Figure 7.1 Original Collis illustrations from 1957. (From: Collis JL. An operation for hiatus hernia with short esophagus. Thorax. 1957;12(3):181–188, with permission).

INDICATIONS/CONTRAINDICATIONS

INDICATIONS/CONTRAINDICATIONS

The absolute indication for performing a Collis gastroplasty is the presence of obvious esophageal shortening that prohibits reduction of the gastroesophageal junction into the abdomen without tension. This esophageal shortening is usually the result of transmural fibrosis and esophageal stricture related to chronic GERD injury. It is appreciated that at least 2 to 3 cm of distal esophagus within the abdominal cavity below the repair of a hiatal hernia is required to re-establish the normal intra-abdominal esophageal length estimated by radiographic studies and esophageal manometric analysis of normal subjects. Of course, this restoration of normal intra-abdominal length must be accomplished without tension to avoid recurrence of the hiatal hernia. The diaphragm contracts 30,000 times each day for respiration and the esophagus contracts 1,000 times a day for swallowing. Therefore, tension on the repair can lead to wrap herniation or disruption over time, and more importantly, any retching or sudden increase in intra-abdominal pressure can also increase the likelihood of hiatal hernia recurrence.

Standard antireflux procedures in cases of shortened esophagus are unlikely to achieve a sufficient tension-free length of intra-abdominal esophagus and consequently the likelihood of hiatal hernia recurrence, as with any other hernia, is increased.7,8 The primary issue is defining the true short esophagus. While some authors recommend the use of a Collis gastroplasty in all cases of reflux stricture due to the inherent tendency for esophageal shortening (Fig. 7.2),9,10 others have shown that good results can be obtained with dilation and standard antireflux procedures if the above criteria of 2 to 3 cm of tension-free intra-abdominal esophagus can be achieved.14–16 As described by Collis and others,6,17 many patients have only moderate esophageal shortening that can be treated by an extended mediastinal dissection and esophageal mobilization. O’Rourke et al. defined an esophageal mediastinal dissection less than 5 cm as type I and an esophageal mediastinal dissection greater than or equal to 5 cm as type II. While such nomenclature might help analyze surgical decision making and guide this discussion, such terminology has not been commonly adopted and is rarely reported in typical operative notes. On average, a type II dissection was carried up between 7 and 10 cm into the mediastinum. In cases reported by O’Rourke in which type II dissection failed to release an adequate segment of tension-free intra-abdominal esophagus, a Collis gastroplasty was recommended.17

Figure 7.2 Hiatal hernia with stricture and shortened esophagus. Morse C, Pennathur A, and Luketich JD. Laparoscopic techniques in reoperation for failed antireflux repairs. In: Pearson FG, Patterson GA, eds. Pearson’s thoracic & esophageal surgery. 3rd ed. Philadelphia: Churchill Livingstone/Elsevier; 2008: 367–375 (Used with permission).

Relative indications for performing a Collis gastroplasty include situations associated with increased risk of recurrence following antireflux surgery, for example, a large hiatal hernia, a failed prior antireflux procedure, or morbid obesity, which is associated with increased intra-abdominal pressure after hiatal hernia repair.18–20 Collis gastroplasty should be avoided in patients with severe inflammatory conditions of the stomach that increase the risk of staple-line failure and leak.

PREOPERATIVE PLANNING

PREOPERATIVE PLANNING

Preoperative assessment of esophageal shortening can be challenging. Conditions in which esophageal shortening is likely to occur include fibrotic strictures, ulceration with dense periesophageal fibrosis, large or fixed hiatal hernias with dense adhesions around the sac and following failed prior antireflux procedures, particularly where there is proximal migration of the gastroesophageal junction into the chest. The presence of a large paraesophageal hiatal hernia is also considered by some to be highly predictive of the presence of short esophagus.20–22 Urbach et al. reported a 4.5-fold increased use of gastroplasty in their experience when the surgery was performed for paraesophageal hernia, 4.3-fold increase in the setting of Barrett’s esophagus, and 11.6-fold likelihood of gastroplasty during “redo” surgery.20 Of course, this is not necessarily the experience of other skilled esophageal surgeons. However, Urbach’s work does give us some direction as to which patients may have anatomic changes suggestive of esophageal shortening where gastroplasty may be considered. It is also important to realize that no preoperative assessment can provide information about the degree of elasticity or fibrosis of the esophagus. Therefore, the decision to perform a gastroplasty is an intraoperative decision based on all the factors mentioned above and ultimately, the intraoperative estimate of an adequate length of intra-abdominal distal esophagus for tension-free hiatal hernia repair and fundoplication.23

The preoperative modalities available to assess the likelihood that esophageal shortening will require a Collis gastroplasty include barium contrast studies, endoscopy, manometry, and cross-sectional radiographic imaging. The following findings have been associated with the presence of short esophagus.

Larger (>5 cm) nonreducing hiatal hernia indicates long-standing disease with associated mediastinal scarring and shortened esophagus. This can be assessed on contrast swallow or cross-sectional radiographic imaging.

Larger (>5 cm) nonreducing hiatal hernia indicates long-standing disease with associated mediastinal scarring and shortened esophagus. This can be assessed on contrast swallow or cross-sectional radiographic imaging.

Esophageal stricture that suggests transmural inflammation and mediastinal scarring. Strictures can be diagnosed on contrast swallow as well as upper endoscopy.

Esophageal stricture that suggests transmural inflammation and mediastinal scarring. Strictures can be diagnosed on contrast swallow as well as upper endoscopy.

Barrett’s esophagus is most commonly associated with a hiatal hernia and is a marker of long-standing GERD. Although this is not an independent factor associated with esophageal shortening, the presence of Barrett’s esophagus is commonly seen in the large hiatal hernia (>5 cm length) and peptic stricture setting.

Barrett’s esophagus is most commonly associated with a hiatal hernia and is a marker of long-standing GERD. Although this is not an independent factor associated with esophageal shortening, the presence of Barrett’s esophagus is commonly seen in the large hiatal hernia (>5 cm length) and peptic stricture setting.

Lower esophageal sphincter (LES) at 35 cm or less from the incisors as assessed using upper endoscopy or manometry in an adult male of average height. The normal esophageal (LES) location is around 40 cm from the upper incisors.

Lower esophageal sphincter (LES) at 35 cm or less from the incisors as assessed using upper endoscopy or manometry in an adult male of average height. The normal esophageal (LES) location is around 40 cm from the upper incisors.

The LES is normally seen within the positive pressure swings with respiration seen with an intra-abdominal location of the LES. If the LES is noted in a negative pressure swing environment of the thoracic cavity on manometric evaluation, this suggests that the LES is in a shortened circumstance. Of course, these manometric findings must be correlated with barium esophagram and endoscopic findings suggestive of hiatal hernia.

The LES is normally seen within the positive pressure swings with respiration seen with an intra-abdominal location of the LES. If the LES is noted in a negative pressure swing environment of the thoracic cavity on manometric evaluation, this suggests that the LES is in a shortened circumstance. Of course, these manometric findings must be correlated with barium esophagram and endoscopic findings suggestive of hiatal hernia.

SURGERY

SURGERY

Transabdominal Collis Gastroplasty

Collis gastroplasty is performed as one component of the primary procedure used to correct a hiatal hernia and control of gastroesophageal reflux. Occasionally, an open gastroplasty via an abdominal approach is required. This is relatively rare and is done when the primary esophageal procedure is being approached through laparotomy, for example, in patients who have had multiple prior laparotomies, multiple prior antireflux procedures, or who are undergoing another unrelated open abdominal procedure.

Intraoperative endoscopy following esophageal mobilization is strongly advised for the assessment of shortened esophagus.5,24 After completing the hiatal and mediastinal dissections, we routinely perform endoscopy to assess adequate intra-abdominal length of the esophagus. The gastric folds provide a good anatomic landmark of the GE junction as they are normally located at or a few millimeters below the Z-line.24 After the endoscope is passed into the gastric fundus, the point of passage between the tubular esophagus and the stomach is recognized by means of transillumination or by palpating the tip of the scope. The distance between the hiatus and GE junction is estimated. A stitch is placed on the GE junction to mark it and to facilitate subsequent Collis gastroplasty and antireflux wrap calibrations.

If a diagnosis of shortened esophagus is made after adequate transhiatal mediastinal mobilization, we will make the decision to perform the Collis gastroplasty. The orogastric tube is removed, and a 48- to 52-French bougie is advanced down the esophagus into the stomach carefully with manual assistance by the surgeon. We always perform the gastroplasty after placing a bougie to avoid esophageal narrowing. Open gastroplasty can be performed using the technique of EEA circular stapler or wedge gastroplasty, although we prefer to use wedge gastroplasty due to the complications associated with the EEA technique.

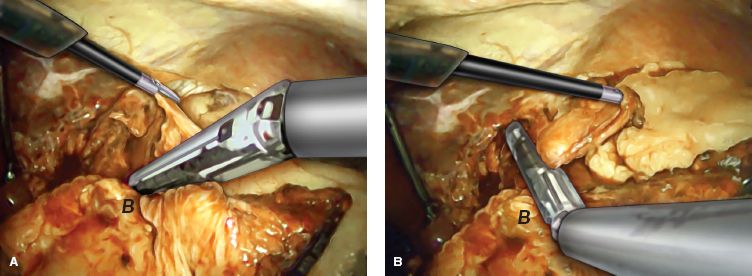

To accomplish the wedge gastroplasty, an angulating linear stapler with a thick tissue load is introduced. The assistant retracts the fundus of the stomach inferiorly and slightly to the patient’s left, thereby pulling the lesser curve against the bougie. The stapler is directed perpendicular to the long axis of the planned neoesophageal segment, aiming the tip of the stapler to the planned distal end of the gastroplasty (Fig. 7.3). The assistant retracting the stomach should manipulate the top edge of the greater curve into the stapler jaw, and then retract the stomach inferiorly thereby withdrawing as much of the greater curve out of the stapler to avoid excessive resection of the fundus. It is important that the greater curvature be the portion of the stomach most deeply into the jaws of the stapler. It is easy to create an oblique bite of the stomach if careful attention is not paid to this point. The tip of the stapler is carefully advanced to fit snugly against the intraluminal bougie and fired to create a transverse stapled resection line. It is important that the bougie is reached with the final firing, and this is assured when the dilator is pushed away when closing the stapler. The second staple line is completed longitudinally with the stapler aimed toward the mediastinum while applied firmly against the bougie. It is crucial that the assistant place gentle lateral traction on the wedge of stomach to be removed during the second staple-line firing. The stapler is fired once or twice to produce a stapled wedge of stomach. The two stapled resection lines result in a small triangular wedge resection of the stomach at the angle of His, effectively lengthening the intra-abdominal esophagus by length of the upward directed staple line. Since the neoesophagus is aperistaltic, it is advisable to limit this length as much as possible. The bougie is then removed and an orogastric tube can be passed back so that the tip is in the proximal stomach.

Figure 7.3 Wedge Gastroplasty A: Surgeon’s left hand lifts the gastric cardia with a grasper and the assistant grasps the greater curvature and gives a downward and lateral traction. A linear stapler is placed so that it approximates the bougie in the esophagus. B: After the initial firing of the stapler, the wedge gastroplasty is completed by one or two additional firings parallel to the bougie. B indicates location of the bougie in the esophagus. (A laparoscopic Collis gastroplasty is depicted; the same principles apply when performing open transabdominal Collis gastroplasty).