Nonmalignant Pleural Effusions

INTRODUCTION

Nonmalignant pleural effusions develop as a consequence of diverse extrapleural conditions that secondarily affect the pleural space. These disorders include systemic diseases (e.g., lupus), disorders of individual organ systems (e.g., chronic pancreatitis, congestive heart failure [CHF]), trauma and surgery, and iatrogenic interventions (e.g., drug related). Pleural fluid (PF) collects by one or more mechanisms: (1) pleural injury that causes increased pleural membrane permeability and protein-rich exudates, (2) increased intravascular hydrostatic forces and/or decreased oncotic forces that cause protein-poor transudates, and (3) extravasation of fluid from lymphatic or vascular structures or from an adjacent body compartment into the pleural space.1

Determining the etiology of a pleural effusion requires a sequential approach that begins with a detailed history and physical examination. Exposures and past occupations (e.g., tuberculosis, asbestos), underlying known conditions (e.g., rheumatoid arthritis [RA], CHF, pneumonia), and subtle symptoms related to a disorder not yet diagnosed (e.g., muscle weakness from myositis) may suggest the probable cause of an effusion. A thorough physical examination may detect abnormal nails with lymphedema suggesting yellow nail syndrome (YNS) or a malar rash indicating lupus pleuritis. Often the history and physical examination provide more diagnostic information than PF analysis or pleural biopsy, which may be nondiagnostic.

A differential diagnosis formulated from the history and physical examination guides a focused evaluation with imaging studies. Initial studies may examine nonpleural structures rather than the pleural space itself. Echocardiography, for instance, may establish CHF or pericarditis as the cause of a pleural effusion. Abdominal computerized tomography (CT) may detect hydronephrosis that underlies urinothorax. Among pleuropulmonary imaging studies, ultrasonography (US) and chest CT with pleural phase contrast enhancement provide detailed examinations of the pleural space, lung, diaphragm, and mediastinal structures that surpass the diagnostic value of standard chest radiography.

Portable US is highly sensitive and accurate for detecting and measuring the volume of PF.2 It also gauges pleural thickness and defines pleural masses, loculations, and the viscosity of PF for diagnostic purposes, guiding thoracentesis and pleural biopsy. Chest CT allows imaging of interlobar and paramediastinal pleural surfaces beyond the reach of US in addition to associated lung abnormalities.3 Like US, CT imaging can guide pleural biopsy and interventions to drain the pleural space. CT angiography allows the diagnosis of pulmonary embolism, which is increasingly recognized as a cause of exudative effusions.4

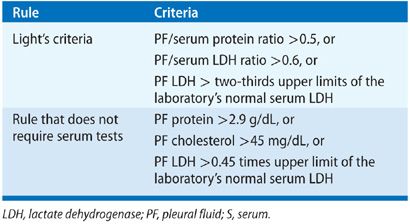

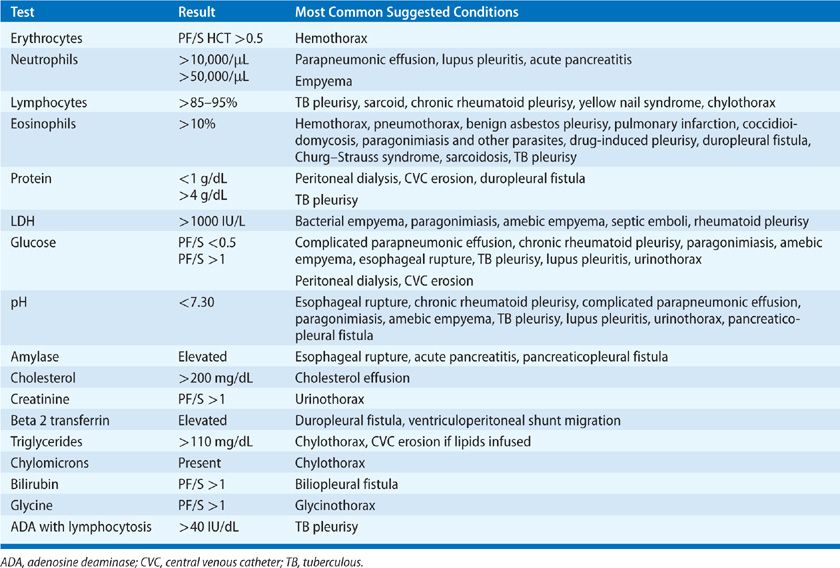

Thoracentesis is indicated for all patients with an undiagnosed pleural effusion in the presence of >1 to 2 cm of layering fluid detected by imaging studies unless CHF is the probable cause. Categorization of the fluid as a transudate or exudate simplifies the differential diagnosis, because conditions associated with PF formation tend to cause effusions of one of these types. Light’s three-criteria rule has been the traditional approach for identifying exudative effusions (Table 76-1). Although the Light’s criteria rule has a high sensitivity; it requires blood tests, suffers from mathematical coupling with two of its criteria, both using PF lactate dehydrogenase (LDH), and misclassifies with its modest specificity up to 30% of patients, when any one of the three test results return values close to its cutoff point (e.g., 15% of malignant effusions misclassified as transudates).5 Alternative rules listed in Table 76-1 avoid some of these limitations and perform equally well as Light’s criteria.6–9 A battery of routine and specialized PF tests may be indicated depending on the pre-thoracentesis differential diagnosis (Table 76-2).

Pleural biopsy provides diagnostic value for patients with exudative effusions who remain undiagnosed after thoracentesis. Approaches to pleural biopsy include closed needle biopsy with an Abrams needle, which is indicated when tuberculous pleuritis is likely, image-guided percutaneous pleural biopsy, and biopsy by video-assisted thoracoscopic surgery (VATS), medical thoracoscopy, or pleuroscopy.10,11

CAUSES OF PLEURAL EFFUSIONS THAT ARE USUALLY TRANSUDATES

A number of causes of transudative pleural effusions have been recognized. Each is discussed below.

CONGESTIVE HEART FAILURE

CONGESTIVE HEART FAILURE

CHF represents the most common cause of transudative effusions, present in 50% to 90% of patients hospitalized for CHF.12,13 PF accumulates when elevated left atrial pressure generates pulmonary edema that provokes leakage of interstitial lung water down a hydrostatic pressure gradient into the pleural space.14,15 Left ventricular failure has been considered an essential factor for producing CHF-related effusions.16 However, small pleural transudative effusions may occur in ~20% of patients with pulmonary arterial hypertension and isolated right ventricular failure,17 which may develop because raised systemic venous pressures increase fluid filtration from chest wall veins into the pleural space and/or impede egress of PF via parietal pleural lymphatics.

Pleural effusions due to CHF are usually bilateral (60%–85%); unilateral effusions are more commonly right sided in a 2-to-1 right-to-left ratio.18 Although CHF is the most common cause of bilateral pleural effusions,18 bilateral effusions in the absence of cardiomegaly suggest a malignant etiology. PF may collect in interlobar fissures and produce the imaging finding of a “pseudotumor.”

Typical presentations of CHF warrant a trial of diuresis and monitoring for resolution of PF. Thoracentesis is indicated for evaluating atypical clinical presentations and failure of PF to resolve. PF is characteristically a transudate. Up to 30% of effusions, however, fulfill Light’s criteria for an exudate for several possible reasons.19,20 Most commonly, a coexisting condition that causes exudative effusions, such as pneumonia or pulmonary embolism, is the actual cause of the effusion.21 Less commonly, diuretic therapy for CHF promotes more rapid reabsorption of intrapleural fluid as compared with protein and LDH, which creates a concentrating effect on PF. Finally, some CHF-related effusions have PF erythrocyte count >10,000/μL, which causes sufficient release of LDH from red cell autolysis to fulfill Light’s criteria for an exudate.22 Several strategies exist to determine that an exudative effusion in the setting of CHF is due to heart failure rather than a comorbid condition (Table 76-3).

Pleural effusions due to CHF gradually resolve as cardiac performance improves with therapy. Patients with large, symptomatic effusions may benefit from therapeutic thoracentesis when a response to cardiac therapy is delayed. Rarely, effusions in patients with refractory heart failure may require pleurodesis to manage PF-related respiratory symptoms, but outcomes data for this approach are limited.30 Placement of a tunneled catheter for intermittent drainage at home provides additional palliative support.31–33

HEPATIC HYDROTHORAX

HEPATIC HYDROTHORAX

Hepatic hydrothorax defines a transudative effusion in a patient with cirrhosis and portal hypertension in the absence of another explanation for the effusion.34 Although only 6% of patients with cirrhosis and portal hypertension have clinically apparent hepatic hydrothorax,35–37 15% of cirrhotics have evidence of effusions when examined by CT or US.38

Hepatic hydrothorax develops when ascites accumulates, raising intraperitoneal pressure that herniates blebs of peritoneum into the chest through small diaphragmatic stomata. When these blebs burst, ascites flows from the relatively high-pressure peritoneal space into the lower-pressure pleural space.39 Because stomata occur more commonly in the tendinous portion of the right hemidiaphragm as compared with the thicker and more muscular left hemidiaphragm, 80% of hydrothoraces are right sided, 18% left sided, and 2% bilateral.40 Although 20% of patients will not have clinically apparent ascites because most of the ascites fluid has decompressed into the pleural space,41 US or CT will demonstrate residual ascites in nearly all patients.42

The clinical presentation of hepatic hydrothorax ranges from an incidental radiographic finding to varying degrees of dyspnea, which depends on the volume of PF, the volume of ascites that stiffens the diaphragm, and presence of underlying cardiopulmonary disease. Rapid-onset respiratory failure may rarely occur when ascites suddenly ruptures into the pleural space.43

Diagnosis requires thoracentesis to profile PF as transudative and exclude other causes of pleural effusion. Thoracentesis presents a low risk of complications despite the presence of cirrhosis and coagulopathy.44 PF is transudative by Light’s criteria in 90% of patients,19 although PF protein levels are usually higher than the concomitant protein concentration in the ascites fluid because of a concentrating effect.45 Diuretic therapy may convert a transudative pleural effusion to an exudate akin to the diuretic effect in CHF.19 Correct classification as a transudate may require calculation of protein and/or albumin gradients as commonly done for CHF patients (Table 76-3).20 Any suspicion of a true exudate, however, warrants evaluation for an empyema or tuberculosis. Although injection of a radionuclide tracer into ascites fluid may detect tracer flow from the abdomen to the chest, scintigraphy confirmation of the diagnosis is usually unnecessary.

Treatment centers on limiting sodium retention and lowering portal vein pressures. Therapeutic thoracentesis provides only transient relief of dyspnea because effusions rapidly recur making paracentesis preferred initial management for symptomatic patients. Chest tube drainage is avoided because of risks of massive fluid loss and poor healing of the chest wall tract after chest tube removal.46–48 Transjugular intrahepatic portosystemic shunts may decrease PF in 88% of patients, but the 1-year survival is only 50%.49–55 Hepatic hydrothorax does not represent a contraindication for liver transplantation.53 Failing other interventions, VATS for closure of diaphragmatic fenestrations and performing talc pleurodesis may benefit some patients, but the risks of this procedure are high.56–58 Chemical pleurodesis by chest catheter or VATS is challenging because of the rapid reaccumulation of PF that prevents apposition of pleural membranes.59–61 Tunneled pleural catheters may provide palliation.62 Spontaneous infection of a hydrothorax represents an important complication being found in 15% of patients admitted with cirrhosis and pleural effusions.38,42 PF features of this condition include a PF neutrophil count >250 cells/μL with a positive PF culture or a PF neutrophil count ≥500 cells/μL with a negative culture in the absence of pneumonia.49

CONSTRICTIVE PERICARDITIS

CONSTRICTIVE PERICARDITIS

More than 50% of patients with constrictive pericarditis develop a pleural effusion that can be the presenting manifestation of pericardial disease.63–65 The pathogenesis of the effusions is unknown but may relate to migration of coexisting ascites into the pleural space or compromised left ventricular function that causes a CHF-related effusion. Both of these mechanisms would cause a transudative effusion.63 Exudative effusions65 and chylothoraces,66,67 however, can also occur. PF may be bilateral or unilateral, with equal side distribution when unilateral.64

RENAL

RENAL

Nephrosis

A transudative pleural effusion may develop in patients with nephrotic syndrome because of severe hypoalbuminemia. The effusions are typically small and bilateral in distribution.68 Larger effusions require the exclusion of pulmonary thromboembolism (PTE) because of the high risk of this condition in nephrosis.

Urinothorax

Urinothorax occurs when urine dissects from the retroperitoneal space into the pleural space most often as a consequence of obstructive uropathy at the level of the bladder or urethra. Obstruction at the renal or ureteral level may produce urinothorax in the presence of a nonfunctioning contralateral kidney.69 Other causes include kidney biopsy, renal transplantation, lithotripsy, failed tube nephrostomy, urinary tract malignancies, retroperitoneal trauma, and surgical complications.69,70 Patients present with mild to moderate respiratory symptoms due to the space occupying effects of the effusion, which are usually unilateral.69,71

PF looks and smells like urine and meets definitions of a transudate by a low protein concentration. The PF LDH, however, is often elevated into the exudative range.70,72 The PF pH73 and glucose74 values may be low, making urinothorax the only cause of a low pH and low glucose transudate in the absence of systemic acidemia and hypoglycemia. The PF/serum creatinine ratio is greater than 1 (mean value >10 in reported cases) in all instances, although the specificity of this finding is less than 100%.70 Elevated ratios in other conditions, however, are closer to 1. Renal scintigraphy can demonstrate tracer flow from the urinary tract to the pleural space to establish the diagnosis. Urinothoraces typically resolve with relief of urinary obstruction.

Peritoneal Dialysis

Pleural effusions develop as a consequence of peritoneal dialysis (PD) in 2% to 10% of patients75,76 with 88% being right sided and a minority bilateral.76 Effusions range in size from small to moderate with 75% of patients having dyspnea,76 but effusions may be massive.77 PF forms due to the migration of dialysate from the relatively high-pressure peritoneal cavity into the low-pressure pleural space.78 Clinicians may note decreased effectiveness of ultrafiltration as the first sign of migration of dialysate into the pleural space.

PF is transudative with a PF protein <0.5 g/dL and glucose >200 to 2000 mg/dL.79,80 PF-to-serum glucose gradients range from 1 mg/dL to 1885 mg/dL with 20% of patients having gradients <50 mg/dL.81 The PF/serum glucose ratio is always >1.81 Peritoneal scintigraphy using technetium-99 m tagged macroaggregated albumin (28–30) or Tc-99 m sulfur colloid detects the flow of dialysate into the pleural space.75,77,82 Management begins with reduction of dialysate volume or temporary discontinuation of PD.75,83,84 Discontinuation of PD for 4 to 6 weeks may allow diaphragmatic conduits to heal.85 Up to 58% of patients may resume PD without recurrence of their effusions.86,87

CENTRAL NERVOUS SYSTEM

CENTRAL NERVOUS SYSTEM

Cerebrospinal Fluid Leakage into the Pleural Space

Cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) can leak into the pleural space when a duropleural fistula forms from a malignancy or after spinal surgery (particularly cervical laminectomy),88 thoracic surgery,89 or blunt or penetrating trauma.90 Symptoms include dyspnea, meningitis,91 CSF pressure headaches,91 and various neurologic symptoms.89,91 PF appears as clear as CSF with essentially no cells and a PF protein <1 g/dL, low LDH, and glucose and pH values similar to serum. Beta-2 transferrin is a protein found in CSF and inner ear perilymph that has a sensitivity and specificity of 100% and 95%, respectively for establishing CSF-related effusions.92 Duropleural fistulae rarely heal spontaneously and present risks for CNS infection and pneumocephalus. CT myelography can visualize the fistula tract in preparation for surgical repair.89,93

Ventriculoperitoneal Shunts

Pleural effusion is a rare complication of ventriculoperitoneal (VP) shunting that occurs most commonly in children but has been reported in adults.94 PF accumulates either from migration of the shunt catheter into the thorax94–100 or from flow of CSF ascites into the pleural space.95,100–102 PF analysis demonstrates no cells, a low protein and LDH content, and presence of beta-2 transferrin.102,103 A radionuclide shuntogram can confirm the diagnosis.104 Reports also exist of fibrothorax,105 tension hydrothorax,106 bronchopleural fistulae,107 and empyema108 subsequent to migration of a VP shunt.

PLEURAL

PLEURAL

Trapped Lung

Remote pleural inflammation that causes fibrotic membranes to form on the visceral pleura can prevent lung expansion and create negative intrathoracic pressures that cause a hydrostatic gradient for PF formation.109,110 A trapped lung should be suspected when PF drains incompletely by thoracentesis or recurs quickly and when a hydropneumothorax forms after thoracentesis with a similar configuration of the lung margin as compared with the pre-thoracentesis chest radiograph. Because of the chronic nature of the effusion, most patients are asymptomatic. The PF is usually a transudate. If sampled during the early formation of a trapped lung when inflammation may be present, the effusion may be exudative.111 Pleural manometry performed during thoracentesis demonstrates rapid drops in measured pleural pressure as fluid is removed with calculated lung elasticity values >14.5 cm H2O/L. A CT scan shows thickened visceral pleural membranes.110 For patients with dyspnea, surgical decortication can be considered to allow lung reexpansion. Patients must be evaluated thoroughly for other causes of dyspnea, considering the difficulty and risks of decortication for established trapped lungs.109

PROCEDURAL IATROGENOSIS

PROCEDURAL IATROGENOSIS

Central Venous Catheter Migration

Initial misplacement of central venous catheters into the mediastinum or subsequent erosion of catheters through vascular walls allows infusates to flow into the mediastinum and subsequently the pleural space.112–117 The resulting unilateral or bilateral pleural effusions vary in size depending on the rate of fluid infusion. Unilateral effusions may be ipsilateral or contralateral to the catheter insertion site.112 Various catheter configurations apparent on chest radiographs and CT studies may identify patients at risk for catheter erosion.112,118,119 The PF profile reflects the nature of the infusate with glucose containing solutions having a PF/serum glucose ratio >1.112 Infusion of lipid-containing formulations causes increased pleural triglyceride levels. Most infusates are low in protein so PF protein is <1.0 g/dL. Infusion of chemotherapeutic agents into the pleural space may cause an inflammatory exudate and acute chest pain.120

Glycinothorax

Right-sided pleural effusions may rarely occur in patients undergoing bladder instrumentation with bladder irrigation using glycine solutions.121,122 Perforation of the bladder allows glycine solutions to pass through the peritoneal cavity into the pleural space. The PF is a sanguineous transudate with a high concentration of glycine.

VASCULAR

VASCULAR

Pleural effusions may develop in 13% of patients with isolated right heart failure due to pulmonary arterial hypertension.17 Most of the effusions are trace to small (63%) and right sided in 58% and bilateral in 26%. Of the four patients reported with thoracentesis, all of the effusions were transudates.

Pulmonary veno-occlusive disease is a rare condition associated with specific pathologic changes of the postcapillary (venous) pulmonary circulation that produce pulmonary arterial hypertension.123 Chest CT commonly detects unilateral or bilateral pleural effusions in this condition.123–127 The nature of the effusions is uncertain but presumed to be transudative because of the raised pulmonary venous hydrostatic forces. Pulmonary capillary hemangiomatosis has also been reported to cause pleural effusions and presumed to be transudative in nature.124,128

CAUSES OF PLEURAL EFFUSIONS THAT ARE USUALLY EXUDATES

A number of causes of exudative pleural effusions have been recognized. Each is discussed below.

PATHOGEN RELATED

PATHOGEN RELATED

Parapneumonic Effusions

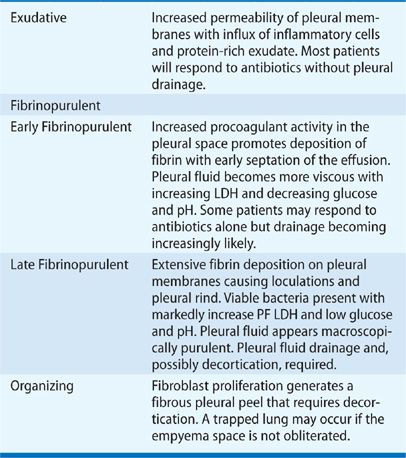

Twenty to 57% of patients hospitalized for community-acquired pneumonia develop a parapneumonic effusion,129,130 as defined by a pleural effusion caused by pneumonia. PF forms when inflammatory cells migrate to the pleural space from an adjacent zone of lung infection and release proinflammatory mediators that alter pleural membrane permeability and recruit additional inflammatory cells.131–133 An influx of protein-rich fluid creates an initially sterile, free-flowing effusion. Subsequent invasion of bacteria promotes a procoagulant effect in PF, which generates fibrin132–134 that deposits on pleural surfaces and begins the formation of intrapleural loculations and a pleural rind. Infected PF eventually evolves into pus and a frank empyema. Although the development of an empyema represents a continuous sequence of pathophysiologic events, it has been arbitrarily described as a three-stage process to assist management (Table 76-4).135 Parapneumonic effusions have also been classified as “uncomplicated” (treatable by antibiotics alone) or “complicated” (pleural space drainage is required).136,137

The incidence of pleural infections has increased during the last several decades across all age groups138–140 with 30-day mortality that ranges from 5% to 27% depending on the extent of intrapleural suppuration, patient age, and presence of comorbid conditions.138,140–142 Risk factors for parapneumonic effusions include diabetes, immunosuppression, alcoholism, cancer, poor dental hygiene, and increased severity of the index pneumonia.130

Signs and symptoms of a parapneumonic effusion merge with those of the underlying pneumonia with fever, productive cough, and dyspnea predominating. Pleuritic chest pain increases the probability of a parapneumonic effusion and, along with tachycardia and leukocytosis above 15,000/mm3, increases risk that the effusion is complicated.99 Subacute or chronic constitutional symptoms of malaise, anorexia, and weight loss with fetid breath represent characteristic findings of an anaerobic empyema. Failure of a patient with pneumonia to respond to antibiotics as expected suggests the possibility of a partially treated empyema.

Chest imaging identifies approximately 90% of clinically significant parapneumonic effusions.143,144 Most effusions are apparent as a dependent fluid collection with a meniscus on standard two-view chest radiographs. The only radiographic sign of an effusion, however, may be obscuration of a diaphragm that may be incorrectly attributed to lower lobe consolidation.144 Consequently, a parapneumonic effusion should be suspected and evaluated by US in the presence of a diaphragmatic silhouette sign. Presence of intrapleural air-fluid levels indicates a bronchopleural fistula with empyema. A loculated effusion in a nondependent location suggests a complicated parapneumonic effusion.

US has a higher sensitivity and specificity for detecting PF as compared with standard radiographs.145–148 Echogenic PF and septations suggest the presence of a complicated parapneumonic effusion in the fibrinopurulent or organizing stage and thereby increasing the likelihood that drainage will be required.149–152 Ultrasound also allows image-guidance for thoracentesis, which improves the success and safety of the procedure in the presence of pleural loculations.153,154 Contrast-enhanced chest CT can establish the presence, location, and extent of parapneumonic effusions for patients with complex PF collections and uncertain radiographic and US findings.3,143 Loculated empyemas with interlobar and paramediastinal fluid collections can only be imaged by chest CT. Characteristic CT findings include the “split pleura sign” (enhanced pleurae that surround a loculated effusion), pleural thickening, and increased attenuation of extrapleural subcostal fat.143 Chest CT can also differentiate between an empyema and a peripheral lung abscess adjacent to the chest wall.155 Ultrasound, however, is more sensitive as compared with chest CT for detecting septations.

Thoracentesis and PF analysis to provide diagnostic and therapeutic information are indicated when PF is greater than 1 to 2 cm in depth by US or decubitus radiographs.156,157 PF may appear grossly turbid, serosanguineous, or frankly purulent. A fetid odor suggests an anaerobic empyema. Appropriate PF tests with their clinical implications are listed in Table 76-5. PF procalcitonin levels do not provide value in guiding drainage decisions.158,159 Clinical practice guidelines recommend basing the decision to drain a parapneumonic effusion on a combination of clinical, imaging, and PF findings (see Chapter 127).160,161

Uncomplicated parapneumonic effusions resolve after effective antibiotic therapy for the underlying pneumonia. Although it is widely accepted that complicated parapneumonic effusions by definition require drainage of infected PF, consensus does not exist regarding the initial approach to drainage.168 Insertion of an image-guided, small-bore (<15 Fr) intercostal catheter connected to suction and flushed with saline every 6 hours provides effective therapy for many patients.169–171 Limited data indicate that viscous effusions that fail to drain after catheter insertion may subsequently drain with intrapleural instillation of tissue plasminogen activator (tPA) to lyse fibrin adhesions and deoxyribonuclease (DNase) to thin PF.172–176 Up to 30% of complicated parapneumonic effusions, however, require surgical drainage either by VATS or thoracotomy, depending on the degree of loculation, extent of pleural peels and need for debridement or decortication, and operability of the patient.177 Studies have not validated any clinical or imaging findings that reliably identify patients who are unlikely to respond to catheter drainage and should be triaged directly to surgical drainage.163 Moreover, studies have not demonstrated advantages with surgery as a routine, first-line therapy for empyema.178,179 Regardless of the drainage approach adopted, unnecessary delays in draining infected PF increase hospital stay, morbidity, and mortality.180–183 Organized empyemas may require more extensive surgery to promote long-term open drainage and eventual closure of the empyema cavity.184

Tuberculous Pleurisy

Tuberculous pleurisy can occur with primary infection or as reactivation disease.185 It accounts for 30% to 80% of all pleural effusions in developing countries and occurs in up to 30% of patients who present with pulmonary tuberculosis.186,187 Its prevalence is lower in developed nations accounting for 1% of all pleural effusions and occurring with pulmonary tuberculosis in only 3% to 5% of patients.186 HIV-positive patients, however, have a higher incidence of tuberculous pleurisy presenting with underlying pulmonary tuberculosis.188 Patients with tuberculous pleurisy commonly resolve their effusions spontaneously but present within 2 years with pulmonary tuberculosis.189,190

PF develops from an intrapleural hypersensitivity response to mycobacterial antigens released by rupture into the pleural space of a subpleural caseous focus.191,192 The number of viable acid-fast organisms in PF is insufficient to allow reliable diagnosis by standard PF staining and culture techniques. Patients present with subacute symptoms characterized by cough, pleuritic chest pain, dyspnea, and fever; although some patients present more acutely simulating bacterial pneumonia and others more indolently with weight loss and fatigue. Purified protein derivative skin tests are positive in only 50% of patients but usually convert to positive within 2 months.193,194 The effusion is usually unilateral encompassing less than two-thirds of the hemothorax.194 Standard chest radiographs and chest CT scans detect active parenchymal tuberculosis in 20% and 80% of patients, respectively.194,195

Any undiagnosed exudative pleural effusion should prompt consideration of tuberculous pleurisy with highest suspicion for lymphocyte predominant effusions (>60% lymphocytes) with protein concentrations >5 g/dL.196 Up to 17% of patients, however, have lymphocyte percentages <50%.196 The PF cell differential may be neutrophil predominant within the first 2 weeks of symptom onset.197 PF mesothelial cell percentages are nearly always <5%.198 PF glucose and pH mirror serum levels although some patients have PD levels lower than serum.

PF staining for acid-fast organisms has a low yield except in the presence of HIV-infection wherein 20% may be smear positive.199 Although PF culture has traditionally been reported to have a sensitivity <50%,194,200,201 studies using liquid culture techniques report a sensitivity of 63% to 75%.196,202 Sputum mycobacterial cultures may be positive in >50% of patients196,203 with positivity of either sputum and/or PF cultures in 79%.196

Adenosine deaminase (ADA) is found in increased concentrations in tuberculous effusions and some other inflammatory and neoplastic pleural conditions. In regions with a high prevalence of tuberculosis, a PF ADA >40 IU/L in a lymphocyte predominant effusion confirms tuberculous pleurisy,200,201,204–206 allowing a diagnosis for 90% of patients after a single thoracentesis.10 An ADA value <40 IU/L adequately excludes the diagnosis in high prevalence settings.207 In regions with low or intermediate prevalence of tuberculosis, PF ADA assay has insufficient sensitivity and specificity, and most patients with negative PF microbiologic evaluations require pleural biopsy.10,208–210 Although elevated ADA concentrations in the pleural space represent the ADA2 isoform, ADA2-specific PF assays provide only negligible benefits over ADA.211 Although several other biomarkers (interferon-gamma, interferon-gamma–induced protein of 10 kDa, and dipeptidyl peptidase [DPP] 4 levels in unstimulated PF) provide similar diagnostic value as compared with PF ADA,212–216 none has comparable availability for routine use.215,217,218 Commercially available T-cell interferon-gamma release assays performed on both blood and PF have inadequate diagnostic accuracy219,220 as do PF nucleic acid amplification tests.216,221,222

Pleural biopsy may be required in complicated settings. Tuberculous granulomata are diffusely distributed over pleural surfaces, which allows up to 70% to 87% of patients to be diagnosed by closed (blind) needle biopsy using an image-guided Abrams needle technique.194,200,200,223–226 This approach is appropriate when the pretest probability of tuberculosis is high for an undiagnosed exudative pleural effusion.201 Six pleural biopsies are recommended.201,224 For other patients, thoracoscopy provides a 100% diagnostic yield.200,201,208 Biopsied pleural tissue must be cultured for acid-fast organisms and examined for organisms and granulomata. Microscopic-observation drug-susceptibility culture as compared with Lowenstein–Jensen culture has a higher diagnostic yield.227

Drug therapy for tuberculous pleurisy is the same as for pulmonary tuberculosis with a four-drug regimen for susceptible organisms.228 Evidence does not support a role for adjunctive corticosteroids.229 When examined with chest CT after chemotherapy, nearly 70% of patients will have some degree of residual pleural thickening that may contribute to measureable pulmonary restriction.230 Some experts recommend therapeutic thoracentesis to prevent pleural fibrosis for moderate to large tuberculous effusions,228 although evidence of benefit is uncertain.231,232 Ultrasonographic detection of complex septated pleural space, CT evidence of extrapleural fat proliferation or loculated effusion, and long duration of symptoms at initiation of therapy may identify patients at greatest risk of pleural thickening 1 year later.230,233

Pleural Effusions Caused by Viral Infections

Acute viral respiratory infections may be associated with transient pleural effusions. The incidence of viral-related pleural effusions is unknown because most patients have a mild clinical course and do not undergo testing for viruses or imaging studies. Recent case series that review the chest studies of patients with documented viral pneumonias, however, demonstrate a low incidence of pleural effusions.234–236 The presence of a pleural effusion in a patient suspected with viral pneumonia and sufficiently ill to require hospitalization, therefore, should prompt consideration of a bacterial coinfection and a parapneumonic effusion. Notably, pneumonia due to swine-origin influenza A (H1N1) is commonly associated with pleural effusions.237,238

Fungal and Parasitic-Related Pleural Effusions

A wide spectrum of fungal infections causes pleural effusions in diverse clinical settings. Immunocompromised hosts may develop fungal empyema secondary to pleural seeding from a fungal pneumonia or more distant sites of infection. Common pathogens include Aspergillus239,240 and Cryptococcus species.240,241 Cryptococcal pleuritis suggests the presence of disseminated disease.241 In immunocompetent patients, chylothoraces may occur secondary to mediastinal granulomatous disease caused by Histoplasma capsulatum.242 Patients with allergic bronchopulmonary aspergillosis may develop eosinophilic pleural effusions242 or erosion of fungus balls into the pleural space.243,244 Finally, pulmonary fungal infections may lead to pleural effusions, which may be sterile or infected with fungal elements. Coccidioidomycosis represents the most common and distinctive endemic fungus presenting in this manner.245,246 Fifteen percent of patients hospitalized with acute pulmonary coccidioidomycosis have pleural effusions247,248 with nearly a quarter of patients progressing to empyema.248 PF is exudative with eosinophilia being commonly present.248

Anecdotal reports exist of a broad range of parasitic infestations associated with pleural effusions.249–257 Among these, pleural effusions related to rupture of an amebic liver abscess across the diaphragm into the pleural space producing an empyema258 and pulmonary infestation with Paragonimus (a genus of flatworms)254,256,259,260 are the most common. Amebic empyema is most commonly right sided, with PF having an anchovy paste or chocolate-milk appearance. A reactive pleural effusion can also occur secondary to transdiaphragmatic inflammation.257 Paragonimiasis produces pleural effusions and pulmonary parenchymal changes that may simulate malignancies or tuberculosis.256 Chest CT series indicate that pleural effusions are the most common intrathoracic imaging findings of the North American form of paragonimiasis (Paragonimus kellicotti).259 PF has a markedly increased LDH and may also assume characteristics of a chylothorax.251 Blood or PF eosinophilia are variable findings. Pulmonary echinococcosis can produce pleural effusions, hydropneumothorax, and secondary pleural hydatidosis when pulmonary or hepatic echinococcal cysts rupture into the pleural space.257,261 A reactive pleural effusion may also occur because lung echinococcal cysts are usually subpleural in location. PF may be an eosinophilic exudate262 or empyema.263 Other parasites rarely involve the pleural space.257

VASCULAR

VASCULAR

Pulmonary Thromboembolism

Up to 40% of patients with PTE have associated pleural effusions when examined by standard radiographs with 47% having effusions on chest CT images.264–268 Lung ischemia results in increased pleural membrane permeability with an influx of protein-rich fluid into the pleural space; effusions related to PTE are almost always exudates.265,269 Effusions are unilateral in 85% of patients with approximately equal distribution of right- versus left-sided locations occurring ipsilateral or contralateral to the site of the PTE.265,269 Less than 20% of effusions occupy more than one-third of the hemithorax264,265,269 with most only blunting the costophrenic angle. Delayed diagnosis may cause the effusions to loculate.265,270

PF findings are nonspecific with erythrocyte counts greater than 10,000/μL in 67% of patients, neutrophil predominance in 60%, and eosinophil counts >10% in 18%.269 Only 57% have bloody PF.269 Thoracentesis, therefore, has a limited role in evaluating PF for suspected PTE but has value for excluding other conditions, such as pleural infection or hemothorax. PF usually reabsorbs during anticoagulant therapy. The presence of a bloody effusion does not obviate systemic anticoagulation because hemothorax rarely occurs. When pleural bleeding does occur, it presents with sudden cardiopulmonary compromise usually during the first week of anticoagulation.271–273

Nonthrombotic Pulmonary Emboli

Septic Emboli Septic emboli typically lodge in lung periphery, which can cause sterile or infected pleural effusions. Common causes of septic emboli include infected venous catheters,274 septic thrombophlebitis (e.g., Lemmiere syndrome),275 and right-sided endocarditis. Patients with intravenous drug addiction may present with pyopneumothorax.276,277 Common CT imaging findings include peripheral nodules with clearly identifiable feeding vessels and/or air bronchograms, metastatic lung abscesses, and subpleural, wedge-shaped densities with or without necrosis.278–280 PF reflects acute sterile inflammation or evidence of an empyema.281

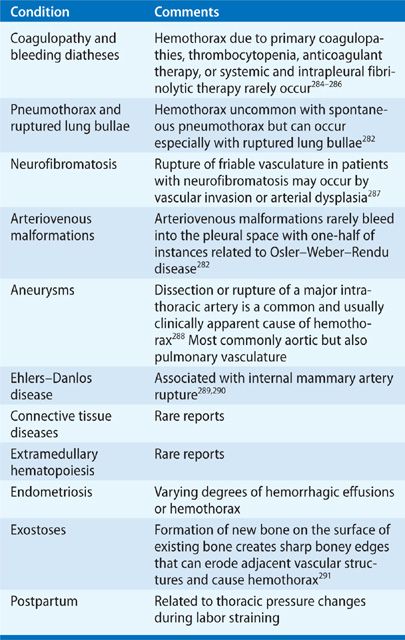

Hemothorax

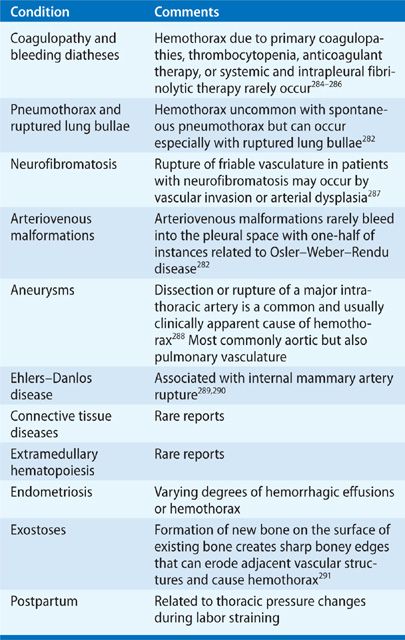

Hemothorax is defined by the presence of bloody PF with a PF hematocrit (hct) >50% of the simultaneous blood hct value.282 Because erythrocytes undergo spontaneous lysis in the pleural space, a PF hct between 25% and 50% measured a few days after the onset of pleural effusion supports the diagnosis. Hemothoraces result from blunt and penetrating chest trauma, procedures that damage vasculature in or near the pleural space, and underlying conditions that promote spontaneous intrapleural hemorrhage (Table 76-6). Hemothorax carries a potential for unabated hemorrhage, respiratory compromise, and shock. Principles of management include drainage of the pleural space by thoracentesis in the absence of ongoing bleeding, or by chest tube to monitor ongoing bleeding rates, removal of intrapleural blood, and prevention of a subsequent trapped lung or empyema. Pleural drainage also apposes pleural membranes to tamponade pleural-based bleeding sites. Patients may require emergency thoracotomy or VATS to control bleeding and evacuate intrapleural clots.283

Catamenial hemothorax represents a unique form of hemothorax occurring in young, multiparous, and menstruating women with pelvic endometriosis.292,293 Two-thirds of patients have intrapleural endometriosis noted during VATS.293 Unilateral and right sided in 80% of instances, bilateral pleural effusions occasionally occur.293 Catamenial pneumothorax294 and hemoptysis293,295 may occur simultaneously with hemothorax. Intrapleural bleeding is usually mild and self-limited, which may delay diagnosis until the temporal relationship with menses is noted. Once diagnosed, most patients are sufficiently stable to allow medical management with hormonal therapies that provide only partial effectiveness.282,296 Patients with recurrent hemothorax may require surgical resection of intrathoracic endometriomas, although relapse commonly occurs.292

Vasculitis

Pleural effusions can occur in granulomatous polyangiitis (GP, also termed Wegener granulomatosus) as a result of primary pleural involvement with necrotizing vasculitis or secondary to renal disease, pneumonia, or CHF as complications of vasculitis.297–299 Small patient series indicate that 10% to 20% of patients with GP have pleural effusions usually as incidental findings.298,300 Patients may rarely present, however, with a pleural effusion301,302 and massive effusions with bronchopleural fistulae have been reported.303 From the limited reports of PF analyses, the effusions are exudates with neutrophil predominance.304,305 Pleural biopsy may detect evidence of granulomatous vasculitis or only nonspecific fibrosis.306,307

Up to 30% of patients in the vasculitic phase of Churg–Strauss syndrome have pleural effusions, although most are small and asymptomatic.308,309 Massive effusions, however, have been reported.310 Only rare reports exist of PF analysis, which characterize the fluid as having increased eosinophils.310–312 One report noted a low pH and glucose.312 Effusions may respond to corticosteroid therapy.312

Pleural effusions rarely occur in patients with giant cell arteritis313–320 and may represent the presenting feature of the disease.313,315,316,320 PF is exudative with neutrophil predominance and a normal glucose, although lymphocyte predominance314 and transudative effusions have been reported.315 Pleural biopsy is nonspecific.317 The effusions respond to prednisone therapy.313,319

Behçet disease is a chronic, relapsing inflammatory disorder of unknown etiology. Vascular involvement represents the major risk for mortality with any sized vessel in the venous, arterial, or capillary circulation being potentially affected. Among a myriad of intrathoracic complications,321 Behçet disease can cause abnormalities of pleural membranes and various types of pleural effusions. High-resolution CT scans commonly detect pleural thickening and nodularity that may represent resolved pulmonary infarctions, spread of subpleural pulmonary inflammation, and/or pleural vasculitis.322–326 Pleural effusions commonly occur in patients with vascular obstruction and can be transudates in patients with superior vena cava (SVC) obstruction327 or chylothoraces in patients with thrombosis of the SVC or other major intrathoracic vessels.328–332 Effusions respond variably to corticosteroid therapy330,331 and may require anticoagulation, immunosuppressive drug therapy,333 and/or pleurodesis.330

Superior Vena Cava Syndrome

More than 60% of patients with SVC syndrome develop pleural effusions that are nearly always exudative in nature, with 18% being chylothoraces.334 The etiology of the effusions is unknown, but increased resistance to lymphatic duct drainage into the brachiocephalic vein may contribute to chylothorax.335 Effusions are equally right sided or left sided and most effusions occupy less than 50% of a hemithorax.335 The effusions usually resolve with resolution of the SVC syndrome.

GASTROINTESTINAL AND INTRA-ABDOMINAL DISORDERS

GASTROINTESTINAL AND INTRA-ABDOMINAL DISORDERS

Pancreatitis and Pancreatic Fistulae

Pleural effusions are apparent in 50% of patients hospitalized with acute pancreatitis.336,337 Several potential mechanisms exist for PF formation, which include release of proinflammatory mediators from the pancreas into the circulation, transdiaphragmatic transit of parapancreatic inflammatory exudates, lipolysis of mediastinal fat, and early formation of pancreaticopleural fistulae.338,339 Early onset of pleural effusions represents a negative prognosticator for acute pancreatitis.337,340,341 The PF profile includes a neutrophil predominant exudate with an elevated amylase usually greater than twice the serum value.342

Predominantly left-sided effusions may develop in patients with chronic pancreatitis who develop a pseudocyst with a sinus tract through the retroperitoneum into the pleural space. Most patients are male (70%) with a history of chronic alcoholic pancreatitis (50%), but other causes of pancreatitis, such as choledocolithiasis, also occur.343 Patients present with dyspnea (65%), abdominal pain (29%), cough (27%), and chest pain (23%).344 PF pancreatic amylase is markedly elevated (>1000 IU/L). Visualization of the pancreaticopleural fistula with its drainage into the pleural space can be achieved by helical CT scanning, endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography, or magnetic resonance cholangiopancreatography (MRCP) with MRCP being the most sensitive initial examination.343–348

No validated algorithm for treatment of pancreaticopleural fistula exists, but most centers initiate a sequential approach that begins with alimentary nutrition and observation supplemented with octreotide to suppress exocrine secretion.345,347–349 Thirty-five percent of patients will fail conservative therapy and require endoscopic placement of a pancreatic stent followed by surgery, if the stent is unsuccessful.343,344,346–348,350 Prolonged medical therapy only delays recovery, so patients should be evaluated for definitive operative intervention early in the course of treatment.343

Esophageal Perforation

Rupture or perforation of the esophagus with decompression of gastroesophageal contents into the pleural space represents a life-threatening condition. Esophageal disruption results from forceful vomiting (Boerhaave syndrome), esophageal lesions (retained foreign bodies or neoplasms), or esophageal instrumentation (endoscopy, gastric banding for weight loss).351 Boerhaave syndrome presents with chest pain and signs of sepsis with a rapidly progressing, usually left-sided effusion. Meckler’s triad of vomiting, chest pain, and subcutaneous emphysema suggests the diagnosis. Imaging studies demonstrate a rapidly progressing pleural effusion or hydropneumothorax often associated with mediastinal, paraesophageal, and/or subcutaneous emphysema.352,353 PF findings include high salivary amylase, low pH, low glucose, high LDH, and evidence of pleural infection. Cytologic examination may identify food particles and/or squamous epithelial cells.354 Gastrograffin-contrasted chest CT or endoscopy may localize the esophageal injury and fistula tract, but negative studies do not exclude the diagnosis. Adequate surgical debridement with drainage of the mediastinum and pleural space within 24 hours of presentation improves outcome in Boerhaave syndrome.355,356 Iatrogenic esophageal perforation may be managed more conservatively.357

Endometriosis

Endometriosis involving the peritoneum complicated by ascites may rarely cause a pleural effusion that is characteristically right sided with bloody or chocolate-brown appearing PF.358,359 The effusions are linked temporally with menses and contain hemosiderin-laden macrophages. In contrast to catamenial hemothorax due to intrathoracic endometriosis, this condition is characterized by endometrial tissue that is confined to the abdominopelvic region with secondary flow of fluid into the pleural space.

Intra-Abdominal Diseases

Infradiaphragmatic abscesses and various ischemic and inflammatory lesions of abdominal organs (e.g., perihepititis360 and splenic ischemia361) can cause exudative effusions that may become infected if intra-abdominal pathogens migrate into the pleural space. Depending on the location of the intra-abdominal locus of infection or inflammation, the effusions may be predominately right sided (e.g., hepatic abscess) or left sided (e.g., splenic abscess or infarction). CT scanning establishes the diagnosis in most instances and directs both pleural and abdominal drainage.

Biliothorax

Bile can flow into the pleural space causing a right-sided pleural effusion as a complication of percutaneous biliary drainage,362–365 radiofrequency ablation or catheter embolization of liver lesions,366–368 or spontaneous pancreaticopleural or cholecystopleural fistulae.369,370 PF has a green tint with neutrophil predominance and a PF/serum bilirubin ratio >1.

SYSTEMIC DISEASES

SYSTEMIC DISEASES

Connective Tissue Diseases

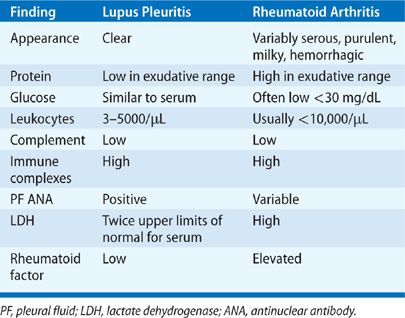

As many as 30% of patients with systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE) experience pleuritis at some time during the course of their disease.371,372 Pleuritis is an independent predictor of mortality in lupus.371 Associated pleural effusions are usually small to moderate, but large effusions can occur. Usually bilateral, they have an equal side distribution when unilateral.373 Concomitant anti-Sm and anti-RNP antibody seropositivity, greater severity and longer duration of lupus, and young age at SLE onset are associated with a higher rate of pleural disease.371 Typical PF profiles are shown in Table 76-7.374,375 Detection of a positive PF antinuclear antibody (ANA) does not provide incremental diagnostic value to a positive serum ANA.376 Rarely, lupus pleuritis may progress to fibrothorax and trapped lung.377 Effusions respond to nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs as initial therapy, or corticosteroids if necessary, in most patients, but pleuritis tends to recur, often on the contralateral side. Refractory massive pleural effusions rarely occur and may require high-dose steroids and cyclophosphamide, intravenous immunoglobulins, and occasionally pleurodesis.378

Pleural involvement is the most frequent manifestation of RA in the chest and causes pleural effusions in up to 20% of patients.373,379 As many as 11% of patients within the first year of RA diagnosis have evidence of pleural thickening or pleural effusions on high-resolution CT imaging.380 Pleural effusions occur most often in men who have active arthritis, subcutaneous rheumatoid nodules, elevated rheumatoid factors, and radiographic evidence of underlying rheumatoid lung lesions.379 Patients with RA may rarely present with pleurisy.381 Pleural effusions are small to moderate in size, more often left sided, and asymptomatic.382 Symptomatic effusions warrant thoracentesis to exclude empyema that can occur spontaneously with RA pleural effusions.379 Sterile RA effusions have the pleural profile listed in Table 76-7. Effusions have a neutrophil predominance at onset but may convert to lymphocytic predominance in 7 to 11 days.383 PF cytology may demonstrate, elongated macrophages and multinucleated giant cells (tadpole cells), and granular debris.383 Sterile RA effusions often have a low glucose (<30 mg/dL) and pH (<7.20) that complicates differentiation from pleural infection. Pleural biopsy may demonstrate replacement of parietal pleural mesothelial cells with a palisade of macrophage-derived cells,383 but biopsy is usually not needed for diagnosis. Most effusions resolve spontaneously but some persist or progress to fibrothorax.379 No therapy has demonstrated value for RA pleural effusions. RA may also cause cholesterol effusions384 and bronchopleural fistulae.385

Although recurrent pleuritic chest pain commonly occurs in patients with Sjögren syndrome,386 pleural effusions rarely develop. Among 343 patients reported with Sjögren syndrome, only 9% had pulmonary manifestations, of which 4 patients had pleural effusions.386 Limited data indicate that the effusions associated with Sjögren syndrome are lymphocyte predominant exudates with high PF levels of anti–SS-A/SS-B antibodies.387 An effusion should suggest lymphoma, which occurs with increased frequency in Sjögren syndrome.

Up to 7% of patients with systemic sclerosis may have a pleural effusion that can result from pleural involvement with sclerodermal tissue changes or secondary causes of pleural effusions associated with scleroderma, such as CHF.388 PF is a lymphocyte predominant exudate unless it is a transudate due to associated CHF or renal failure.388,389

Mixed connective tissue disease (MCTD) has clinical features of SLE, scleroderma, and polymyositis–dermatomyositis and is defined by the presence of high serum titers of antibodies against uridine-rich RNA-small nuclear ribonucleoprotein (snRNP).390 Pleuropulmonary complications commonly occur in up to 50% of patients having pleural effusions and 20% having symptoms of pleurisy.391–393 Pleural effusions are usually incidental imaging findings, but may rarely be the presenting feature of the disease.394 The PF profile is poorly defined, but a report exists of a granulocyte predominant exudate.395

Exudative effusions with normal PF glucose levels have been rarely reported in patients with ankylosing spondylitis.396–399 Associated nonspecific pleuritis has been demonstrated on pleural biopsy specimens.399 Effusions may be transient399 or recurrent.396

Polymyositis and dermatomyositis cause interstitial lung disease in approximately 10% to 20% of patients and have the potential for provoking respiratory failure, especially in patients with the antisynthetase syndrome.400 Although pleural irregularities are noted in a high proportion of patients,401 pleural effusions rarely occur and, when present, invariably exist in association with interstitial lung disease and should prompt consideration of an alternative underlying diagnosis.402–404 The PF profile has been reported to be lymphocyte predominant with rare reports of increased eosinophils.402

Sarcoidosis

Pleural effusions rarely occur in patients with sarcoidosis with a reported prevalence of 0.7% to 10%.405–411 A large case series reported 1.1% prevalence of sarcoid-related effusions in asymptomatic ambulatory patients examined by US.407 Thirty-three percent of patients examined by CT scanning have evidence of pleural thickening and subpleural nodules, which are assumed related to sarcoidosis.412,413 Sarcoid effusions are usually small to moderate sized, unilateral, and asymptomatic although large, symptomatic effusions can occur. Only 20% of effusions are bilateral.407 Most effusions are lymphocyte predominant exudates407,414 with one report of the lymphocyte populations having a high CD4/CD8 ratio.415 Chylothorax,409 eosinophilic effusions,416,417 trapped lung,418 and hemorrhagic effusions419 may occur. Pleural biopsy may demonstrate sarcoid granulomas.405,408,410 Most sarcoid effusions resolve spontaneously.

Myedema

Both transudative and exudative effusions have been reported in patients with myxedema.420–425 Most of these effusions respond to thyroid replacement therapy.

Amyloid

Exudative or transudative pleural effusions can develop from infiltration of amyloid into parietal pleural surfaces, increasing capillary permeability and blocking reabsorption of PF through lymphatic stomata.426,427 Most effusions are associated with light chain amyloidosis. Pleural effusions can also occur through indirect mechanisms of amyloid-induced hypothyroidism, nephrosis, and CHF, the latter two of which may cause transudative effusions in this setting.428 Amyloid-related exudative effusions rarely resolve spontaneously and may require repeated thoracentesis or pleurodesis.

Extramedullary Hematopoiesis

Extramedullary hematopoiesis involving the mediastinum and pleural membranes has been associated with exudative pleural effusions,429–432 hemothorax,433 and chylothorax.434 Detection of normoblasts435 and myeloblasts432 in PF suggests the diagnosis. Symptomatic effusions have been successfully managed by low-dose thoracic radiotherapy, pleurodesis, and hydroxyurea.429,430,434

DRUG RELATED

DRUG RELATED

A wide spectrum of drugs can cause pleural effusions through a variety of mechanisms. A listing of these drugs is available at http://pneumotox.com/indexf.php?fich=clin0&lg=en.

One unique form of drug-induced pleural effusions is represented by ovarian hyperstimulation syndrome (OHSS) that develops during induced ovulation with human chorionic gonadotropin hormone. This condition is characterized by massive increases in ovarian size, extravascular fluid shifts, and hemoconcentration that can result in shock and organ failure. Signaling by vasogenic molecules released from corpus lutae is thought to provoke increased epithelial membrane permeability.436,437 Unilateral and bilateral pleural effusions commonly occur during the full expression of the syndrome but also as isolated findings.438–441 Limited data exist regarding the PF profile, which is considered exudative.442 PF may contain high levels of cytokines.443 In most instances, OHSS is self-limited and spontaneous regression occurs although chest catheters may be required initially for draining large volumes of PF.444

ENVIRONMENTAL—ASBESTOS

ENVIRONMENTAL—ASBESTOS

Up to 3% of patients with an occupational exposure to asbestos will develop transient exudative pleural effusions,445–447 termed benign asbestos pleurisy.446,448 Asbestos exposure may underlie many undiagnosed exudative pleural effusions.447,449 The pathophysiology of benign asbestos pleurisy is uncertain, but asbestos fibers can provoke pleural inflammation both by direct toxicity to mesothelial cells and also by indirect effects through stimulating the release of growth factors and inflammatory cytokines from the lung.450 Mean latency time from first asbestos exposure to pleural effusions is 30 years but ranges from 1 to 58 years.451 Symptoms of dyspnea, chest pain, and/or fever develop in only 35% to 50% of patients.447,451 Pleural effusions range from small to large and present most often as unilateral effusions with equal side distribution or as bilateral effusions in 15%.446,451 PF appears hemorrhagic in 50% of patients, and 25% have increased numbers of eosinophils.449,451 The effusions almost always follow a benign course with spontaneous resolution within 1 to 10 months (median 3 months),451 but some effusions recur.447 Patients with heavy asbestos exposure may have residual pleural thickening,445–447,449,452 which may require decortication if lung restriction occurs.

LYMPHATICS AND LIPID-RELATED EFFUSIONS

LYMPHATICS AND LIPID-RELATED EFFUSIONS

Chylothorax

Chylothorax is defined by the presence of chyle in the pleural space,453 which denotes a leakage of lymphatic fluid from the thoracic duct or its tributaries. Chyle contains lipids in transit from the digestive tract to the venous circulation via the cisterna chyli near the junction of the left jugular and subclavian veins. Disruption of these lymphatic channels anywhere along their course can result in a pleural effusion. Lymphatic fluid also contains a high content of lymphocytes and immunoglobulins. A classification of chylothorax and listing of common causes are shown in Table 76-8.