21

Other Diffuse Lung Diseases

Bronchiolitis Obliterans with Organizing Pneumonia (BOOP)/Cryptogenic Organizing Pneumonia (COP)

Bronchiolitis obliterans with organizing pneumonia (BOOP), also called organizing pneumonia, refers to a nonspecific pattern of acute lung injury characterized by a distinctive form of patchy intraluminal proliferation of fibroblasts and myofibroblasts. BOOP occurs as a primary pathologic abnormality in a variety of clinical settings with multiple associations and potential etiologies (Table 21–1). Bronchiolitis obliterans organizing pneumonia was the term proposed in 1985 by Epler and colleagues for a unique clinicopathologic syndrome of idiopathic lung disease first described at the beginning of the 20th century in the German literature.1–3 Prior to Epler’s description other reports had used a variety of terms for the same syndrome, such as cryptogenic organizing pneumonitis,4 bronchiolitis obliterans with classical interstitial pneumonia (BIP),5 bronchiolitis obliterans,6 and organizing pneumonia-like process.7 Since 1985 still other synonyms have been offered, including proliferative bronchiolitis8 and idiopathic intraluminal organizing pneumonia.9 Using the modifier “idiopathic” is helpful in distinguishing idiopathic BOOP, a specific clinical entity, from the relatively nonspecific histologic lesion described below. A recently published classification scheme for the idiopathic interstitial pneumonias adopts the term cryptogenic organizing pneumonia (COP).10 Numerous reviews have summarized clinical, radiologic, and pathologic features of idiopathic BOOP.8,11–23

Clinical Features

Idiopathic BOOP is uncommon, with age- and sex-adjusted annual incidence of less than 1 per 100,021 person years in southeast Minnesota for the decade from 1984 to 1994.28 Adult men and women are affected equally, with a peak incidence in the sixth decade of life. Underlying connective tissue disease has been identified in less than 10% of reported patients.3,4,24,25,28,82,114–116 Most patients with idiopathic BOOP present with cough, often with associated shortness of breath, of several weeks’ duration. Fever accompanies the respiratory complaints in about half; malaise and weight loss are present in a minority of patients. A more fulminant course has been described in a few patients,113,117,118 although the clinical, radiologic, and pathologic findings overlap with those seen in acute interstitial pneumonia (Hamman-Rich disease) (see Chapter 20).119–121 The classical description has been expanded by recognition of seasonal variation in a subset of patients from the United Kingdom who develop respiratory illness from late February to early May (“seasonal cryptogenic organizing pneumonia”).122 Physical findings in the majority of patients are limited to tachypnea and fine inspiratory crackles. Digital clubbing is rare. Laboratory findings show inconsistent and nonspecific abnormalities including mild leukocytosis and mild elevation in erythrocyte sedimentation rate and C-reactive protein.4,28,115 Cholestatic abnormalities in liver function tests occur uncommonly, and have been linked to the seasonal variant.116,122 Pulmonary function studies typically show mild to moderate restriction of lung volumes accompanied by a diminished diffusion capacity for carbon monoxide (DLCO).

Connective tissue diseases | Mixed connective tissue disease24,25 Polymyositis/dermatomyositis24,27,28 Systemic lupus erythematosus24,28,32–34 |

Infection | Cryptococcus neoformans536 Human herpesvirus type 7 (HHV-7)37 Mycobacterium tuberculosis36 Nocardia asteroides40 Parainfluenza 3 virus42 Pneumocystis carinii36 |

Drug toxicity | Acebutolol43 Carbamazepine54 Cephalexin monohydrate Chloroquine and primaquine phosphate28 Chlorozotocin55 Cocaine56 Cromolyn sodium57 Cytosine arabinoside58 Hexamethonium62 Mecamylamine64 Mesalamine65 Methotrexate47 Minocycline66 Mitomycin67 Nilutamide68 Phenytoin sodium70 Sotalol73 Tocainide75 Transtuzumab (Herceptin)78 |

Potentially immunocompromised patients | Acquired immunodeficiency syndrome (AIDS)28,79 Bone marrow transplantation36,80–83 Common variable immunodeficiency84 Lymphoma/leukemia and myeloproliferative disorders28,36,80,82 Renal transplantation80 Solid organ malignancies36 |

External beam thoracic irradiation | Lung carcinoma92 |

Occupational exposures/inhalational injury | Silo filler’s disease (nitrous oxides)93–97 |

Inflammatory bowel disease | |

Vasculitic syndromes | Polyarteritis nodosa105 Wegener’s granulomatosis106 |

Miscellaneous | Anthrax vaccination107 Aspiration of activated charcoal108 Aspiration of gastric contents109 Immunoglobulin A (IgA) nephropathy110 Menses111 |

The terms BOOP and cryptogenic organizing pneumonia have also been applied to patients with underlying malignancies, most of whom received various forms of immunosuppressive therapy including patients status post–bone marrow transplantation.28,36,82 Although many reported patients have respiratory syndromes analogous to otherwise idiopathic illness, the term idiopathic BOOP should probably be avoided in patients with underlying malignancies and immunocompromised patients because their lung diseases are often related to infection or other iatrogenic factors.28,36 Most patients in this category survive their respiratory illnesses but have higher overall mortality rates compared with patients without underlying diseases.28,36

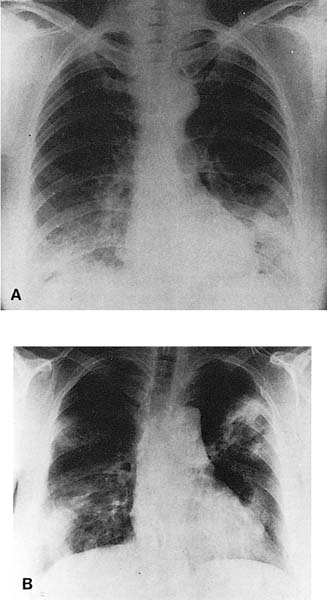

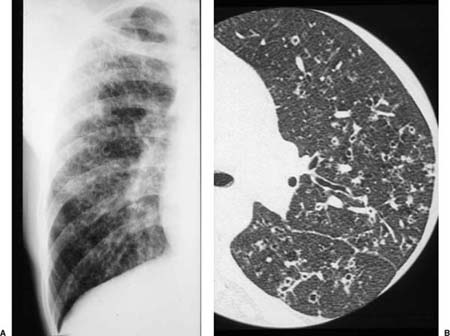

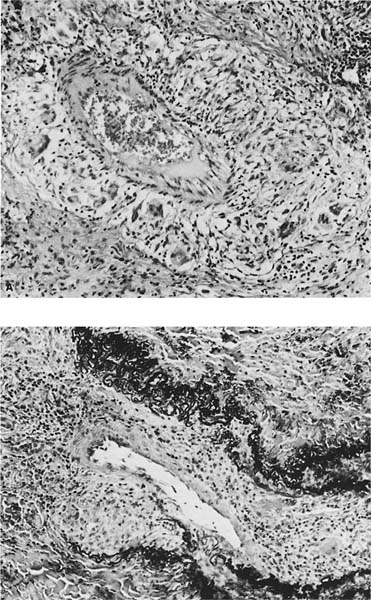

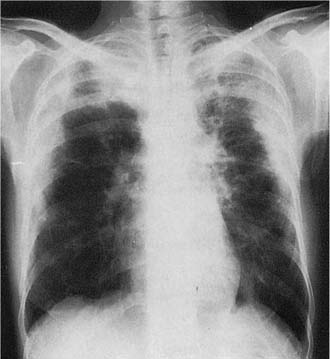

Radiologic abnormalities in patients with BOOP are heterogeneous. Conventional chest roentgenograms typically show patchy bilateral airspace opacities, often described as having a “ground-glass” or consolidated appearance (Fig. 21–1).3,21,123,124 The radiographic appearance is not specific and frequently mimics infectious pneumonia. Peripheral migratory infiltrates that tend to wax and wane over time are seen in some patients and overlap with radiographic findings classically associated with chronic eosinophilic pneumonia.115,123,125 Conventional computed tomography (CT) and high-resolution CT (HRCT) scans demonstrate patchy areas of consolidation or ground-glass opacity in a peribronchovascular or peripheral subpleural distribution (Fig. 21–2).126–130 Areas of opacity are often characterized as nodular or mass-like in appearance.129–131 Cavitation has been observed in only occasional patients and when present should raise concerns for other possibilities, such as infection, carcinoma, or Wegener’s granulomatosis.132–135 Localized airspace opacities represent another radiologic manifestation of idiopathic BOOP and may be indistinguishable from various lung neoplasms.28,132,136,137 Patients with localized opacities are usually asymptomatic without the nonspecific laboratory abnormalities more commonly observed in patients with patchy bilateral disease.28 Bibasilar interstitial opacities that mimic those seen in idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis are uncommon.114 This latter radiographic pattern may be more common in patients with associated collagen vascular diseases and tends to be associated with a poorer prognosis.114

FIGURE 21–1 Two cases of idiopathic bronchiolitis obliterans with organizing pneumonia shown radiographically. (A) Bilateral lower lobe infiltrates that cleared after steroid therapy. (B) Patchy bilateral infiltrates. (Courtesy of Dr. G. Epler, Boston.)

Clinical and radiologic features of idiopathic BOOP are characteristic but not specific. For that reason, lung biopsy is usually a key element in evaluation and diagnosis of patients with this syndrome. Surgical lung biopsy has been highlighted as the preferred diagnostic method,3,138 but transbronchial biopsies are also a reliable diagnostic tool if carefully interpreted in an appropriate clinical and radiologic context.116,123,139,140

The prognosis for patients with idiopathic BOOP is excellent, with disease-specific mortality rates of just over 6%.3,4,24,25,28,114–116 Corticosteroids are standard therapy, although some patients recover without treatment. Relapses are common and develop in over half of patients, most within the first year of the presenting episode.116 Risk of relapse increases with increasingly severe hypoxemia at presentation and delays in treatment initiation.116,141 Relapse often occurs after treatment cessation or with tapering low-dose therapy. Most patients who relapse respond to corticosteroid treatment.

Pathologic Features

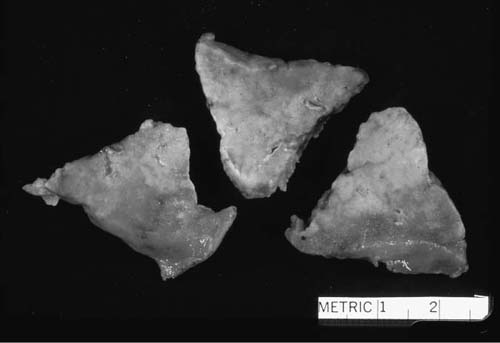

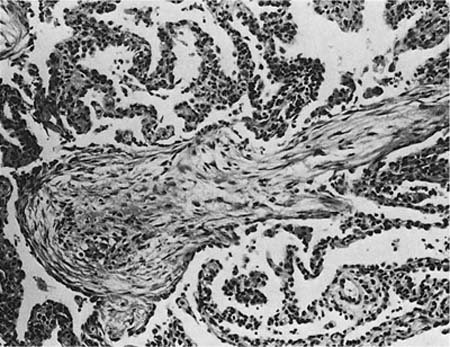

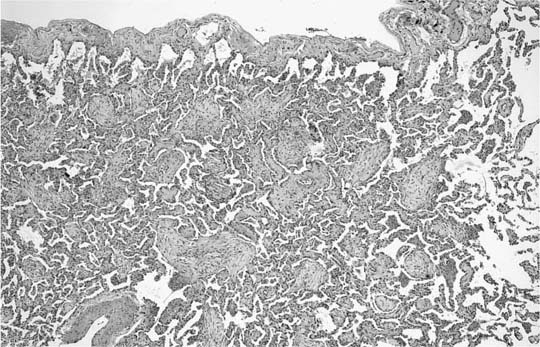

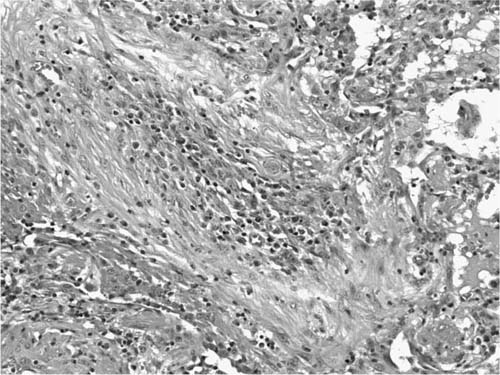

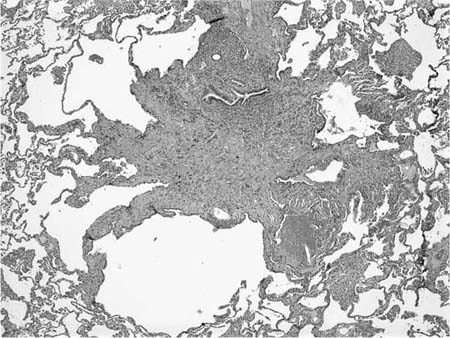

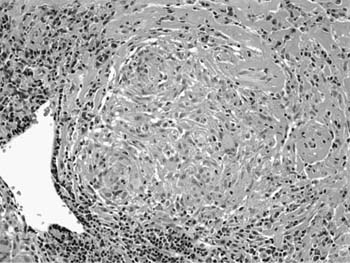

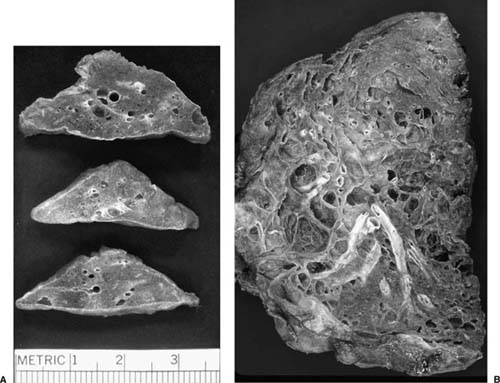

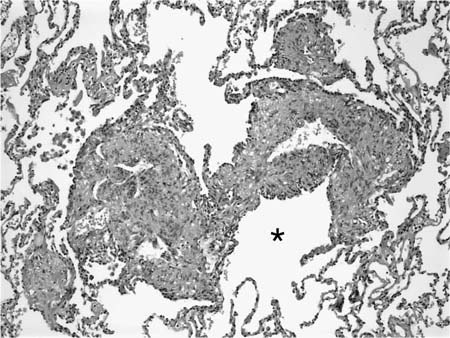

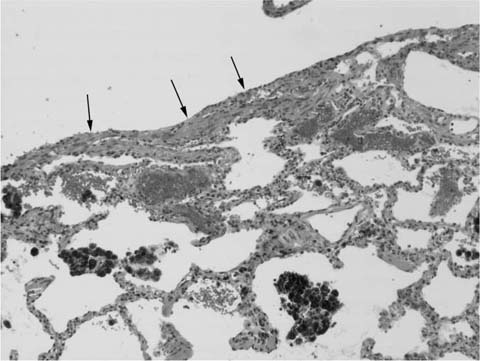

A distinctive pattern of intraluminal fibrosis involving distal airways, alveolar ducts, and peribronchiolar airspaces is the histopathologic abnormality that defines BOOP. Filling of airways and airspaces results in patchy consolidation (Fig. 21–3) corresponding to the findings described on imaging studies. The intraluminal fibrosis consists of polypoid intraluminal plugs of connective tissue rich in spindle cells (Fig. 21–4). Intraluminal fibroblastic plugs are distributed within distal airways and alveolar ducts, resulting in a characteristic low magnification appearance (Fig. 21–5). Larger terminal bronchioles and peribronchiolar alveolar spaces also show varying degrees of involvement. At higher magnification intraluminal fibrosis consists of concentrically arranged spindle cells associated with a pale-staining basophilic matrix (Fig. 21–6). Chronic inflammatory cells and capillaries may be present within areas of fibrosis, thus resembling granulation tissue. Fibrinous exudates may accompany the luminal fibrosis (Fig. 21–7). An acute and chronic bronchiolitis is often present away from the areas of airspace fibrosis and consists of a nonspecific peribronchiolar infiltrate of acute and chronic inflammatory cells.

FIGURE 21–2 Computed tomography scan from patient with idiopathic bronchiolitis obliterans with organizing pneumonia. Patchy areas of consolidation are present bilaterally with a peripheral subpleural distribution.

FIGURE 21–3 Photograph illustrating cut surface of surgical lung biopsy specimen involved by bronchiolitis obliterans with organizing pneumonia (BOOP). Patchy areas of pallor correspond to consolidated zones in which distal airways and peribronchiolar airspaces are filled by intraluminal fibrosis.

Fibrosis in the form of interstitial collagen deposition is distinctly uncommon in BOOP. The presence of collagen fibrosis, particularly when it is accompanied by architectural distortion in the form of scarring or honeycomb change, signifies a worse prognosis likely related to the presence of some other underlying process such as usual interstitial pneumonia.142,143

FIGURE 21–4 Photomicrograph showing intraluminal plug of fibroblastic tissue typical of BOOP. Spindle cells, comprising fibroblasts and myofibroblasts, are organized in a somewhat linear and whorled fashion within a pale-staining matrix. There is a scant associated infiltrate of mononuclear inflammatory cells. Neighboring alveolar septa are expanded by a nonspecific infiltrate of chronic inflammatory cells (i.e., interstitial pneumonia).

FIGURE 21–5 Low-magnification photomicrograph (original magnification ×40) illustrating characteristic appearance of BOOP. Polypoid plugs of connective tissue are distributed within respiratory bronchioles, alveolar ducts, and to a lesser extent alveolar spaces. Lung tissue in the right-hand portion of the field is uninvolved and demonstrates clusters of finely vacuolated alveolar histiocytes (“endogenous lipid pneumonia”) in adjacent airspaces.

Several secondary changes accompany the intraluminal fibrosis in BOOP. Foamy alveolar macrophages (“endogenous lipid pneumonia”) are present within peribronchiolar alveolar spaces and attest to the presence of proximal small airway dysfunction. Interstitial pneumonia is also present and is characterized by a nonspecific alveolar septal infiltrate of mononuclear inflammatory cells with associated epithelial hyperplasia. Interstitial pneumonia is limited to the areas of intraluminal fibrosis and is not present in unaffected pulmonary parenchyma, a helpful feature in distinguishing BOOP from conditions in which organizing pneumonia may be a secondary finding (see later in this chapter).

Differential Diagnosis

Bronchiolitis obliterans with organizing pneumonia, a term synonymous with organizing pneumonia, is a relatively nonspecific reaction to acute lung injury that can occur as a secondary finding adjacent to, or as a minor component of, other pathologic processes. This is particularly important to bear in mind when interpreting small biopsy specimens. For example, cryptococcosis (see Chapter 10), Wegener’s granulomatosis (see Chapter 15), eosinophilic pneumonia, and lung carcinoma are four important conditions in which organizing pneumonia can be a prominent secondary feature.36,106,135,144 Focal areas of organizing pneumonia resembling BOOP also occur frequently in nonspecific interstitial pneumonia (NSIP) and hypersensitivity pneumonia, and occasionally in other conditions such as usual interstitial pneumonia and Langerhans’ cell histiocytosis. Recognition of histopathologic features diagnostic of the underlying process is the key to distinguishing secondary organizing pneumonia from cases in which BOOP represents the primary pattern of injury.

FIGURE 21–6 Photomicrograph (original magnification ×200) showing mononuclear inflammatory cells and capillaries within a focus of intraluminal fibrosis in BOOP.

FIGURE 21–7 Photomicrograph of BOOP (original magnification ×100) showing BOOP with an associated fibrinous airspace exudate. The fibrinous exudates are intimately associated with intraluminal fibrosis and a minor complement of histiocytes and occasional neutrophils and eosinophils. This finding overlaps with features seen in certain infections as well as eosinophilic pneumonia but is compatible with a diagnosis of idiopathic BOOP, assuming an appropriate clinical context.

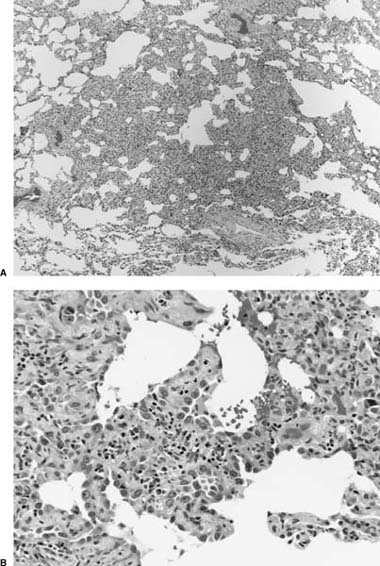

Diffuse alveolar damage in the organizing phase demonstrates significant morphologic overlap with BOOP, prompting Katzenstein145 to consider both under the general heading of acute lung injury patterns. Intraluminal fibrosis virtually indistinguishable from that seen in BOOP can occur as a focal or dominant finding in organizing diffuse alveolar damage (Fig. 21–8). Lung tissue away from areas of intraluminal fibrosis differs, however, in showing expansion and distortion of alveolar septa by fibroblasts and myofibroblasts often with associated hyaline membranes. Other markers of acute lung injury, such as fibrin thrombi in small muscular arteries and squamous metaplasia of bronchiolar epithelium, are uncommon in BOOP and when present should prompt a search for histologic features diagnostic of diffuse alveolar damage. In especially difficult cases correlation with clinical and radiologic findings is helpful in that diffuse alveolar damage typically occurs in the context of the acute respiratory distress syndrome (ARDS).

The term bronchiolitis obliterans has been applied to patients with BOOP as well as patients with a form of primary fibrosing airway disease now more commonly referred to as constrictive or obliterative bronchiolitis (see Chapter 22).146 Patients with this disorder more commonly have significant airflow limitation on pulmonary function tests and nearly normal radiologic findings. The pathologic changes consist of patchy and sometimes subtle peribronchiolar fibrosis that encroaches on airway lumina, eventually reducing them to collagenized scars. Constrictive bronchiolitis lacks the intraluminal fibrosis typical of BOOP.

Pathogenesis

Ultrastructural and immunohistochemical studies show significant morphologic overlap between BOOP and other forms of acute lung injury, mainly diffuse alveolar damage.147–150 Necrosis of bronchiolar, alveolar duct, and alveolar septal epithelium results in denudation of epithelial basement membranes. Fibroblasts migrate from the interstitial compartment into airways and airspaces through gaps in damaged basement membranes. Activated fibroblasts within areas of intraluminal fibrosis differentiate into myofibroblasts capable of collagen synthesis.151 Within airways and airspaces fibroblasts and myofibroblasts organize into compact connective tissue plugs composed of glycosaminoglycans, other matrix proteins, and inflammatory cells.148,149,151,152 Alveolar macrophage-derived interleukin-8 (IL-8), fibronectin, and platelet-derived growth factor (PDGF) may play important roles in migration and activation of fibroblasts and in recruitment of inflammatory cells including T lymphocytes and mast cells.153–156 Capillaries eventually populate the luminal connective tissue polyps. Proliferating reparative epithelial cells, mainly type 2 pneumocytes, eventually incorporate the polypoid plugs of intraluminal fibrosis back into the interstitial compartment where mechanisms not yet fully understood restore normal lung architecture.157

FIGURE 21–8 Photomicrographs depicting “BOOP-like” changes in organizing diffuse alveolar damage. (A) Intermediate-magnification (original magnification ×100) photomicrograph showing a pattern of intraluminal fibrosis indistinguishable from BOOP. (B) Photomicrograph (original magnification ×100) from same biopsy illustrated in A showing changes typical of diffuse alveolar damage including well-formed hyaline membranes.

Despite morphologic and phenotypic overlap between intraluminal fibrosis in BOOP and interstitial fibroblast foci in usual interstitial pneumonia (UIP) (see Chapter 20), there are also important differences that are likely key to differences in pathogenesis.158 Compared with fibroblast foci in UIP, areas of intraluminal fibrosis in BOOP demonstrate more orderly reepithelialization linked to differences in expression of various cytokines, cell cycle regulatory proteins, and extracellular matrix proteins.159–163 Matrix metalloproteinases (MMPs), particularly MMP-2, are expressed more commonly in BOOP and are associated with collagen fibril phagocytosis.164,165 Intraluminal fibrosis in BOOP is more highly vascularized than fibroblast foci in UIP related to differences in vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF) expression.166,167 Apoptotic activity within areas of fibroblast and myofibroblast proliferation is also higher in BOOP.168

Langerhans’ Cell Histiocytosis (LCH) (Eosinophilic Granuloma)

Pulmonary LCH, also termed pulmonary eosinophilic granuloma or Langerhans’ cell granulomatosis, is an interstitial lesion of uncertain etiology characterized by an abnormal proliferation of Langerhans’ cells. Although pulmonary LCH shares some histologic features with lung involvement in disseminated forms of childhood histiocytosis X, it differs clinically in that it occurs mainly in adults in whom pulmonary involvement is the sole or predominant manifestation of disease.

Clinical Features

Pulmonary LCH affects primarily young and middle-aged men and women with a peak incidence in the third and fourth decades. Nearly all reported patients have been former or current cigarette smokers, prompting many authors to consider LCH a form of smoking-related interstitial lung disease.169–171 Respiratory symptoms are common at presentation and include nonproductive cough and dyspnea. About a third of patients also have constitutional complaints such as fever, weight loss, night sweats, and anorexia.172–175 About one in four patients is asymptomatic at the time of diagnosis.173–175 Spontaneous pneumothorax is a commonly reported complication, but probably occurs in less than 25% of patients.176 A smaller percentage of patients experience symptoms secondary to extrapulmonary involvement, mainly isolated bone pain or diabetes insipidus. Pulmonary function studies are variable and may be normal or instead show mild airflow limitation, mild restriction, or a combination of the two.173–175,177–180 A reduced DLCO is the most consistent abnormality and is present in as many as 90% of patients.175 Patients with LCH may be at increased risk for developing pulmonary hypertension compared with other forms of diffuse lung disease.180,181

Several authors have noted a relationship between LCH and bronchogenic carcinoma, a relationship likely explained by a common risk factor (i.e., cigarette smoking) rather than true cause and effect.182–184 Patients with pulmonary LCH may be at increased risk for developing other extrapulmonary neoplasms, including hematologic malignancies.184,185

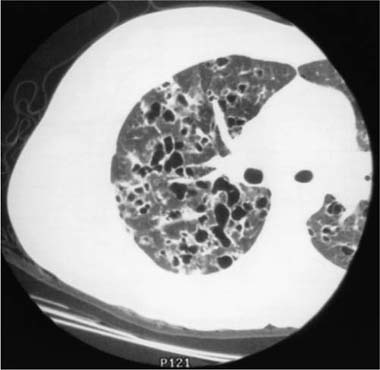

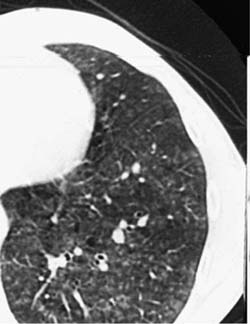

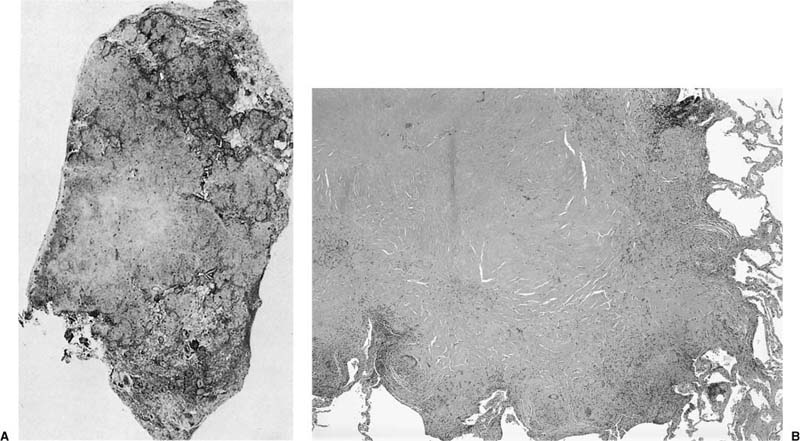

Conventional chest roentgenograms are nearly always abnormal at the time of diagnosis and show micronodular and reticulonodular opacities, with or without cystic (“honeycomb”) change, involving middle and upper lung zones with sparing of the costophrenic angles (Fig. 21–9).173,177,178,186,187 CT and HRCT show a combination of nodules, usually less than 10 mm in diameter, and thin-walled cysts involving predominantly middle and upper lung zones (Fig. 21–9).187–192 Cavitation within the nodules is uncommon.188,189,192 The centrilobular nodular opacities predominate in early disease, whereas thin-walled cysts are characteristic of more advanced stage disease (Fig. 21–10).188,189,191,192 Concomitant ground-glass attenuation is seen in some patients.193 This distinctive combination of findings allows a confident radiologic diagnosis in a high percentage of cases. Rarely reported manifestations of LCH include solitary macroscopic nodules, obstructing intratracheal or endobronchial tumors, and synchronous mediastinal lymph node involvement.194–198

The natural history of pulmonary LCH is difficult to predict and ranges from spontaneous regression to progressive respiratory insufficiency and death. Disease-specific mortality is between 10% and 20% with median survivals of about 13 years.185,199 Older age at diagnosis, significant airflow limitation with air trapping, and severely reduced DLCO may imply a worse prognosis.185,199 Smoking cessation is the mainstay of therapy and should be strongly encouraged in all affected patients.200,201 Corticosteroids are often used in symptomatic patients, but there is only limited anecdotal evidence of efficacy.202 Transplantation is a therapeutic option for patients with advanced disease, although LCH can recur within lung allografts.203

Pathologic Features

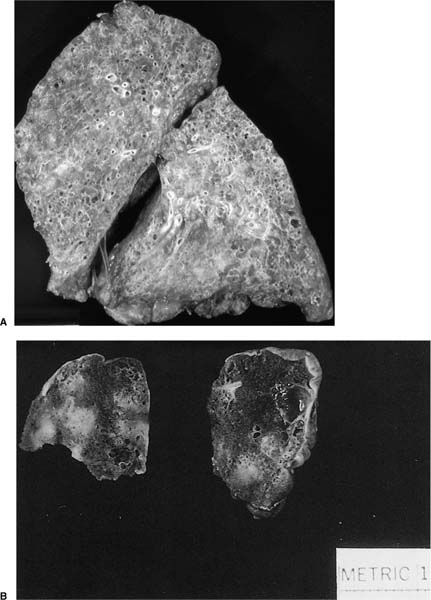

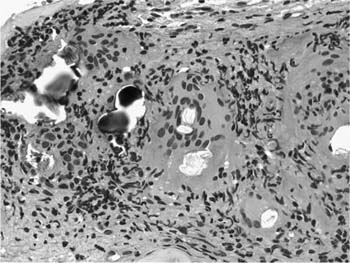

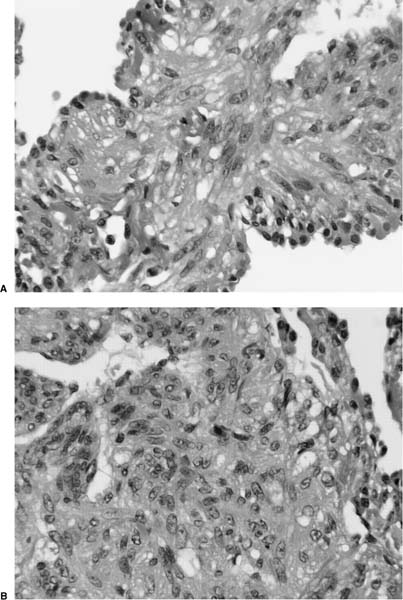

The gross appearance of lung specimens with LCH includes a combination of patchy nodular fibrosis and cystic change corresponding to the findings described on CT and HRCT scans (Fig. 21–11). In advanced disease, the extent of cystic change may rival that seen in emphysema, but the middle and upper lung zone distribution and the degree of associated fibrosis are helpful clues to the diagnosis.

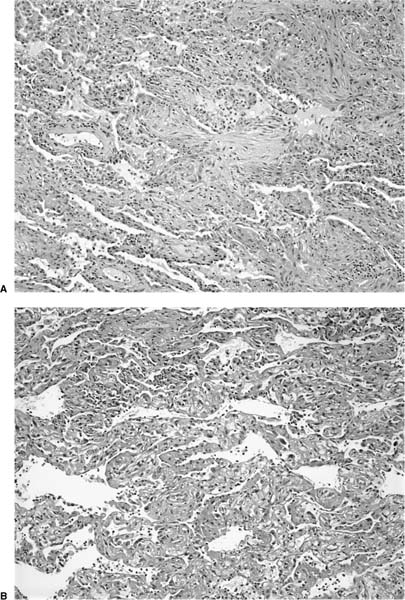

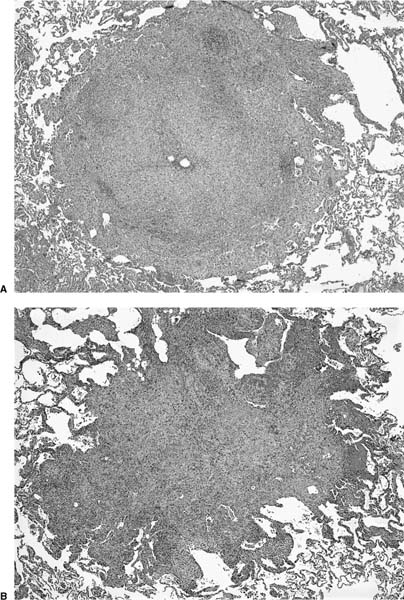

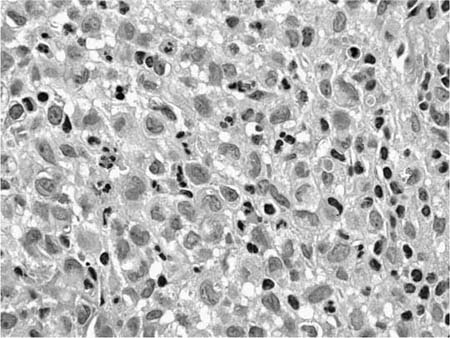

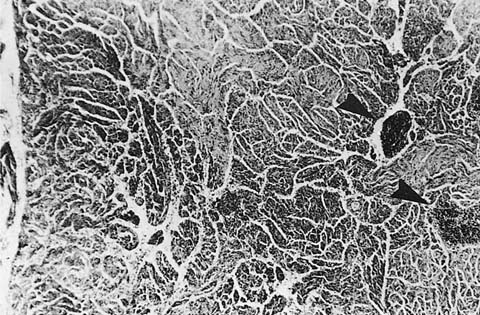

Microscopically, LCH comprises patchy interstitial nodules that often have a stellate configuration at low magnification (Fig. 21–12).172,173,177,178,204 The nodules are centered on bronchioles and occasionally show central cavitation corresponding to ectasia of the central airway lumen.204,205 At higher magnification, the nodules contain a mixed inflammatory infiltrate including eosinophils, lymphocytes, plasma cells, histiocytes, and histiocyte-like Langerhans’ cells amidst a variably fibrotic background (Fig. 21–13). The nodules are frequently fibrotic centrally, the most cellular zones being in the peripheral tentacles formed by peribronchiolar interstitium tethered to contiguous alveolar septa. Enlargement of adjacent airspaces (i.e., paracicatricial airspace enlargement) is common as the nodules become more fibrotic. Eventually nodules become completely fibrotic, leaving only stellate collagenized scars as testimony to the likely underlying diagnosis (Fig. 21–14).177,206

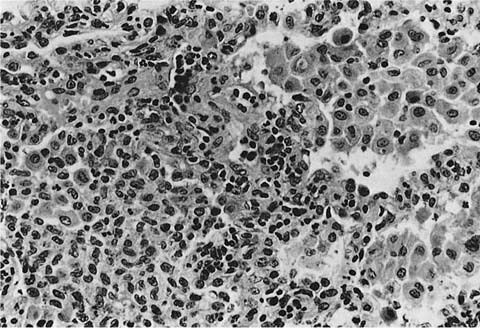

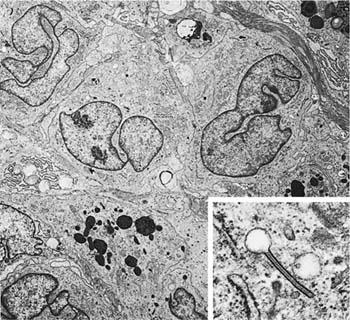

Accurate diagnosis of LCH hinges on recognition of Langerhans’ cells in the appropriate background. Abnormally increased numbers of Langerhans’ cells can occur in other pathologic conditions, but in other circumstances are usually distributed as single cells rather than the small groups, clusters, and sheets characteristic of LCH.207,208 Langerhans’ cells are distinguished by convoluted and folded nuclei with bland evenly dispersed chromatin, absent or inconspicuous nucleoli, and abundant pale-staining eosinophilic cytoplasm with indistinct borders (Fig. 21–15).209 The presence of highly convoluted nuclear contours is the single most helpful cytologic feature in distinguishing Langerhans’ cells from conventional histiocytes. Identification of Langerhans’ cells in the context of the previously described low-magnification features allows confident diagnosis of LCH on the basis of routinely stained sections in many cases. Immunohistochemical stains are helpful in difficult biopsies, particularly small transbronchial specimens.178,210 Langerhans’ cells stain with a variety of antibodies easily applied in routinely processed paraffin-embedded tissues, including antibodies directed against S-100 protein, CD1a, and fascin.209,211–220 Electron microscopy demonstrates unique pentilaminar inclusions (Birbeck or Langerhans’ granules) within the cytoplasm of Langerhans’ cells (Fig. 21–16).177,209,219

FIGURE 21–9 Pulmonary Langerhans’ cell histiocytosis. (A) Reticular infiltrates with cystic “honeycomb” spaces and relative sparing of the costophrenic angles are seen on this partial view of a conventional posteroanterior (PA) chest radiograph. (B) High-resolution computed tomography (HRCT) scan of Langerhans’ cell histiocytosis showing centrilobular nodules, many with irregular borders and occasional associated cystic spaces.

FIGURE 21–10 CT scan demonstrating late-stage Langerhans’ cell histiocytosis. Cystic spaces predominate, some of which are associated with irregularly shaped nodules.

FIGURE 21–11 Gross features of pulmonary Langerhans’ cell histiocytosis. (A) Cut surface of explanted lung shows extensive scarring and cystic change. Many of the cyst spaces are associated with stellate fibrotic nodules. (B) Cut surface of open lung biopsy showing small gray-white nodules and occasional cysts, the largest situated immediately adjacent to visceral pleura.

Secondary histologic changes are common in LCH and nearly always include pigmented alveolar histiocytes within airspaces immediately adjacent to diagnostic lesions. Pigmented histiocytes reflect the effects of cigarette smoking and are identical to those described in respiratory bronchiolitis and desquamative interstitial pneumonia (DIP), two other forms of smoking-related interstitial lung disease (see Chapter 20). The combination of pigmented alveolar histiocytes and expanded peribronchiolar alveolar septa closely mimics the appearance of DIP and has been referred to as a “DIP-like” reaction.173,193,221 DIP-like changes may be sufficiently prominent to produce patchy ground-glass attenuation on HRCT scan in some patients.193 Indeed, the possibility of underlying LCH should always be considered before making a clinicopathologic diagnosis of DIP. Small foci of intraluminal fibrosis resembling BOOP is another commonly seen secondary finding in LCH, but is rarely a prominent feature.178

Differential Diagnosis

As the lesions of pulmonary LCH become less cellular they become more fibrotic and may be confused with the chronic interstitial pneumonias, especially UIP. It is imperative to distinguish these conditions because of marked differences in prognosis and treatment. At low magnification the first clue to the diagnosis of LCH is the stellate configuration and bronchiolocentric distribution of the interstitial nodules. This contrasts with the diffuse, random, and peripheral subpleural distribution of the interstitial fibrosis in UIP. The presence of pigmented alveolar histiocytes may result in histologic features resembling DIP, the key diagnostic features being the presence of bronchiolocentric nodules in LCH as opposed to the diffuse uniform interstitial pneumonia required for a diagnosis of DIP.

FIGURE 21–12 Low-magnification photomicrographs (original magnification ×40) demonstrating nodules in Langerhans’ cell histiocytosis (LCH). (A) Bronchiolocentric nodule in LCH with small centrally located residual airway lumen surrounded by a dense mixed inflammatory infiltrate. In this example, the lesion lacks the classically stellate configuration except in the upper right-hand corner, where the process trickles into adjacent alveolar septa. (B) Classic nodule more typical of LCH in which a dense interstitial infiltrate extends into peribronchiolar alveolar septa, resulting in characteristic stellate shape.

Eosinophilic pneumonia is predominantly an airspace rather than an interstitial process and is detailed elsewhere in this chapter. Briefly, eosinophilic pneumonia is characterized by a patchy airspace exudate rich in eosinophils and macrophages. An associated interstitial pneumonia is common, but without the bronchiolocentric nodules required for recognition of LCH. Reactive eosinophilic pleuritis is a form of visceral pleural inflammation that occurs after spontaneous pneumothorax of any cause.222 Although this unique form of pleuritis may occur in patients with LCH who experience pneumothorax prior to lung biopsy,178,223 the vast majority of patients with reactive eosinophilic pleuritis have no evidence of underlying LCH.222

FIGURE 21–13 Photomicrograph of Langerhans’ cell histiocytosis in which there are sheets of Langerhans’ cells (left) associated with a minor population of lymphocytes and eosinophils. Contrast the Langerhans’ cell with conventional alveolar histiocytes situated within alveolar spaces on the right. Nuclei of Langerhans’ cells are more highly convoluted and the cytoplasmic borders less distinct.

Pathogenesis

LCH is the consequence of a nonneoplastic accumulation of Langerhans’ cells linked to cigarette smoke. Langerhans’ cells accumulate in respiratory epithelium of distal airways in response to cigarette smoke constituents such as tobacco glycoprotein.175,224–226 Langerhans’ cells within the lesions of LCH show only low levels of proliferation and are instead recruited locally in response to various cytokines including granulocyte-macrophage colony-stimulating factor (GM-CSF).227,228 Recruitment may be facilitated by a switch in expression of certain chemokines (CCR6 and CCR7) important in activation and migration of Langerhans’ cells to target tissues, in this case the lung.229 Tumor necrosis factor-α (TNF-α)–induced synthesis of membrane-associated MMP, particularly MMP-2 and MMP-9, by Langerhans’ cells is an autocrine loop and is another factor important in recruitment and migration of Langerhans’ cells.230–232 Oligoclonal expansion contributes to maintenance of Langerhans’ cell at sites of disease and is accompanied by low levels of genetic instability, but without the features of neoplasia demonstrated in other forms of multifocal or systemic histiocytosis X.233–236 Transforming growth factor-β (TGF-β) derived from respiratory epithelium and alveolar macrophages contributes to accumulation of extracellular matrix components in the fibrotic stage of LCH.237 MMPs and their inhibitors also participate in the pathogenesis of fibrosis and architectural distortion.238 Paracicatricial airspace enlargement is the result of epithelial necrosis, basement membrane damage, and intraluminal fibrosis combined with the effects of elastolytic proteins.239

FIGURE 21–14 Low-magnification photomicrograph (original magnification ×40) demonstrating completely fibrotic bronchiolocentric nodule in Langerhans’ cell histiocytosis. The nodule has a characteristic stellate configuration with associated paracicatricial airspace enlargement (“irregular” or “scar” emphysema), accounting for the prominent cyst change seen on HRCT. At this fibrotic stage, diagnostic Langerhans’ cells are lacking and immunohistochemical stains for Langerhans’ cell–associated antigens such as S-100 protein and CD1a will be negative.

FIGURE 21–15 High-magnification photomicrograph (original magnification ×400) showing cytologic features characteristic of Langerhans’ cells. Nuclei are highly convoluted and folded, resulting in focally prominent nuclear grooves. Chromatin is evenly dispersed, and nucleoli are absent or inconspicuous. Pale-staining cytoplasm is faintly granular with generally indistinct borders. There is a minor associated infiltrate of neutrophils and lymphocytes.

FIGURE 21–16 Ultrastructural features of Langerhans’ cells in Langerhans’ cell histiocytosis. Three Langerhans’ cells with characteristic nuclear features are present in the upper half of the illustration (magnification ×6400). Inset: Characteristic cytoplasmic Langerhans’ cell (Birbeck) granule (magnification ×69,021). (Courtesy of Dr. Samuel Hammar, Bremerton, WA.)

Hypersensitivity Pneumonia (Extrinsic Allergic Alveolitis)

Hypersensitivity pneumonia (-itis), also called extrinsic allergic alveolitis, is a diffuse interstitial lung disorder that results from sensitization to a variety of inhaled organic dusts or aerosols. Offending agents are typically derived from thermophilic bacteria, molds, and various plant or animal proteins. Farmer’s lung was the first described and is perhaps the best-known example of this condition.240 A growing number of similar syndromes have been described and often are named according to the circumstances of exposure (Table 21–2). Other occupational lung diseases, such as asthma, organic dust toxic syndrome, and chronic airway disease (e.g., byssinosis), also result from inhalation of organic dusts and are unrelated to the interstitial disease referred to as hypersensitivity pneumonia.241–246

Criteria for diagnosis of chronic hypersensitivity pneumonia are controversial but generally include an appropriate exposure history, subjective and objective evidence of lung disease temporally linked to antigen exposure, and the presence of serum antibodies directed against the suspected antigen.247–249 Confirming the diagnosis is difficult, in part because the presence of precipitating antibodies reflects exposure and not necessarily disease. For example, precipitating antibodies are present in a sizable minority of exposed farmers and pigeon breeders as well as unexposed office workers and hospitalized patients who lack evidence of respiratory disease.250–259 In addition, antibodies may persist for decades after cessation of exposure.260 False-negative results are common relating to inadequately characterized antigens, methodologic problems with laboratory antigen preparation, and the presence of complex bioaerosols containing multiple antigens.261–263 Use of enzyme-linked immunosorbent assays (ELISA) in populations for which target antigens have been well characterized may increase diagnostic sensitivity.264 Given the absence of a diagnostic “gold standard,” recognition of characteristic histologic findings in lung biopsies often plays a pivotal role in diagnosis.261

Prevalence of hypersensitivity pneumonia is highly variable depending on the specific circumstances of exposure, the diagnostic criteria employed, and the complex interplay of geographic, climatic, and seasonal factors. In farmers and pigeon breeders, for example, prevalence rates hover between 1 and 10%.248 The incidence and prevalence of nearly all forms of hypersensitivity pneumonia is lower in cigarette smokers compared with nonsmokers; smokers account for only 10 to 40% of reported patients in several large series.247,250,263,265–268 Precipitating antibodies against environment antigens are also less frequent in smokers compared with similarly exposed nonsmokers.269,270 These differences likely reflect an inhibitory effect of cigarette smoke on immune regulation in the lung.271

Clinical Features

Hypersensitivity pneumonia is often divided into acute, subacute, and chronic—or more simply acute and chronic—forms. The terms have been inconsistently applied, reflecting significant overlap between these interrelated categories. In general, the term acute hypersensitivity pneumonia is applied to patients suffering from a first attack with symptom duration of less than 1 month. Subacute hypersensitivity pneumonia refers to patients with periodic symptoms for less than 1 year, and chronic hypersensitivity pneumonia refers to patients with progressive respiratory complaints for at least 1 year. Chronic hypersensitivity pneumonia need not be preceded by acute disease, and only a small number of patients with acute disease develop chronic hypersensitivity pneumonia.

Acute hypersensitivity pneumonia follows exposure to relatively large doses of the responsible antigen and is the most easily recognized variant. Symptoms occur within 4 to 6 hours of exposure and include severe dyspnea and cough frequently associated with fever, chills, sweating, nausea, and anorexia.387 Weight loss may occur with frequent or severe attacks.387,388 Conventional chest roentgenograms are abnormal in the majority of patients and show diffuse reticular or nodular opacities.389 HRCT scans are more frequently abnormal and demonstrate patchy areas of ground-glass attenuation, often with a bibasilar distribution and usually associated with small, ill-defined, centrilobular micronodules measuring less than 5 mm in diameter.390–392 Small, ill-defined centrilobular nodules are present in about two thirds of patients and can be helpful in distinguishing hypersensitivity pneumonia from other conditions such as desquamative interstitial pneumonia (see Chapter 20).391 Pulmonary function studies may be normal but in others demonstrate mildly restricted lung volumes with reduced DLCO.393 Symptoms subside 24 to 48 hours after cessation of exposure, and in most patients are followed by radiographic resolution over a period of days or weeks.

Chronic hypersensitivity pneumonia results from intermittent exposure to the offending antigen and in some patients represents the cumulative effect of multiple acute episodes. Indeed, the natural history of chronic hypersensitivity pneumonia is sometimes punctuated by intermittent exacerbations temporally linked to antigen exposure. More commonly patients present with a slowly progressive respiratory syndrome of insidious onset indistinguishable from other diffuse lung diseases, most importantly usual interstitial pneumonia.394 Affected patients may be unaware of the environmental exposure responsible for their respiratory symptoms, further complicating diagnosis. Cough, often with associated dyspnea on exertion, is the most common presenting complaint. Fever usually accompanies respiratory symptoms during periods of acute exacerbation in patients with subacute disease.387,388 Laboratory studies show nonspecific abnormalities, including mild leukocytosis occasionally associated with mild peripheral eosinophilia. Serum levels of angiotensin-converting enzyme are normal, a finding that may have value in those patients for whom sarcoidosis is a competing consideration.395,396 Pulmonary function studies demonstrate restricted lung volumes and reduced DLCO.

Clinical Syndrome (i.e., Circumstances of Exposure) | Antigen Source | Specific Antigen |

|---|---|---|

Bagasse (dried fibrous sugarcane waste) | ||

Bird breeder’s (fancier’s) lung/pigeon breeder’s lung (pet birds including parakeets/budgerigars, exotic birds, pigeons, and doves; droppings from wild geese; handlers exposed to wild birds; feather-filled pillows and duvets) | Avian proteins and bird droppings | |

Cheese worker’s lung | Moldy cheeses | |

Chemical worker’s lung | Isocyanates and trimellitic anhydrides used in manufacturing processes | 1,3-bis (isocyanatomethyl) cyclohexane prepolymer (BIC)284 Diphenylmethane diisocyanate (MDI)285–292 Hexamethylene diisocyanate (HDI)292 Naphthylene-1,5-diisocyanate (NDI)293,294 Toluene diisocyanate (TDI)295,296 Trimellitic anhydride (TMA)297 |

Coffee worker’s lung | Coffee beans | Coffee bean dust extract298 |

Compost/soil/peat moss/greenhouse worker’s lung | Moldy compost/soil/peat moss | Monocillium spp.269 Penicillium citreonigrum269 Streptomyces albus301 |

Esparto fiber disease (esparto leaf harvesting and fiber manufacturing; manufacturing of esparto fiber-containing ropes, rugs, blinds, baskets, bags and sacks, shoes, paper, and mattress covers; plasterers; stucco makers) | Esparto grass (Stipa tenacissiuma and Ligeum spartum) dust and fibers | Aspergillus spp.302,303,305,306 Thermoactinomyces spp., Micropolyspora faeni303 |

Farmer’s lung | Moldy hay and grains | Aspergillus spp.307 Candida albicans308 Sporobolomyces spp.309 Thermoactinomyces spp., |

Fuel chip hypersensitivity pneumonia | Moldy wood fuel chips | Penicillium spp.315 |

Furrier’s lung | Animal hair | Animal (fox, astrakhan) hair316 |

Herb dust hypersensitivity pneumonia | Dried thyme (Thymus vulgaris) | Pantoea agglomerans317 |

Home environment (including Japanese summer-type hypersensitivity pneumonia*318,319) | Airborne fungi; moldy walls and/or floor coverings | *Cryptococcus neoformans320 Pezizia domiciliana320 |

Hot tub lung | Contaminated hot tubs (i.e., spas, Jacuzzis, and whirlpools) | Cladosporium spp.330 |

Humidifier lung: forced air heating and cooling systems | Contaminated forced air heating and cooling systems | Acremonium spp.336 Alternaria tenuis337 Aspergillus spp.337 Aureobasidium pullulans337,338 Thermoactinomyces spp., |

Humidifier lung: ultrasonic humidifiers | Contaminated home ultrasonic humidifiers | Acremonium spp.342 Candida albicans342 Debaryomyces hansenii343 Klebsiella oxytoca344 Rhodotorula spp.345 |

Machine operator’s/metalworker’s hypersensitivity pneumonia | Mycobacterium spp.351 Pseudomonas fluorescens352 | |

Maltworker’s lung | Moldy whiskey maltings | |

Maple bark stripper’s disease | Moldy maple bark | Cryptostroma corticale355 |

Oyster and sea-snail shells | ||

Mushroom worker’s hypersensitivity pneumonia359 | Mushroom spores (shiitake, Lyophyllum aggregatum[Shimeji], Hypsizigus marmoreus [Bunashimeji], Pleurotus ostreatus [oyster mushroom], Pholiota nameko)366–374 | |

Pituitary snuff taker’s disease (nasal insufflation of pituitary snuff for treatment of diabetes insipidus) | Bovine and porcine pituitary snuff | Heterologous (porcine and bovine) and homologous pituitary extracts375 |

Salami worker’s hypersensitivity pneumonia | Fungal inocula used in salami seasoning | Penicillium camembertii376 |

Sauna-taker’s disease | Contaminated water bucket | Pullularia377 |

Suberosis (cork workers) | Moldy cork dust | Unknown378 |

Swimming-pool pneumonitis/“lifeguard lung” | Pool water; airborne and environmental contaminants | Bacterial endotoxin379 Candida albicans380 Thermoactinomyces spp., Micropolyspora faeni381 |

Wood pulp and woodworker’s lung (including sequoiosis) | Wood pulp, moldy wood, moldy sawdust | Alternaria spp.382 Penicillium spp.383 Pine sawdust extract384 Redwood sawdust385 Saccharomonospora viridis386 |

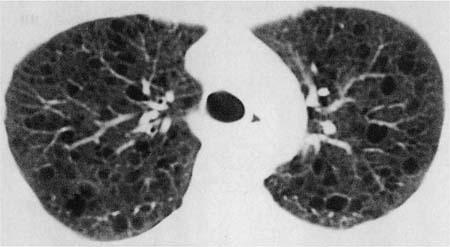

Radiologic findings in chronic hypersensitivity pneumonia are not specific. Conventional radiographs are normal in some patients but in most show a nonspecific pattern of ground-glass and reticular opacities, often with an upper lobe distribution.387,397 Volume loss and honeycomb change are present in patients with longstanding disease. HRCT scans show a distinctive combination of ground-glass opacities, small centrilobular nodules, and mosaic attenuation (Fig. 21–17).392,398–400 Chronic hypersensitivity pneumonia differs from acute disease in that the ground-glass opacities are accompanied by irregular lines and architectural distortion in the form of traction bronchiectasis and bronchiolectasis. Associated honeycomb change is seen in about half of patients, and may be more common in those with pigeon breeder’s lung.392 In patients with honeycomb change, the findings may be indistinguishable from usual interstitial pneumonia.391,392,401 Emphysema has also been described in patients with advanced disease.392

Prognosis for hypersensitivity pneumonia is variable.268 Antigen avoidance is the cornerstone of therapy and is often curative in patients for whom a specific antigen source is identified, assuming the absence of established fibrotic lung disease at the time of diagnosis. Rapid recovery of pulmonary function is typical of acute hypersensitivity pneumonia, although rare fatal episodes have been documented.311 Corticosteroids are useful in accelerating the rate of recovery but do not affect long-term outcome independent of eliminating antigenic exposure.250,393 Lung function improves over a period of months and years, but abnormalities may persist in as many as 20 to 40% of patients.250,255,260,265,267 Disease-specific mortality rates in chronic hypersensitivity pneumonia range from 10 to nearly 30%.255,260,261,263,388 Repeated symptomatic attacks, older age, cigarette smoking, and the presence of established fibrosis and honeycomb change at the time of diagnosis are associated with a more aggressive course.260,261,263,270

FIGURE 21–17 High-resolution CT scan from patient with hypersensitivity pneumonia. Subtle, ill-defined centrilobular nodules are accompanied by ground-glass attenuation.

Pathologic Features

Lung biopsy is rarely necessary for diagnosis and management of patients with acute hypersensitivity pneumonia, and for that reason pathologic findings in this form of the disease are incompletely understood. Rare reports describe a patchy airspace-filling process resembling bronchopneumonia in which both neutrophils and eosinophils are present with an associated necrotizing small vessel vasculitis.311,402 A single report illustrates a bronchiolocentric granulomatous process, but details regarding the circumstances of exposure are lacking.400

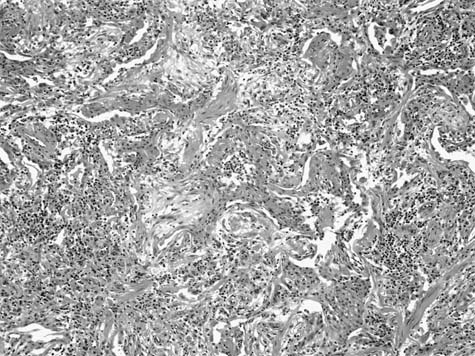

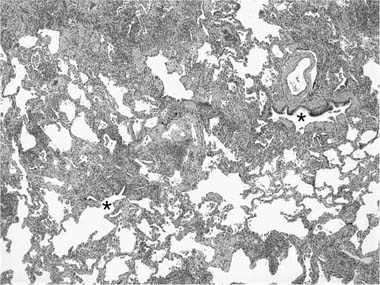

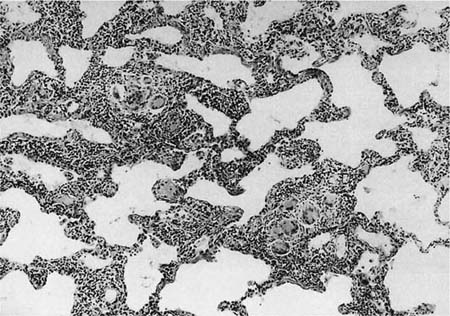

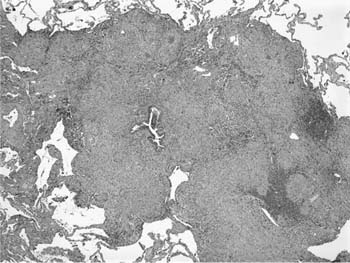

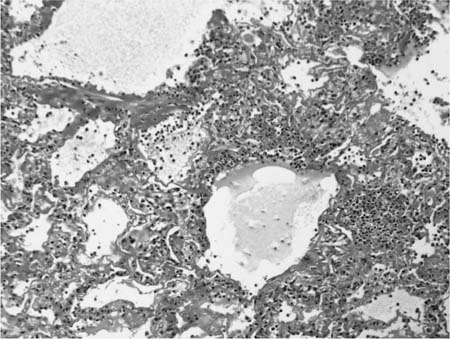

Chronic interstitial pneumonia is the lesion most frequently described in subacute and chronic hypersensitivity pneumonia and is present in nearly all cases.249,388,403–411 At low magnification, alveolar septa are expanded by an infiltrate of mononuclear inflammatory cells accentuated around bronchioles (Fig. 21–18). The inflammatory infiltrate is composed mainly of lymphocytes, plasma cells, and histiocytes, which are occasionally admixed with eosinophils and neutrophils. Epithelioid histiocytes predominate only focally, usually around the airways, and impart a subtle and vaguely granulomatous appearance to the inflammatory infiltrate. Well-formed granulomas are rare. Isolated multinucleated giant cells occur frequently in hypersensitivity pneumonia and in a minority of cases may represent a striking feature (Fig. 21–19). Giant cells often contain various nonspecific cytoplasmic inclusions identical to those seen in sarcoidosis such as Schaumann bodies, asteroid bodies, cholesterol clefts, and birefringent calcium salts. Granulomatous features, although seen in the majority of patients with hypersensitivity pneumonia, may be absent in as many as 30% of surgical lung biopsies.407 In advanced cases the changes are less characteristic and consist mainly of bland interstitial fibrosis and honeycomb change.

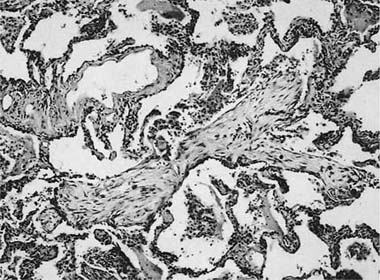

Chronic bronchiolitis is a consistent finding in hypersensitivity pneumonia and is usually present in the form of a cellular peribronchiolar infiltrate, often accompanied by lymphoid aggregates.410,412 The degree of airway inflammation is proportional to the associated interstitial pneumonia.410 Bronchiolitis obliterans is present about half the time and is characterized by polypoid plugs of intraluminal fibroblastic tissue indistinguishable from that described earlier in BOOP (Fig. 21–20).388,404,407,408 Small airway dysfunction results in microscopic foci of obstructive pneumonia characterized by clusters of finely vacuolated, foamy alveolar macrophages within peribronchiolar interstitium and airspaces.

Differential Diagnosis

The differential diagnosis for hypersensitivity pneumonia includes other chronic interstitial pneumonias. Peribronchiolar accentuation of the interstitial inflammatory infiltrate, granulomatous inflammation, and BOOP-like changes are perhaps the most helpful features in distinguishing hypersensitivity pneumonia from the idiopathic interstitial pneumonias (see Chapter 20). Some cases may be indistinguishable from cellular variants of NSIP, indicating that hypersensitivity pneumonia should always be considered a potential etiology in patients with otherwise idiopathic NSIP.261,413 Associated honeycomb change may cause confusion with UIP. The changes in UIP tend to be more peripherally distributed without the bronchiolocentric distribution characteristic of hypersensitivity pneumonia. Peribronchiolar inflammation without fibrosis and isolated multinucleated giant cells are additional features helpful in distinguishing hypersensitivity pneumonia from UIP.

Well-formed granulomas are rare in hypersensitivity pneumonia and if present should raise a suspicion of other entities. Hot tub lung is a syndrome that combines features of hypersensitivity pneumonia and atypical mycobacterial infection resulting from exposure to contaminated hot tubs, spas, Jacuzzis, or whirlpools (see Chapter 8).249,331–335 Lung biopsy findings are similar to those seen in other examples of hypersensitivity pneumonia except that the interstitial pneumonia tends to be less conspicuous and the granulomas are well formed and distributed within airway lumina rather than peribronchiolar interstitium.334 Sarcoidosis differs in that the granulomas are well formed, distributed in a “lymphangitic” pattern, and lack the associated interstitial pneumonia and bronchiolitis typical of hypersensitivity pneumonia. Finally, lymphoid interstitial pneumonia (LIP) is associated with granulomatous inflammation in as many as 40 to 50% of patients and thus can mimic the histology of hypersensitivity pneumonia (see Chapter 19).414,415 Alveolar septa are usually more extensively expanded by lymphocytes, plasma cells, and lymphoid follicles in LIP (see Fig. 19–2 in Chapter 19). Correlation with clinical and radiologic findings may be helpful in difficult cases. Patients with LIP are more likely to have an underlying connective tissue disease or immunodeficiency syndrome, lack an exposure history suggestive of hypersensitivity pneumonia, and have findings on imaging studies that typically differ from those described in patients with hypersensitivity pneumonia.

FIGURE 21–18 Low-magnification photomicrograph (original magnification ×40) showing hypersensitivity pneumonia. There is a variably dense interstitial infiltrate of mononuclear cells, the heaviest infiltrate centered on bronchioles (*, airway lumina).

FIGURE 21–19 Photomicrograph showing poorly formed granulomas in hypersensitivity pneumonia. The granulomas consist mainly of multinucleated giant cells and are set against a backdrop of a cellular interstitial pneumonia.

FIGURE 21–20 Photomicrograph of hypersensitivity pneumonia showing a tuft of organizing connective tissue within an alveolar duct. The changes overlap with those seen in BOOP.

Pathogenesis

Hypersensitivity pneumonia is the consequence of a complex humoral and cellular immune response to an inhaled antigen in vulnerable sensitized patients. Vulnerable patients are likely distinguished by underlying genetic factors not yet well understood, including specific human leukocyte antigen (HLA) class II alleles important in immune response regulation.248,416 Acute hypersensitivity pneumonia represents a type III hypersensitivity reaction linked to immune complex deposition and complement activation.249 Subacute and chronic hypersensitivity pneumonia are more closely affiliated with a cell-mediated type IV reaction in which activated T cells are primary participants. Lymphocytosis in bronchoalveolar lavage (BAL) specimens is characteristic of hypersensitivity pneumonia and can be a useful diagnostic adjunct.417 CD8-positive T cells predominate in acute disease, whereas CD4-positive cells become dominant in longstanding or fibrotic disease.418 BAL lymphocytosis also occurs in asymptomatic individuals who lack other evidence of active disease.251 Other important participants in the inflammatory reaction include mast cells, alveolar histiocytes, and neutrophils.419,420 Macrophage-derived cytokines, including TNF-α and IL-8, further modulate the immune response. Neutrophils may be important in promoting epithelial injury and collagen accumulation in patients with chronic hypersensitivity pneumonia.421

Sarcoidosis

Sarcoidosis is a multisystem disorder of unknown cause with worldwide distribution and protean clinical manifestations. In the United States, African Americans are affected more frequently than whites, and women are affected more often than men.422 The earliest reports published in the 19th century focused on cutaneous manifestations of what would be dubbed sarkoid by Boeck423 in 1899. Sarcoidosis is now known to be capable of involving any organ or tissue. Lung involvement occurs in over 90% of patients and is the dominant feature in most.422,424 Diagnosis usually requires demonstration of a characteristic pattern of granulomatous inflammation in an appropriate clinical and radiologic context.

Clinical Features

Most patients with sarcoidosis present between the ages of 20 and 40 years. Onset before age 10 years or after age 60 is unusual, although 1% of patients are older than 70 at the time of diagnosis. Women tend to be somewhat older than men at the time of diagnosis.422 All but around 10% of patients are symptomatic at presentation. Symptoms are dependent on disease distribution, but respiratory symptoms predominate and usually include a combination of dyspnea and cough. Chest pain and hemoptysis are uncommon but the latter can be massive and life-threatening.425 Nonspecific constitutional symptoms are seen in about a third of patients and include weight loss, low-grade fever, fatigue, and malaise. Cutaneous lesions are the most common extrathoracic manifestation of disease and are present in about 15 to 25% of patients at the time of diagnosis; erythema nodosum and lupus pernio are the most distinctive and correspond to acute and chronic disease, respectively. The combination of erythema nodosum and hilar adenopathy is referred to as Löfgren’s syndrome and is usually a self-limited form of disease.426 Laboratory abnormalities are common and in the majority of patients include elevated serum angiotensin-converting enzyme (ACE), abnormal liver function tests, and polyclonal hypergammaglobulinemia. Antinuclear autoantibodies, hypercalcemia, and hypercalciuria are less common findings, occurring in around 20 to 40% of patients. Pulmonary function tests are abnormal in about two thirds of patients, demonstrating mild restriction, airflow limitation, or a combination of the two. Bronchoscopic biopsy is a sensitive diagnostic tool in patients with lung involvement,427–436 but biopsy of other tissues is useful in those who present with active disease involving extrathoracic sites.

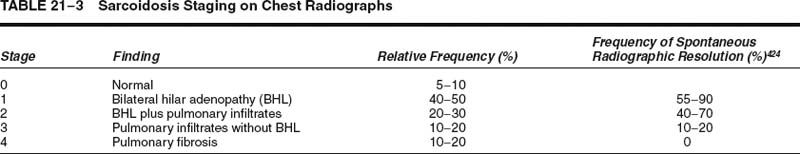

Chest radiographic finding in sarcoidosis are variable. Disease distribution as judged by conventional posteroanterior (PA) chest roentgenograms is the basis for disease staging (Table 21–3).437 A small minority of patients present with normal chest radiographs despite having granulomas on lung biopsies. Hilar lymphadenopathy, with or without associated lung infiltrates, is the most common finding and is seen in as many as 80% of patients. Pulmonary infiltrates may be reticular, reticulonodular, or ground glass in character and often have a predilection for upper lung zones. Fibrotic disease is often associated with bronchiectasis and cystic changes resembling emphysema or honeycomb change.438,439 Pleural effusion is seen in about 10% of patients. CT and HRCT scans typically show irregular linear and nodular opacities distributed along lymphatic routes, particularly bronchovascular bundles, involving mainly upper and middle lung zones (Fig. 21–21).440–443 Irregular morphology of parenchymal opacities coupled with evidence of architectural distortion may occasionally mimic the radiologic appearance of UIP and are associated with chronic disease.439,440,444

Nodular sarcoidosis refers to an uncommon variant characterized by large, well-circumscribed nodules measuring up to 5 cm in diameter.445–447 Nodules are usually multiple and bilateral and mimic the appearance of metastatic disease or other nodular processes such as Wegener’s granulomatosis.447 Central cavitation and ring-shaped opacities have been demonstrated in only a few patients.448,449 Isolated solitary pulmonary nodules are rare.450,451

The natural history of sarcoidosis is variable and dependent on several factors including race, sex, age, and respiratory symptoms at diagnosis.422,424,452 Spontaneous remissions occur within 2 years of diagnosis in a large majority of patients.424,453 Chronic progressive disease develops in 10 to 30% of patients. Sarcoidosis-associated mortality is variable and is as high as 5% in referral populations.454 Mortality rates of less than 1% have been observed in population-based studies and may more closely approximate the natural history of disease.454,455 Black race, pulmonary hypertension, and use of supplemental oxygen are associated with shorter survival in patients with fibrotic lung disease.456,457 Lung and cardiac involvement are the two most common causes of death in autopsied sarcoidosis patients.458 Systemic corticosteroids are the standard of care for patients requiring treatment and are generally reserved for progressive disease with functional deterioration, especially when it involves the lungs, heart, central nervous system (CNS), or eye.424,459 Cytotoxic agents are used in selected patients.424,460,461 Novel therapies (e.g., pentoxifylline, thalidomide, and infliximab) that target TNF-α, an important participant in the pathogenesis of fibrosis, show mixed success as potential therapeutic alternatives.460–464 Lung transplantation has been employed in some patients, but sarcoidosis recurs in lung allografts with greater frequency than other forms of interstitial lung disease.465–468

FIGURE 21–21 High-resolution CT scan in sarcoidosis. Nodular densities distributed along septa and bronchovascular bundles are more prominent near the hilum but do extend to the pleura, especially along the major fissure. [From Swensen S, Aughenbaugh G, Brown L, Harms G. High-resolution computed tomography of the lung and bronchial tree. In: Taveras J, Ferrucci J, eds, Radiology: Diagnosis-Imaging-Intervention, vol 1. Philadelphia: JB Lippincott, 1991:1–12, with permission of the publisher.]

Pathologic Features

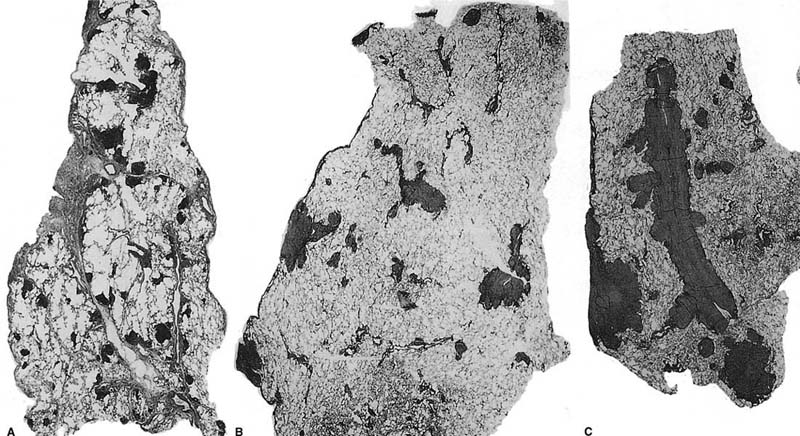

Gross findings in classical pulmonary sarcoidosis comprise variably sized nodules with a distinctive predilection for bronchovascular bundles, interlobular septa, and visceral pleura (Fig. 21–22). In minimally affected cases, the gross appearance may be nearly normal or show only tiny white nodules corresponding to granulomas. In other cases, confluent and coalescent granulomas with associated fibrosis form macroscopic nodules measuring up to several centimeters in maximum dimension.

Discrete, well-formed, nonnecrotizing granulomas are the histologic hallmark of sarcoidosis (Fig. 21–23).469–471 The granulomas are often associated with a peripheral infiltrate of lymphocytes and a distinctive pattern of lamellar fibrosis. Granulomas comprise a compact circumscribed aggregate of epithelioid and multinucleated histiocytes with minimal or no central necrosis. Giant cells in sarcoidosis frequently contain various nonspecific cytoplasmic inclusions such as asteroid bodies, basophilic Schaumann’s bodies, and birefringent crystalline particles corresponding to calcium oxalates and other calcium salts.472,473 In some cases birefringent particles may be sufficiently prominent to raise concerns for occupational lung disease (Fig. 21–24). Aside from mild inflammation and variable degrees of fibrosis in the immediate vicinity of the granulomas in sarcoidosis, the remainder of the lung tissue is relatively unaffected without significant associated interstitial pneumonia.

FIGURE 21–22 Sarcoidosis. Gross appearance of the lung shows a delicate lacework of granulomas that follows lymphatic routes in the pleura and septa and along veins and bronchovascular rays. (Courtesy of Dr. Bensch, Stanford, CA.)

Distribution of the granulomas in a lymphangitic pattern is a distinctive feature of sarcoidosis that can be extremely helpful in diagnosis. Granulomas are situated within the interstitium rather than the airspaces and involve predominantly bronchovascular bundles and interlobular septa (Figs. 21–25 and 21–26). Airway involvement is nearly universal and is occasionally associated with bronchial stenosis and airflow limitation.474–476 Pleural involvement is somewhat less conspicuous but, in rare cases, is a dominant site of disease.477–482 Nonnecrotizing granulomatous “vasculitis” is common in surgical lung biopsies and is consistent with involvement of bronchovascular bundles and interlobular septa (Fig. 21–27).483–485 Vascular involvement only rarely results in pulmonary hypertension that mimics pulmonary veno-occlusive disease.486–489 Pulmonary hypertension in patients with sarcoidosis is more commonly a consequence of fibrosis and end-stage cystic change.

FIGURE 21–23 Photomicrograph (original magnification ×200) showing well-formed granuloma in patient with sarcoidosis. Epithelioid histiocytes are organized in a compact granuloma with only occasional multinucleated giant cells. The granuloma is associated with a minor peripheral infiltrate of lymphocytes and early lamellar fibrosis in the upper right corner. There is no central necrosis, although minimal fibrinoid necrosis is occasionally seen.

Granulomas occasionally coalesce and combine with hyalinizing fibrosis to form macroscopic nodules, corresponding to nodular sarcoidosis described earlier as a radiologic variant (Fig. 21–28). Over time fibrosis may obliterate the underlying granulomatous process and partially obscure the diagnostic features. Transformation of granulomas into broad zones of hyalinized sclerosis and scar also occurs in lymph nodes.

Differential Diagnosis

The main differential diagnosis in sarcoidosis is granulomatous infection. In addition, superimposed granulomatous infection can occur in patients with underlying sarcoidosis.490–493 Special stains and cultures should be performed in all cases of suspected sarcoidosis to more confidently exclude infection. Extensive necrosis and intraluminal location of granulomas are features more typical of infection than sarcoidosis. Hypersensitivity pneumonia (see later) differs from sarcoidosis in that the granulomas are much less well formed, frequently consisting of only isolated multinucleated giant cells, and almost invariably associated with a cellular interstitial pneumonia in which lymphocytes predominate. The poorly formed granulomas of hypersensitivity pneumonia are also distinctly bronchiolocentric in distribution without the more widespread lymphangitic distribution characteristic of sarcoidosis. Berylliosis is associated with histologic findings indistinguishable from those described for sarcoidosis, the distinction depending on correlation with clinical and laboratory data.470,494,495

FIGURE 21–24 High-magnification photomicrograph (original magnification ×400) showing large number of cytoplasmic inclusions in sarcoidosis. Many of the inclusions are transparent but birefringent when viewed with polarized light and represent calcium oxalates. Partially calcified lamellated concretions (Schaumann’s bodies) are also present.

FIGURE 21–25 Whole mount sections of open lung biopsy specimens showing various degrees of granulomatous involvement of the lung in sarcoidosis. (A) The dark nodules represent early granulomas surrounded by chronic inflammatory cells distributed along septa, vessels, and pleura. (B) Early coalescence of granulomas is seen to form small nodules around bronchovascular structures and in the pleura. (C) There is more extensive consolidation and coalescence of granulomas in the pleura and along a vessel cut longitudinally.

FIGURE 21–26 Low-magnification photomicrograph (original magnification ×40) showing confluent granulomas in sarcoidosis. Peribronchiolar interstitium is expanded and distorted by well-formed granulomas with a minor associated infiltrate of lymphocytes.

FIGURE 21–27 Vascular involvement in sarcoidosis. (A) A small muscular pulmonary artery shows epithelioid and multinucleated histiocytes expanding the vessel wall. (B) An elastic tissue stain highlights similar involvement in a pulmonary vein.

FIGURE 21–28 Nodular sarcoidosis. (A) Whole mount section showing a large nodular lesion that was radiographically visible. The central portion of the nodule (left center) is hyalinized and acellular. (B) Low-magnification photomicrograph (original magnification ×20) demonstrating a centrally fibrotic nodule (upper left) in which fibrosis partially obscures the granulomatous nature of the process. Scattered granulomas are present at the periphery of the nodule.

Necrotizing sarcoid granulomatosis (NSG) was first proposed as a unique entity by Liebow496 in 1973. NSG overlaps clinically and histologically with nodular sarcoidosis. Indeed, most authorities consider NSG a subset of nodular sarcoidosis distinguished by broad zones of infarct-like parenchymal necrosis.497,498 The combination of well-formed confluent granulomas coalescing to form nodules, infarct-like parenchymal necrosis, and granulomatous vasculitis are the histologic hallmarks of NSG.499 Granulomatous infection is a more important differential diagnosis than nodular sarcoidosis in such cases and should be vigorously excluded using a combination of special stains and cultures.

Pathogenesis

Sarcoidosis is the result of an abnormal immune response in which activated macrophages and CD4-positive T cells react to an as yet undiscovered environmental antigen in genetically susceptible hosts.424 Several environmental candidates have been proposed, including several infectious pathogens. The use of various molecular techniques has suggested a potential role for Mycobacterium tuberculosis, Propionibacterium, and other bacterial organisms, but the results are mixed and must be interpreted with caution.500–506 There is no conclusive evidence that sarcoidosis is caused by an infectious agent, although certain microbes may serve as antigenic triggers in at least a subset of patients.507,508

Sarcoidosis is propagated by activated macrophages and T lymphocytes whose effects are mediated through various cytokines.424,507,509 CD4-positive helper cells predominate at sites of active disease. Lymphocyte-derived IL-2, IL-12, interferon-γ, and IL-18 are important in recruiting and maintaining local populations of immune effector cells with concomitant granuloma formation.424,507,509 Macrophage-derived cytokines and chemokines (e.g., IL-1, IL-6, IL-8, IL-15, interferon-γ, GM-CSF, TNF-α, TGF-β, and PDGF) further contribute to granuloma formation, fibroblast recruitment and activation, and extra-cellular matrix deposition.424,463,464,510–517

Lymphangioleiomyomatosis and Tuberous Sclerosis

Pulmonary lymphangioleiomyomatosis (LAM), also called lymphangiomyomatosis, is a rare condition that affects young women almost exclusively. LAM occasionally involves extrapulmonary tissues (“lymphangioleiomyomas”), most commonly mediastinal and retroperitoneal lymph nodes.518,519 Lung disease indistinguishable from sporadically occurring LAM occurs in 1 to 3% of patients with tuberous sclerosis complex (TSC), a multisystem autosomal-dominant disorder characterized by seizures, mental retardation, autism, and hamartomatous tumors in various organs (e.g., cutaneous angiofibroma, CNS subependymal giant cell astrocytoma, cardiac rhabdomyoma, and renal angiomyolipoma).520

Clinical Features

Sporadic LAM occurs in women with an average age at presentation in the fourth decade of life. Postmenopausal women are occasionally affected.521,522 Breathlessness and pneumothorax are the most common presenting manifestations of lung disease (Table 21–4).523–529 Cough and hemoptysis are uncommon as presenting symptoms, occurring in 19% and 9% of patients, respectively.523–529 Nearly all patients experience shortness of breath during the course of their illness. Pneumothoraces eventually occur in two thirds of patients and commonly recur. Pulmonary function testing typically demonstrates normal lung volumes with airflow obstruction, disproportionately reduced DLco, and hypoxemia.

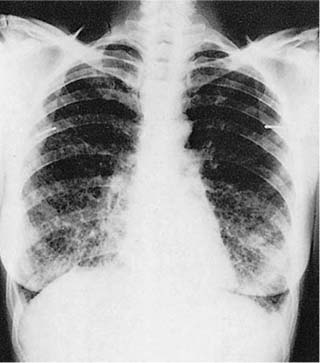

Chest radiographs are normal early in the course of the illness, but eventually show diffuse interstitial opacities, cystic spaces resembling honeycomb change, and paradoxical lung enlargement (Fig. 21–29). HRCT scans are more sensitive than conventional roentgenograms in detecting abnormalities in LAM and show sharply demarcated, rounded, thin-walled cysts uniformly distributed in the lungs (Fig. 21–30).530–535 This characteristic radiologic appearance allows accurate diagnosis in a high percentage of cases, although distinction from other cystic lung diseases including emphysema and LCH can be difficult.536–538 Abdominal CT scans are frequently abnormal, demonstrating renal angiomyolipomas in 50 to 60% of patients.525,539–541 Involvement of mediastinal, retroperitoneal, and mesenteric lymph nodes, usually in the form of one to three discrete masses, is observed in some patients.518 Nearly all patients with extrapulmonary LAM also have pulmonary disease, but diagnosis of extrapulmonary lesions may precede recognition of lung involvement by months or years.519

Symptom | Prevalence at Presentation (%) | Prevalence During the Course of Disease (%) |

|---|---|---|

Dyspnea | 42 | 88 |

Pneumothorax | 50 | 66 |

Cough | 19 | 46 |

Chylothorax | 8 | 30 |

Hemoptysis | 9 | 25 |

FIGURE 21–29 Lymphangioleiomyomatosis. Typical chest radiograph showing diffuse bilateral reticular infiltrates with roughly normal lung volumes.

Patients with underlying TSC tend to be women of reproductive age without CNS disease and thus resemble patients with otherwise sporadic LAM.520 Reports suggest that the prevalence of LAM in women with TSC is higher than that reported in historical studies, affecting 30 to 40% of women with TSC.542–544 LAM rarely occurs in men with TSC.545,546 Respiratory involvement contributes disproportionately to morbidity and mortality and was the third most common cause of death in a review of 40 patients who died of TSC-related complications.547

The natural history of LAM is difficult to predict. A progressive course culminating in respiratory failure and death occurs in some patients.524,527 Recent studies indicate that the prognosis may be better than that suggested in historical reports, with 10-year disease-specific survivals of 70 to 80%.528,529,548 Extent of disease on CT scan and rate of decline in lung function are helpful in predicting disease progression.527,549 Progestogen or antiestrogen therapy is commonly used to treat LAM;525,528,550–553 other hormonal manipulations have been attempted with varying degrees of success.529,554 Transplantation is another therapeutic alternative, but is occasionally complicated by recurrent disease in lung allografts.529,555–560

FIGURE 21–30 Computed tomography scan of the chest in lymphangioleiomyomatosis. Discrete well-demarcated cysts are randomly distributed throughout the lung fields without associated nodules.

Pathologic Features

The most consistent gross finding in lung specimens with LAM is the presence of cystic spaces diffusely involving pulmonary parenchyma (Fig. 21–31). Localized disease with gross and histologic characteristics of LAM is extraordinarily rare and has been described in association with a clear cell (“sugar”) tumor in only a single patient.561 In early diffuse disease the cysts are discrete and separated by normal-appearing lung tissue. Advanced disease is characterized by confluent cystic spaces resembling emphysema or diffuse honeycomb change. Hemosiderin deposition results in brown discoloration of the lung parenchyma in later disease stages.

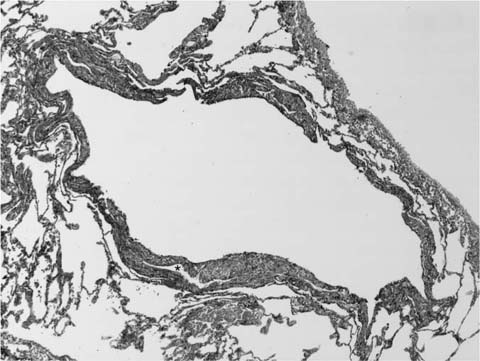

The presence of modified smooth muscle cells is the histologic hallmark of LAM.523,524,527,548 Cytologically distinct muscle cells are distributed along lymphatic pathways, focally expanding bronchovascular bundles and surrounding arteries, veins, and lymphatic channels (Fig. 21–32). Associated hyperplasia of alveolar pneumocytes is common.562 LAM smooth muscle cells tend to be spindled in shape, although plump epithelioid forms also occur and predominate in some cases. The cytologic characteristics differ from normal smooth muscle in that LAM cells are more plump with larger rounded nuclei, small but sometimes conspicuous eosinophilic nucleoli, and pale-staining cytoplasm characterized by a slightly granular and finely vacuolated texture (Fig. 21–33). Spindled and epithelioid cells coalesce focally to form microscopic nodules that are often situated around or immediately adjacent to bronchioles.523,563 Cystic “emphysematous” spaces are common and are a helpful clue to the diagnosis at low magnification (Fig. 21–34). Cystic spaces are centered on airways and contain bundles of specialized smooth muscles cells within at least a portion of their walls. Hemosiderin is frequently present within surrounding airspaces and is a striking feature in some cases (Fig. 21–35).

Semiquantitative assessment of histologic stage may provide prognostically useful information. The degree of cystic change and the extent of tissue infiltration by lesional smooth muscle cells in surgical lung biopsies correlates with other measures of disease severity.527,548 Matsui and colleagues548 demonstrated 100% 10-year survival in patients whose biopsies showed involvement of less than 25% of the sampled lung tissue compared with 52% 10-year survival in patients whose biopsies showed cysts or smooth muscles cells in over 50% of the biopsy surface area.

Extrapulmonary LAM usually involves intrathoracic, retroperitoneal, or intraabdominal lymph nodes.519 Involved nodes present as single or more commonly multiple well-circumscribed nodules averaging around 5 cm in greatest dimension. Masses as large as 20 cm have been reported. Spindle and epithelioid smooth muscles cells identical to those described in pulmonary lesions are arranged in ill-defined fascicles that surround and infiltrate lymph node sinuses and occasionally extend into perinodal soft tissues (Fig. 21–36). As in pulmonary LAM, mitotic figures are rare and there is no associated necrosis.

FIGURE 21–31 Gross appearance of lymphangioleiomyomatosis in surgical lung biopsy (A) and explanted lung (B). (A) Cut surface of wedge lung biopsy shows discrete cystic spaces separated by normal lung. Some of the cysts are immediately adjacent to the visceral pleura and account for the high risk of pneumothorax in these patients. (B) Cut surface of explanted lung showing extensive cystic change in patient with advanced lymphangioleiomyomatosis.

FIGURE 21–32 Photomicrograph (original magnification ×100) showing proliferation of smooth muscle cells in lymphangioleiomyomatosis. Predominantly spindle cells are distributed around vascular spaces immediately adjacent to a respiratory bronchiole (*).

FIGURE 21–33 High-magnification photomicrographs (original magnification ×400) showing spindled (A) and epithelioid (B) cells in lymphangioleiomyomatosis. Nuclei are more rounded than those seen in normal smooth cells, and nucleoli are more easily identified. The cytoplasm is pale staining and has a granular and finely vacuolated quality.

The modified smooth muscle cells of LAM are thought to be derived from perivascular epithelioid cells.564 Expression of melanogenesis-associated proteins, most commonly HMB45, is the most distinctive immunohistochemical feature of the specialized smooth muscle cells in both pulmonary and extrapulmonary LAM.519,525,564–570 Melanoma antigen recognized by T cells (MART-1) is a less sensitive marker for this condition.566 HMB45 is a useful diagnostic marker in difficult cases, including small transbronchial biopsies, although HMB45-staining is frequently focal and therefore subject to sampling bias.525,565,571 Confocal microscopy and ultrastructural studies identify immunophenotypically distinct small spindle and larger epithelioid cells and suggest that HMB45 staining is confined to epithelioid cells.570,572 LAM smooth muscle cells are also immunoreactive with antibodies directed against muscle-associated proteins (e.g., actin and desmin) and frequently stain for estrogen and progesterone receptor proteins.568,569,571–573 The unique staining characteristics of LAM are also typical of renal angiomyolipoma, a neoplasm derived from perivascular epithelioid cells and associated with TSC.564,568 Clear cell (“sugar”) tumors are also immunoreactive for HMB45 and have been occasionally described in association with LAM.561,574

FIGURE 21–34 Low-magnification photomicrograph (original magnification ×40) showing cystic space in lymphangioleiomyomatosis. This example is situated immediately adjacent to visceral pleura and shows an irregularly thickened wall due to the presence of a population of spindled smooth muscle cells. Focally the spindle cells surround the lumen of a vascular space (*).

Micronodular pneumocyte hyperplasia (MNPH) is an unusual epithelial proliferation that occurs in a subset of patients with sporadic LAM or TSC.545,574–579 MNPH comprises circumscribed proliferations of cytologically bland type 2 pneumocytes in a pattern resembling bronchioloalveolar adenocarcinoma (Fig. 21–37). Muir and colleagues578 reported a series of 14 patients with MNPH, including nearly all previously reported examples. Ten (71.4%) patients, all women, had associated LAM and seven of them had other manifestations of TSC. MNPH in association with LAM has also been described in a man with underlying TSC.545 Indeed, the combination of LAM and MNPH in a lung biopsy is strong evidence in support of a diagnosis of TSC in a patient of either gender. Intrapulmonary clear cell (“sugar”) tumor and intrapulmonary angiomyolipoma combined with MNPH are other rare manifestations of lung involvement in TSC.574,579

FIGURE 21–35 Photomicrograph (original magnification ×100) showing hemosiderin deposition in lymphangioleiomyomatosis. A portion of a cyst wall in which there is subtle smooth muscle proliferation (arrows) is associated with deposition of coarse, refractile hemosiderin granules within the cytoplasm of alveolar histiocytes. In some cases the extent of hemosiderin deposition may raise concern for the possibility of a hemorrhage syndrome.

FIGURE 21–36 Lymph node involvement in lymphangioleiomyomatosis. Only rare islands of lymphocytes (arrowheads) remain among the massive proliferation of smooth muscle bundles that replace most of the lymph node.

Differential Diagnosis