Modified Heller Myotomy

Richard Lazzaro

Joseph LoCicero III

Lendrum11 recognized the significance of incomplete LES relaxation, in relation to the disease symptoms, and proposed the name achalasia in 1937. Patients with achalasia present with a triad of dysphagia, weight loss, and regurgitation. No specific etiology, locally or centrally mediated, has been linked to the pathologic destruction of the myenteric plexus observed in these patients. However, several tenets remain clear. Manometric evaluation demonstrates esophageal body aperistalsis associated with a hypertensive lower esophageal sphincter that fails to relax.

Endoscopy is mandatory to preclude pseudoachalasia secondary to underlying malignancy at the proximal stomach or gastroesophageal junction. Patients with achalasia are predisposed to the development of esophageal squamous cell carcinoma and should undergo lifelong surveillance endoscopy.

The goal of treatment remains palliative and traditionally includes pharmacotherapy (nitrates and calcium channel blockers), pneumatic dilatation, botulinum toxin injection, and esophageal myotomy. Resection is reserved for treatment failures and malignancy.

Approach

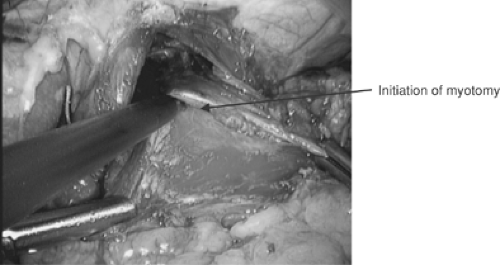

Sir Thomas Willis performed the first successful dilatation for achalasia in 1672, using polished whalebone attached to a sponge. Ernst Heller8 performed the first surgical myotomy in 1914, utilizing anterior and posterior myotomies via thoracotomy. The major modification to Heller’s myotomy is a single anterior myotomy. The procedure has been further modified in recent years by the abdominal approach and minimally invasive thoracic and abdominal approaches.

Owing to concerns over length of stay, postoperative pain, and surgical mortality, the initial treatment has evolved away from the open modified Heller myotomy. In a prospective randomized study in 1989, Csendes et al.6 demonstrated the superiority of cardiomyotomy over forceful dilatation. Csendes also noted that after the procedure, the midesophageal diameter decreased and the lower esophageal sphincter diameter increased (p <0.0001): “this increase was greater in the operated group over the dilated group (p <0.01).”6

The radiographic improvement of treated patients may suggest a return of esophageal function when palliation is successful. Researchers at the University of Washington Swallowing Center evaluated the effect of endoscopic and operative treatment of achalasia on esophageal function. Liquid and viscous clearance rates, dysphagia scores, and return of peristalsis were seen in the treated patients (p <0.05). Of patients who underwent myotomy, 63% exhibited peristalsis postoperatively, compared with 12% preoperatively.22 Schneider and colleagues17 noted that “after Heller myotomy, the return of peristalsis correlates

with esophageal clearance, which may partly explain its superior relief of dysphagia.”

with esophageal clearance, which may partly explain its superior relief of dysphagia.”

Advancements in laparoscopic and thoracoscopic equipment and technique have allowed surgeons to perform a minimally invasive cardiomyotomy. In 1991, Shimi et al.20 reported that they had performed the first laparoscopic myotomy for achalasia. Multiple retrospective data demonstrate the safety as well as palliative benefit of laparoscopic cardiomyotomy over pneumatic dilatation.13,21 There is a solitary published report of a prospective randomized study comparing laparoscopic cardiomyotomy to pneumatic dilatation demonstrating a short-term benefit to laparoscopic cardiomyotomy.10 Laparoscopic cardiomyotomy should be considered first-line treatment of patients with achalasia.

Limitation of the gastric extent of the myotomy to prevent or mitigate gastroesophageal reflux is associated with less relief of dysphagia. Oelschlager and associates14 demonstrated that extending the myotomy 3 cm distally to the externally visualized gastroesophageal junction reduces postoperative pressures on the lower esophageal sphincter (LES) with no significant difference in reflux when this is combined with an antireflux procedure. They did not utilize intraoperative endoscopy to assess the gastric extent of the standard myotomy. However, they noted that a standard myotomy (1.5 cm) onto the cardia with Dor fundoplication is associated with higher postoperative LES pressure and dysphagia and no significant difference in postoperative reflux when compared to an extended myotomy combined with a Toupet fundoplication. They also noted that reintervention for dysphagia is more frequent with standard myotomy.

Surgical therapy for achalasia remains a balance between relief of dysphagia and destruction of the antireflux barrier.4 An evaluation of the utility of intraoperative endoscopy during Heller myotomy by Alves et al.1 found that “endoscopic and lap- aroscopic criteria for gastroesophageal junction identification were discordant in 58% of patients.” They found that the gastro- esophageal junction identified by endoscopy is more distal than it is by laparoscopic identification. Intraoperative endoscopy allows for precise division of the lower esophageal sphincter and a more accurate assessment for the complication of esophageal perforation. In addition, comparison of the intraoperative pre- and postmyotomy state allows the surgeon to assess the patency and the distensibility of the LES by air insufflation and by the impedance to the passage of the endoscope through the LES. Measurement of the mucosal bulge through the myotomy provides a further assessment of the myotomy, so that relief of dysphagia is balanced against gastroesophageal reflux; this should therefore be considered a “targeted” myotomy.

Intraoperative manometry during myotomy corroborates the inability of laparoscopy to delineate the gastroesophageal junction precisely. Chapman et al.5 found that 47% of patients who underwent intraoperative manometry had a high residual pressure zone requiring extension of the myotomy. Despite the potential for decreasing the incidence of an incomplete myotomy, they state that intraoperative manometry “requires a level of expertise that may not be available in many institutions.” In addition, manometry does not seem to improve the effectiveness of endoscopic confirmation significantly. Therefore the myotomy should be assessed for completeness both endoscopically and laparoscopically.

One of the problems noted by Ellis7 was the obligate reflux produced by a long myotomy, necessitating a fundoplication in a patient with poor esophageal body motility and thus adding to complaints of postoperative dysphagia. Although a classic Nissen fundoplication carries a high rate of obstruction, the addition of a Dor fundoplication to laparoscopic myotomy reduces the risk of pathologic gastroesophageal risk ninefold, with less alteration of the anatomic barriers to reflux.16 An anterior fundoplication also buttresses the exposed esophageal mucosa and protects against a delayed thermal mucosal injury and leak. Toupet fundoplication requires posterior dissection of the esophagus, greater disruption of the angle of His, and anterior displacement of the esophagogastric junction, which theoretically may lead to gastroesophageal reflux. Dor anterior fundoplication combined with endoscopic visualization of the adequacy of the targeted laparoscopic myotomy are the pillars of the authors’ operative strategy for achalasia.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree