CHAPTER 39 Neoadjuvant and Adjuvant Therapy for Esophageal Cancer

Esophageal cancer is the sixth most common malignant neoplasm in the world. Historically, squamous cell carcinoma of the esophagus has been prevalent in patients with heavy alcohol and smoking abuse. During the past 20 years, adenocarcinoma of the distal esophagus and the gastroesophageal junction has increased in incidence about 10- to 20-fold in North America and Europe, replacing squamous cell carcinoma as the most common esophageal malignant neoplasm.1 Chronic gastroesophageal reflux disease, Barrett’s dysplasia, obesity, and smoking have been shown to be risk factors associated with esophageal adenocarcinoma.

STAGING MODALITIES

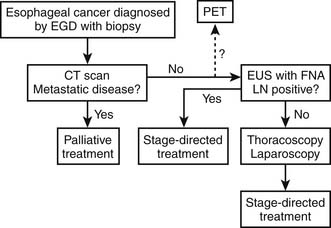

CT scan of the thorax and abdomen should be performed to stage the tumor, lymph node metastases, and distant metastases.2 Whereas CT is highly effective in the assessment of mediastinal esophageal carcinomas, it is less helpful in the staging of cervical or gastroesophageal junction carcinomas. Metastasis to celiac lymph nodes occurs most frequently with distal esophageal neoplasms (75%) and is present in nearly one third of patients with tumors of the proximal esophagus. Absence of fat planes is most often observed where the esophagus is in contact with the aorta, trachea, left main-stem bronchus, and left atrium. CT is very accurate in determining the presence of liver and adrenal gland metastasis.

EUS, one of the newer modalities for staging of esophageal cancer, uses the technologies of flexible endoscopy and ultrasonic imaging.3 By virtue of its ability to depict the various histologic layers of the esophageal wall and periesophageal tissues, EUS has proved useful in staging of esophageal cancer. EUS seems to be more accurate than CT in the diagnosis of very early or advanced stage of disease. Lymph nodes at a distance of more than 2 cm from the esophageal lumen cannot be imaged because of the very limited penetration depth of ultrasound. Tumor invasion into the tracheobronchial system should be further evaluated by bronchoscopy with transbronchial fine-needle aspiration (FNA) for confirmation of the diagnosis.

PET has been used to detect and to stage esophageal cancer. Block and coworkers4 compared CT and PET in staging of esophageal cancer. Among 58 patients, the uptake of fluorodeoxyglucose was increased at the site of the primary tumor in 56 patients. PET identified metastatic disease in 17 patients, whereas CT detected metastases in only five. Pathologic lymph node metastases were found in 21 patients. These nodes were detected by PET in 11 patients and by CT in six. For CT and PET together, the accuracy is nearly 92%. Luketich and associates5 found that for distant metastases, the sensitivity, specificity, and accuracy of PET were 88%, 93%, and 91%, respectively. For local-regional nodal metastases, the sensitivity, specificity, and accuracy were 45%, 100%, and 48%, respectively, suggesting that small local-regional nodal metastases cannot be identified by current PET technology. Recently, there has been additional interest in the utility of PET after neoadjuvant therapy as a means of predicting response to therapy. The predictive values for predicting microscopic residual disease remain wanting at present.

The use of EUS-guided FNA was reported in the diagnosis of esophageal cancer recurrence after distal esophageal resection and as a way of identifying and confirming mediastinal lymph node involvement, which is often crucial in planning the strategy of treatment, particularly before surgery. This advance has resulted in a change of our use of thoracoscopic and laparoscopic staging in esophageal cancer. EUS-FNA is currently able to achieve accurate lymph node staging in approximately 75% of patients (Fig. 39-1).

Many surgical studies show significant stratification of survival after resection of esophageal cancer based on accurate pathologic staging. Preoperative minimally invasive surgical staging in esophageal cancer may solve this problem just as the successful use of mediastinoscopy did in preoperative staging for lung cancer. Murray and associates6 first reported their experience with minimally invasive surgical staging for esophageal cancer in 1977. With use of mediastinoscopy and mini-laparotomy, seven patients had positive lymph nodes by mediastinoscopy and 16 had celiac lymph nodes identified. Dagnini and colleagues7 did routine laparoscopy in 369 patients with esophageal cancer and noted intra-abdominal metastases in 14% and celiac lymph node metastases in 9.7%.

With advances in thoracoscopic and laparoscopic techniques, thoracoscopy and laparoscopy have been used for staging of esophageal cancer. Successful combined thoracoscopy and laparoscopy for staging of disease in the chest and abdomen was evaluated in a follow-up series from three institutions of the Cancer and Leukemia Group B (CALGB) with an accuracy of more than 90%.8 A more recent report of 65 patients showed a 94% accuracy with laparoscopy and 91% accuracy with thoracoscopy in esophageal cancer staging. This study also demonstrated that clinical stage evaluation based on noninvasive diagnostic methods including CT, MRI, and EUS may be used to guide surgeons to focus on the suspicious areas for the highest-yield biopsy targets in thoracoscopic and laparoscopic staging.9 The main advantage of the thoracoscopic and laparoscopic staging procedure is that it provides greater accuracy in evaluation of regional and celiac lymph nodes. Such information is important in stratification of patients and selection of therapy, especially in the setting of new treatment protocols. Furthermore, the histologic status of mediastinal and abdominal lymph nodes is critical for the design of the field for irradiation. It allows dose delivery to be maximized to areas of known disease while minimizing dose to surrounding sensitive, normal tissue.10

MULTIMODALITY THERAPY APPROACHES TO SURGICAL MANAGEMENT

Neoadjuvant Radiotherapy

Preoperative radiation therapy is designed to reduce the tumor size and risk of tumor spread during surgical manipulation. Five published randomized trials compared neoadjuvant radiation followed by surgery versus surgery alone. None of the trials demonstrated survival benefit with preoperative radiation with the exception of the study by Nygaard and coworkers.11 The study by Nygaard has been widely criticized for using different doses and fractionation schedules and cross-analysis of the results from four different treatment groups. A meta-analysis from the Esophageal Cancer Collaborative Group concluded that survival is not improved with neoadjuvant radiotherapy and should not be recommended for patients for whom surgical resection is indicated.

Neoadjuvant Chemotherapy

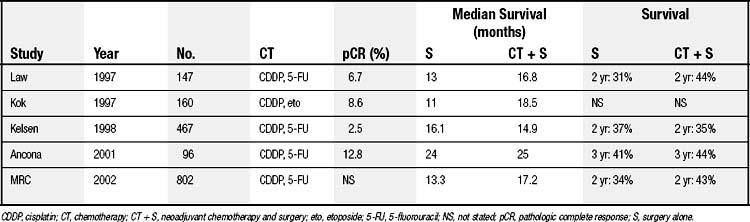

Several randomized prospective trials comparing neoadjuvant chemotherapy plus surgery with surgical resection alone have been published with mixed results (Table 39-1). The two largest trials were conducted in the United States and United Kingdom by the multicenter North American Intergroup (INT 0113) and the U.K. Medical Research Council Group (MRC OE02), respectively. The U.S. Intergroup randomized 467 patients with resectable esophageal adenocarcinoma (54%) and squamous cell carcinoma (46%). The study compared three cycles of neoadjuvant cisplatin and 5-fluorouracil followed by surgery and additional chemotherapy (cisplatin and 5-fluorouracil) with surgery alone. The results reported by Kelsen and associates12 showed that 2-year survival rates were 35% and 37% without a statistically significant difference in the overall survival between the two treatment groups. The MRC group randomized 802 patients with resectable esophageal adenocarcinoma (67%) and squamous cell carcinoma (33%) to two cycles of cisplatin and 5-fluorouracil plus surgery and surgery alone. An intent-to-treat analysis indicated that patients who received preoperative chemotherapy had a significant median (17.2 months versus 13.3 months) and 2-year (43% versus 34%) improvement in the survival rate.13 Although the neoadjuvant chemotherapy arm had a survival advantage, the survival data for 3 and 5 years are not yet available. It is unclear why the survival rate in the chemotherapy arm from this study is different from that of the U.S. Intergroup trial; further details from the U.K. MRC trial are worth reviewing. In the United States, preoperative chemotherapy is considered investigational and not the standard of care in management of esophageal cancer.

Table 39–1 Randomized Trials of Neoadjuvant Chemotherapy Versus Surgery Alone in Resectable Esophageal Carcinoma

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree