6

CHAPTER

![]()

Necrotizing Noninfectious Diseases

This chapter reviews diseases characterized by parenchymal necrosis associated with a cellular tissue reaction in the absence of an infectious etiology. Contrasting histologic and clinical features are summarized in Tables 6.1 and 6.2. Pulmonary infarcts are not included because they lack a significant tissue reaction; they are discussed in Chapter 12. Necrotizing infections are discussed in Chapters 7 and 8.

TOPICS

Granulomatosis With Polyangiitis (GPA; Formerly Wegener Granulomatosis)

Granulomatosis With Polyangiitis (GPA; Formerly Wegener Granulomatosis)

Eosinophilic Granulomatosis With Polyangiitis (EGPA; Formerly Churg–Strauss Syndrome (CSS)/Allergic Angiitis and Granulomatosis)

Eosinophilic Granulomatosis With Polyangiitis (EGPA; Formerly Churg–Strauss Syndrome (CSS)/Allergic Angiitis and Granulomatosis)

Necrotizing Sarcoid Granulomatosis (NSG)

Necrotizing Sarcoid Granulomatosis (NSG)

Bronchocentric Granulomatosis (BCG)

Bronchocentric Granulomatosis (BCG)

Rheumatoid Nodule

Rheumatoid Nodule

Lymphomatoid Granulomatosis (LYG)

Lymphomatoid Granulomatosis (LYG)

GRANULOMATOSIS WITH POLYANGIITIS (GPA)

The designation granulomatosis with polyangiitis (GPA) replaces the more familiar name, Wegener granulomatosis (WG), for a systemic vasculitic syndrome that most commonly involves lung, upper respiratory tract, and kidney. The name change was proposed because of Wegener’s alleged involvement with Nazi atrocities during the 1930s.

The histologic features of GPA are variable and can be divided into classic GPA, bronchiolitis obliterans–organizing pneumonia (BOOP)-like GPA, and the hemorrhage and capillaritis variant of GPA. In all cases, identification of a necrotizing vasculitis is necessary for histologic diagnosis, and, except for the hemorrhage and capillaritis variant, granulomatous inflammation is also present.

Histologic Features

Classic GPA

Necrotizing, usually suppurative, granulomatous inflammation with irregular, “dirty” necrosis and darkly staining multinucleated giant cells

Necrotizing, usually suppurative, granulomatous inflammation with irregular, “dirty” necrosis and darkly staining multinucleated giant cells

Palisading granulomas and random collagen necrosis

Palisading granulomas and random collagen necrosis

Necrotizing vasculitis

Necrotizing vasculitis

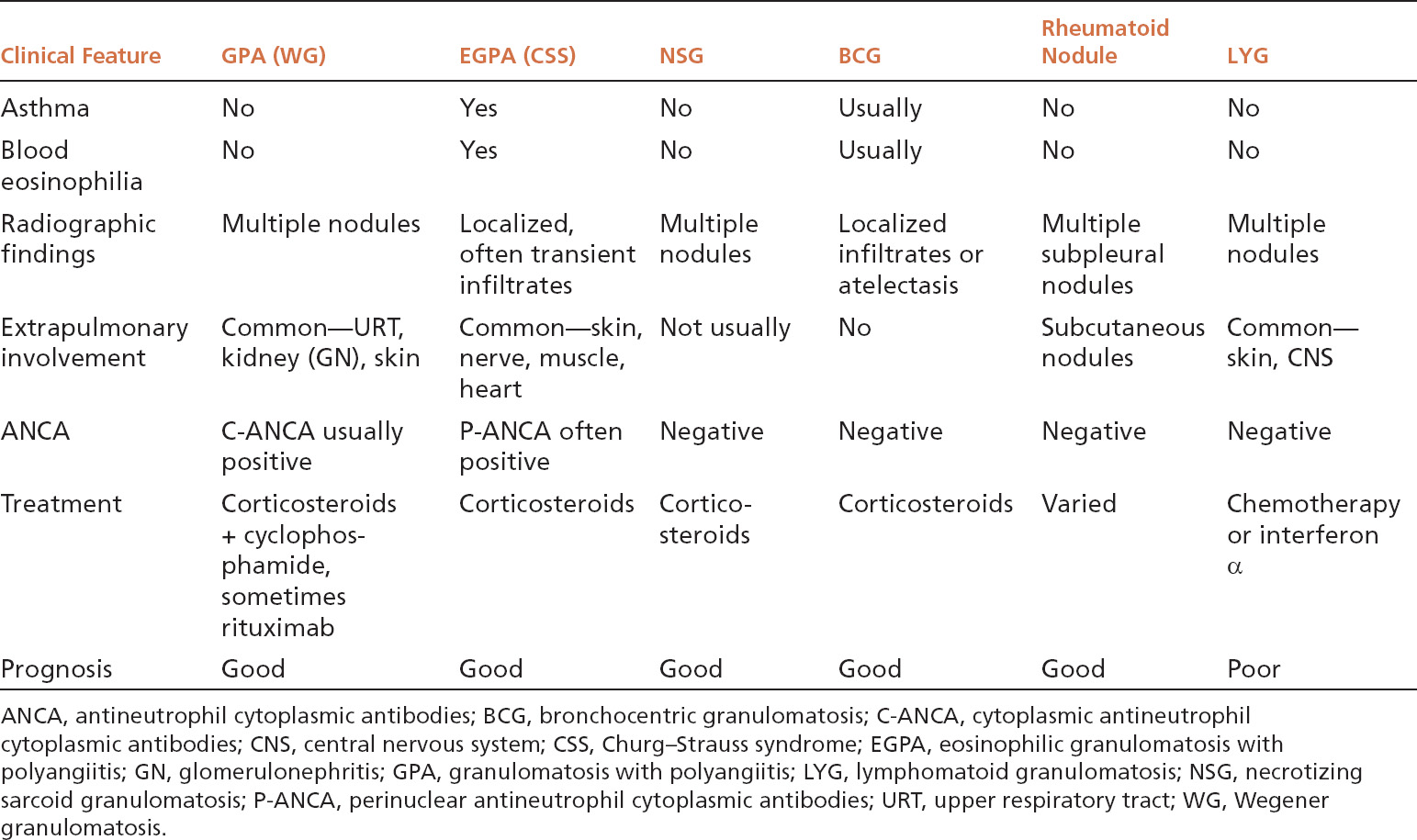

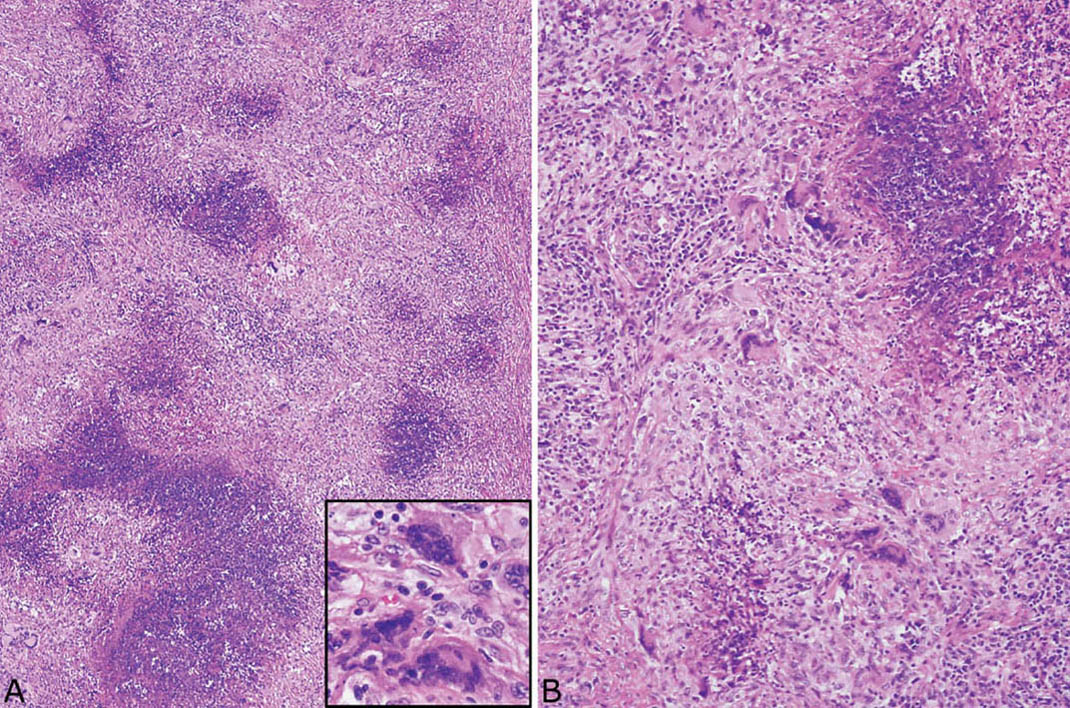

Extensive replacement of lung parenchyma by necrotizing granulomatous inflammation is characteristic. The necrotic zones are typically irregular (“geographic”) in shape and randomly distributed, and they often have a basophilic, “dirty” appearance at least focally caused by the presence of abundant nuclear debris (Figures 6.1 and 6.2). Necrotic neutrophils are often prominent within the debris, and occasionally can be as numerous in places as to initially suggest an abscess (Figure 6.3). The necrotizing process may secondarily destroy bronchioles, but the changes should not be confused with bronchocentric granulomatosis (BCG; see subsequent section “Bronchocentric Granulomatosis”). Rare cases in which bronchiole involvement is prominent have been termed “bronchocentric variant of WG.”

A mixed inflammatory cell infiltrate along with variable fibrosis is present around the necrotic zones and includes, in addition to the characteristic epithelioid histiocytes, acute and chronic inflammatory cells and often deeply staining multinucleated giant cells that stand out even at low magnification (Figures 6.1 and 6.2). Eosinophils are usually not numerous, although rare cases (termed “eosinophilic variant of WG”) have been reported. Small suppurative or palisading granulomas are common findings as well and consist of central, rounded necrotic foci containing karyorrhectic neutrophils or other cellular debris surrounded by a rim of epithelioid histiocytes arranged with their long axis perpendicular to the center (Figure 6.4). It is important to note, however, that well-formed, “sarcoid-like,” non-necrotizing granulomas are not a feature. Random foci of collagen destruction may also be found and are characterized by deeply eosinophilic, necrotic collagen fibers intermixed with necrotic neutrophils or surrounded by palisading histiocytes (Figure 6.5).

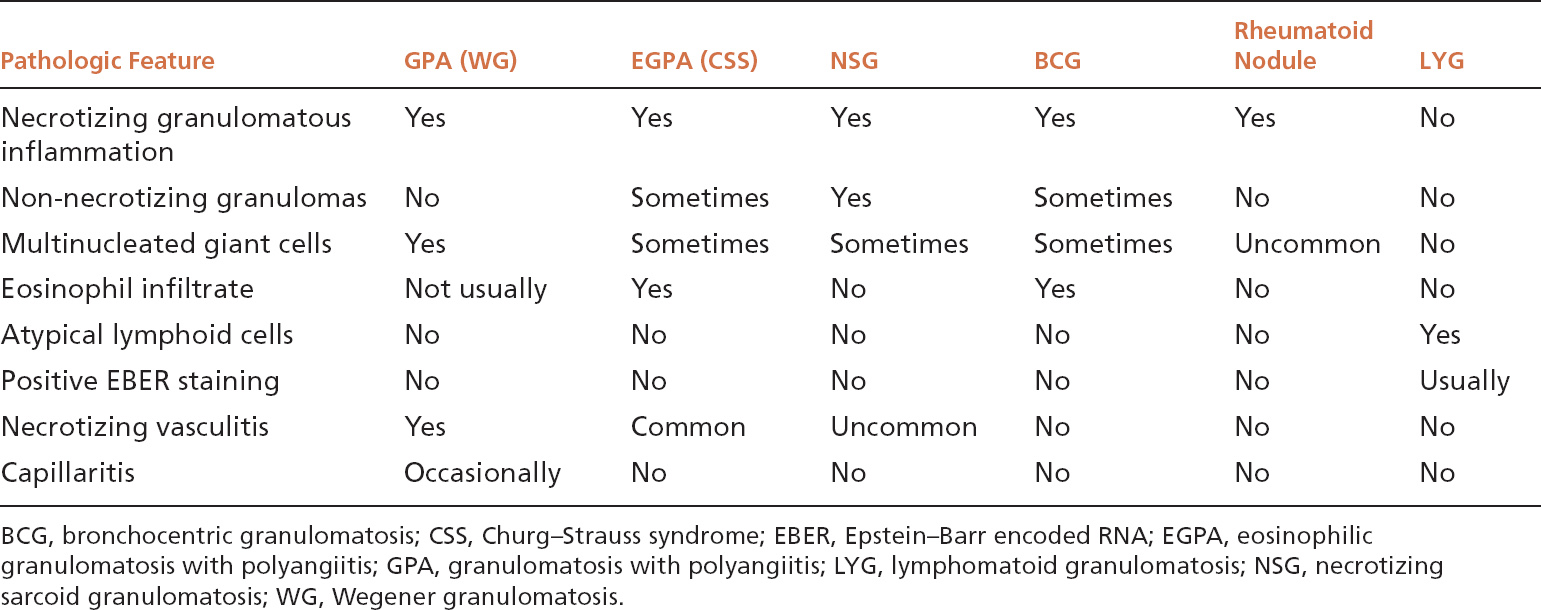

TABLE 6.1 Contrasting Pathologic Features of Necrotizing Noninfectious Lung Lesions

TABLE 6.2 Contrasting Clinical Features of Necrotizing Noninfectious Lesions

Although the aforementioned features by themselves are highly suggestive of GPA, a necrotizing vasculitis must be identified to establish an unequivocal histologic diagnosis. Strict criteria for diagnosing a necrotizing vasculitis must be present, including necrosis in either portions of the blood vessel wall or in the infiltrating inflammatory cells. The vasculitis is generally identified in inflamed but viable parenchyma adjacent to necrotic zones, and only rarely found within uninflamed parenchyma (Figures 6.6–6.8). Blood vessels within necrotic zones, however, may be secondarily inflamed and necrotic, and should not be interpreted as a true vasculitis. The vasculitis typically involves portions of blood vessel walls in a skip pattern such that intervening areas of relatively intact vessels are present, and a sharp transition from inflamed to normal vessel wall is apparent (Figures 6.7 and 6.8). The entire blood vessel circumference may be involved by the vasculitis in other cases (Figure 6.6), and, when severe, the lumen may be destroyed by the process, with only scattered remnants of smooth muscle left to identify the area as a blood vessel (Figure 6.9). Elastic tissue stains can help in such cases by outlining remnants of vascular elastic tissue, and they may also be used to determine whether the involved blood vessel is an artery or vein (Figure 6.10). They should not be used as a screening tool for vasculitis, however, because they indiscriminately outline secondarily inflamed and necrotic blood vessels that may lead to over-diagnosis of a primary vasculitis.

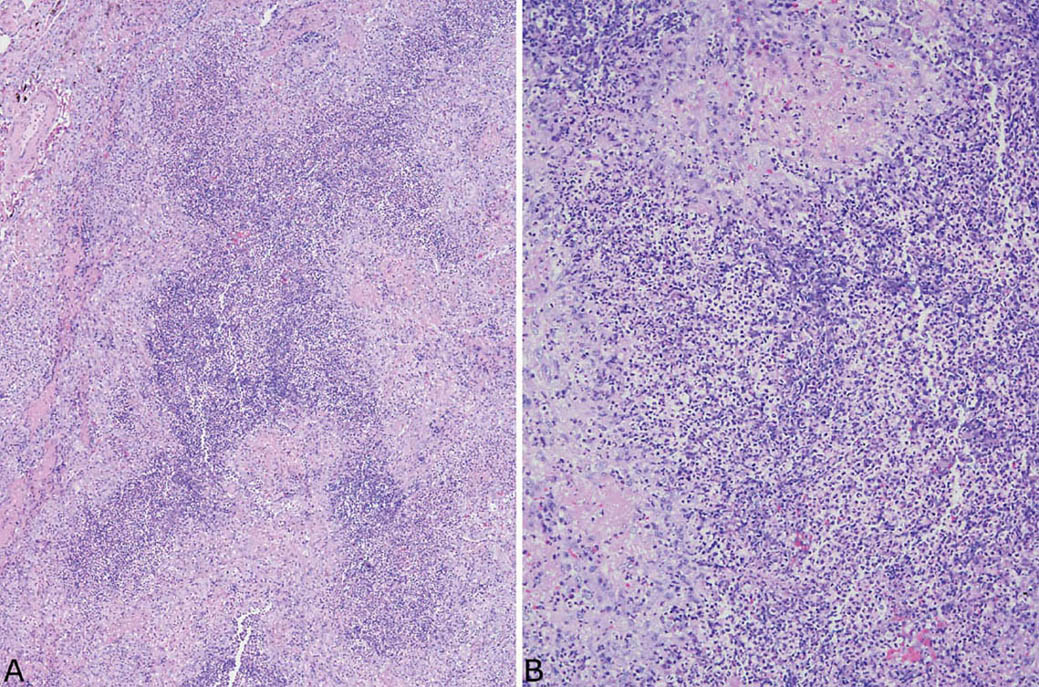

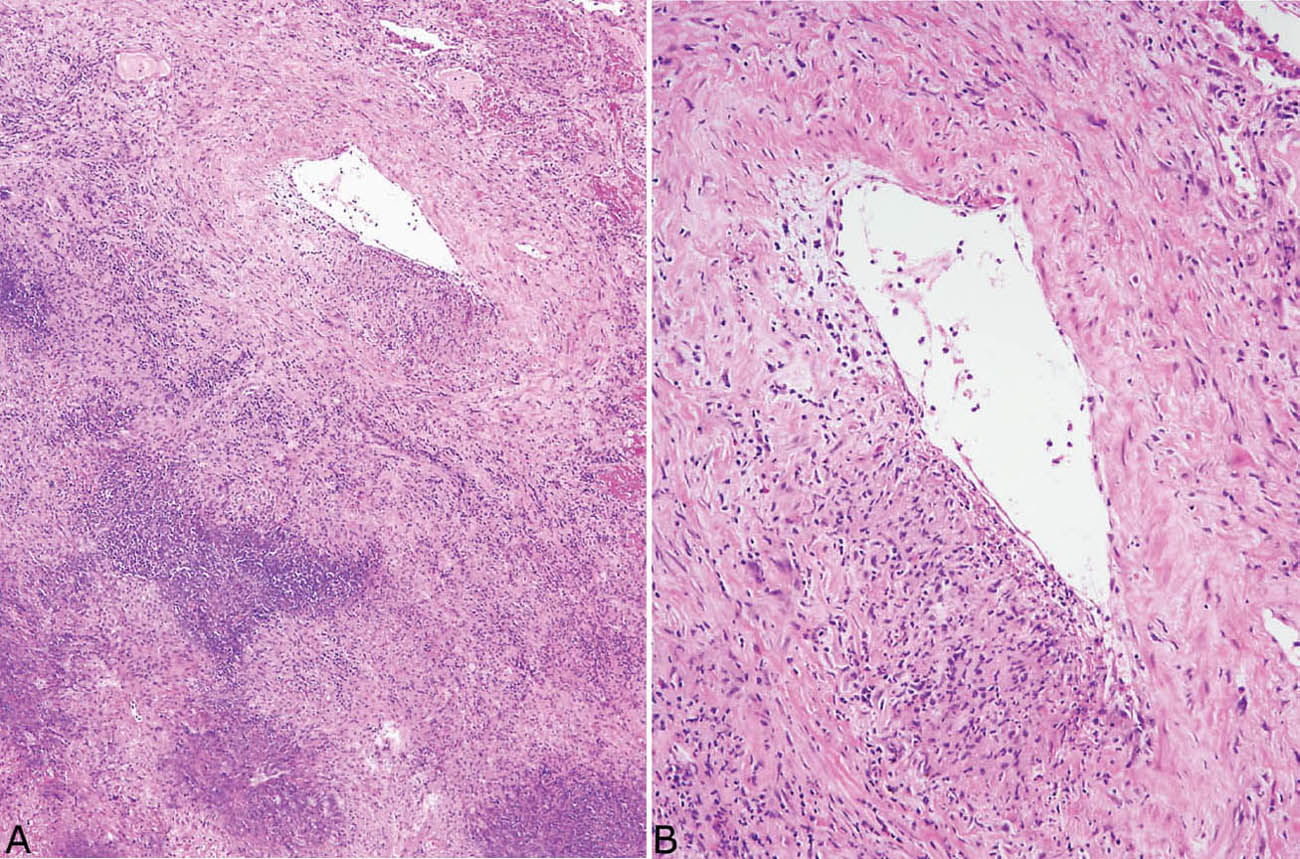

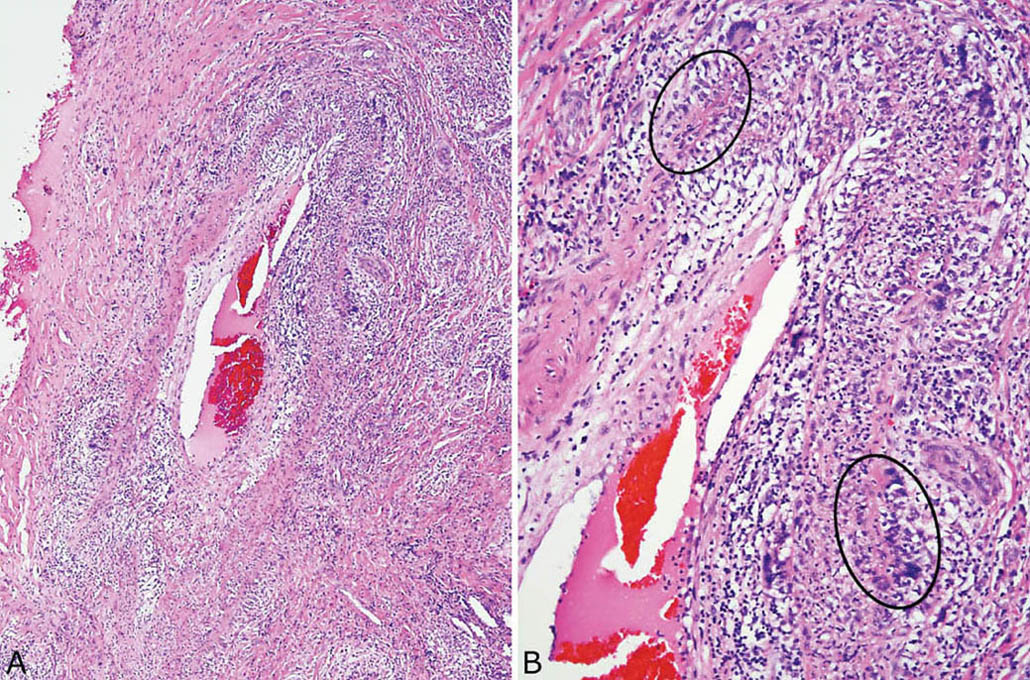

FIGURE 6.1 Classic GPA. (A) Low magnification showing the typical necrotizing granulomatous inflammation with irregular, randomly dispersed basophilic, “dirty,” necrotic zones and surrounding background chronic inflammation and fibrosis. Darkly stained multinucleated giant cells are visible even at low magnification and are highlighted in the inset at high magnification. (B) Higher magnification illustrates the abundant nuclear debris within the necrotic zones and the surrounding epithelioid histiocytes and multinucleated giant cells. GPA, granulomatosis with polyangiitis.

FIGURE 6.2 Classic GPA. (A) In this example, the appearance of the necrotic zones varies from granular, basophilic to more homogeneous, eosinophilic. The irregular, infiltrative, geographic configuration is best appreciated at the junction with viable parenchyma (left). (B) Higher magnification shows the nuclear debris comprising the granular, basophilic necrosis along with the surrounding cellular infiltrate containing multinucleated giant cells. GPA, granulomatosis with polyangiitis.

FIGURE 6.3 Classic GPA. (A) In this example, necrotic neutrophils predominate within the necrotic areas, which may initially suggest an abscess except for the thick rim of epithelioid histiocytes. (B) Higher magnification showing the necrotic neutrophils surrounded by granulomatous inflammation. GPA, granulomatosis with polyangiitis.

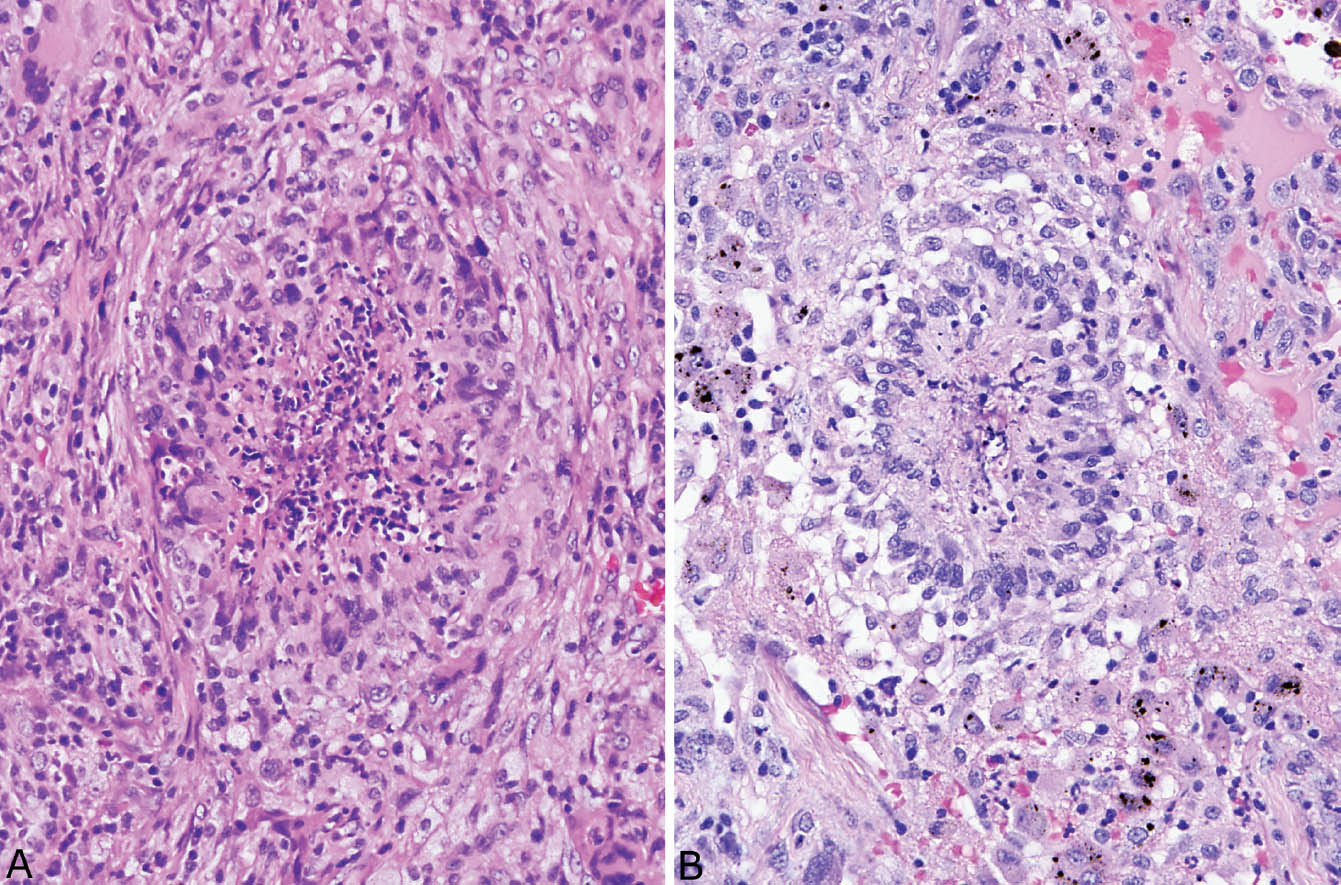

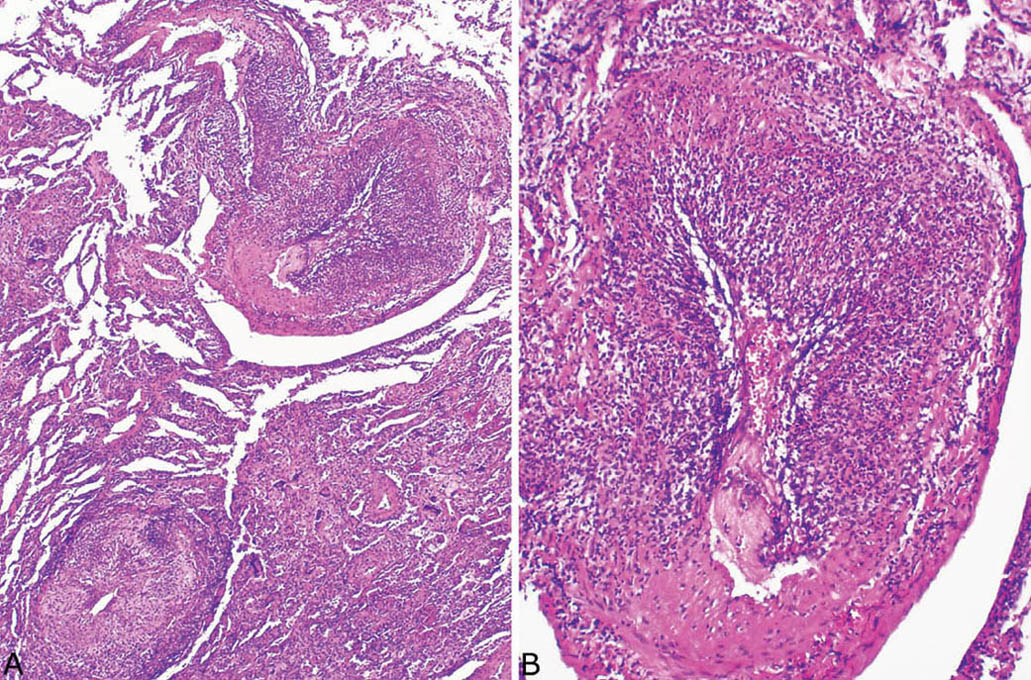

FIGURE 6.4 Palisading granulomas in classic GPA. (A) This tiny granuloma has central necrotic neutrophils bounded by a prominent rim of epithelioid histiocytes that are focally (bottom) arranged with their long axis perpendicular to the center. (B) In this example, palisading histiocytes are more prominent surrounding central nuclear debris. GPA, granulomatosis with polyangiitis.

FIGURE 6.5 Collagen necrosis in classic GPA. (A) In this focus, darkly staining eosinophilic collagen bundles (center) are surrounded by necrotic acute inflammation and peripheral focally palisading (upper right) epithelioid histiocytes. (B) In this example, the central necrotic collagen is completely surrounded by palisading histiocytes. GPA, granulomatosis with polyangiitis.

The composition of the vascular inflammation varies from area to area. Most typically there is a mixture of acute and chronic inflammation with numerous neutrophils and lesser numbers of lymphocytes. Histiocytes are usually prominent as well, and multinucleated giant cells may be seen. Occasionally, well-formed granulomatous inflammation is seen, and necrotic collagen and smooth muscle may be engulfed by the granulomatous process (Figure 6.11). Nuclear debris is present, at least focally, although fibrinoid necrosis is uncommon. Sometimes a necrotizing capillaritis may be encountered in addition to the vasculitis involving arteries and veins, but is usually focal. It is characterized by collections of acute inflammation with variable numbers of histiocytes that infiltrate, expand, and destroy portions of alveolar septa (Figure 6.12; see also subsequent section, “Hemorrhage and Capillaritis GPA”).

Bronchiolitis Obliterans–Organizing Pneumonia–Like GPA

As in classic GPA, granulomatous inflammation and necrotizing vasculitis are necessary to diagnose this variant. The difference is that necrosis is minimal or absent, and, instead, areas of parenchyma are replaced with fibrosis, chronic inflammation, and organizing pneumonia (“BOOP”; Figure 6.13). Loose granulomatous inflammation and small suppurative granulomas can usually be found within the inflamed parenchyma along with characteristic darkly staining multinucleated giant cells. Necrotizing vasculitis is always present and is usually prominent. It should be remembered that BOOP-like (organizing pneumonia) areas can be found in otherwise typical cases of GPA, and the diagnosis of BOOP-like variant, therefore, should be made only when the extensive necrosis of classic GPA is absent.

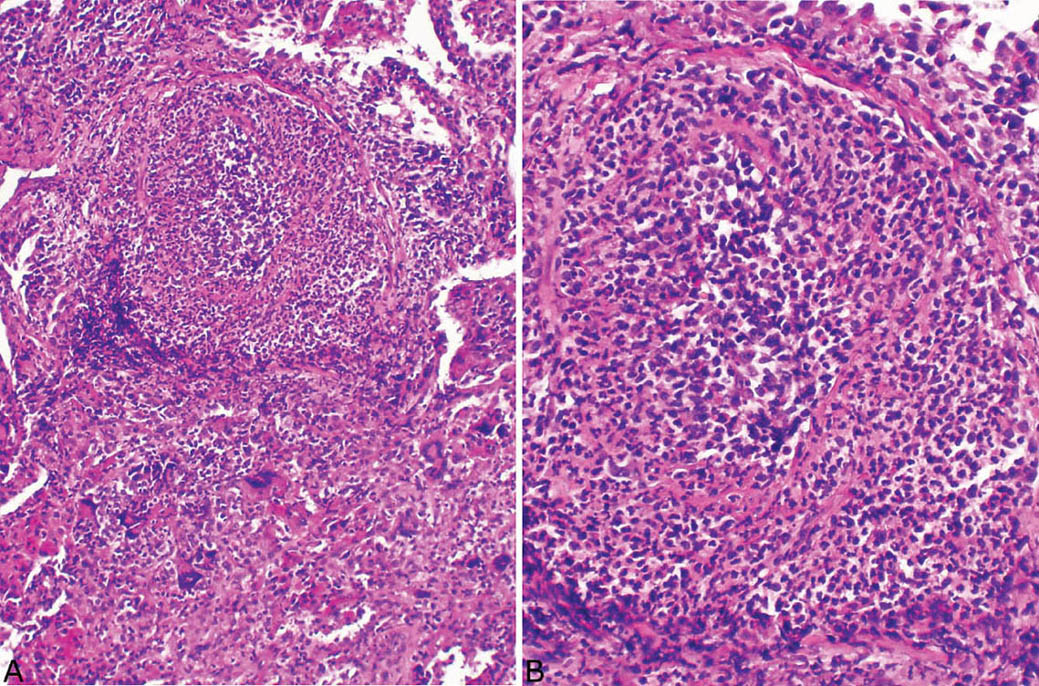

FIGURE 6.6 Necrotizing vasculitis in GPA. (A) Vasculitis (arrows) is present directly adjacent to severely inflamed parenchyma. (B) Higher magnification of the artery at lower left in (A) shows circumferential inflammation and destruction of vessel wall. Note the nuclear debris with areas of fibrinoid necrosis. GPA, granulomatosis with polyangiitis.

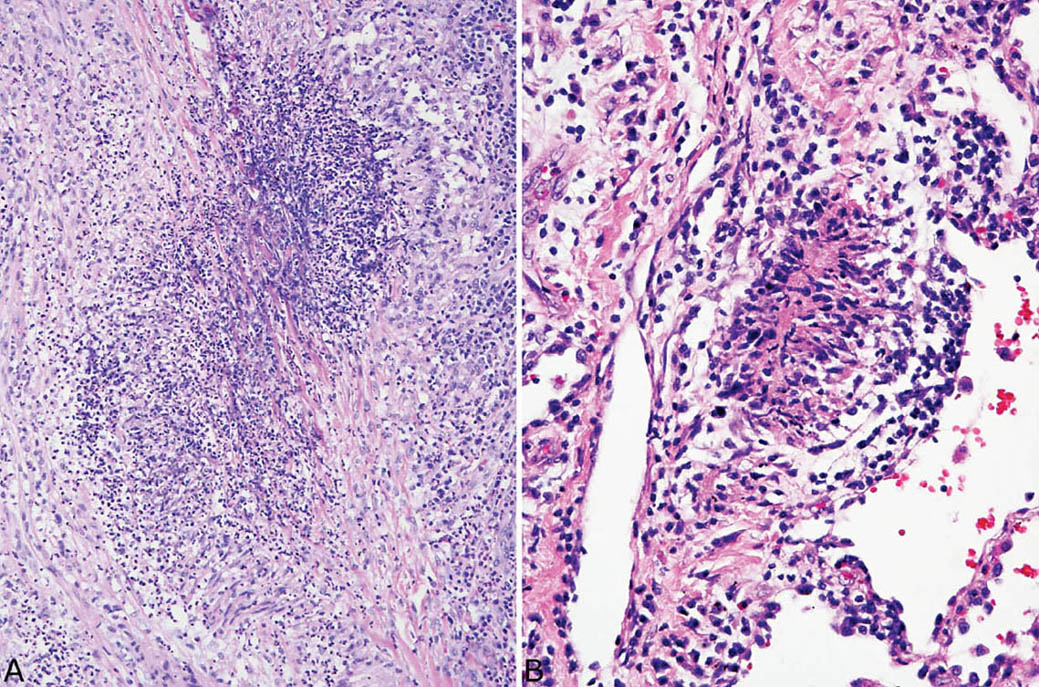

FIGURE 6.7 Necrotizing vasculitis in GPA. (A) In this example, the vasculitis is seen in a portion of artery wall near, but not within, the necrotic zone. (B) Higher magnification shows the typical focal or eccentric involvement of artery wall by inflammation and necrosis. GPA, granulomatosis with polyangiitis.

FIGURE 6.8 Necrotizing vasculitis in GPA. (A) In this example, severe vasculitis involves a blood vessel (top) that is present within nearly normal parenchyma. The involved blood vessel at the bottom directly abuts inflamed parenchyma. (B) Higher magnification of the upper blood vessel in (A) showing partial replacement of vessel wall by the necrotizing inflammatory process. Note the sharp demarcation of the inflamed portion from the normal vessel wall at the bottom. GPA, granulomatosis with polyangiitis.

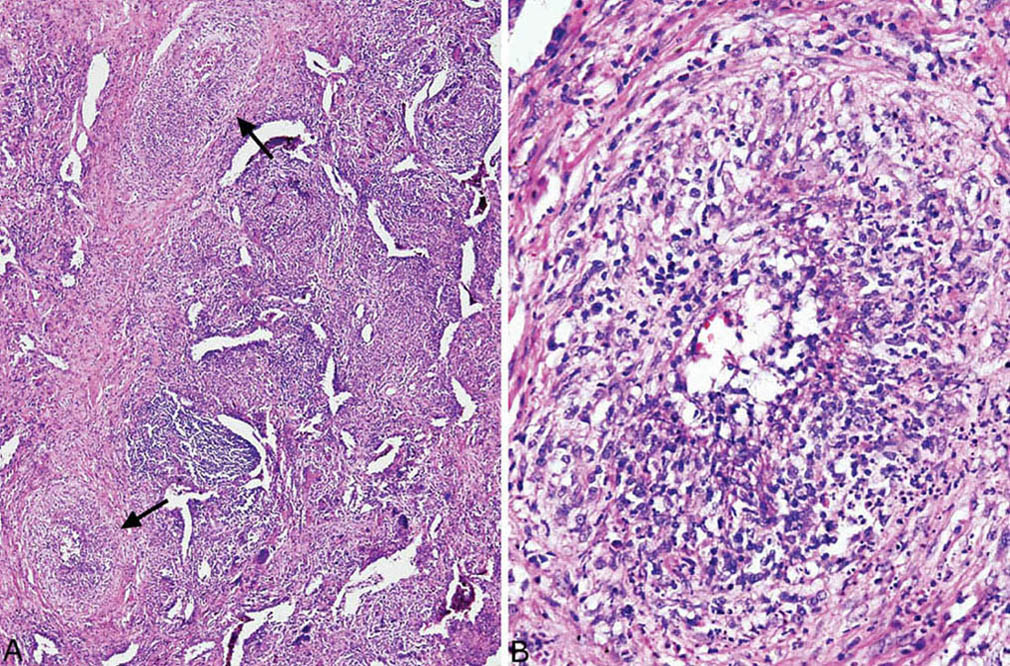

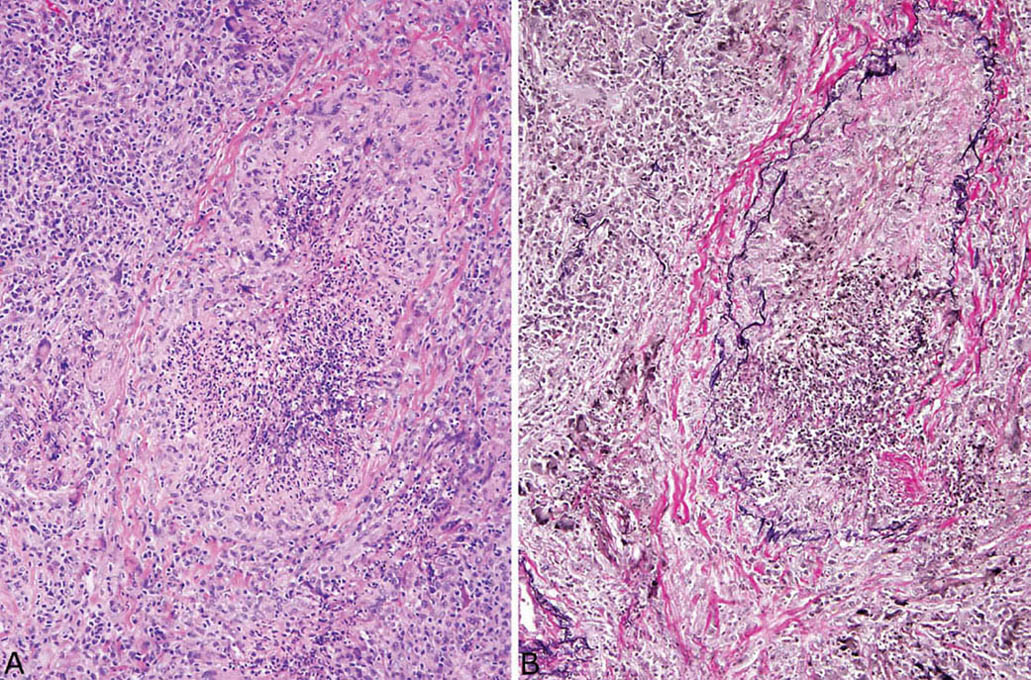

FIGURE 6.9 Necrotizing vasculitis in GPA. (A) The blood vessel at top is nearly destroyed by the inflammatory infiltrate and barely recognizable. (B) At higher magnification, remnants of the muscle layer of the media along with adventitia can be appreciated. GPA, granulomatosis with polyangiitis.

FIGURE 6.10 Necrotizing vasculitis in GPA. (A) In this example, the central inflamed and necrotic structure is barely recognizable as a blood vessel. Note the background chronic inflammation with scattered giant cells. (B) An elastic tissue stain clearly outlines remnants of vascular elastic tissue confirming that the structure is a blood vessel, likely a vein. GPA, granulomatosis with polyangiitis.

FIGURE 6.11 Necrotizing vasculitis in GPA. (A) In this example, multinucleated giant cells and small palisading granulomas are present in addition to other inflammatory cells in an artery wall. (B) The palisading granulomas (circles) are better appreciated at higher magnification. GPA, granulomatosis with polyangiitis.

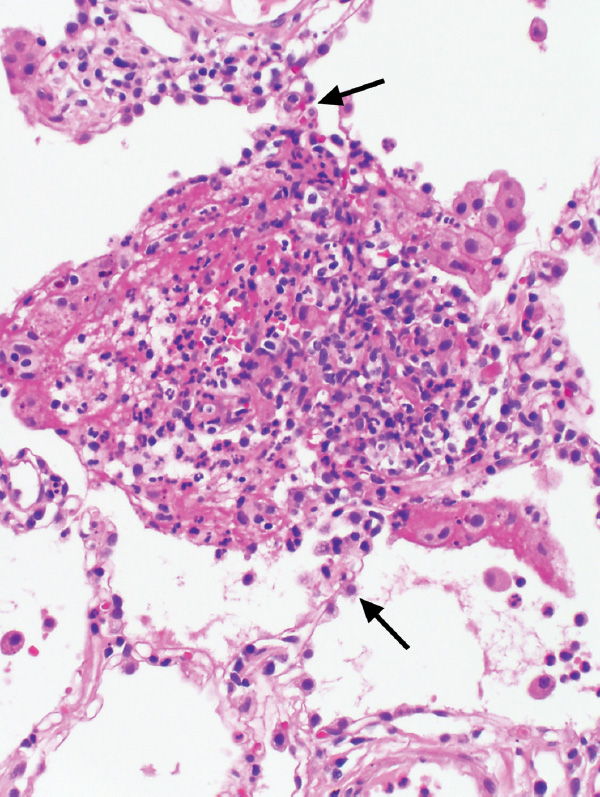

FIGURE 6.12 Capillaritis in GPA. In this field, the alveolar septum (arrows) is expanded and destroyed by a mixture of acute inflammatory cells and histiocytes along with a fibrinous and hemorrhagic exudate. The findings mark a destroyed alveolar septal capillary. The capillaritis in this case was a focal finding in an otherwise typical case of classic GPA. GPA, granulomatosis with polyangiitis.

Hemorrhage and Capillaritis GPA

The hemorrhage and capillaritis syndromes, including GPA, are discussed in detail in Chapter 4. Briefly, this form of GPA is characterized by a combination of intra-alveolar hemorrhage and patchy interstitial acute inflammation that expands and destroys portions of alveolar septa (capillaritis, Figure 6.14; see also Figures 4.27–4.29). Granulomatous inflammation is not present, and although there may be focal, accompanying arteriolitis, vasculitis is not seen in arteries or veins. Eosinophils and histiocytes may accompany the interstitial acute inflammation, and their presence, although not specific, favors GPA over other causes of hemorrhage and capillaritis.

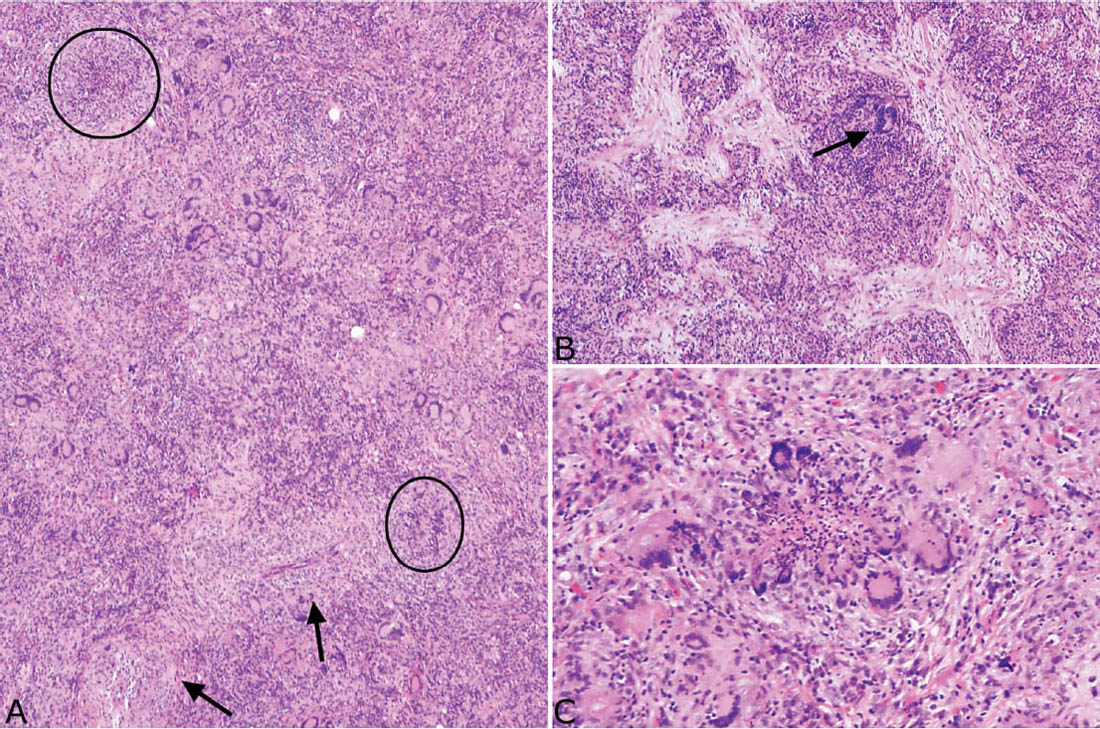

FIGURE 6.13 BOOP-like GPA. (A) In this low magnification view, loose granulomatous inflammation with numerous giant cells, chronic inflammation, and fibrosis replaces parenchyma. Vasculitis is prominent (arrows) and tiny palisading granulomas (circles) are present, but characteristic large necrotic zones of GPA are absent. (B) In this field from the same case, organizing pneumonia is prominent within the inflamed parenchyma. Characteristic darkly staining multinucleated giant cells (arrow) are also present and are a clue to the diagnosis. (C) Higher magnification of a typical small suppurative, palisading granuloma from the same case. BOOP, bronchiolitis obliterans–organizing pneumonia; GPA, granulomatosis with polyangiitis.

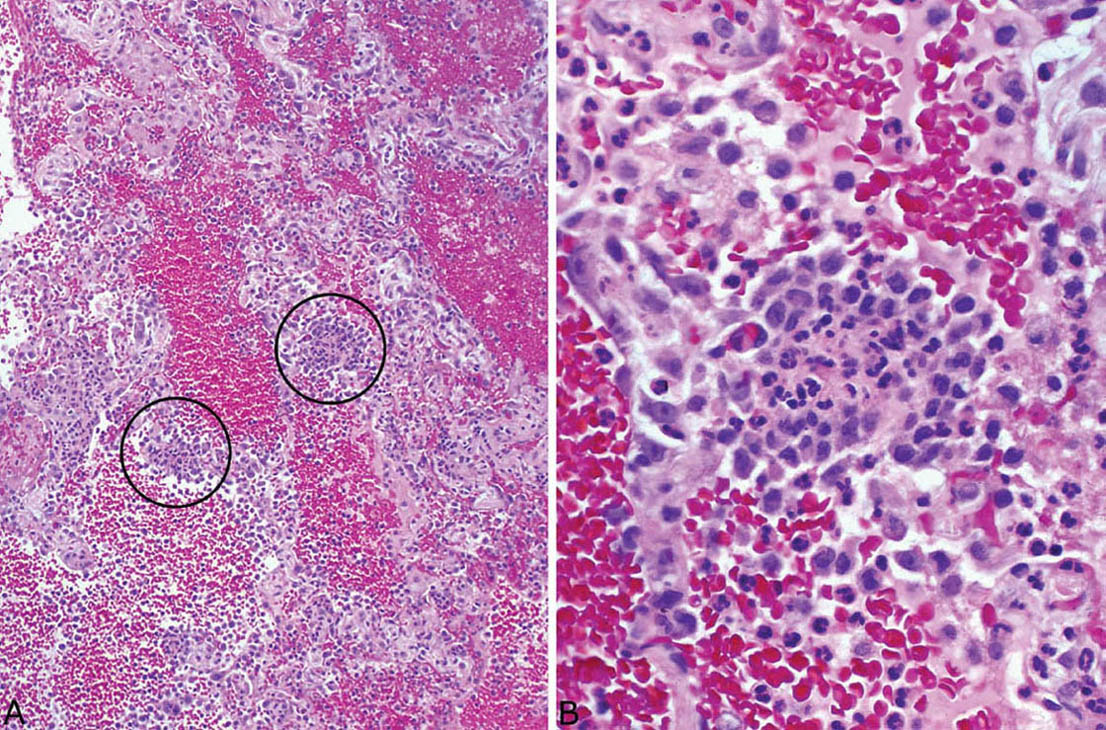

FIGURE 6.14 Hemorrhage and capillaritis variant of GPA. (A) Prominent intra-alveolar hemorrhage is seen at low magnification along with a patchy inflammatory cell infiltrate within alveolar septa (circles). (B) Higher magnification shows foci of necrotic neutrophils surrounded by epithelioid histiocytes that expand and destroy the alveolar wall, changes indicative of a necrotizing capillaritis. GPA, granulomatosis with polyangiitis.

Differential Diagnosis

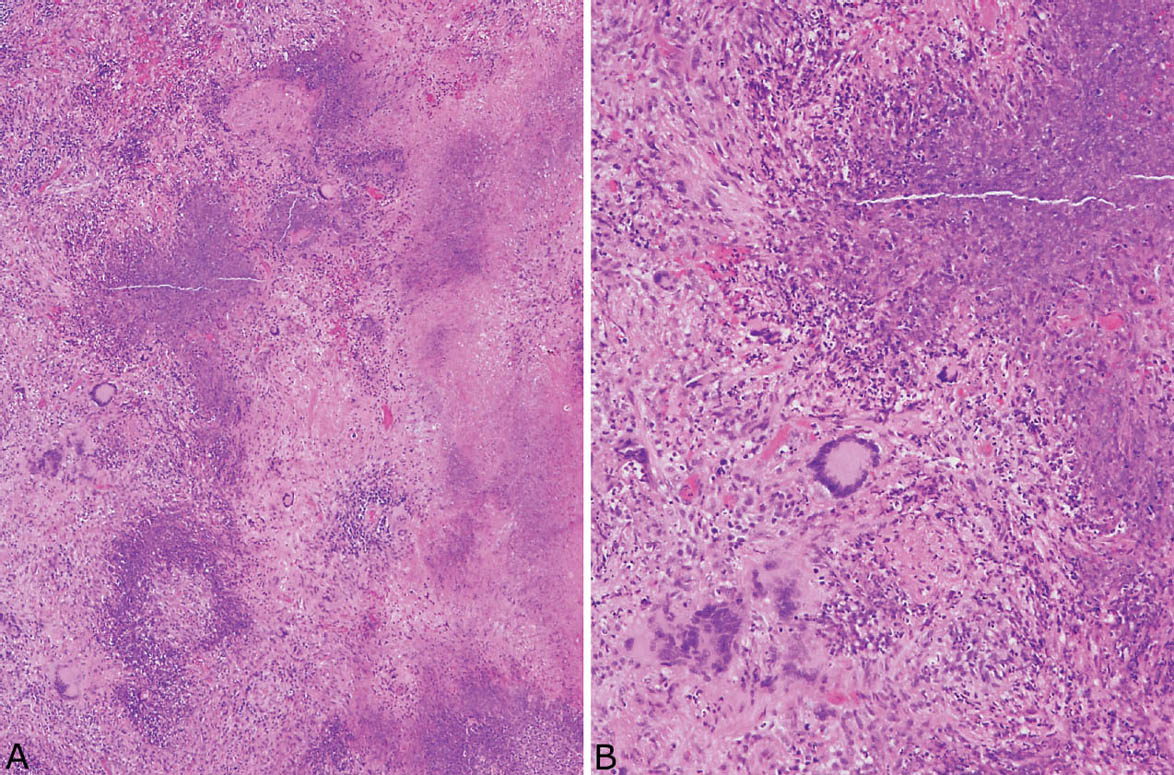

The main lesion in the differential diagnosis of the granulomatous forms of GPA is a granulomatous infection. Of course, special stains and cultures should be performed in all cases, but the diagnosis is often needed before the results of cultures are known. The key feature in support of GPA is the presence of a necrotizing vasculitis. Although vascular inflammation is common in infectious granulomas and it may be prominent, accompanying vascular wall necrosis is not a feature (Figure 6.15). It should be remembered, however, that blood vessels within necrotic centers of infectious granulomas commonly are secondarily inflamed and necrotic and should not be interpreted as a primary vasculitis.

The alveolar hemorrhage syndromes are the main entities in the differential diagnosis of the hemorrhage and capillaritis variant of GPA, and they are reviewed in Chapter 4.

Clinical Findings

GPA is a systemic vasculitis that may manifest a classic triad of upper respiratory and lower respiratory tract involvement along with glomerulonephritis. Only one or two of the classic sites may be involved, however, and other organs may be affected as well, including especially skin, joints, middle ear, eye, and nervous system. Lung is occasionally the sole organ of involvement, and diagnosis in such cases can be especially challenging for the pathologist.

Most patients with GPA are middle-aged adults with an average age of 45 to 55 years, although there is a wide age range and cases may occur in children and the elderly. Fever, malaise, weight loss, cough, chest pain, and hemoptysis are the most common presenting complaints. Radiographically, multiple, often cavitary, nodular densities are usually seen, whereas localized consolidation and solitary nodules occur less often. Diffuse bilateral infiltrates are typically seen in the hemorrhage and capillaritis variant. Patients are usually treated with a combination of corticosteroids and cyclophosphamide with good response and a 5-year survival greater than 80%. Recently, rituxamide has been added to the regimen for poorly responding cases or relapses with apparent additional benefit.

Testing for serum antineutrophil cytoplasmic antibodies (ANCA) is an important part of the work-up of GPA. The finding of cytoplasmic (C)-ANCA (proteinase 3 [PR3]-ANCA) is highly specific for GPA, provided that the clinical situation fits. A few cases may instead be positive for perinuclear (P)-ANCA (myeloperoxidase [MPO]-ANCA), although P-ANCA is considerably less specific. C-ANCA are found in more than 90% of generalized GPA cases, whereas only 60% of localized GPA are positive. A positive test in the right clinical setting not only supports the diagnosis but also may obviate the need for biopsy. A negative test, however, does not exclude the diagnosis and should not sway the pathologist away from the diagnosis if characteristic histologic changes are present.

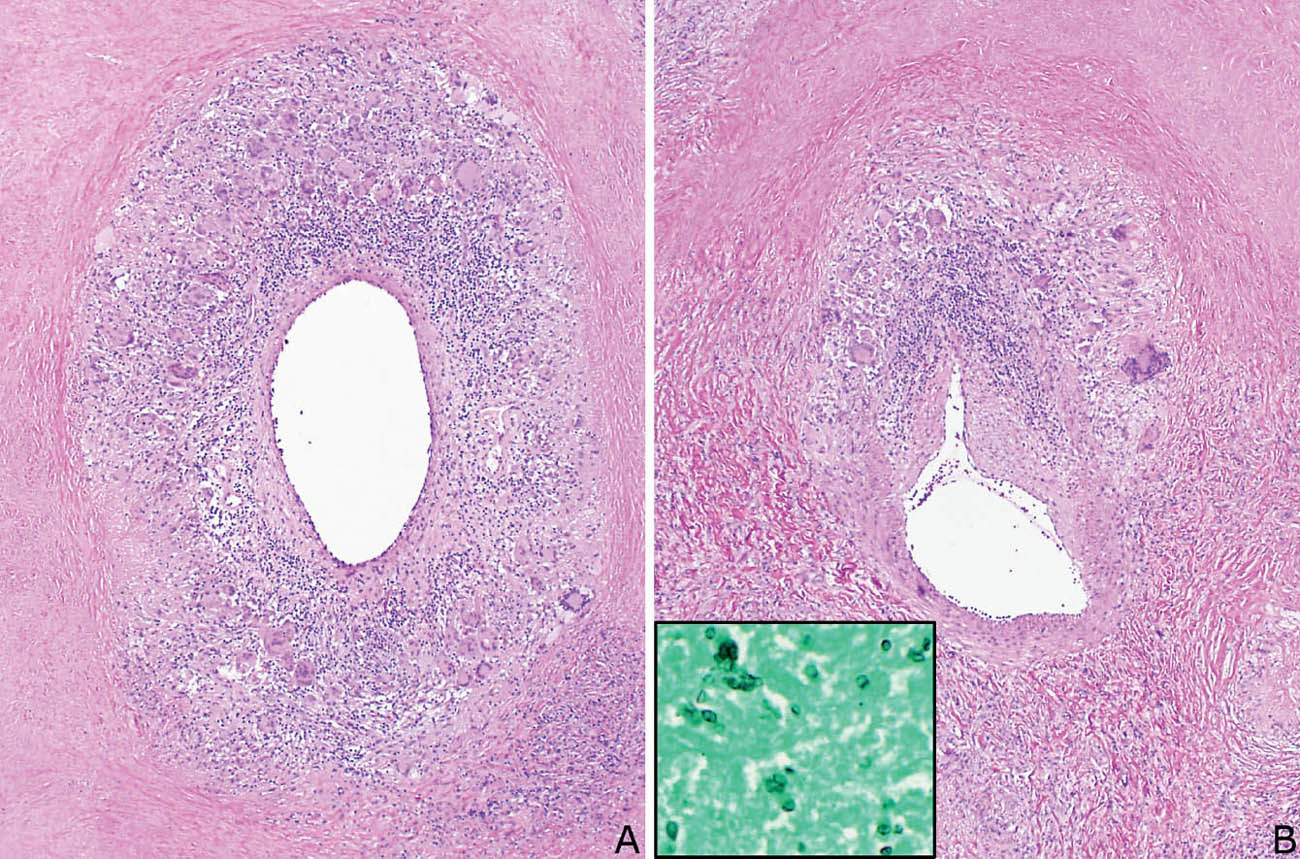

FIGURE 6.15 Vasculitis in granulomatous infection. (A) Circumferential granulomatous and chronic inflammation involves this blood vessel from a case of histoplasmosis. Note that the vessel is present within an area of necrosis. (B) This blood vessel from the same case is present partly within the necrosis (top) and partly on the viable edge (bottom), and it is eccentrically involved by the inflammation. Although inflamed, neither vessel shows necrosis. Inset is a GMS stain showing histoplasma yeasts noted within the necrotic zones. GMS, Gomori methenamine silver.

Helpful Tips—GPA

Well-formed non-necrotizing granulomas are not features of GPA, and, if present, should suggest another diagnosis.

Well-formed non-necrotizing granulomas are not features of GPA, and, if present, should suggest another diagnosis.

Do not use elastic tissue stains to search for necrotizing vasculitis, as it may lead to over-diagnosis.

Do not use elastic tissue stains to search for necrotizing vasculitis, as it may lead to over-diagnosis.

A negative C-ANCA test does not exclude GPA; do not waiver from the diagnosis if typical histologic findings with necrotizing vasculitis are present.

A negative C-ANCA test does not exclude GPA; do not waiver from the diagnosis if typical histologic findings with necrotizing vasculitis are present.

When all characteristic histologic features are present except necrotizing vasculitis, and special stains for organisms are negative, the diagnosis can be suggested, although not definitively diagnosed from the histologic findings alone; clinical findings and/or positive C-ANCA may confirm the diagnosis.

When all characteristic histologic features are present except necrotizing vasculitis, and special stains for organisms are negative, the diagnosis can be suggested, although not definitively diagnosed from the histologic findings alone; clinical findings and/or positive C-ANCA may confirm the diagnosis.

An inflammatory infiltrate within blood vessel walls, which may be granulomatous, is common in infections, and, in the absence of necrosis, is not indicative of a primary vasculitis. Careful search of such cases with special stains for organisms should be performed.

An inflammatory infiltrate within blood vessel walls, which may be granulomatous, is common in infections, and, in the absence of necrosis, is not indicative of a primary vasculitis. Careful search of such cases with special stains for organisms should be performed.

EOSINOPHILIC GRANULOMATOSIS WITH POLYANGIITIS (EGPA) (FORMERLY CHURG–STRAUSS SYNDROME) (CSS)

Eosinophilic granulomatosis with polyangiitis (EGPA), better known as Churg–Strauss syndrome (CSS) or allergic angiitis and granulomatosis, is another systemic vasculitis that often involves the lungs. The diagnosis, however, is usually made from clinical findings, and biopsy of extrapulmonary sites. Lung biopsy, however, may be taken in clinically unsuspected cases or in cases with predominant lung involvement.

Histologic Features

The presence of the following three features is considered diagnostic of EGPA. However, finding all three together in a single case is uncommon, and when only one or two are present, the diagnosis may be suggested by the pathologist but ultimately rests on supportive clinical features.

Areas of eosinophilic pneumonia

Areas of eosinophilic pneumonia

Necrotizing granulomatous inflammation with eosinophil infiltrate

Necrotizing granulomatous inflammation with eosinophil infiltrate

Vasculitis with eosinophils

Vasculitis with eosinophils

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree