the paraesophageal hernia actually have gastroesophageal reflux, although it can be a common finding. Walther and colleagues45 found pH testing consistent with pathologic reflux in 9 of 15 patients (60%) with type II hiatal hernias. Fuller and colleagues12 found similar evidence of reflux in 69% of their patients.

At our institution, patients referred with paraesophageal hernias routinely undergo EGD, 24-hour pH testing, and esophageal manometry to fully characterize the anatomic findings and physiology as well as any possible concomitant conditions. In this way, the surgeon obtains complete information regarding the anatomy and physiology of the lesion and can tailor the operative approach appropriately for each patient.

Decision for Surgery

For many decades the mere presence of a paraesophageal hiatal hernia was felt to be a strong indication for definitive repair. This belief stemmed from a report by Skinner and Belsey,40

who found a 29% mortality rate in 21 patients followed with nonoperative treatment. Similarly, Hill18 reported the outcomes of 29 patients with paraesophageal hernias, 10 of whom had developed incarceration. Two of the four patients operated on emergently died. The 50% operative mortality figure for emergent repair of incarcerated paraesophageal hernias has since been widely disseminated. Many surgeons have based their practice of immediate repair for paraesophageal hiatal hernias on these mortality figures, and this has been surgical dogma for nearly 30 years.

who found a 29% mortality rate in 21 patients followed with nonoperative treatment. Similarly, Hill18 reported the outcomes of 29 patients with paraesophageal hernias, 10 of whom had developed incarceration. Two of the four patients operated on emergently died. The 50% operative mortality figure for emergent repair of incarcerated paraesophageal hernias has since been widely disseminated. Many surgeons have based their practice of immediate repair for paraesophageal hiatal hernias on these mortality figures, and this has been surgical dogma for nearly 30 years.

However, it is highly likely that few if any of the patients in the mentioned series above were truly asymptomatic. Medical practice has changed significantly over the past four decades, and the identification of asymptomatic paraesophageal hiatal hernias is not uncommon. With the widespread dissemination of the use of barium swallows, CT, or MRI scans, and esophagoscopy for patients with even mild upper abdominal complaints, practitioners are now identifying paraesophageal hiatal hernias with little or no associated symptomatology.

The first investigators to suggest that such patients might be safely followed were Treacy and Jamieson.44 In their series, 29 of 71 patients were managed conservatively with a mean follow-up of 6 years. Thirteen of the conservatively managed patients developed progression of symptoms and eventually underwent surgical repair, although none required emergency inter- vention.

Similar experience was reported from the Mayo Clinic by Allen and coworkers.1 Of the 147 patients with paraesophageal hiatal hernia identified, 23 were followed nonoperatively and 19 of these were successfully managed in this fashion. Only four patients were noted to have progressive symptoms. They eventually underwent repair and one died of complications related to the hernia.

More recently, Stylopoulos and coinvestigators41 utilized a Markov Monte Carlo decision analytic model to determine the advisability of elective laparoscopic repair of paraesophageal hiatal hernias in patients with minimal or no symptoms. The analysis utilized conservative assumptions regarding operative mortality and postoperative hernial recurrence in order to predict the risk of developing acute symptoms that would require urgent surgery. These investigators compared the elective laparoscopic repair of paraesophageal hiatal hernias with a strategy of a watchful waiting. In nearly all age groups, the surveillance strategy proved to be an acceptable alternative. Their model suggests that at the age of 75, a patient had only a 12% risk of developing acute symptoms requiring emergency surgery. By the age of 85, this risk had decreased to less than 8%.

Thus many experts in this field have now come to recognize that all patients must be considered individually and that it is not appropriate to blindly recommend surgery for any and all patients presenting with paraesophageal hiatal hernia regardless of symptomatic presentation. Many such patients are septuagenarians or octogenarians with multiple comorbidities and relatively minor symptomatology. Such fragile patients are subject to relatively high rates of perioperative morbidity; therefore strong consideration should be given to expectant management, as most will live out their lives without serious incident due to their hiatal hernia.

However, in those patients with obstructive symptoms, there is no effective medical treatment that can adequately address most complaints. Although symptoms of reflux can often be effectively treated with proton pump inhibitors, most symptoms following meals will remain. In such patients operative therapy is indeed indicated.

Operative Principles

There is controversy regarding the optimal procedure to be performed as well as the optimal operative approach. However, there are certain tenets of operative management that are agreed upon by virtually all experts in the field. These principles include:

Reduction of the hernial sac’s contents

Removal of the hernial sac from the chest

Crural closure

Fixation of the stomach within the abdomen

Despite almost universal acceptance of these principles, there are some variations in the techniques utilized to achieve each of these goals.

Reduction of the Hernial Sac’s Contents

Although this is relatively easy to accomplish in the majority of patients, it can occasionally be difficult in those with a tight hiatal ring or with volvulus who have developed gastric distention with mural edema. In patients whose sac contents are difficult to extricate, excessive force should be avoided, lest serosal or full-thickness tears occur. Such tears, if unrecognized, can lead to perioperative leaks and the need for reoperation. It is important to achieve gastric decompression as effectively as possible with a nasogastric tube so as to maximize the chance of reducing the stomach into the abdomen without adjunctive maneuvers. It has been suggested that insertion of a soft red rubber catheter into the hernial sac with insufflation of a small amount of air may help facilitate reduction of the hernial contents by preventing a vacuum within the sac. For those patients in whom gentle traction and the tricks mentioned above are not effective, a small (1–2 cm) incision of the hiatus at the 12 o’clock position will usually make it possible to accomplish reduction.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree