LEARNING OBJECTIVES

Learning Objectives

The student will be able to describe the features of latent infection and disease caused by Mycobacterium tuberculosis.

The student will be able to recognize characteristic radiographic patterns of the pulmonary disease caused by Mycobacterium spp.

The student will be able to explain the epidemiology of nontuberculous mycobacterial diseases in specific clinical conditions including cystic fibrosis, bronchiectasis, COPD, and other structural diseases of the lungs.

The student will be able to develop treatment approaches for clinical cases of pulmonary mycobacterial disease.

Mycobacterial diseases of the lung encompass tuberculous and nontuberculous diseases, which have important differences in pathogenesis, transmissibility, therapeutic approach, and public health implications. The incidence of tuberculosis (TB) disease from Mycobacterium tuberculosis began to significantly rise by approximately 20% in the United States after 1985 due to combination of factors; namely, emergence of human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) infection, increased immigration of persons from region of high TB activity and drug resistance, and increased numbers of medically underserved individuals such as drug abusers and homeless populations. Although at least 15 million persons are infected with TB in the United States, the actual number of cases has been decreasing since 1992, primarily due to more effective public health policies, enhanced awareness resulting in earlier diagnosis, and implementation of directly observed therapy (DOT) as standard of care in appropriate settings.

The present incidence of tuberculosis in the United States varies significantly depending on the place of birth of U.S. nationals. It is as high as 20.6 cases per 100,000 persons among foreign-born individuals versus 2.1 cases per 100,000 among U.S. born persons, respectively. In 2007, moreover, foreign-born persons accounted for approximately 60% of new cases in the United States. These data underscore the importance of ongoing overseas screening for tuberculosis with follow-up evaluation after arrival in U.S. bound immigrants. Elimination of tuberculosis in the United States therefore mandates control and prevention of tuberculosis in foreign-born persons.

MYCOBACTERIUM TUBERCULOSIS INFECTION

Development of disease from Mycobacterium tuberculosis (MTB) is the most common global infectious cause of death. Such disease caused by bacteria of the MTB complex preeminently affects the lungs, although other organs are involved in up to one-third of cases. Transmission of TB occurs when a contagious patient cough, sneezes, or otherwise spreads the bacilli through generation of airborne droplet nuclei to individuals in close proximity sharing the same ventilatory space. Of note, M. bovis belonging to the MTB complex is transmitted by ingestion of contaminated, unpasteurized dairy products from infected cattle. M. tuberculosis is a rod shaped, non-spore-forming, nonmotile, thin aerobic bacterium measuring 0.5 μm × 3 μm. Mycobacteria, including M. tuberculosis, are often neutral on Gram stain; however, once stained, the bacilli are not easily decolorized by acid alcohol and hence the classification acid-fast bacilli (AFB) (Fig. 36.1; see also Fig. 34.15).

Other microorganisms may also display some acid fastness, including species of Nocardia and Rhodococcus, Legionella micdadei, and the protozoa Isospora and Cryptosporidium. With respect to the mycobacteria, the cell wall contains lipids (eg, mycolic acids) that are linked to underlying arabinogalactan and peptidoglycan residues. These collectively confer low permeability characteristics to the cell wall, and so reduce the effectiveness of most antimicrobial drugs.

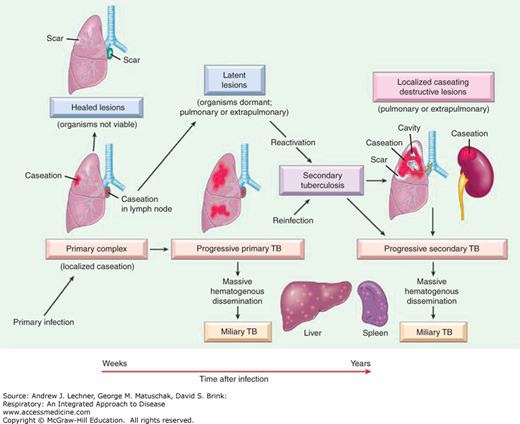

Tuberculosis is broadly classified as pulmonary or extrapulmonary; pulmonary tuberculosis represents the majority of disease cases. Tubercle bacilli on droplet nuclei are inhaled into the respiratory zone of the host’s lungs after exposure to contagious individuals, especially in crowded conditions. MTB bacilli are deposited in the small airways and the alveoli of better-ventilated areas of the lung. This is typically the middle to lower regions (lower lobes) in adults. After phagocytosis by alveolar macrophages, MTB organisms undergo intra-cellular replication. The initial inflammatory response to the MTB infection in the lung is referred to as a primary or Ghon focus. MTB organisms can thereafter spread, during this early stage, via the lymphatics to the draining lymph nodes and result in hilar or mediastinal lymphadenopathy. Alternatively, the bacilli may enter the bloodstream and spread hematogenously to other organs of the body. Disease presenting at this stage is called primary tuberculosis (Fig. 36.2).

However, more commonly the host develops cell-mediated immune reaction involving alveolar macrophages that phagocytize tubercle bacilli, and CD4+ T lymphocytes, which induce protection through the production of cytokines, mainly interferon-γ (IFN-γ). Coincident with the development of immunity, delayed-type hypersensitivity to M. tuberculosis develops. This stage is referred to as latent TB infection and is the basis of tuberculin skin testing. In most instances, the immune response successfully controls the tuberculosis infection although 3%-5% of infected subjects progress to active disease within 2 years, termed progressive primary TB (Fig. 36.2). Primary tuberculosis is common among at-risk children up to 4 years of age. Furthermore, among infected individuals, the incidence is highest during late adolescence and early adulthood.

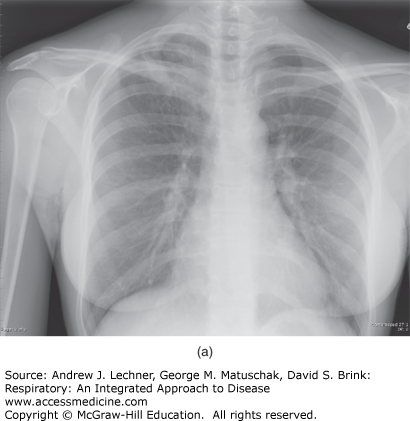

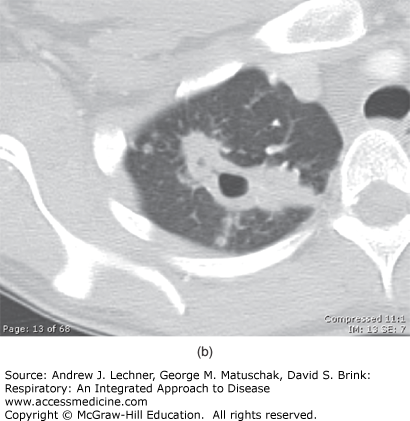

Because the healed primary infected lung foci often contain bacilli that are viable for many years, progression to subsequent disease can occur if the immunity wanes, which is referred to as post-primary or reactivation pulmonary tuberculosis. Overall, individuals infected with MTB have a 5%-10% risk of reactivation during their lives, particularly in the setting of several well-defined risk factors culminating in relative degrees of immunosuppression (Table 36.1). In this context, the risk of developing TB disease after infection depends largely on the host’s innate susceptibility to the disease and level of function of cell-mediated immune responses. Reactivation disease has a predilection for the upper lobes of the lungs as well as having a propensity for cavitation (Fig. 36.3) without accompanying intrathoracic lymphadenopathy. However, the entire pathogenetic sequence represents a continuum and becomes less distinct in conditions of immune deficiency such as in HIV seropositive individuals. Importantly, the distinction between primary and postprimary tuberculosis has questionable clinical relevance, inasmuch as active tuberculosis should always be treated and pharmacological therapy remains similar.

| HIV infection | Underlying cancer | Silicosis | Chemotherapy |

| Diabetes mellitus | Malnutrition | Leukemia | Lymphoma |

| Advanced age | IV drug abuse | Post-gastrectomy | Jejunoileal bypass |

| Renal failure | Hemodialysis | ||

| Immunosuppressive drug therapy (eg, steroids, cytotoxic drugs, TNF-α blockers) | |||

FIGURE 36.3

(a) The chest x-ray of a patient diagnosed with reactivation tuberculosis. Note the right upper lobe air-space opacities with suggestion of cavitary process. (b) CT scan of the chest (lung attenuation window) of the same patient with reactivation (post-primary) TB. Note extensive cavitation due to necrosis of the lung parenchyma and the satellite nodules. The patient (a resident of Colombia in South America) presented to the hospital with hemoptysis while visiting the United States on a business trip.

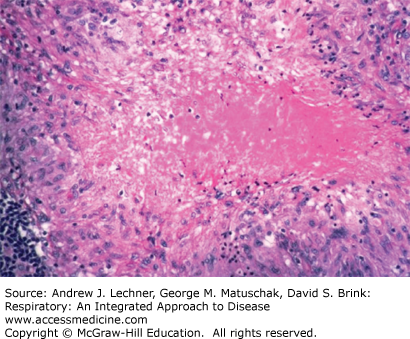

The development of specific immunity results in activation of macrophages and their accumulation in large numbers at the primary site, leading to hallmark pathologic lesion, the necrotizing granuloma. Necrosis results from the tissue damaging effect of delayed-type hypersensitivity. Because the necrotic material resembles soft cheese, it is termed caseous necrosis (Fig. 36.4).

Extrapulmonary tuberculosis can involve lymph nodes (lymphadenitis), pleura (empyema and effusions), genitourinary tract, bones and joints (osteomyelitis), meninges (meningitis), peritoneum (peritonitis), pericardium (pericarditis), gastrointestinal tract, and disseminated disease as a result of hematogenous spread especially in immunocompromised hosts such as those with HIV coinfection.

CLINICAL CORRELATION 36.1

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree