Chapter 7 Nonatherosclerotic Vascular Disease

Vasospastic Disorders

Raynaud Syndrome

The prevalence of RS in the general population varies with climate and, probably, ethnic origin. In cool, damp climates such as the Pacific Northwest, Scandinavia, and Great Britain, the prevalence approaches 20% to 25%.1 It is not known whether the lower prevalence in warm, dry climates is due to a decreased occurrence of the syndrome or merely lack of patient complaints. RS occurs most frequently in young women.2 The median age of onset of RS is 14 years, with only 27% of cases beginning after age 40.3 Approximately one quarter of patients have a family history of RS in a first-degree relative.4

The mechanism of vasoconstriction in RS has been the subject of intense debate for more than a century. Raynaud speculated that sympathetic nervous system hyperactivity was responsible, a proposition disproved by Lewis in the 1920s when he demonstrated that blockade of digital nerve conduction did not prevent vasospasm.5 Lewis then proposed the theory of a local vascular fault, the nature of which remains undefined.

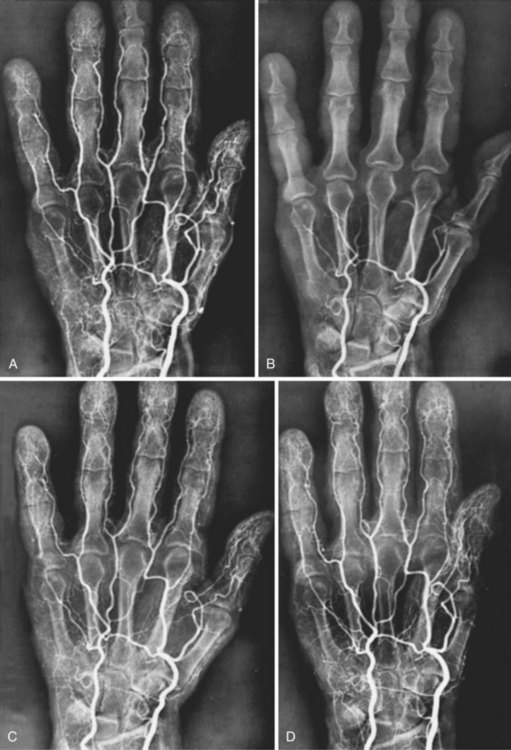

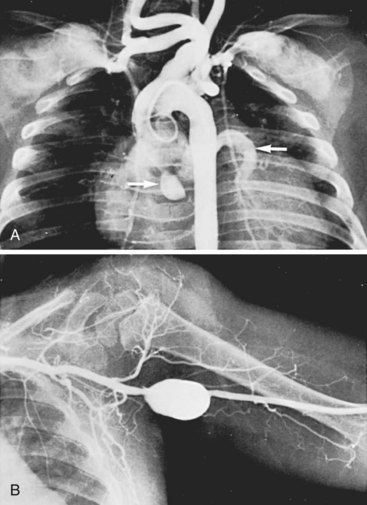

In recent years, the focus in RS pathophysiology has been on alterations in peripheral adrenoceptor activity. Increased finger blood flow was noted in patients following α-adrenergic blockade with drugs such as reserpine. Oral and intraarterial reserpine was the cornerstone of medical management of RS for several years, but it is no longer available.6 Angiograms of an RS patient before and after cold exposure and before and after intraarterial reserpine are shown in Figure 7-1.

Research in human vessel models demonstrated increased α2 receptor sensitivity to cold exposure.7 α2 Adrenoceptors appear to have a major role in the production of the symptoms of RS. α2 Receptors are present in a pure population on human platelets. Receptor levels in circulating cells appear to mirror tissue levels. Owing to the difficulty of obtaining digital arteries from human subjects, some researchers have measured levels of platelet α adrenoceptors, and an increased level of platelet α2 adrenoceptors in patients with RS has been demonstrated.8–10 Possible mechanisms of α2-adrenergic–induced RS include an elevation in the number of α2 receptor sites, receptor hypersensitivity, and alterations in the number of receptors exposed at any one time.11,12

The response of subcutaneous resistance vessels to acetylcholine has been shown to be diminished in patients with RS compared with controls, indicating a possible endothelium-dependent mechanism.13 The possible roles of the vasoactive peptides endothelin, a potent vasoconstrictor, and calcitonin gene-related peptide (CGRP), a vasodilator, have also been investigated. Serum endothelin levels increased significantly with cold exposure in patients with RS compared with controls.14,15 Depletion of endogenous CGRP may also contribute, because increased skin blood flow in response to CGRP infusion has been demonstrated in patients with RS compared with that in controls.16

Based on observations primarily at the Mayo Clinic 70 years ago by Allen and Brown,17 patients with Raynaud symptoms have traditionally been classified as having either Raynaud disease or Raynaud phenomenon, depending on the presence or absence of an associated systemic disease process. However, Raynaud phenomenon may precede the development of an associated disease by years. In addition, this system does not address the underlying palmar and digital artery disease that may be present. Patients with cold- or stress-induced digital ischemia are referred to as having RS, thus avoiding the semantic conflict of disease versus phenomenon.

In patients with obstructive RS, the mechanism of the obstructive process is variable. Patients with connective tissue disease typically have an autoimmune vasculitis, which is probably the mechanism underlying the widespread digital and palmar artery occlusions. Patients who work with vibrating tools have a similar process and frequently develop a peculiar fibrotic form of palmar and digital artery obstruction, presumably associated with injury from repeated shear stress.18 Hypercoagulable states may appear with digital artery occlusions, as can emboli from various sources, including valvular heart disease and subclavian, axillary, and ulnar aneurysms. Atherosclerosis involving the upper extremities is rarely seen in the younger age group, but is frequently observed in older patients, especially men.

A number of diseases have been recognized in association with RS, among which the connective tissue diseases are the most frequent; scleroderma is the most common. Associated diseases recognized in patients with RS are shown in Table 7-1.19 Estimates of the percentage of patients with RS and an associated disease range from 30% to 80%.1,20–24 It is important to note that the data from most series come from tertiary-care referral centers; therefore they might not reflect the actual incidence in the general population and may overestimate the actual prevalence of associated diseases. Clearly, most individuals with RS view the condition as a nuisance and do not seek medical advice.

TABLE 7-1 Associated Diseases in Raynaud Syndrome Patients: Oregon Health Sciences University Series

| Disease | No. of Patients |

|---|---|

| Autoimmune disease | 290 |

| Scleroderma | 95 |

| Undifferentiated connective tissue disease | 24 |

| Mixed connective tissue disease | 23 |

| Systemic lupus erythematosus | 17 |

| Sjögren’s syndrome | 16 |

| Rheumatoid arthritis | 9 |

| Positive serology | 106 |

| Other diseases or conditions | 300 |

| Atherosclerosis | 46 |

| Trauma | 44 |

| Hematologic abnormalities | 42 |

| Carpal tunnel syndrome | 35 |

| Frostbite | 32 |

| Buerger disease | 28 |

| Vibration | 21 |

| Hypersensitivity angiitis | 18 |

| Hypothyroidism | 13 |

| Cancer | 13 |

| Erythromelalgia | 8 |

| No associated disease | 498 |

| Total | 1088 |

From Landry G, Edwards JM, McLafferty RM, et al: Long-term outcome of Raynaud’s syndrome in a prospective analyzed cohort. J Vasc Surg 23:76–86, 1996.

A history suggestive of an associated connective tissue disease should be sought, including arthralgias, dysphagia, sclerodactyly, xerophthalmia, or xerostomia, as well as any prior history of large vessel occlusive disease, malignancy, hypothyroidism, frostbite, trauma, use of vibrating tools, and drug use. More than half of patients with carpal tunnel syndrome can have coexistent RS.25 The examiner should carefully evaluate the pulses and assess the digits for evidence of active or healed ulceration, sclerodactyly, telangiectasia, and calcinosis. The optimal serologic evaluation has not been defined. It is common to obtain a complete blood cell count, erythrocyte sedimentation rate, antinuclear antibody titer, and rheumatoid factor. Patients who exhibit sudden-onset digital ischemia should be evaluated for hypercoagulable states. Tests for specific connective tissue diseases are obtained based on clinical suspicion. Importantly, the physical examination in patients with RS is frequently normal, and the diagnosis relies on history and noninvasive tests.

Routine vascular laboratory testing consists of digital photoplethysmography and digital blood pressures. The digital photoplethysmographic recording provides qualitative information on the character of the arterial waveform.26 Normal digital blood pressure is within 30 mm Hg of brachial pressure. Patients with obstructive RS have blunted waveforms, whereas patients with vasospastic RS have either normal waveforms or a “peaked pulse.” The peaked pulse pattern, first described by Sumner and Strandness,27 appears to reflect increased vasospastic arterial resistance.

The utility of cold provocation testing remains controversial. Tests involving immersion of patients’ hands in ice water are not clinically useful because of low specificity and reproducibility.28,29 Of greater clinical utility is a digital hypothermic cold challenge test described by Nielson and Lassen.30 This test is performed with a liquid-perfused cuff placed on the proximal phalanx of the target finger. The cuff is inflated to suprasystolic pressure for 5 minutes while it is perfused with cold water. The pressure at which blood flow is detected on deflation of the cuff is recorded. A control finger on the same hand is tested at room temperature. The test is repeated at several temperatures, and the result is expressed as the percentage drop in finger systolic pressure with cooling. This test has an overall sensitivity and accuracy of approximately 90%.31

Duplex scanning does not appear to have a major role in the diagnosis of RS, although it can be used to search for proximal arterial obstructive or aneurysmal disease. Laser Doppler imaging is a promising new modality that quantifies digital microvascular blood flow and may have future diagnostic applications in RS.32,33 Angiography was used extensively in the past, particularly in the evaluation of patients with obstructive RS. Patients with an underlying systemic disease process and bilateral palmar and digital arterial obstructive disease documented by vascular laboratory testing do not require angiography to confirm digital artery occlusive disease. Patients with unilateral disease, particularly those who have only one or two digits of one arm involved, should be considered for angiography to determine both the presence of bilateral disease and the presence of any proximal arterial disease. Avoidance of triggering stimuli, such as cold or emotional stress, is the hallmark of conservative treatment.34 We advise all patients with RS to avoid tobacco use, although a multicenter epidemiologic study suggested that RS is not strongly influenced by tobacco consumption.35 Medications that have been associated with the causation of RS symptoms, such as ergot alkaloids and β-blockers, should be avoided if appropriate alternative therapies exist. More than 90% of patients with RS respond adequately to these simple conservative measures and require no additional treatment. The small number of patients who develop digital ulcers in association with obstructive RS can also be managed conservatively. A healing rate of 85% has been achieved with simple treatment consisting of soap and water scrubs, antibiotics as selected by culture, and conservative debridement.36 Calcium channel blockers are the most widely used pharmacologic agent for the treatment of RS. As a rule, patients with vasospastic RS respond more favorably to medical therapy than do those with occlusive RS. The dihydropyridine calcium channel blockers are most effective, and nifedipine has been the most studied, with a significant decrease in attack frequency and severity in numerous trials.37 Potential side effects include headache, ankle swelling, pruritus, and, rarely, severe fatigue. Other calcium channel blockers include nicardipine, amlodipine, and felodipine.38 Second-line medications with proven efficacy include α-blockers (prazosin),39 angiotensin II receptor blockers (losartan),40 serotonin reuptake inhibitors (fluoxetine),41 phosphodiesterase 5 inhibitors (sildenafil, tadalafil),42,43 and topical nitrates.44

Active research continues in the treatment of RS with the prostaglandins: PGE1, PGE2, and prostacyclin, (PGI2). Intravenous iloprost, a stable analog of PGI2, has been shown to be effective in the treatment of RS associated with systemic sclerosis.45 In placebo-controlled, double-blind studies, intravenous iloprost was associated with both decreased frequency of Raynaud episodes and increased frequency of ulcer healing.46 Several multicenter clinical trials have examined the efficacy of oral forms of iloprost. Although some groups have detected modest improvements in patients with RS, particularly if associated with systemic sclerosis,47 others have found no benefit when compared with placebo.48,49 Endothelin receptor antagonists (bosentan) have also shown benefit in preventing and treating digital ulcers,50 but has a high rate of liver toxicity and is approved by U.S. Food and Drug Administration only for treatment of pulmonary hypertension. Temperature biofeedback, in which patients are taught hand warming through behavioral techniques, was initially believed to reduce symptom frequency in patients with vasospastic RS.51 However, a randomized trial showed no improvement in symptoms after 1 year compared with a control technique.52 Transcutaneous electrical nerve stimulation, which has been described as causing vasodilatation, resulted in only mild increases in skin temperature; it caused no improvements in digital plethysmography or transcutaneous partial pressure of oxygen in test hands and had a negligible effect on symptoms.53 Acupuncture has also been suggested as a possible treatment alternative, with a significant reduction in frequency and severity of attacks.54

Several small case series have demonstrated decreased frequency of attacks and improved ulcer healing with chemical sympathectomy using an interdigital injection of botulinum toxin.55,56 Surgical cervicothoracic sympathectomy has not been shown to have a lasting benefit in most series, with recurrence rates as high as 82% at 16 months’ follow-up.57 In a large series of patients undergoing thoracoscopic sympathectomy, increased digital artery perfusion was maintained out to 5 years’ follow-up, although symptom recurrence occurred in 28% of patients.58 In contrast to upper extremity sympathectomy, excellent results have been achieved with lower extremity sympathectomy, with long-term symptomatic relief noted in more than 90% of patients undergoing this procedure.59 Lumbar sympathectomy remains a viable option in the rare patient with severely symptomatic lower extremity vasospasm, and it is amenable to minimally invasive laparoscopic techniques.60

Periarterial neurectomy is performed by removing the adventitia of the radial, ulnar, palmar, or common digital arteries. Several modifications of this technique have been published, generally characterized by increasing the length of adventitial stripping to facilitate more distal sympathectomy.61,62 Results have been mixed, with some series reporting improved quality of life and ulcer healing, although complication rates are as high as 37%63; therefore widespread use is generally discouraged.

A minority of patients with RS have an identifiable proximal cause of upper extremity arterial insufficiency demonstrated on angiogram. Patients with subclavian, axillary, or brachial artery obstruction from atherosclerosis, emboli, proximal arterial aneurysms, or other causes are appropriate surgical candidates and can expect excellent results from operative intervention. Reconstruction of the palmar arch and direct microvascular bypass of occluded segments of palmar and digital arteries have been successful in a small number of patients.64,65 Arteriovenous reversal at the wrist has been advocated as a method of providing retrograde arterial perfusion to ischemic hands for limb salvage.66 These procedures, however, are applicable to only a few carefully selected patients.

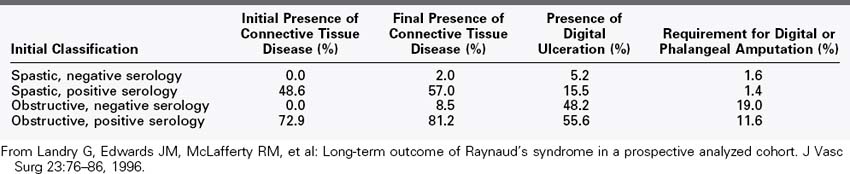

The long-term outcome of patients with RS is not known with certainty, although epidemiologic studies have shown that up to one third of patients with RS can experience symptom resolution over time.67 We reviewed our experience with more than 1000 RS patients followed for up to 23 years and found RS to be a relatively benign condition in the majority of patients.19 We divided the patients into four groups at presentation to determine whether this classification scheme provided prognostic information: vasospastic RS with negative serologies, vasospastic RS with positive serologies, obstructive RS with negative serologies, and obstructive RS with positive serologies. Patients with no evidence of an associated disease or arterial obstruction did extremely well, with minimal risk of severe finger ischemia or development of an associated disease; those with obstruction and positive serologies were most likely to develop worsening finger ischemia and ulceration. A summary is presented in Table 7-2. Patients without a diagnosable connective tissue disorder, but with one or more clinical signs or laboratory tests suggesting such a disease, are much more likely to receive a diagnosis of connective tissue disorder at a later date. Current estimates of progression range from 2% to 6% in patients with initially negative serologic tests to 30% to 75% in patients with positive serologic tests at presentation.1,22,23,68 Although fingertip debridement and occasional distal phalanx amputation are required to aid ulcer healing, we have performed major interphalangeal finger amputations in only 2 of the more than 1000 RS patients we have evaluated and treated.

Systemic Vasculitis

Vasculitis has a deceptively simple definition—inflammation, often with necrosis and occlusive changes of the blood vessels—but its clinical manifestations are diverse and complex.69 The term arteritis has been used to describe many of these syndromes, but vasculitis is a more precise term, because many of the entities involve veins as well as arteries. Vasculitis can be generalized or localized. Knowledge of this condition is incomplete, and the currently used classification systems are filled with exceptions and overlapping syndromes. The most useful classification system is based on the size of the vessels (small, medium, large) involved by the vasculitic process (Box 7-1).70 Medium and small vessel vasculitis is further subdivided by the presence or absence of antineutrophil cytoplasmic antibodies (ANCAs), a group of autoantibodies formed against enzymes found in primary granules of neutrophils. The most common ANCA-positive vasculitides include Wegener granulomatosis, microscopic polyangiitis, and Churg-Strauss syndrome, which are rarely encountered by vascular surgeons.71

Box 7-1

Vasculitides with Potential Vascular Surgical Importance

The cause and pathogenesis of most vasculitides are complex and are currently either unknown or incompletely understood. Earlier attempts to associate vasculitis with a single mechanism of immune complex-induced injury have not been substantiated in the majority of vasculitides.72 The basic pathologic mechanism of vasculitis implicates immune-mediated injury, which can include recognition of a vascular structure as antigen, deposition of immune complexes in a vessel wall with complement activation and injury, direct deposition of antigen in a vessel wall, or a delayed hypersensitivity reaction.

The majority of vasculitides are associated with a cellular immunoreaction involving the production of soluble mediators including cytokines, arachidonic acid metabolites, and fibrinolytic and coagulation by-products. The production of cytokines results in neutrophilic, eosinophilic, monocytic, and lymphocytic interactions at the inflammatory site. Endothelial cells express cell membrane receptors specific for many of these inflammatory cells. Binding of inflammatory cells to the endothelial cell triggers intracellular production of additional endothelial cytokines that affect the local inflammatory environment. Complement binding is thought to aid the attachment of leukocytes to endothelial cells. Platelet interactions with both intact and injured endothelium can contribute to the inflammatory process through activation of coagulation pathways and release of cytokines capable of stimulating and modifying immune responses.72,73

The vascular surgeon attends to the sequelae of vasculitic injury in these diseases. Thrombosis, aneurysm formation, hemorrhage, or arterial occlusion may all follow or accompany transmural damage created by inflammatory reactions on the vascular wall. An abbreviated list of the vasculitides that have potential significance to vascular surgeons is presented in Box 7-1 and is considered in this section.

Large Vessel Vasculitis

Giant Cell Arteritis Group

The two conditions included in the giant cell arteritis group are systemic giant cell, or temporal, arteritis and Takayasu disease. Although they have fairly distinctive clinical patterns (Box 7-2), the two entities likely represent different manifestations of the same disease process. The microscopic pathologic findings of the two conditions are similar, and it is often impossible to clearly categorize individual tissue sections as one or the other. Both conditions consist of localized periarteritis with inflammatory mononuclear infiltrates and giant cells, along with disruption and fragmentation of the elastic fibers of the arterial wall. The arterial inflammation begins and is most pronounced in the media. In both conditions, the intensity of the cellular infiltrate and the number of giant cells are variable. Histologically, giant cells are pathognomonic but not essential to make the diagnosis of giant cell arteritis.

Box 7-2

Clinical Patterns in Giant Cell Arteritis

| Temporal Arteritis | Takaysu’s Disease | |

|---|---|---|

| Age, sex | Elderly, white women | Young females |

| Pathology | Inflammatory cellular infiltrates Giant Cells | Same |

| Area of involvement | Usually branches of carotid; may involve any artery | Aortic arch and branches; pulmonary artery |

| Complications | Blindness | Hypertension, stroke |

| Response to steroids | Excellent | Unpredictable, unproved |

Both giant cell arteritis and Takayasu disease have a propensity for the insidious development of aneurysms of the thoracic and abdominal aorta, which may be accompanied by dissection. Both may be associated with slowly progressive occlusive lesions of the upper extremity, carotid, visceral, and renal arteries. The main differences between these two disease entities are the age and sex of afflicted individuals.74

Systemic Giant Cell Arteritis (Temporal Arteritis).

Systemic giant cell arteritis (GCA) is essentially limited to patients older than 50 years; it occurs twofold to sixfold more frequently in women as in men and is more prominent in whites. The annual incidence in white women older than 50 years is 15 to 25 cases per 100,000.75 Polymyalgia rheumatica, a clinical syndrome of aching and stiffness of the hip and shoulder girdle muscles lasting 4 weeks or longer and associated with an elevated erythrocyte sedimentation rate, is present in 50% to 75% of patients with temporal arteritis.76

GCA can involve any large artery of the body, although it has a propensity to affect branches of the carotid artery. The clinical history usually begins with a febrile myalgic process involving primarily the back, shoulder, and pelvic regions. Headache, malaise, anorexia, weight loss, and jaw claudication are common. The most characteristic complaint is severe pain along the course of the temporal artery, accompanied by tenderness and nodularity of the artery and overlying skin erythema. The involvement is frequently bilateral. Visual disturbances occur in more than 50% of patients. The mechanism of the visual alterations may be ischemic optic neuritis, retrobulbar neuritis, or occlusion of the central retinal artery. Unilateral blindness occurs in as many as 17% of patients with GCA, followed by contralateral, usually permanent, blindness in one third of these patients within 1 week.77 Amaurosis fugax is an important warning sign that precedes visual loss in 44% of patients.78

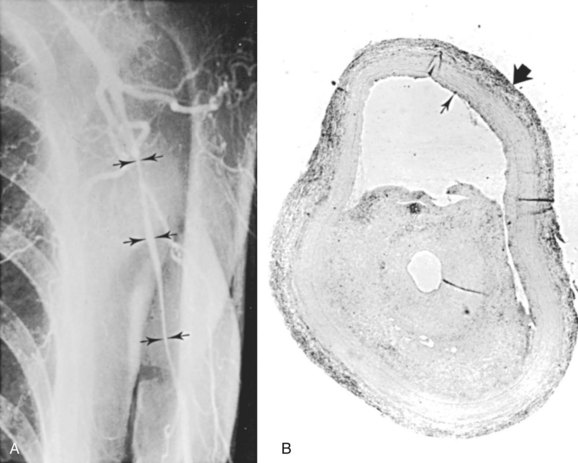

GCA is of concern to cardiac and vascular surgeons, because it can cause aneurysms or stenoses of the aorta or its main branches. Both true thoracic aortic aneurysms and dissecting aneurysms can occur. Patients with GCA have a 17-fold increased risk of thoracic aortic aneurysms and a 2.4-fold increased risk of abdominal aortic aneurysms compared with age-matched controls.79 Classic arteriographic findings of GCA include smooth, tapering stenoses of subclavian, axillary, and brachial arteries (Figure 7-2). Aortic involvement is best visualized with computed tomography (CT) or magnetic resonance angiography (MRA), in which aortic wall thickening is demonstrated.80 Klein and associates81 found that 14% of patients with GCA had evidence of symptomatic large artery involvement. Symptomatic subclavian-axillary occlusion is a frequent presenting symptom of GCA.82 Although rare, lower extremity involvement has also been described.83 Laboratory findings supporting a diagnosis of GCA include an elevated erythrocyte sedimentation rate. The diagnostic criteria of the American College of Rheumatology include an erythrocyte sedimentation rate of at least 50 mm/hour.84 However, up to 25% of patients with GCA have a normal sedimentation rate at the time of diagnosis,85 and this finding should not preclude treatment if clinical suspicion is high. C-reactive protein may be a more sensitive indicator of disease activity than the sedimentation rate.86

Temporal artery biopsy remains the gold standard of diagnosis in patients suspected of having GCA. Because of skip lesions, a specimen at least 2 cm long should be obtained. When possible, temporal artery biopsy should be performed before corticosteroid treatment; however, histologic evidence of arteritis may be found after up to 2 weeks of treatment.87 Bilateral sequential temporal artery biopsies are frequently performed if the results of unilateral biopsy are inconclusive, but in 97% of cases, the two specimens show the same findings.88 Characteristic findings on color-flow duplex scans have been described, typically a hypoechoic halo around the artery corresponding with associated periarterial inflammation, with a sensitivity of 75% and specificity of 83% compared with temporal artery biopsies.89

The importance of a precise and early diagnosis lies in the early initiation of steroid therapy. Prompt steroid therapy frequently results in restoration of pulses and prevention of lasting visual disturbances. Typical treatment consists of initial high-dose intravenous steroids followed by a gradual oral taper. Most patients require at least 1 year of treatment, although some require lifelong therapy.90,91 Although corticosteroids remain the cornerstone of medical therapy, cytotoxic agents (e.g., methotrexate), immunosuppressants (e.g., azathioprine, cyclosporin), and antitumor necrosis factor monoclonal antibody (infliximab) are used occasionally.92,93 However, trials of steroid-sparing drugs have had conflicting results. With the exception of those with aortic dissections, the life expectancy of patients with GCA is the same as that of the general population.94

Takayasu Disease.

Takayasu disease frequently affects the aorta and its major branches and, in contrast to GCA, the pulmonary artery. The majority of patients are Asian, about 85% are female, and the median age at onset is between 25 and 41 years.95 The disease has two recognized stages. The first stage is characterized by fever, myalgia, and anorexia in approximately two thirds of patients. In the second stage, these symptoms may be followed by multiple arterial occlusive symptoms, with manifestations dependent on disease location.

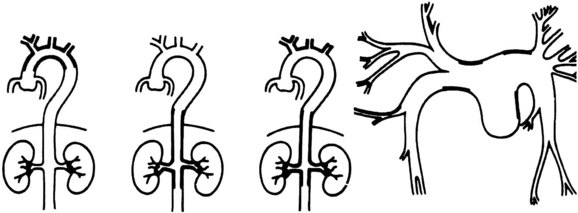

The cardiovascular areas of involvement have been characterized as types I, II, III, and IV and are shown in Figure 7-3. Type I is limited to involvement of the arch and arch vessels and occurs in 8.4% of patients. Type II involves the descending thoracic and abdominal aorta and accounts for 11.2% of cases. Type III involves the arch vessels and the abdominal aorta and its branches and accounts for 65.4% of cases. Type IV consists primarily of pulmonary artery involvement, with or without other vessels, and accounts for 15% of patients.96 Most of the lesions are stenotic, although localized aneurysms have been reported. Arteriography has traditionally been the imaging modality of choice.97 However, color-flow duplex scanning,98 CT,99 magnetic resonance imaging (MRI),100 and positron emission tomography scanning101 have emerged as important alternatives, providing information about both luminal and mural involvement in affected vessels.

Available information suggests that a conservative surgical approach is best for these patients. A poor long-term outcome is predicted by the presence of major complications (retinopathy, hypertension, aortic insufficiency, aneurysm formation) and a progressive disease course.102 Surgical intervention is generally reserved to treat symptomatic stenotic or, less commonly, aneurysmal lesions resulting from chronic Takayasu arteritis. Surgical intervention is best performed with the disease in a quiescent state. Restenosis rates in the presence of active disease are approximately 45%, compared with 12% restenosis rates with quiescent disease.103 Successful surgical management requires bypass graft implantation into disease-free arterial segments and continuation of corticosteroid therapy.104 Excellent long-term survival rates of up to 75% at 20 years have been reported in large operative series.105 Owing to its inflammatory nature, endarterectomy has resulted in early failure and is generally not recommended.

Percutaneous transluminal angioplasty and stenting has had mixed success, with high early success rates of up to 90%106; however, high rates of in-stent restenosis have been reported.107 In general, surgical intervention remains a more durable option.

Radiation-Induced Arterial Damage

Radiation given for the treatment of regional malignancy causes well-recognized changes in arteries within the irradiated field. The primary changes consist of intimal thickening and proliferation, medial hyalinization, proteoglycan deposition, and cellular infiltration of the adventitia. Normal endothelium has a slow rate of turnover, and following irradiation, endothelial cells do not proliferate. Pleomorphic endothelial cells can develop as a result of irradiation, with exposure of the basement membrane leading to thrombosis of small vessels.108 Postirradiation changes in large arteries often resemble atherosclerosis (Figure 7-4).

Of considerable importance is the tendency for arteries in an irradiated area to show stenosis years later, thought to be due to chronic oxidative stress with upregulation of matrix metalloproteinases, proinflammatory cytokines, smooth muscle cell proliferation and apoptosis, with downregulation of nitric oxide.109 There is an unusually high incidence of carotid artery stenosis in patients years after neck irradiation, along with an increased likelihood of stroke.110 The lesions vary from diffuse scarring to areas of typical atheromatous narrowing, with a preponderance of the latter. Patients who have had regional irradiation, especially of the cervical region, should have careful vascular follow-up, including noninvasive vascular laboratory examinations. Stenoses of the subclavian and axillary arteries have been demonstrated in patients undergoing radiation therapy for breast cancer and Hodgkin lymphoma, and aortoiliac involvement has been noted in patients undergoing abdominal or pelvic radiation therapy.

Vascular surgery on irradiated arteries can be performed using standard techniques. Prosthetic and autogenous bypass grafts, as well as endarterectomy, have all been performed satisfactorily.111 Prudence suggests avoidance of a prosthetic graft in a field in which infection may be expected, such as a radical neck dissection after irradiation, and autologous vein reconstruction is preferred. Late graft infections occurring 2 to 5 years after surgery have been described.112 The treatment of carotid artery stenosis in irradiated areas with percutaneous angioplasty and stenting has been reported, with excellent results,113,114 although rates of restenosis and reintervention are significantly higher than in nonirradiated arteries and historical surgical controls. Although data are limited, endovascular treatment of other arterial beds appears to be safe and effective in selected cases.115

Medium Vessel Vasculitis

Polyarteritis Nodosa

Polyarteritis nodosa (PAN) is a disseminated disease characterized by focal necrotizing lesions involving primarily medium-size muscular arteries. This is a rare disorder with a population of 2 to 16 per 1 million, a male-female preponderance of 2-4 : 1, and a peak incidence in the 40s.116 The clinical manifestations of PAN are varied. It can involve only one organ or multiple organs simultaneously or sequentially over time. The most frequent manifestations of PAN include a characteristic crescent-forming glomerulonephritis, polyarteritis, polymyositis, and abdominal pain. A cutaneous form also exists, presenting with subcutaneous nodules, livedo reticularis, and cutaneous ulcers.117

The essential pathologic feature of PAN is focal transmural arterial inflammatory necrosis. The process begins with medial destruction, followed by a sequential acute inflammatory response, fibroblastic proliferation, and endothelial damage. Immune complexes do not appear to be involved in the endothelial degeneration. The vascular injury is resolved by intimal proliferation, thrombosis, or aneurysm formation, all of which may culminate in luminal occlusion, with consequent organ ischemia and infarction.118

The erythrocyte sedimentation rate, C-reactive protein, and factor XIII–related protein, all nonspecific serologic markers of inflammation, are elevated in PAN. Positive hepatitis B serologies are common in adults with PAN.119 Mild anemia and leukocytosis are frequent. ANCAs have been detected in patients with systemic vasculitis, including PAN, Wegener granulomatosis, Churg-Strauss syndrome, temporal arteritis, and Kawasaki disease.120

The hallmark of PAN is the formation of multiple saccular aneurysms associated with inflammatory destruction of the media, with the most frequently involved organs being the kidney, heart, liver, and gastrointestinal tract. Rupture of intraabdominal PAN aneurysms has been well described and may represent a surgical emergency.121 Coil embolization of ruptured visceral aneurysms in PAN has also been described and represents an alternative to surgical intervention.122 Curiously, these aneurysms have been documented to regress on occasion after vigorous steroid and cyclophosphamide therapy, which should be recommended for all asymptomatic visceral aneurysms.123 An arteriogram of a patient with PAN showing the typical visceral and renal artery aneurysms is shown in Figure 7-5. Visceral PAN lesions can also lead to visceral artery narrowing incident to the inflammatory process, which can progress to occlusion. The visceral ischemia can manifest as cholecystitis, appendicitis, enteric perforation, gastrointestinal hemorrhage, or ischemic stricture formation with bowel obstruction.124

The routine use of steroid therapy has improved 5-year survival from 15% to the current 50% to 80%.125 Cyclophosphamide can be added to the steroid regimen in acute, severe cases.126 It has been suggested that prognosis can be determined by the absence or presence of creatinemia, proteinuria, cardiomyopathy, and gastrointestinal or central nervous system involvement at the time of presentation. Five-year mortality with zero, one, or two or more of these signs was 12%, 26%, and 46%, respectively.127 During the acute phase of PAN, renal and gastrointestinal lesions account for the majority of deaths, whereas cardiovascular and cerebral events account for mortality in chronic cases.

Kawasaki Disease

In the 1960s, an unusual febrile exanthematous illness swept Japan. Kawasaki observed 50 cases in the Department of Pediatrics at the Japan Red Cross Medical Center and termed the disease the mucocutaneous lymph node syndrome.128 Over the next decade, the spread of the disease was noted worldwide, and it became known as Kawasaki disease. The disease is not limited to those of Asian descent and occurs in all ethnic groups, although children of Japanese or mixed Japanese ancestry appear to be most susceptible. The annual incidence in Japan is 140 cases per 100,000 children younger than 5 years,129 compared with the incidence in the United States of approximately 17 cases per 100,000 children.130 The vasculitis associated with Kawasaki disease has a propensity to affect the coronary arteries, making it the most common cause of acquired heart disease in children in the developed world.131

As the disease has become better known, strict clinical criteria have evolved for diagnosis: (1) high fever present for 5 days or more; (2) bilateral congestion of ocular conjunctiva; (3) changes in the mucous membranes of the oral cavity, including erythema, dryness, and fissuring of the lips or diffuse reddening of the oropharyngeal mucosa; (4) changes in the peripheral portions of the extremities, including reddening and induration of the hands and feet and periungual desquamation; (5) polymorphous exanthem; and (6) acute nonsuppurative swelling of the cervical lymph nodes. The presence of a prolonged high fever and any four of the five remaining criteria, in the absence of concurrent evidence of bacterial or viral infection, establishes the diagnosis.132

Kawasaki disease has a unimodal peak incidence at 1 year of age; it has not been described in neonates and is rarely observed for the first time in those older than 5 years. The acute symptoms can persist for 7 to 14 days before improvement occurs as the fever subsides. Notable laboratory features include elevation of the erythrocyte sedimentation rate and C-reactive protein, thrombocythemia, and elevated levels of von Willebrand factor.133

The etiology of Kawasaki disease is likely multifactorial. An infectious cause has long been assumed, given the self-limited nature of the disease, its seasonal incidence, and geographic outbreaks. However, no single infectious agent has been demonstrated. An immunologic defect has also been postulated, as there appears to be an altered immunoregulatory state in these patients, with decreased numbers of T cells and an increased proportion of activated helper T4 cells. Genetic susceptibility also appears to have a role pathogenesis.134 The most serious disease manifestation is coronary arteritis, which is likely present in all children with this disease. The spectrum of documented coronary artery pathologic changes consists of active arteritis, thrombosis, calcification, and stenosis, although the distinguishing feature of Kawasaki disease is the formation of diffuse fusiform and saccular coronary artery aneurysms.

Routine echocardiography in patients with Kawasaki disease has demonstrated coronary artery dilatation or aneurysms in 25% to 50%, with the aneurysms typically appearing in the second week of illness and reaching a maximum size from the third to eighth week after the onset of fever.135 Echocardiography may show dilatation of the right, left, or anterior descending coronary arteries, while the circumflex coronary artery is rarely involved.136

Serial arteriographic studies have shown a considerable capacity for all types of coronary arterial lesions to evolve. The aneurysms may regress, leaving a patent arterial lumen, or the arterial segment may become stenotic. Most stenotic lesions regress, with maintenance of a patent lumen, but a few progress to occlusion. Stenotic lesions demonstrated by coronary angiography are most frequently seen in the left anterior descending artery. Patients older than 2 years with fever lasting longer than 14 days and pericardial effusion and those not treated with anticoagulant agents appear to have a higher incidence of aneurysm formation.135 Patients treated with immune globulin have shown a decreased incidence of aneurysm formation. New coronary arterial lesions occur infrequently after 2 weeks. Regression of the lesions occurs over a 2-month period, although some lesions remain unchanged for more than 1 year before regression.137

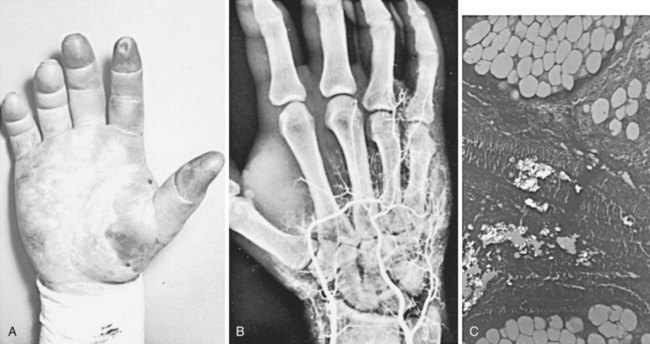

Systemic arteritis also occurs in Kawasaki disease, with iliac arteritis as prevalent as coronary arteritis. Aneurysm formation is far less frequent in the systemic arteries than in the coronary arteries, with one report identifying systemic arterial aneurysms (axillary and iliac) in 3.3% of 662 patients with Kawasaki disease and coronary artery aneurysms.138 The healing process in the systemic arterial lesions can lead to focal arterial stenosis or aneurysm formation, just as in the coronary arteries. The coexistence of peripheral arterial involvement (subclavian and axillary arteries) and coronary artery aneurysms is shown in Figure 7-6.

Thrombosis of coronary artery aneurysms is the overwhelming cause of death in the early stages of Kawasaki disease, causing acute myocardial infarction or arrhythmia. Coronary aneurysm rupture has also been described. With the initiation of aspirin and immune globulin therapy in the acute phase, the mortality from Kawasaki disease has decreased to 1.1%, and among patients with no cardiac sequelae does not differ from the general population.139 Intravenous gamma globulin is typically given as a single-infusion high dose of 2 g/kg. Aspirin is given orally at a dose of 80 mg/kg per day until the child is afebrile, then continued in low-dose form (3 to 5 mg/kg per day) for an additional 6 to 8 weeks.131 Approximately 10% to 15% of patients are refractory to standard therapy,140 and corticosteroids or other immunosuppressant agents (e.g., infliximab, cyclosporin) are considered in these patients.141

Coronary artery bypass grafting was first used in Kawasaki disease in 1976.142 The first procedure used the saphenous vein as a conduit; however, concerns over its potential to grow with the child have been raised. This concern led to the use of the internal mammary artery (unilateral or bilateral)143 and the right gastroepiploic artery144 for coronary revascularization in patients with Kawasaki disease. Five- and 15-year patency rates of internal mammary grafts are 91% in children older than 12 years of age, but only 73% and 65%, respectively, in patients younger than 12.145 Percutaneous angioplasty of anastomotic lesions, however, has improved 10-year patency rates in this group to 94%.146 Primary catheter based interventions, such as stent implantation147 and coronary rotational ablation,148 have also had excellent results in selected cases of focal coronary artery stenosis. Cardiac transplantation for severe ischemic heart disease as a sequela of Kawasaki disease is considered in patients who are not candidates for revascularization because of distal coronary stenosis or aneurysms and those with severe irreversible myocardial dysfunction.149

Aneurysms of the abdominal aorta and iliac, axillary, brachial, mesenteric, and renal arteries have been observed as late sequelae of systemic vasculitis. When these lesions become symptomatic from occlusion, expansion, or embolization, most surgeons proceed with standard repair techniques using interposition grafting. Although experience is limited, surgical repair of the aneurysms has been accomplished safely.150

Drug Abuse Arteritis

Intravenous drug abuse, particularly the use of methamphetamines or cocaine, is associated with a panarteritis similar in presentation and appearance to PAN,151 with combinations of renal failure, central nervous system dysfunction, and localized intestinal necrosis and perforation. Isolated cerebral angiitis has also been reported in the setting of methamphetamine and cocaine abuse.152,153 No medical therapy has proved effective for this condition. Necrotizing renal vasculitis secondary to oral methamphetamines (“ecstasy”) has also been described.154

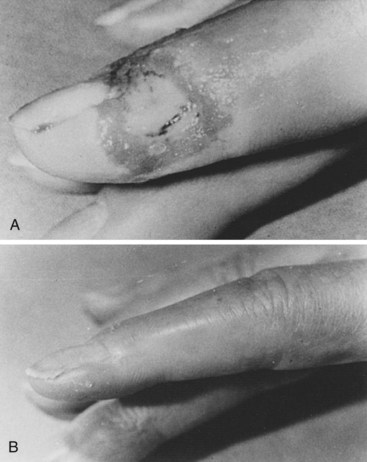

A second type of arterial obstruction has been reported in drug abuse patients following the accidental intraarterial injection of drugs during attempted intravenous injection. The drugs most commonly involved are parenteral barbiturates, in which case arterial injury and thrombosis appear to result from chemical damage, perhaps related to the low pH of the injectant.155 Another pattern of arterial damage results from the accidental injection of drug preparations intended for oral use. The practice of dissolving tablets in water for intravenous injection is enormously harmful because of the large number of substances (e.g., silica, tragacanth) in tablets. When this material is accidentally injected intraarterially, significant distal ischemia can result from obstruction of the small arteries by the inert materials (Figure 7-7).156

No convincing evidence has demonstrated the value of any specific treatment in these patients. A number of therapeutic efforts have been tried, including anticoagulation, regional sympathetic block, and the administration of vasodilators, without proof of efficacy. The outcome appears to be determined at the time of injection by the quantity and concentration of injectant reaching the distal arterial bed. Nonetheless, heparin anticoagulation is favored if the patient is seen acutely and has no contraindications to this treatment. Compartment syndrome requiring fasciotomy is an infrequent but reported sequela.157

Behçet Disease

In 1937, Behçet described three patients with iritis and associated oral and genital mucocutaneous ulcerations, an association subsequently termed Behçet disease.158 More than half of these patients have joint involvement. The underlying pathologic lesion is a vasculitis, which results in both venous thromboses and specific arterial lesions. Venous thrombosis is the most frequent vascular disorder in Behçet disease, representing approximately 70% of vascular lesions and affecting up to one third of patients.159 Arterial lesions are distinctly less frequent, occurring in 1% to 7% of patients, and include occlusive and aneurysmal disease.159 This systemic disease largely affects individuals from the Mediterranean area and East Asia and is more common in men.

The pathogenesis of vascular damage in Behçet disease appears to be an immune-mediated destructive process. A humorally mediated cause has been suggested by the identification of enhanced neutrophil activity and circulating immune complexes in affected patients.160 Specific T cell subsets have also been identified in high concentrations at the sites of vascular involvement, indicating a cellular-mediated process.161 Activation of complement within the vessel wall can lead to destruction of the media and subsequent aneurysm formation. Vasa vasorum occlusion can then lead to transmural necrosis of the large muscular arterial walls, with perforation and pseudoaneurysm formation and injury to adjacent tissues.162

Behçet disease may have a genetic component, because there is an increased incidence of the HLA-B51 allele among patients with the disease, with resultant abnormalities in tumor necrosis factor (TNF)-α expression.163 Both viral and bacterial causes have been proposed, although definitive evidence is lacking.164

Large artery involvement is an uncommon but serious complication of Behçet disease. Arterial aneurysms, although distinctly less common than the mucocutaneous, ophthalmic, or arthritic lesions, are the most frequent cause of death in patients with Behçet disease.165 Aneurysms have been described in numerous arteries, including the carotid, popliteal, femoral, iliac, pulmonary, and subclavian, but the aorta is the most frequent site of aneurysm formation in this disease.159 Curiously, the aneurysms frequently appear phlegmonous, suggesting acute bacterial infection, although cultures are invariably negative. The arterial aneurysms are frequently multiple and may be metachronous. Unfortunately, interposition bypass grafts have a high incidence of thrombosis, in addition to the propensity to develop anastomotic pseudoaneurysms, which tend to occur within the first 18 months in up to 13% of cases.166 Owing to the recognized difficulties of surgical aneurysm repair in Behçet disease, endovascular repair is emerging as the treatment of choice. The focal, saccular nature of these lesions makes them ideally suited to endovascular treatment. Excellent patency rates of endovascular treatment have been reported, but the fragile nature of the arteries puts patients at risk for pseudoaneurysm formation at seal zones, and aggressive stent oversizing is discouraged. Long-term immunosuppressive therapy is recommended after endovascular repair to limit pseudoaneurysm formation.167

Venous involvement is prominent, and lower extremity superficial or deep vein thrombosis occurs in 12% to 34% of patients, frequently alone or in association with arterial disease.159 Thrombosis of the superior or inferior vena cava or of intracerebral veins occurs less frequently but can be fatal. Lifelong anticoagulation is recommended in patients with Behçet disease who develop venous thrombosis, but the role of prophylactic anticoagulation is uncertain.

Immunosuppressive agents, including azathioprine, corticosteroids, TNF-α antagonists (infliximab) and interferon-α, have been used with some success for nonarterial symptoms.168 Although corticosteroids may prevent blindness and limit discomfort associated with the mucocutaneous disease, they do not appear to alter the progression or course of the underlying vascular disease. Currently, no uniformly satisfactory therapy exists for Behçet disease; however, early diagnosis and meticulous reconstructive management of identified arterial aneurysms have provided long-term limb salvage in some patients, despite the well-recognized propensity for arterial graft complications.169 Vigilant follow-up is required once large artery disease is recognized.

Cogan Syndrome

Cogan syndrome is a rare condition consisting of interstitial keratitis and vestibuloauditory symptoms. It is a disease primarily of young adults, with the mean age of onset in the third decade. It is occasionally associated with a systemic vasculitis similar to PAN. Aortitis with subsequent development of clinically significant aortic insufficiency occurs in 10% of patients with Cogan syndrome.170 Mesenteric vasculitis and thoracoabdominal aneurysms have also been described in association with Cogan syndrome.171,172

Daily administration of high-dose corticosteroids has been successful in reversing the visual and auditory components of Cogan syndrome, although deafness may be irreversible. The response of the aortitic component to steroids used singly or in combination with cyclosporine is less well established.173 Surgical therapy, including aortic valve replacement, mesenteric revascularization, and thoracoabdominal aortic aneurysm repair, is occasionally indicated and can be performed safely.

Vasculitis Associated with Malignancy

Vasculitis associated with malignancy is infrequent. A strong association has been made between a systemic necrotizing vasculitis resembling PAN and hairy cell leukemia. The vasculitis in this situation presents after the diagnosis of leukemia and is indistinguishable from classic PAN. An immune-mediated mechanism is postulated. More frequently, vasculitides involving small vessels have been described in association with lymphoproliferative disorders. These have primarily cutaneous manifestations and minimal visceral involvement and are often referred to as paraneoplastic vasculitides.174

Vasculitis associated with solid tumors is rare, but resolution with tumor excision has been reported.175 RS has been reported in association with carcinoma and lymphoproliferative malignancies. These cases were characterized by cold-induced ischemia, which frequently led to digital artery occlusion and ischemic ulcerations. The symptoms of finger ischemia preceded the diagnosis of malignancy, and several of these patients experienced marked improvement of their hand lesions after removal of the tumor.

Small Vessel Vasculitis

Hypersensitivity Vasculitis Group

The entities in the hypersensitivity vasculitis group include classic hypersensitivity vasculitis, mixed cryoglobulinemic vasculitis, and Henoch-Schönlein purpura. These conditions appear to result from antigen exposure followed by antigen-antibody immune complex deposition in small arteries and arterial damage. Hypersensitivity vasculitis usually has prominent skin involvement. In some conditions, a drug, an environmental chemical, or the hepatitis B virus may be implicated as the inciting antigen, but no causative agent is identified in more than half of cases. Henoch-Schönlein purpura is a self-limiting disease that occurs primarily in children and affects the skin, gastrointestinal tract, and kidneys. The disease course and findings are similar in cryoglobulinemic vasculitis, which may be associated with a hematologic malignancy or hepatitis B or C infection.176

The clinical syndromes typically associated with this group of diseases include skin rash, fever, and evidence of organ dysfunction, none of which specifically concerns vascular surgeons. It is clear, however, that some of these syndromes can manifest with arteritic involvement substantially limited to the hands and fingers. In these patients, the clinical picture is typically that of severe and widespread palmar and digital arterial occlusions and digital ischemia. The vasculitis can be treated with steroids, with the occasional use of immunosuppressive agents or plasmapheresis. The treatment of hand lesions can otherwise follow the approach outlined later in this chapter for Buerger disease.177

Vasculitis of Connective Tissue Diseases

The connective tissue diseases often are complicated by vasculitis. These diseases have associated immunologic abnormalities, and the occurrence of vasculitis in these patients likely results from immune-mediated damage, as described for other vasculitides.178 Vasculitis frequently accompanies scleroderma, rheumatoid arthritis, and systemic lupus erythematosus.

Scleroderma is the most frequent connective tissue disease recognized in our patients with RS, as well as those with digital ulceration (Figure 7-8).19 Approximately 80% to 97% of patients with scleroderma have symptoms of RS. In our experience, the RS usually begins as vasospastic and progresses to the obstructive type.

The vasculitis associated with rheumatoid arthritis involves primarily small arteries with a predilection for vasa nervorum and the digital arteries. Intimal proliferation, medial necrosis, and progression to fibrosis with vessel occlusion occur. Symptoms of mononeuritis multiplex are common following involvement of small arteries. Cutaneous lesions are often present and include digital ulcers, nail fold infarcts, and palpable purpura.179 Rarely, there is coronary, mesenteric, or cerebral artery involvement. Patients with rheumatoid arthritis who have positive ANCAs or higher titers of rheumatoid factor have a more aggressive disease course with a more frequent incidence of rheumatoid vasculitis.180,181 The presence of vasculitis portends a poor prognosis for patients with rheumatoid arthritis.

The vasculitis of systemic lupus erythematosus is believed to be due to deposition of immune complexes.182 The most frequent clinical vascular problem in lupus is RS, which can affect 80% of patients. Other vasculitic manifestations include palpable purpura and mononeuritis multiplex. Thrombotic disorders of the arterial and venous system occur in patients with lupus and appear to be related to the lupus anticoagulant, not vasculitis. IgA anti–double-stranded DNA antibodies and anti–endothelial cell antibodies are markers of more virulent vasculitic involvement.183 In addition to small vessel vasculitis, patients with systemic lupus erythematosus are clearly prone to premature large vessel atherosclerosis.184

Management of the vasculitides associated with the connective tissue diseases consists primarily of steroid therapy.182 Steroids appear to have little or no role in the treatment of the occlusive vascular lesions of scleroderma. Immunosuppressive therapy with cyclophosphamide has also been shown to have modest benefit in selected patients.185 The treatment of RS associated with lupus or scleroderma is as described earlier.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree