INDICATIONS/CONTRAINDICATIONS

The primary indication for the repair of a paraesophageal hernia is a symptomatic hernia. The most common symptoms are postprandial pain (59%), vomiting (31%), and dysphagia (30%), but may include postprandial dyspnea, acid reflux, iron deficiency anemia, or symptoms of volvulus, acute incarceration or ischemia with severe retrosternal chest pain mimicking myocardial ischemia.1 Repair of asymptomatic paraesophageal hernia may be considered in patients who are fit for surgery, given that these hernias enlarge over time, often becoming symptomatic, although catastrophic complications, such as gastric strangulation, are rare occurring in only about 3%.1–3 A transthoracic approach may be used for repair of any paraesophageal hernia but is particularly appropriate for Type III or IV hernias and should be considered for reoperative repairs, obese patients, and those with acquired esophageal shortening. A transthoracic approach facilitates the assessment of acquired esophageal shortening, which may be difficult to appreciate through a transabdominal approach.

Contraindications for transthoracic repair include impaired cardiopulmonary reserve or the inability to tolerate single-lung anesthesia. Previous left-sided thoracotomy or pulmonary sepsis, wherein one may anticipate difficulty in exposure of the hernia due to extensive adhesions, may be taken into consideration.

PREOPERATIVE PLANNING

PREOPERATIVE PLANNING

Preoperative assessment should include an assessment of the foregut anatomy, noting particularly the location of the gastroesophageal junction, with barium swallow and upper endoscopy. Prolonged exposure to acid reflux may lead to transmural inflammation and acquired esophageal shortening. In such cases, an esophageal-lengthening procedure is required for a successful durable repair. Factors that may be predictive of acquired esophageal shortening include an incarcerated hiatus hernia, a large hiatus hernia (greater than 5 cm), Type III hernia, peptic stricture, and Barrett’s esophagus.4,5 Assessment of esophageal length is ultimately determined at the time of repair after mobilization of the esophagus, but preoperative endoscopy, barium swallow, and the distance between upper cervical and lower esophageal sphincters on esophageal manometry provide useful insights that may advise intraoperative decision making.

Esophageal manometry should be included in the preoperative assessment if one is considering performing a total or 360-degree fundoplication. This assessment is less critical if one is planning a partial fundoplication. A 24-hour pH study is not required but may be included in the preoperative assessment if the primary indication for repair is acid reflux.

Other important components of the preoperative assessment include assessment of cardiopulmonary reserve. The patient must have adequate pulmonary reserve to tolerate single-lung anesthesia and maintain postoperative pulmonary toilet. Active esophagitis should be treated with proton-pump inhibitors before proceeding with repair. Further, any active pulmonary infection, for example, secondary to aspiration, should also be treated prior to surgery. Active smokers should avoid smoking for a minimum of 2 weeks prior to surgery.

SURGERY

SURGERY

The principles of repair are as follows:

Tension-free reduction of the hernia contents back into the abdomen

Tension-free reduction of the hernia contents back into the abdomen

Removal of the hernia sac from the chest

Removal of the hernia sac from the chest

Closure of the defect by tension-free closure of the crura

Closure of the defect by tension-free closure of the crura

Anchor the stomach in abdomen through performance of fundoplication and crural pexing sutures

Anchor the stomach in abdomen through performance of fundoplication and crural pexing sutures

The steps include the following:

1. Mobilization of the esophagus

2. Protection of the vagus nerves

3. Mobilization and resection of the hernia sac

4. Assessment of esophageal length and Collis gastroplasty, if required

5. Fundoplication

6. Crural closure

Anesthetic Considerations

Single-lung anesthesia is required using either a double-lumen endotracheal tube or bronchial blocker. A thoracic epidural may be beneficial for postoperative pain control; alternatively, a paravertebral catheter or intercostal nerve blocks may be placed at the time of thoracotomy.

Positioning

The patient should be positioned in full right lateral decubitus position with an axillary role in place and all pressure points well padded. The operative table may be slightly flexed or “broken” at its midpoint to open up the intercostal spaces.

Incision

A posterolateral thoracotomy incision is performed preserving the serratus anterior muscle, entering the chest through the sixth intercostal space. The dome of the diaphragm will interfere with the exposure of the hiatus if the seventh intercostal space is used. Some surgeons resect a segment of the sixth rib to facilitate exposure.

Technique

After entering the chest, the left lung is deflated by the anesthesiologist, and the inferior pulmonary ligament is divided using an electrocautery. Using a malleable retractor and one or more sponges, the lung may be packed out of the way superiorly and anteriorly.

The mediastinal pleura is then opened over the esophagus just anterior to the descending aorta beginning at approximately the level of the inferior pulmonary vein or higher, if necessary, to get above the hernia and at a level where the vagus nerves are still identifiable adherent to the esophagus. Dissection may be accomplished using scissors, electrocautery, or ultrasonic device. The esophagus is mobilized and encircled with a Penrose drain or umbilical tape taking care to keep both vagus nerves with the esophagus. The esophagus is mobilized proximally as far as the aortic arch if necessary and distally to the hiatus. When mobilizing distally, the middle esophageal artery will be divided. This artery must be controlled or troublesome bleeding will result. Traction on the Penrose drain will facilitate both proximal and distal dissection of the intrathoracic esophagus.

The esophagus and hernia sac are mobilized from the mediastinum and pericardium and from the right chest and the contralateral pleura. Ideally, one should avoid entering the contralateral pleural space to avoid unrecognized accumulation of blood into the dependent hemithorax. This dissection may be completed using both sharp dissection and gentle blunt dissection with a pledget or a sponge stick. When mobilizing the esophagus and hernia sac away from the pericardium, care must be taken to avoid excessive pressure on the heart to prevent hypotension or arrhythmia. Gentle traction on the pericardium with an Allison lung retractor or sponge stick will facilitate this dissection. Grasping the pericardium risks injury to the underlying heart and may cause pericardial irritation leading to pericardial effusion or even cardiac tamponade and should be undertaken with great care. The hernia sac is mobilized circumferentially down to the diaphragmatic hiatus. This dissection can be quite challenging when addressing very large paraesophageal hernias.

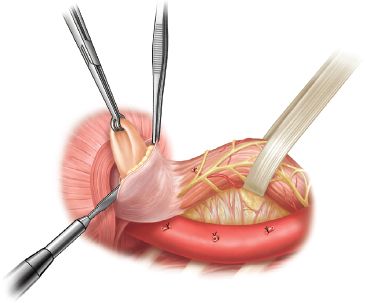

Once the hernia is completely mobilized, the sac is opened anteriorly (Fig. 12.1). The hernia “sac” (which is actually the attenuated and greatly expanded transversalis fascia draped over the herniated intrathoracic abdominal viscera) is divided circumferentially at the level of the hiatus from the short gastric vessels posteriorly around to the pericardium anteriorly and then continuing posteriorly until joining the original plane of dissection. As stated earlier, care must be taken to avoid injury to the vagus nerves, particularly during this critical phase of the operation where orientation of the transposed abdominal viscera and the esophagus can be challenging. Once this dissection of the hernia sac is complete, the margins of the hiatus, the right and left crura, and the caudate lobe of the liver can be visualized. The cardia of the stomach will have then been completely mobilized.

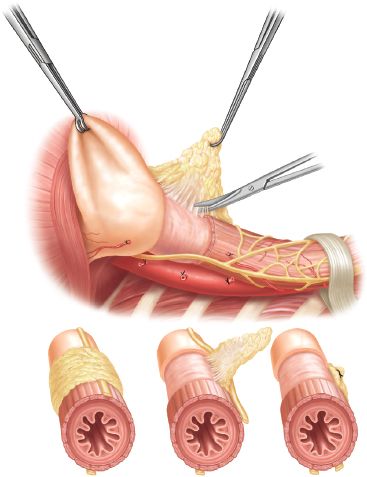

The “sac” is then dissected off the stomach. When resecting the sac off the gastroesophageal junction, care should be taken to identify and preserve both vagus nerves. After removing the anterior component of the sac, the stomach and esophagus are retracted anteriorly, and the posterior component of the sac is identified and removed. This dissection can be quite tedious as the sac is very thickened and vascular. Meticulous hemostasis is required to prevent excessive intraoperative blood loss. Once the sac has been removed, the gastroesophageal fat pad is removed, beginning anterior to the right vagus and continuing across to the left, mobilizing the left vagus off of the stomach to clearly identify the gastroesophageal junction (Fig. 12.2).

Figure 12.1 After mobilizing the esophagus above the hernia, the esophagus is encircled with a Penrose drain including both vagus nerves within the Penrose. The hernia sac has been mobilized circumferentially away from the mediastinal structures and the diaphragmatic hiatus. The sac is incised anteriorly. This opens the sac into the peritoneal cavity. The sac is then incised circumferentially so that the proximal stomach and gastroesophageal junction are freely mobile. The sac is then dissected off the stomach and esophagus.

Figure 12.2 The gastroesophageal fat pad is then dissected and removed, beginning just in front of the right vagus nerve. The dissection is carried over to the left, exposing the gastroesophageal junction, using the ultrasonic device. In completing this, both vagus nerves are mobilized laterally so that they lay behind the esophagus.