1

CHAPTER

![]()

Normal Lung, Common Artifacts, and Incidental Findings

This chapter briefly reviews architectural landmarks in the lung that are important for understanding pathologic alterations and explains how they are used in formulating diagnoses. Commonly encountered artifacts and incidental lesions that may cause confusion in histologic interpretation are reviewed. Suggestions for the optimal handling of tissue specimens are also provided.

TOPICS

Normal Lung Architecture

Normal Lung Architecture

Handling of Tissue Specimens

Handling of Tissue Specimens

Approach to Diagnosis

Approach to Diagnosis

Artifacts

Artifacts

Artifactual Collapse

Artifactual Collapse

Fresh Hemorrhage

Fresh Hemorrhage

Bubble Artifact

Bubble Artifact

Incidental Findings

Incidental Findings

Corpora Amylacea

Corpora Amylacea

Interstitial Megakaryocytes

Interstitial Megakaryocytes

Bone Marrow Emboli

Bone Marrow Emboli

Blue Bodies

Blue Bodies

Cytoplasmic (Mallory) Hyaline

Cytoplasmic (Mallory) Hyaline

Minute Meningothelial-Like Nodules (MLNs)

Minute Meningothelial-Like Nodules (MLNs)

Entrapped Pleural Fragments

Entrapped Pleural Fragments

Nodular Histiocytic/Mesothelial Hyperplasia

Nodular Histiocytic/Mesothelial Hyperplasia

NORMAL LUNG ARCHITECTURE

Detailed reviews of the microscopic anatomy of the lung can be found in other textbooks, but a few basic landmarks are important to remember when evaluating biopsy or surgical specimens:

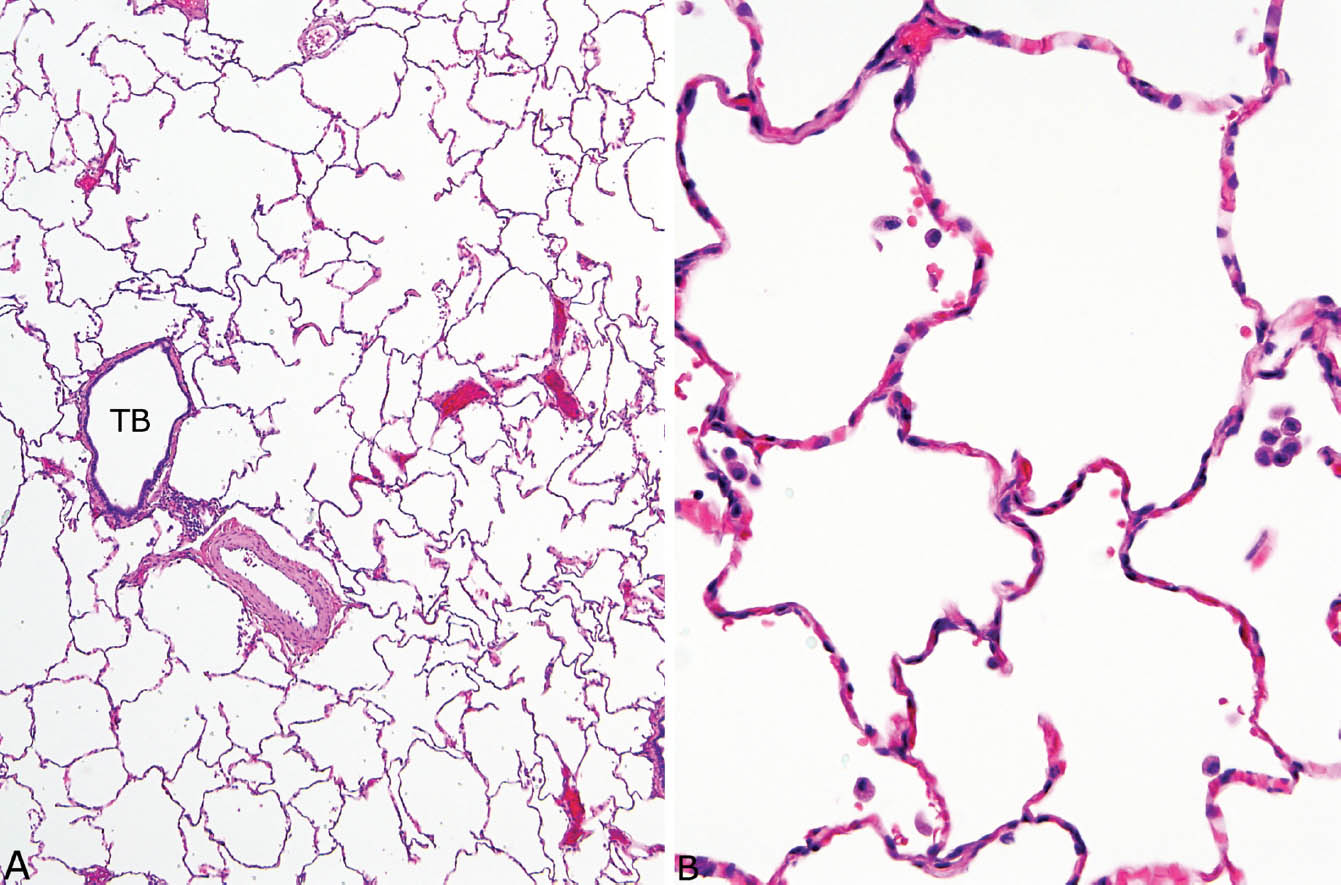

Pulmonary arteries and bronchioles course together, and are similar in size (Figure 1.1). This relationship helps one to confirm that a particular blood vessel is an artery, and it also confirms bronchiolocentricity of an inflammatory process if the affected bronchiole is destroyed (see Figures 6.23 and 6.24).

Pulmonary arteries and bronchioles course together, and are similar in size (Figure 1.1). This relationship helps one to confirm that a particular blood vessel is an artery, and it also confirms bronchiolocentricity of an inflammatory process if the affected bronchiole is destroyed (see Figures 6.23 and 6.24).

Terminal (membranous) bronchioles contain a full lining of ciliated respiratory tract epithelium and have a continuous smooth muscle layer in their walls (Figure 1.1).

Terminal (membranous) bronchioles contain a full lining of ciliated respiratory tract epithelium and have a continuous smooth muscle layer in their walls (Figure 1.1).

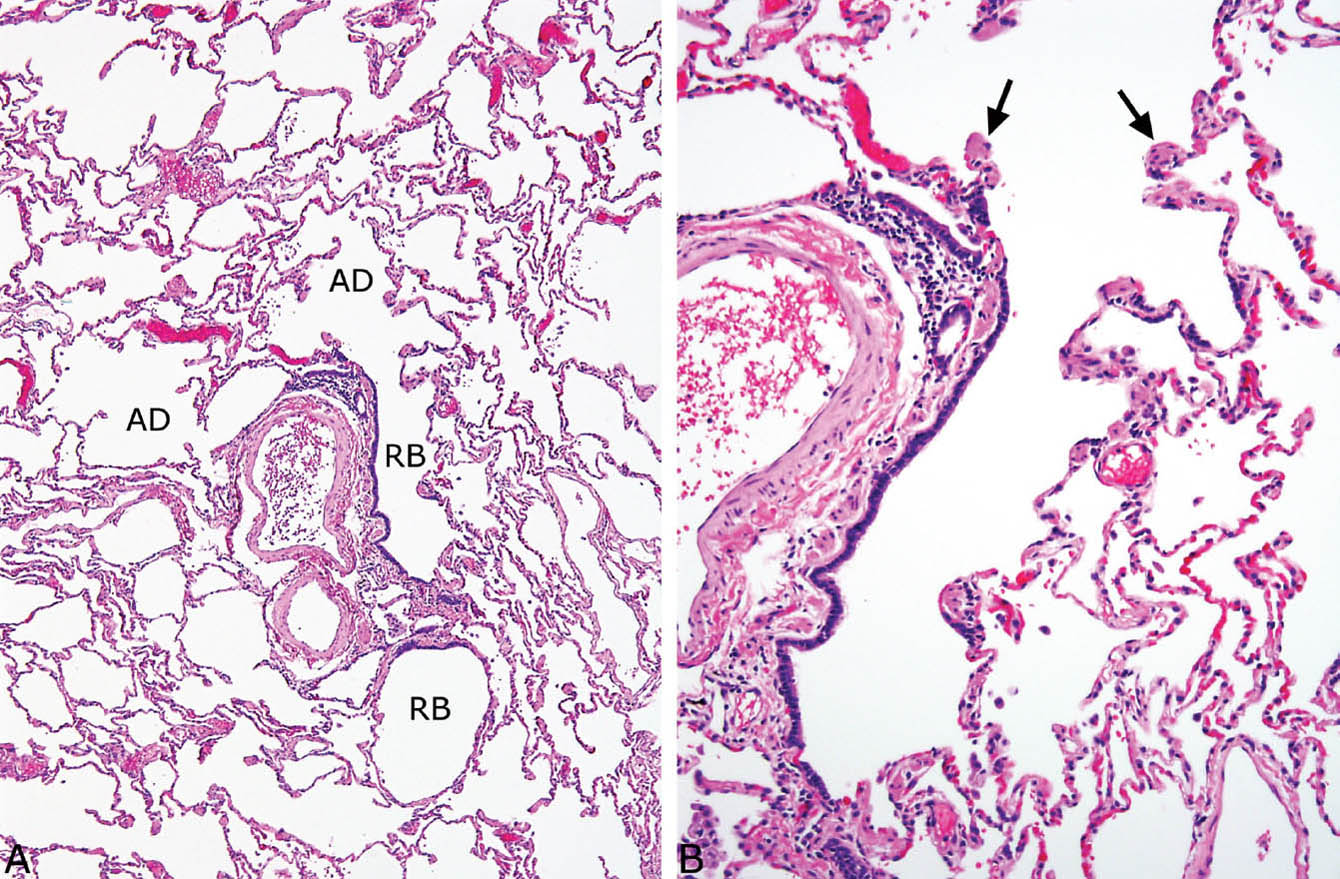

Respiratory bronchioles are partially lined by ciliated respiratory tract epithelium and open up into alveolar ducts (Figure 1.2).

Respiratory bronchioles are partially lined by ciliated respiratory tract epithelium and open up into alveolar ducts (Figure 1.2).

Small collections of chronic inflammation, bronchial-associated lymphoid tissue (BALT), are common in the walls of bronchioles and by themselves are not a significant abnormality.

Small collections of chronic inflammation, bronchial-associated lymphoid tissue (BALT), are common in the walls of bronchioles and by themselves are not a significant abnormality.

Smooth muscle bundles protrude along the interstitium at the mouth of alveolar ducts and are present along the wall of alveolar ducts (Figure 1.2B). They may appear hyperplastic in emphysema.

Smooth muscle bundles protrude along the interstitium at the mouth of alveolar ducts and are present along the wall of alveolar ducts (Figure 1.2B). They may appear hyperplastic in emphysema.

Alveolar septa are thin, membranous structures within which only scattered nuclei, mostly from endothelial cells, can be seen (Figure 1.1B). Alveolar lining cells are generally not visible in normal lung, and when prominent are indicative of prior injury or interstitial lung disease.

Alveolar septa are thin, membranous structures within which only scattered nuclei, mostly from endothelial cells, can be seen (Figure 1.1B). Alveolar lining cells are generally not visible in normal lung, and when prominent are indicative of prior injury or interstitial lung disease.

FIGURE 1.1 Normal lung. (A) At low magnification, a terminal bronchiole (TB) is seen adjacent to a pulmonary artery. Note that the artery and the bronchiole are similar in size. The surrounding alveoli are normal. (B) Higher magnification of the alveolated parenchyma shows thin, membranous, alveolar septa containing only scattered nuclei mainly from capillary endothelium. Distinct alveolar lining cells are not visible. A few macrophages are scattered within the airspaces.

FIGURE 1.2 Normal lung. (A) A respiratory bronchiole (RB) is seen adjacent to a pulmonary artery in this field, and it opens into alveolar ducts (AD). (B) Higher magnification view of the RB shows its discontinuous smooth muscle layer, as well as the smooth muscle bundles (arrows) that are present at the mouth of the adjacent AD.

Alveolar spaces may contain scattered alveolar macrophages, but numerous macrophages within contiguous alveoli are abnormal.

Alveolar spaces may contain scattered alveolar macrophages, but numerous macrophages within contiguous alveoli are abnormal.

Pulmonary veins course separately from arteries and are located within interlobular septa (see Figures 10.19 and 10.20).

Pulmonary veins course separately from arteries and are located within interlobular septa (see Figures 10.19 and 10.20).

Interlobular septa are connective tissue structures that extend from the visceral pleura into portions of underlying lung, and they contain lymphatic spaces in addition to veins.

Interlobular septa are connective tissue structures that extend from the visceral pleura into portions of underlying lung, and they contain lymphatic spaces in addition to veins.

Pulmonary lymphatic spaces are located within the bronchovascular bundles, interlobular septa, and the pleura. They are normally inconspicuous, but they may be artifactually dilated in specimens that have been fixed by inflation.

Pulmonary lymphatic spaces are located within the bronchovascular bundles, interlobular septa, and the pleura. They are normally inconspicuous, but they may be artifactually dilated in specimens that have been fixed by inflation.

HANDLING OF TISSUE SPECIMENS

Although some pathologists advocate inflating surgical biopsy specimens with formalin using a syringe and needle, we have never found this technique to be necessary. In fact, inflation has its own hazards, including overinflation of airspaces, dilution of airspace exudates, and dilatation of lymphatic spaces, and we do not recommend it. Rather, the most important step in handling these specimens is immersing them immediately after excision in formalin, because leaving them exposed to air promotes atelectasis. A second important step is to use a fresh, sharp blade and to section with a gentle sawing motion, being careful not to compress the specimen during cutting or with one’s fingers. All staples should be removed before sectioning and the sections made perpendicular to the pleura starting at the (soft) excision margin and extending to the (firmer) pleural surface.

For transbronchial biopsy specimens, as with surgical biopsies, the most important step is to put the tissue into formalin immediately, because the main cause of atelectasis in these specimens is exposure to air. It is frustrating to receive relatively large tissue fragments that are uninterpretable because of atelectasis, and the clinicians should be advised about correcting this problem.

Gentle sectioning with sharp knives should also be used on lobectomy or pneumonectomy specimens. These specimens may be inflated first with formalin through the bronchi and fixed for 1 to 2 hours before sectioning. Inflation is not necessary, however, but it can facilitate dissection and help one to precisely localize lesions to determine their relationship with bronchi and other structures.

Helpful Tip—Handling of Tissue Specimens

Careful handling of the fresh tissue is the most important step in ensuring optimal microscopic interpretation: Do not allow the specimen to air dry, and do not unduly compress during sectioning.

Careful handling of the fresh tissue is the most important step in ensuring optimal microscopic interpretation: Do not allow the specimen to air dry, and do not unduly compress during sectioning.

APPROACH TO DIAGNOSIS

Histologic Examination

The lung can be considered broadly to consist of two main compartments: interstitium and airspace. The interstitium is the supporting structure of the lung and includes alveolar septa, tissue surrounding bronchovascular bundles, and interlobular septa. The airspaces include the lumens of bronchi and alveolar spaces and all structures in between. An important first step in examining lung for non-neoplastic disease is to assess which compartment is primarily involved by the disease process. Many diseases affect the interstitium or airspaces predominantly and are reviewed in Chapters 2, 3, and 4, whereas others may affect both compartments relatively equally (diffuse alveolar damage, Chapter 5). Not all conditions can be categorized in this way, however, as some destroy lung in a cross-country fashion, replacing normal architecture altogether (nodular infiltrates and necrotizing processes, Chapters 6, 7, 8, and 12), while others involve blood vessels or bronchioles primarily (Chapters 10 and 11) and largely spare the adjacent parenchyma. Of course, not every disease fits nicely into these patterns, but systematic examination of the specimen with regard to the predominant site of involvement is a good starting point in the evaluation. Determining the distribution of the process, whether mainly peribronchiolar, perivascular, lymphangitic, or random, provides additional important information for synthesizing a diagnosis.

Rarely, biopsies appear superficially normal; yet patients are said to have severe respiratory compromise. Although such specimens may have not adequately sampled an abnormal area, subtle vascular (pulmonary hypertension, Chapter 10) or bronchiolar (constrictive bronchiolitis obliterans, Chapter 11) changes should be suspected and carefully excluded.

A number of common special stains are routinely used in evaluating lung biopsy or excision specimens. Organism stains are used when indicated by the histologic findings or a history of immunocompromise, and we recommend Ziehl–Neelsen or auramine–rhodamine stain for acid-fast bacilli, and Gomori methenamine silver (GMS) stain for fungi. Elastic tissue stains can be helpful in evaluating blood vessels. Some pathologists advocate connective tissue stains, especially Trichrome, to evaluate fibrosis in interstitial lung disease. We have not found this stain to be either necessary or useful. In fact, we would advise against its use in small transbronchial biopsy specimens because it obscures underlying cellular details and wastes tissue that could have been used for additional H and E or other more helpful stains.

Clinical Input

A clinical history is always helpful in interpreting lung biopsies, but it does not have to be detailed, and is not necessary in all cases. Knowing the basic presenting manifestations, whether acute or chronic, the patient’s immune status, whether immunocompromised or immunocompetent, and whether the radiographic findings are localized or diffuse is sufficient in most cases. A more detailed clinical history with radiographic description can be elicited if needed in more difficult cases.

The clinical history should be viewed as a useful ancillary finding that not only helps the pathologist formulate a diagnosis, but, more importantly, may prevent him or her from making erroneous diagnoses. It is best, however, that pathologists examine the slides initially before the clinical situation is known and formulate a differential diagnosis based on the morphologic features alone. The clinical history then can be used to refine the pathologic differential diagnosis. Reviewing the clinical history before examining the microscopic slides is not recommended, however, as it steers the pathologist toward the clinical impression and it may prevent an unbiased evaluation of the pathologic findings.

Radiographic Findings

As mentioned earlier, superficial knowledge of the basic radiographic findings, whether localized or diffuse, is usually sufficient to interpret most lung biopsies. However, it helps pathologists to understand the radiology jargon to some extent, especially as additional, more detailed radiographic descriptions can contribute to diagnosis in pathologically difficult cases. Some common radiology terms and their significance are listed in Table 1.1.

Helpful Tips—Approach to Diagnosis

Examine the microscopic slides first and formulate a differential diagnosis based on pathologic findings before reviewing clinical information.

Examine the microscopic slides first and formulate a differential diagnosis based on pathologic findings before reviewing clinical information.

Determine the predominant site of involvement, whether interstitial, airspace, or crosscountry, but remember that diseases are only rarely strictly confined to a single compartment, and judgment is required to determine the predominant one.

Determine the predominant site of involvement, whether interstitial, airspace, or crosscountry, but remember that diseases are only rarely strictly confined to a single compartment, and judgment is required to determine the predominant one.

Consider pulmonary hypertension or constrictive bronchiolitis obliterans when biopsies from patients with severe respiratory compromise appear otherwise normal.

Consider pulmonary hypertension or constrictive bronchiolitis obliterans when biopsies from patients with severe respiratory compromise appear otherwise normal.

Use clinical information to confirm the pathologic impression or to prevent an erroneous diagnosis, but do not be biased by the clinical history before looking at the slides.

Use clinical information to confirm the pathologic impression or to prevent an erroneous diagnosis, but do not be biased by the clinical history before looking at the slides.

TABLE 1.1 Common Radiology Terms and Correlation With Pathology Findings

Radiology Term | Chest CT Appearance | Pathology Correlates |

Air bronchogram | Air-filled bronchus visible within consolidated lung | Occurs in airspace filling process |

Consolidation | Dense opacification, often with air bronchograms, all other lung landmarks obscured, usually localized | Acute pneumonia, organizing pneumonia, other airspace filling processes |

Crazy paving | Thickened interlobular and intralobular lines within ground glass opacity, usually diffuse or multifocal | Classically in alveolar proteinosis, also in other diseases |

Ground glass opacity (GGO) | Incomplete, hazy opacification in which bronchial and vascular structures are visible, localized or diffuse | Active inflammatory process, either interstitial or airspace or both |

Honeycomb change | Small uniform spaces with well-defined walls, often at lung periphery, associated with reticular opacities | Corresponds to gross honeycombing, characteristic of usual interstitial pneumonia |

Mosaic attenuation | Patchwork of regions of differing attenuation | Air trapping, as in small airways disease, or patchy interstitial disease |

Reticular/reticulonodular infiltrates | Thin linear densities, sometimes with tiny nodules, usually diffuse | Interstitial diseases with fibrosis |

Traction bronchiectasis | Dilated bronchi within fibrotic lung and honeycomb change | Associated with parenchymal scarring and honeycomb change |

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree