Nonseminomatous Malignant Germ Cell Tumors of the Mediastinum

John D. Hainsworth

F. Anthony Greco

Mediastinal germ cell tumors are neoplasms that occur almost exclusively in men <35 years of age. Although rare, these tumors are of special interest because they are potentially curable with optimal therapy. There are several histologic subtypes. With the exception of pure seminomas, these tumors are grouped together as nonseminomatous germ cell tumors. Because the management of these histologic subtypes is identical in most instances, they are considered together in this chapter.

Etiology and Pathogenesis

Mediastinal nonseminomatous germ cell tumors were first described by Kantrowitz.34 The first speculation concerning the oncogenesis of extragonadal malignant germ cell tumors was by Schlumberger,58 who postulated that these neoplasms arise from primitive rests of totipotential cells that become detached from the blastula or morula during embryogenesis. Subsequently, Fine and associates16 proposed that extragonadal malignant germ cell tumors arise from primitive germ cells in the endoderm of the yolk sac or from the urogenital ridge, which fail to completely migrate into the scrotum during development. At present, both hypotheses remain unproven, and the oncogenesis of extragonadal and malignant germ cell tumors remains uncertain. Although either hypothesis can explain the occurrence of extragonadal malignant germ cell neoplasms in the retroperitoneum or mediastinum, the occasional occurrence of these tumors in other locations, such as in the pineal or sacrococcygeal areas, is best explained by Schlumberger’s hypothesis.

Although the concept of an extragonadal site of origin of these neoplasms is generally accepted, a few reports have raised the possibility that some of them are actually metastatic lesions from an occult primary tumor in the gonad. Patients with small testicular primaries, carcinoma in situ, or fibrous scars in the testicle, thought to represent sites of regressed primary tumors, have been reported by Meares and Briggs45 as well as by Azzopardi,1 Rather,55 and Daugaard10 and their associates. However, these findings have been rare in large autopsy series such as those reported by Oberman and Libcke52 and Cox8 as well as by Johnson33 and Luna42 and their associates. In addition, large numbers of patients with malignant mediastinal germ cell tumors have had long-term survival after either mediastinal irradiation for pure seminoma or combination chemotherapy for nonseminomatous tumors. In these patients, testicular recurrences have not been a clinical problem. Primary malignant mediastinal germ cell tumors therefore should be accepted as a distinct clinical entity. The coexistence of an occult testicular primary is rare and should not influence the treatment of these patients.

Although the cause of malignant mediastinal germ cell neoplasms is unknown, men with Klinefelter’s syndrome have a peculiar propensity to develop these tumors. Klinefelter’s syndrome is a relatively common chromosomal abnormality characterized by hypogonadism, azoospermia, and elevated gonadotropin levels in association with an extra X chromosome. Richenstein56 first reported the occurrence of an extragonadal germ cell tumor in a patient with Klinefelter’s syndrome. Since that time, this association has been confirmed by multiple investigators, including Sogge,60 Curry,9 McNeil,44 Turner,63 and Lachman38 and their associates. Four of 22 consecutive patients (18%) treated by Nichols and associates50 for mediastinal nonseminomatous germ cell tumors had karyotypic confirmation of Klinefelter’s syndrome. For unexplained reasons, the average age of patients with Klinefelter’s syndrome who develop extra- gonadal germ cell tumors is approximately 10 years younger than that of those developing this tumor in the absence of Klinefelter’s syndrome. Testicular germ cell neoplasms have rarely been reported in association with Klinefelter’s syndrome; therefore the association with malignant mediastinal germ cell neoplasms seems specific. Recently, an increased incidence of several other cancers in men with Klinefelter’s syndrome has been recognized by Swerdlow and associates.61

The explanation for this association is unknown, but it is reasonable to assume that the chromosomal abnormality plays some role. Increasing evidence indicates that underlying germ cell defects are common in men who develop germ cell tumors. Clinical history of infertility is common, and Carroll and colleagues4 have described abnormal testicular biopsy findings, including decreased spermatogenesis, interstitial edema, and peritubular fibrosis. In addition, Hartmann and associates27 have recognized an increased incidence of testicular germ cell tumors in patients who have been successfully treated for extragonadal germ cell tumor. These data suggest that either a congenital or an acquired germ cell defect contributes not only to defective

spermatogenesis but also to the development of extragonadal germ cell tumors.

spermatogenesis but also to the development of extragonadal germ cell tumors.

Incidence

Malignant germ cell tumors of the mediastinum are uncommon and have accounted for approximately 1% to 5% of all germ cell neoplasms in series reported by Collins and Pugh7 and by Einhorn and Williams.13 They have accounted for 3% to 10% of tumors originating in the mediastinum in early reported series. However, it is probable that true incidence of mediastinal germ cell tumors was underestimated in these early series, since several other poorly differentiated malignancies arising in the mediastinum (thymoma, lymphoma) are difficult to distinguish by histologic examination. More recently, Motzer and colleagues47 detected the i(12p) chromosomal abnormality in 12 of 40 young males who had “poorly differentiated carcinoma” in the mediastinum. This chromosomal marker was first identified by Bosl and associates2 and is specific for germ cell tumors. Excellent treatment results using chemotherapy for germ cell tumors in men with poorly differentiated carcinoma involving the mediastinum has been reported by Greco23 and Fox18 and their associates.

Malignant mediastinal germ cell tumors occur almost exclusively in men; in a review of 184 such tumors by Moran and Suster,47 all 184 tumors occurred in men. In spite of the small number of cases reported in women, the histology spectrum and biology of malignant mediastinal germ cell tumors seem similar in women and men.

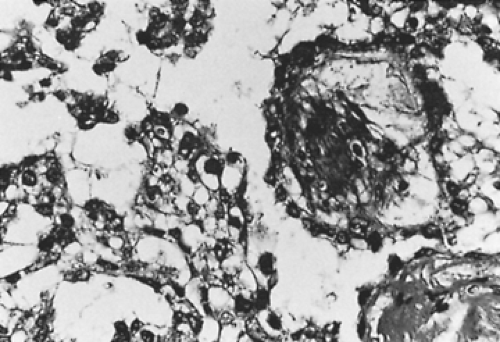

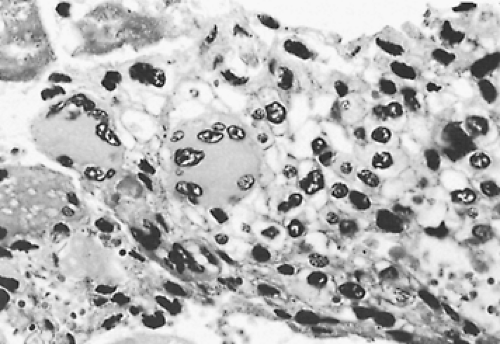

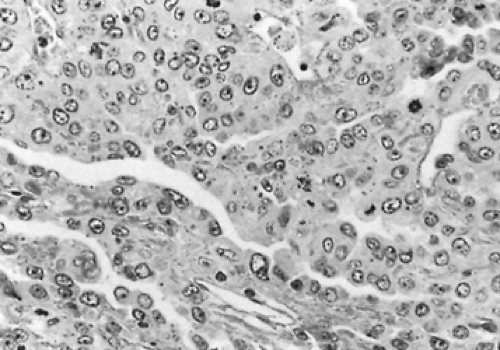

Approximately 50% of mediastinal germ cell tumors have nonseminomatous histologies, while 50% are pure seminomas. The incidence of the various nonseminomatous histologies has varied in published series, most of which have contained fewer than 30 patients. In a large, retrospective series composed of 229 cases seen at the Armed Forces Institute of Pathology and Mount Sinai Medical Center in Miami, Moran and Suster46 reported the following incidences of nonseminomatous histologies: teratocarcinoma, 41%; endodermal sinus (yolk sac) tumor, 35% (Fig. 194-1); choriocarcinoma, 7% (Fig. 194-2); and embryonal carcinoma, 6% (Fig. 194-3). Eleven percent of tumors contained a mixture of histologies. Non–germ cell components, usually sarcoma or epithelial carcinoma, were found in 26 of 45 teratocarcinomas (58%).

The pathologic features of mediastinal nonseminomatous germ cell tumors differ in several ways when compared with their counterparts arising in the testis. First, the occurrence of pure endodermal sinus tumor is extremely rare in the testis, whereas it accounts for up to 35% of mediastinal nonseminomas. Second, the incidence of embryonal carcinoma is much higher in the testis than in the mediastinum. Finally, the occurrence of non–germ cell histologies within mediastinal germ cell tumors is more common than in testicular tumors.

Clinical Characteristics

Malignant mediastinal nonseminomatous germ cell tumors are characterized clinically by rapid local growth and early metastasis to distant sites. At the time of diagnosis, most patients have symptoms caused by compression, invasion, or both of local mediastinal structures. In addition, large series reported by Hainsworth,25 Israel,32 and Logothetis41 and their colleagues have shown that 85% to 95% of these patients have at least one site of metastatic disease at diagnosis and that presenting symptoms are frequently caused by metastases. Common sites of metastases include lung, pleura, lymph nodes (supraclavicular and retroperitoneal), and liver. Bone, brain, and kidneys are less frequently involved. Sickles and associates59 have noted that patients whose tumors contain choriocarcinoma elements may experience catastrophic events related to uncontrolled hemorrhage, such as intracranial hemorrhage or massive hemoptysis. Gynecomastia is present in some patients who have high serum levels of human chorionic gonadotropin (HCG). Constitutional symptoms—such as weight loss, fever, and weakness—are more common in patients with nonseminomatous tumors than in those with pure seminoma.

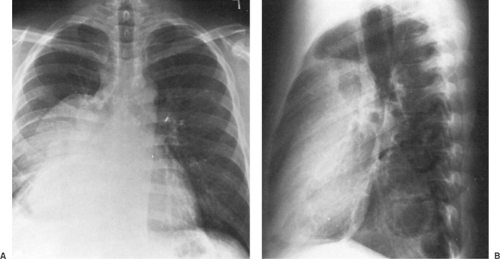

The chest radiograph at diagnosis usually reveals a large anterior mediastinal mass but shows no features that distinguish nonseminomatous germ cell tumors from other mediastinal neoplasms (Fig. 194-4). Levitt and colleagues40 reported that computed tomography (CT) usually shows an inhomogeneous mass with multiple areas of necrosis and hemorrhage (Fig. 194-5), differing from the usually homogeneous appearance of pure mediastinal seminoma. Envelopment of the blood vessels is also often present (Fig. 194-6).

Figure 194-4. A,B: Posteroanterior and lateral chest radiographs of a large anterior mediastinal mass. Right pleural effusion is present. The alpha-fetoprotein level was 35,000 U, but the human chorionic gonadotropin level was normal. Biopsy revealed mixed embryonal and endodermal sinus (yolk sac) elements. Complete remission followed combination chemotherapy of bleomycin, etoposide, and cisplatin.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree

Get Clinical Tree app for offline access

Get Clinical Tree app for offline access

|