12

CHAPTER

![]()

Miscellaneous Nodules, Depositions, and Cysts

This chapter includes a number of miscellaneous, largely unrelated conditions. Most share the radiographic finding of a parenchymal nodule or nodules, whereas some are linked in that they represent unusual parenchymal depositions. Blebs, bulla, other cysts, and pneumothorax-related changes are also included for lack of a more appropriate place to describe them.

TOPICS

Miscellaneous Nodules

Miscellaneous Nodules

Pulmonary Hyalinizing Granuloma (PHG)/Fibrosing Mediastinitis (FM)

Pulmonary Hyalinizing Granuloma (PHG)/Fibrosing Mediastinitis (FM)

Amyloid Nodule (Nodular Amyloidosis)

Amyloid Nodule (Nodular Amyloidosis)

Nodular Lymphoid Hyperplasia/Inflammatory Pseudotumor

Nodular Lymphoid Hyperplasia/Inflammatory Pseudotumor

Intraparenchymal Lymph Node

Intraparenchymal Lymph Node

Pulmonary Infarct

Pulmonary Infarct

Round Atelectasis

Round Atelectasis

Pulmonary Apical Cap

Pulmonary Apical Cap

Miscellaneous Depositions

Miscellaneous Depositions

Alveolar Septal Amyloidosis

Alveolar Septal Amyloidosis

Metastatic Calcification

Metastatic Calcification

Metaplastic Ossification

Metaplastic Ossification

Blebs, Bullae, Other Cysts, and Pneumothorax-Related Changes

Blebs, Bullae, Other Cysts, and Pneumothorax-Related Changes

PULMONARY HYALINIZING GRANULOMA (PHG)/FIBROSING MEDIASTINITIS (FM)

Pulmonary hyalinizing granuloma (PHG) and fibrosing mediastinitis (FM) are included together because their histologic findings and pathogenesis are identical. They differ only by site with PHG being confined to the lung parenchyma and FM affecting mainly mediastinal structures although it can extend into the lung causing the appearance of a lung mass.

Histologic Features

Thick, keloid-like, collagen bundles that in the lungs form discrete nodules and in the mediastinum infiltrate and replace soft tissue

Thick, keloid-like, collagen bundles that in the lungs form discrete nodules and in the mediastinum infiltrate and replace soft tissue

Variable admixed chronic inflammatory cell infiltrate between the collagen bundles

Variable admixed chronic inflammatory cell infiltrate between the collagen bundles

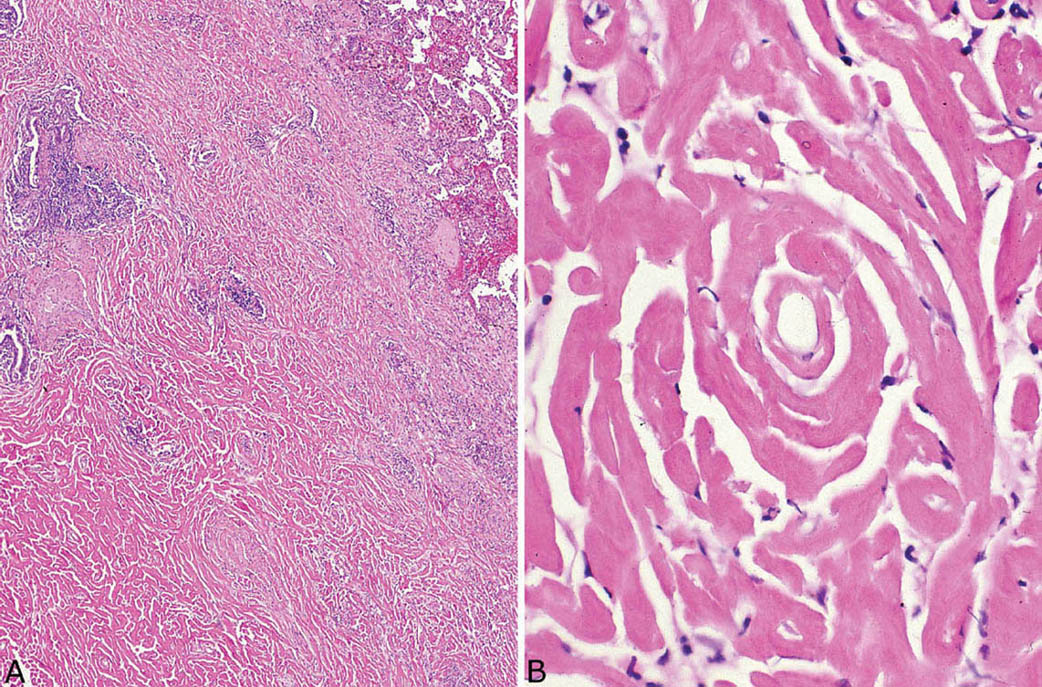

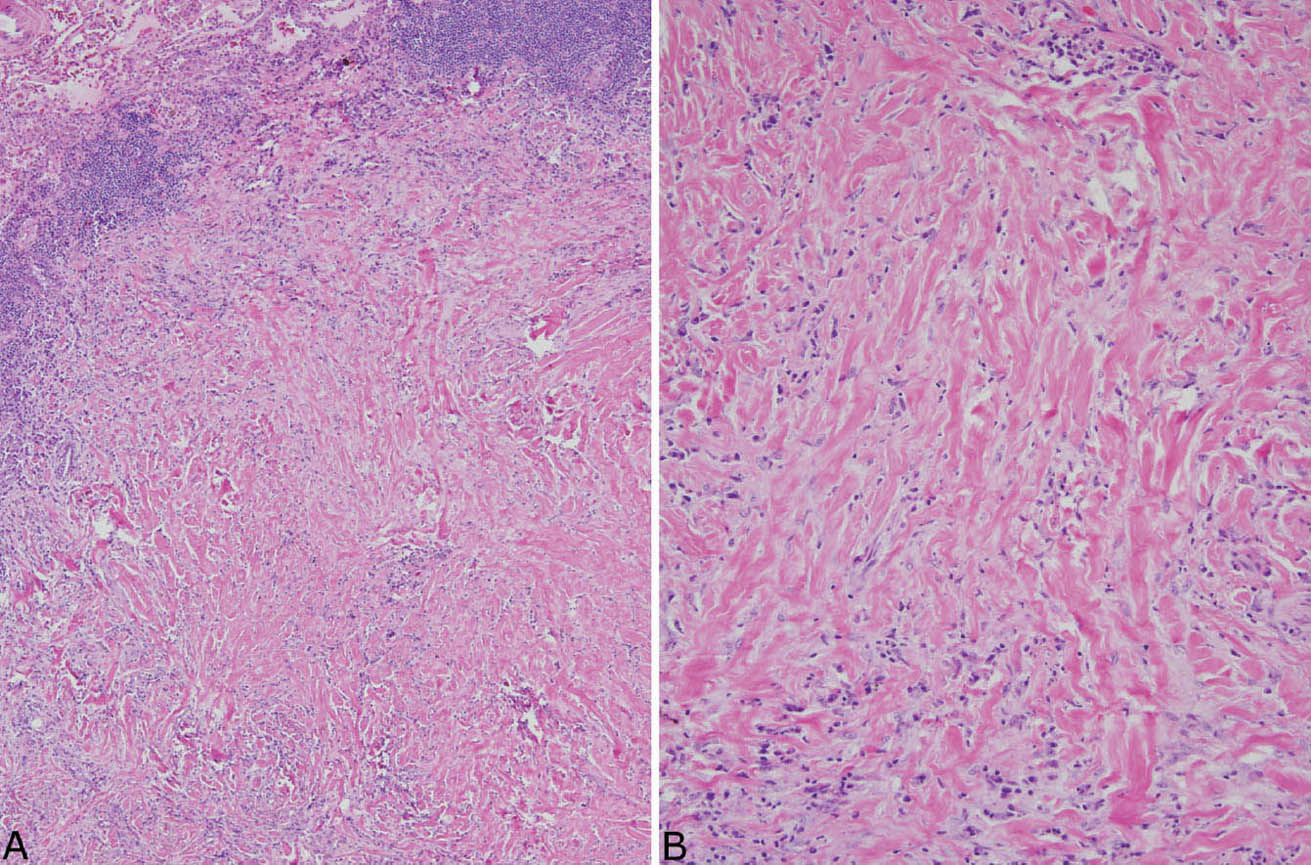

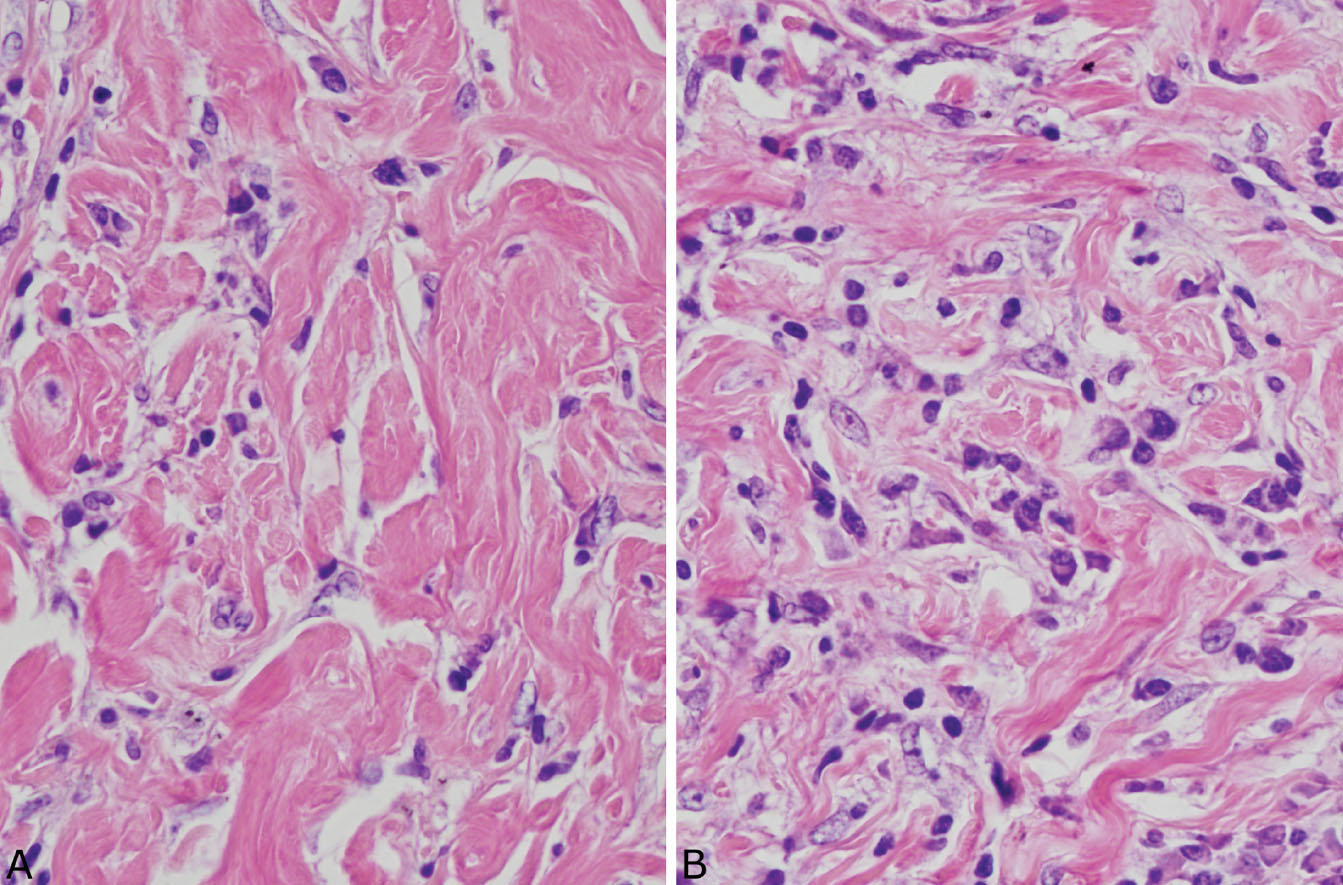

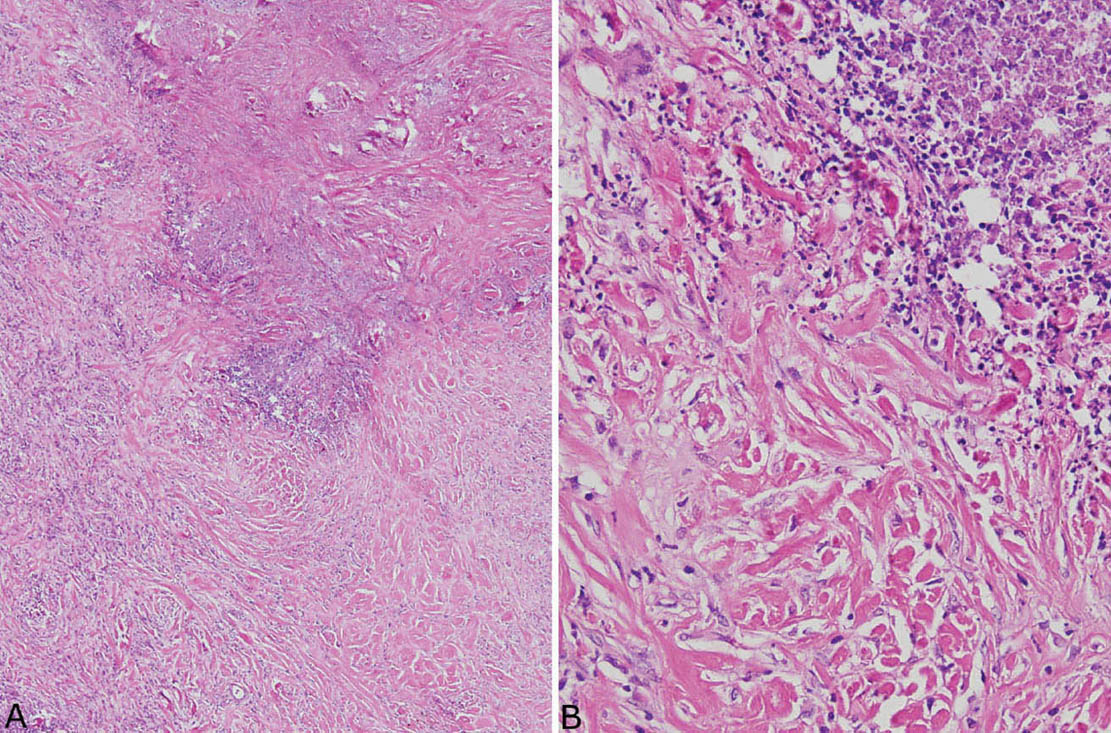

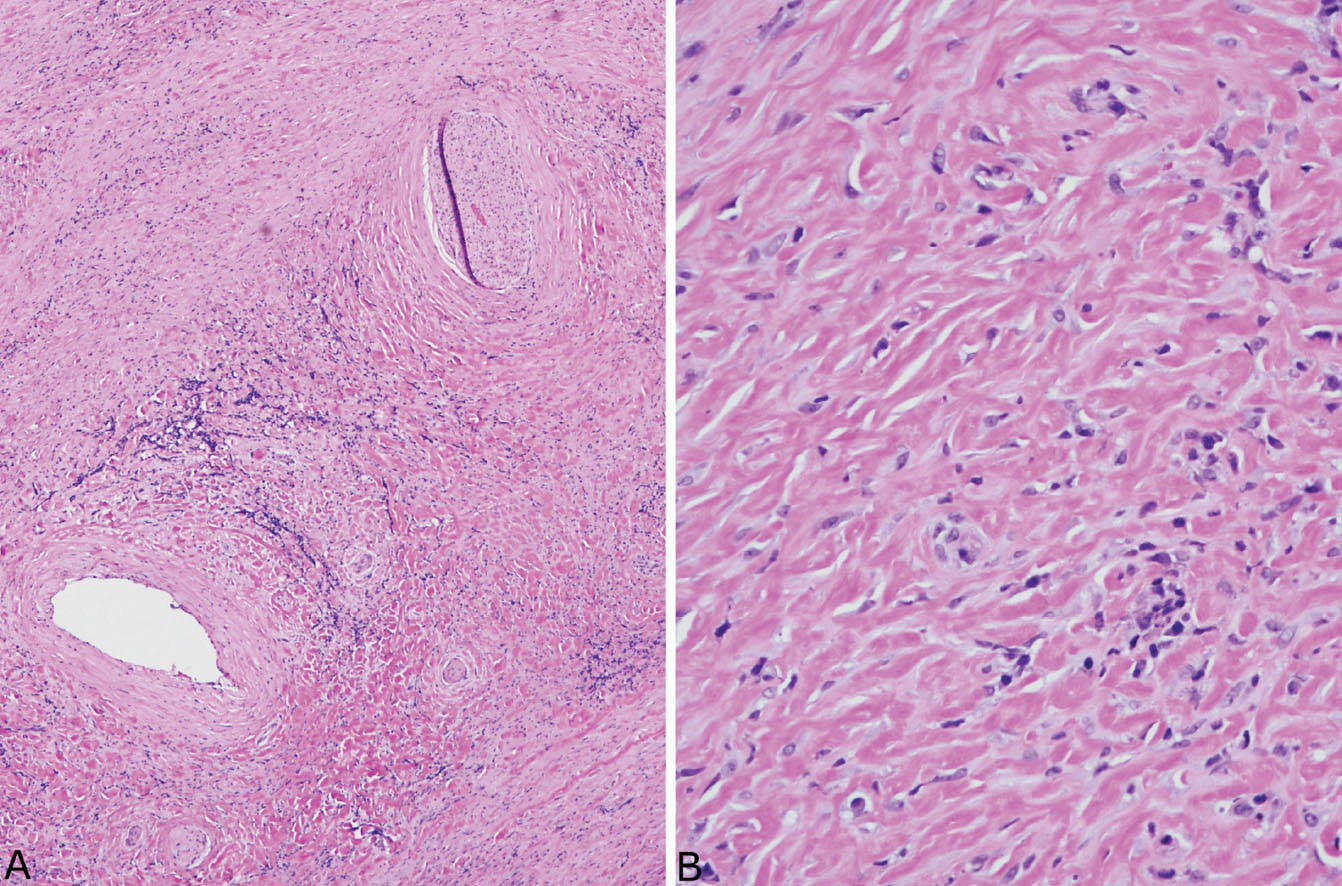

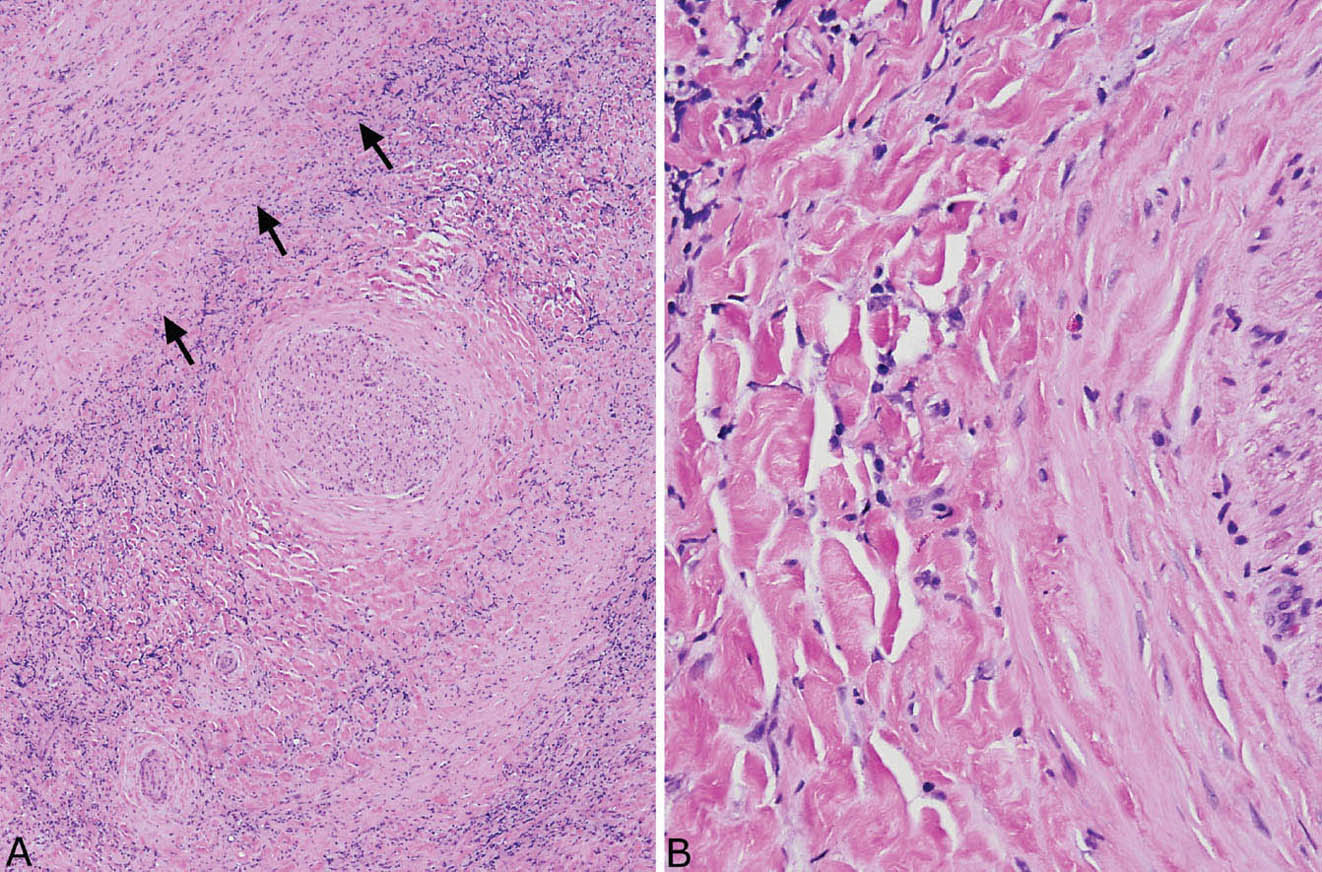

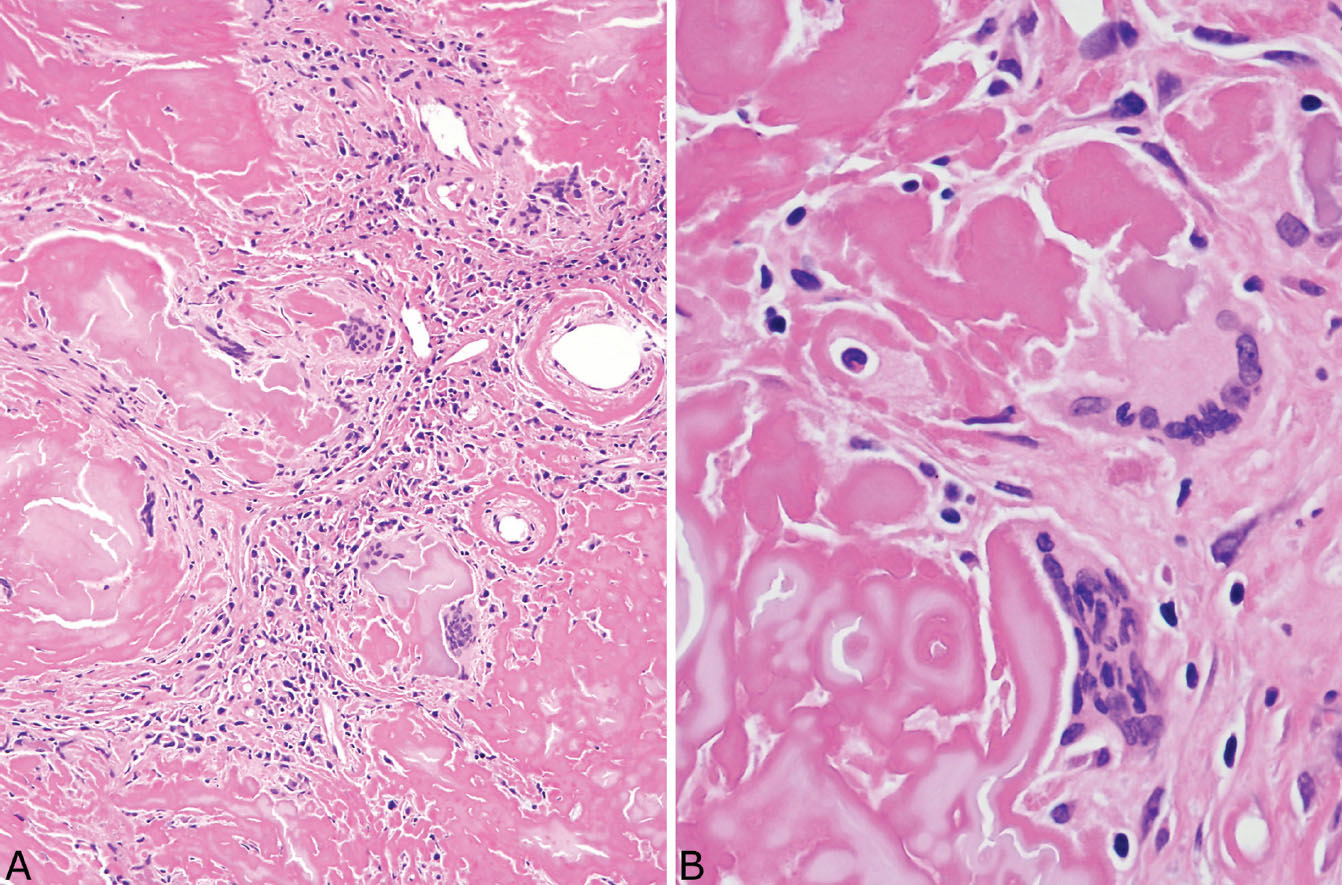

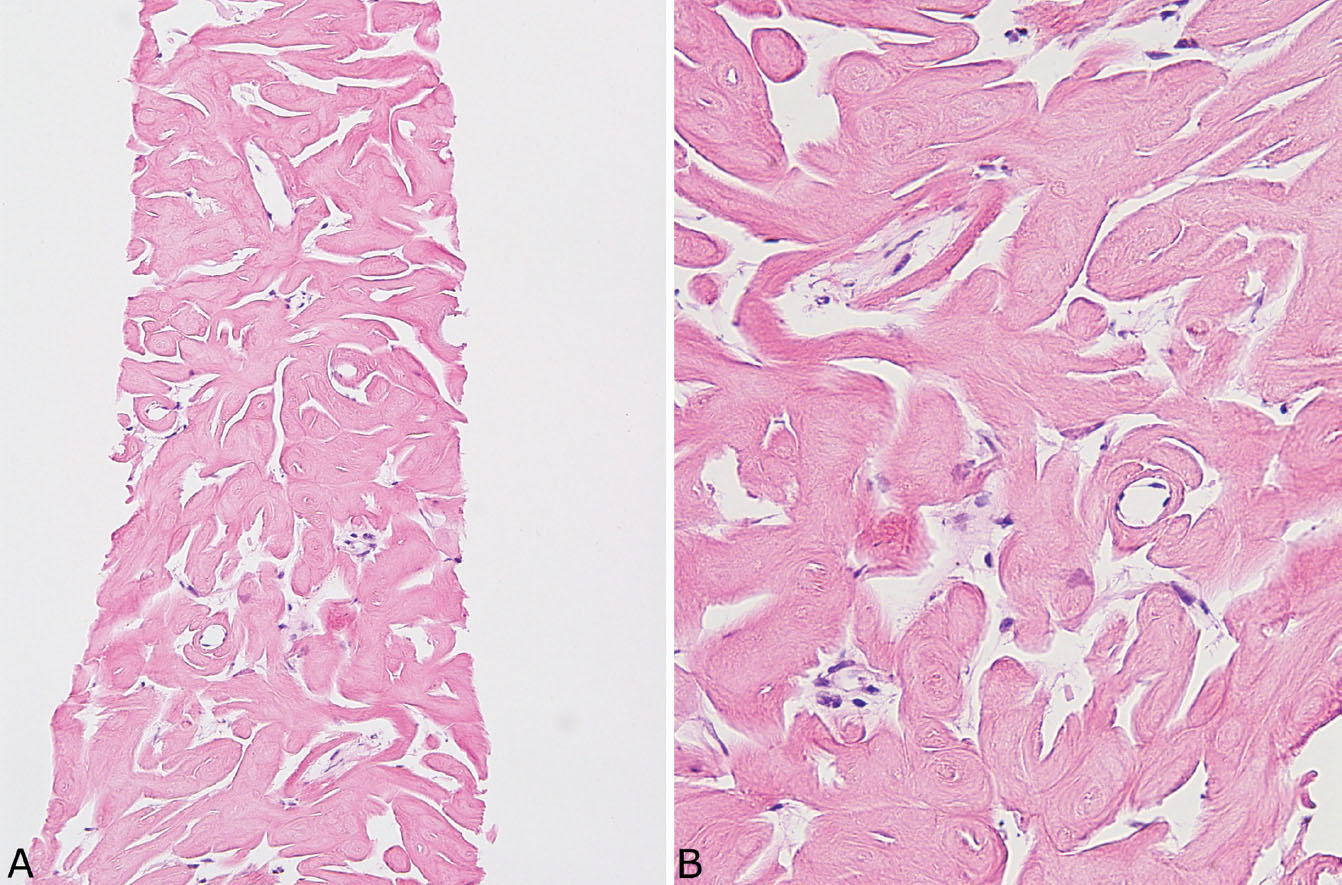

The histologic hallmark of PHG is nodular replacement of portions of lung parenchyma by thick, deeply eosinophilic collagen bundles reminiscent of the collagen characteristic of keloid type scars (Figures 12.1 and 12.2). The nodules are well demarcated from adjacent lung parenchyma. The collagen bundles are haphazardly arranged in the nodules, but typically have a lamellar pattern often forming cartwheels or whorls around blood vessels. Variable chronic inflammation including mainly lymphocytes and plasma cells is interspersed between the collagen bundles with some lesions appearing almost acellular and others containing a prominent chronic inflammatory cell infiltrate (Figure 12.3). Often chronic inflammation is most striking at the interface of the lesion with normal lung. Large numbers of CD20-positive B-lymphocytes may be present in the infiltrate and should not be interpreted as evidence of lymphoma. Occasionally, foci of necrosis are present within PHG, and are thought to be ischemic in nature (Figure 12.4), but giant cells and granulomatous inflammation are not features. Calcification is usually absent. Spurious weak or equivocal Congo red staining has been reported in PHG, and should be considered negative in the absence of strong staining.

FIGURE 12.1 Pulmonary hyalinizing granuloma. (A) At low magnification, a well-circumscribed (normal lung at top right) solid nodule is seen that is mostly acellular except for scattered foci of chronic inflammation. (B) A higher magnification illustrates the characteristic thick keloid-like collagen bundles that comprise most of the nodule and are arranged in a lamellar configuration.

FIGURE 12.2 Pulmonary hyalinizing granuloma. (A) In this example, inflammation is more prominent than in Figure 12.1. The lesion is well demarcated from normal lung (top left), and significant chronic inflammation is present, especially at the edge. (B) A higher magnification shows the chronic inflammatory cell infiltrate between the characteristic thick, eosinophilic collagen bundles.

FIGURE 12.3 Variable inflammation in pulmonary hyalinizing granuloma. (A) In this field, the characteristic collagen bundles predominate with minimal inflammation. (B) In this field, numerous plasma cells and scattered lymphocytes are seen between the collagen bundles.

In the mediastinum, the process is characterized by the same type of collagen deposition with varying amounts of associated chronic inflammation as occurs in PHG (Figure 12.5), but there are some minor differences. FM is an infiltrative process that surrounds and compresses mediastinal structures, including blood vessels, nerves, and occasionally bronchi rather than being well circumscribed like PHG (Figure 12.6). Unlike PHG, necrotizing granulomatous inflammation may be admixed with the areas of FM (so-called granulo-matous mediastinitis), and foci of calcification may be present. Rarely, organisms, usually histoplasma, can be found in the necrotizing granulomas using special stains, but organisms cannot be identified in the collagenous areas. As in PHG, large numbers of CD20-positive B-lymphocytes may be associated with the process and should not be concerning for lymphoma.

Differential Diagnosis

The main lesions in the differential diagnosis of PHG include amyloid nodules, which are discussed in the subsequent section, “Amyloid Nodule” (see also Table 12.1 for distinguishing features), and old, “burned out” infectious granulomas. Old infectious granulomas usually contain central granular eosinophilic necrosis with variable and often prominent calcification. Although they may show hyalinized rather than necrotic centers, the keloid type of collagen deposition, characteristic of PHG, is not a feature. Rather, a uniform deposition of collagen lacking distinct individual collagen bundles is present. Usually, there is also some remnant of granulomatous inflammation with at least scattered epithelioid histiocytes or multinucleated giant cells surrounding the central portion. Although collagen bundles may be prominent at the periphery, they usually comprise a thin layer with an orderly concentric arrangement that contrasts with the thick layer of haphazard and whorled collagen bundles in PHG.

Inflammatory myofibroblastic tumor (previously known as plasma cell granuloma) is often included in the differential diagnosis of PHG. However, this lesion is quite different with fibroblasts and plasma cells predominating. Keloid-like collagen fibers are not a feature. The distinction of these two lesions is usually not a problem.

Similarly, there are few lesions in the differential diagnosis of FM. Because dense fibrosis may occur as a reactive process around other lesions, however, the main issue is to make certain that the biopsy is representative. Hodgkin disease, especially, can have associated hyalinized fibrosis, although usually without keloid-like collagen bundles, and large paucicellular fibrotic areas may be present. Multiple slides should be examined, therefore, to look for atypia in the cellular infiltrate. Other lymphomas, such as primary mediastinal large B-cell, may also have fibrosis, but usually the fibrosis is interspersed with a prominent atypical lymphoid infiltrate. In any case, the surgeon should be urged to take a deep biopsy of a mediastinal mass rather than sampling only the edge. Knowledge of the clinical and radiographic findings should help in the differential diagnosis as well. It is important to remember, however, that CD20-positive B-cells may outnumber CD3-positive lymphocytes in FM, and this finding in the absence of morphologically atypical lymphocytes should not be considered indicative of lymphoma.

FIGURE 12.4 Necrosis in pulmonary hyalinizing granuloma. (A) At low magnification, an irregular area of necrosis is seen within the collagenous background otherwise typical of PHG. (B) At high magnification, nuclear debris is prominent within the necrotic zone. Note the abrupt transition to the characteristic thick collagen bundles without evidence of a granulomatous or other inflammatory reaction. PHG, pulmonary hyalinizing granuloma.

FIGURE 12.5 Fibrosing mediastinitis. (A) At low magnification, a dense fibroinflammatory process replaces soft tissue, surrounds a nerve (top right), and narrows an artery (bottom left). (B) A higher magnification shows the characteristic closely packed thick, keloid-like collagen bundles with scattered intermingled chronic inflammatory cells.

FIGURE 12.6 Fibrosing mediastinitis. (A) Chronic inflammation is prominent in this area of dense fibrosis. A large nerve (center) is surrounded by the fibroinflammatory process, and a large vein (top left, arrows outline the wall) is obliterated. (B) At high magnification, the typical keloid-like collagen bundles are seen surrounding the nerve (right).

TABLE 12.1 Distinguishing Features of Amyloid Nodule and Pulmonary Hyalinizing Granuloma

Amyloid Nodule | Pulmonary Hyalinizing Granuloma |

Globular, irregular deposits of amyloid which appear amorphous, glassy at high magnification | Thick collagen bundles arranged in parallel which appear fibrillary at high magnification |

Foreign-body giant cells engulfing amyloid common | Foreign-body giant cells not a feature |

Variable chronic inflammation replacing areas of amyloid deposition | Variable chronic inflammation interspersed between collagen bundles |

Calcification, ossification often present | Calcification, ossification usually not present |

Congo red stain usually positive | Congo red stain usually negative |

Some cases of PHG and FM have been reported to contain increased numbers of IgG4 plasma cells, and a relationship to idiopathic IgG4-related sclerosing disease has been proposed. Caution should be exercised in diagnosing IgG4-related diseases based mainly on increased numbers of IgG4 plasma cells, however, as increased IgG4 plasma cells may be a nonspecific finding in a wide variety of unrelated inflammatory conditions. The diagnosis of IgG4-related disease requires evidence of venulitis usually with scattered eosinophils in addition to fibrosis and numerous IgG4-positive plasma cells, and serum IgG4 levels should be elevated. Rare cases of FM have been associated with fibroinflammatory processes in extrathoracic locations, including retroperitoneal fibrosis and periorbital fibrosis, and these cases may represent veritable examples of IgG4 disease. It is important to identify IgG4 disease, as the process may respond to corticosteroid therapy.

Clinical Features

PHG is quite rare. It usually occurs in young- to middle-aged adults with mild presenting symptoms including cough, fatigue, and fever. About one quarter of patients are asymptomatic. Various autoimmune phenomena have been reported, including positive antinuclear antibody (ANA), rheumatoid factor, anti-smooth muscle antibody, and Coombs-positive hemolytic anemia. Radiographically, multiple bilateral nodular densities are the most common finding, although solitary nodules are sometimes seen. The prognosis is good, although the lesions may enlarge over time.

FM is also uncommon, but is seen more often than PHG. Like PHG, it preferentially affects young and middle-aged adults. Symptoms, however, are usually related to compression of mediastinal structures, and include most commonly cough, dyspnea, and hemoptysis, although some patients are asymptomatic. Mediastinal widening or mass formation often involving the right paratracheal, subcarinal, or hilar regions is characteristic radiographically. Narrowing or obstruction of blood vessels or bronchi may be seen on CT examination, and calcification may be present. The prognosis is good when the lesion is localized, but is guarded when vital structures are infiltrated. Surgical intervention and stenting may be beneficial, but there is little evidence supporting corticosteroid, antifungal, or other medical therapy.

The pathogenesis of PHG and FM is thought to be related in most cases to an abnormal immune reaction to a prior infection, usually histoplasmosis or less often tuberculosis.

Helpful Tips—PHG/FM

Increased numbers of CD20-positive B-lymphocytes may be present in PHG and FM, and are not indicative of lymphoma in the absence of cytologic atypia.

Increased numbers of CD20-positive B-lymphocytes may be present in PHG and FM, and are not indicative of lymphoma in the absence of cytologic atypia.

Do not overinterpret weakly or equivocally positive Congo red stains in PHG as indicating amyloid deposition; use other features (Table 12.1) to confirm the diagnosis.

Do not overinterpret weakly or equivocally positive Congo red stains in PHG as indicating amyloid deposition; use other features (Table 12.1) to confirm the diagnosis.

Do not diagnose old, “burned out” infectious granulomas as “hyalinized granuloma,” as that diagnosis may cause confusion clinically with the specific entity of PHG.

Do not diagnose old, “burned out” infectious granulomas as “hyalinized granuloma,” as that diagnosis may cause confusion clinically with the specific entity of PHG.

Make certain that a mediastinal biopsy is representative and not just from the fibrotic periphery of another lesion before diagnosing FM.

Make certain that a mediastinal biopsy is representative and not just from the fibrotic periphery of another lesion before diagnosing FM.

When plasma cells are prominent, perform immunostaining for IgG4, and, if positive, suggest additional clinical evaluation for idiopathic IgG4-related disease.

When plasma cells are prominent, perform immunostaining for IgG4, and, if positive, suggest additional clinical evaluation for idiopathic IgG4-related disease.

AMYLOID NODULE (NODULAR AMYLOIDOSIS)

Amyloid deposition in the lung occurs in three main forms: nodular amyloidosis, diffuse alveolar septal amyloidosis, and tracheobronchial amyloidosis. Tracheobronchial amyloidosis is discussed in Chapter 11, and alveolar septal amyloidosis is described in the subsequent section, “Alveolar Septal Amyloidosis.”

Histologic Features

Nodular replacement of lung parenchyma by amorphous, eosinophilic amyloid deposition

Nodular replacement of lung parenchyma by amorphous, eosinophilic amyloid deposition

Frequent foreign-body giant cell reaction, calcification, ossification, and/or chronic inflammation associated with the amyloid

Frequent foreign-body giant cell reaction, calcification, ossification, and/or chronic inflammation associated with the amyloid

Variable numbers of plasma cells that may be monoclonal

Variable numbers of plasma cells that may be monoclonal

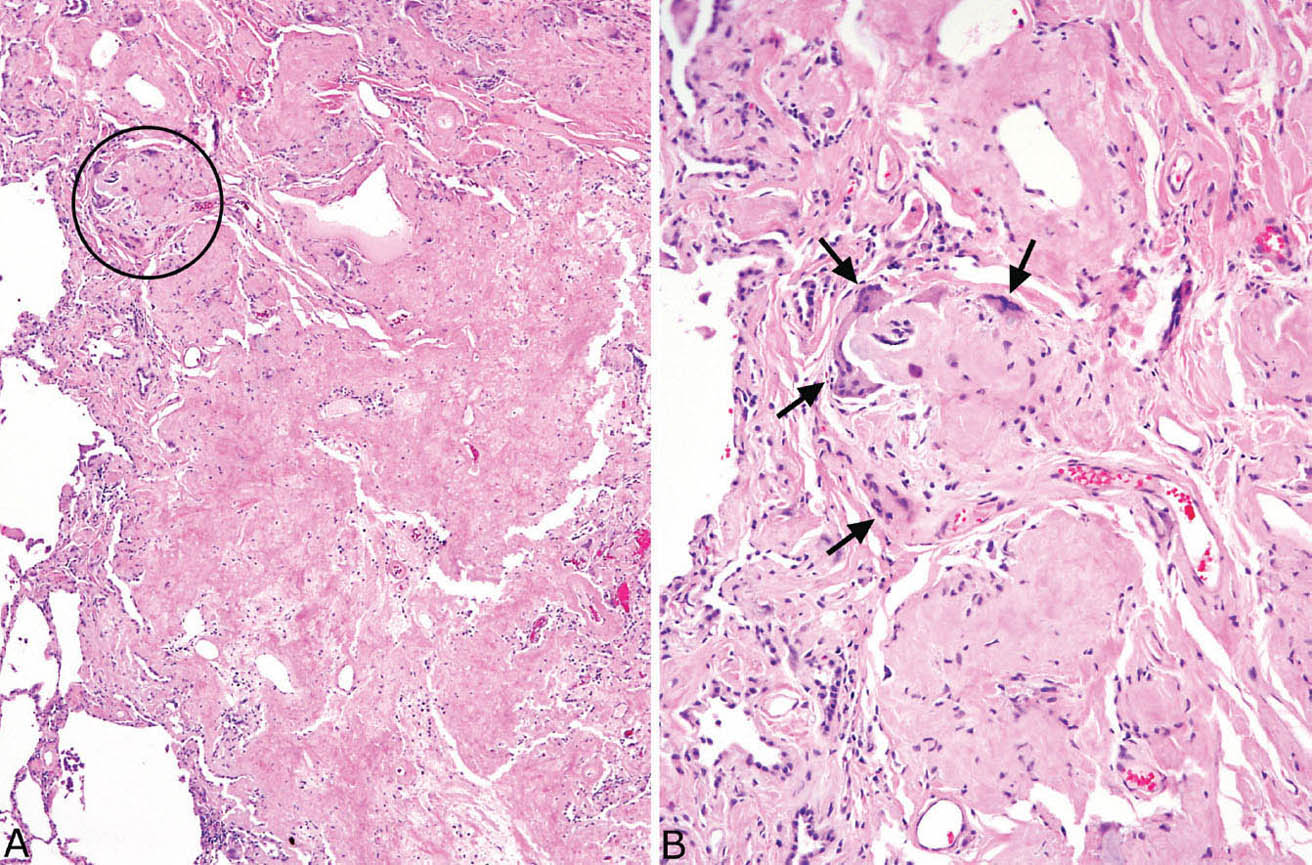

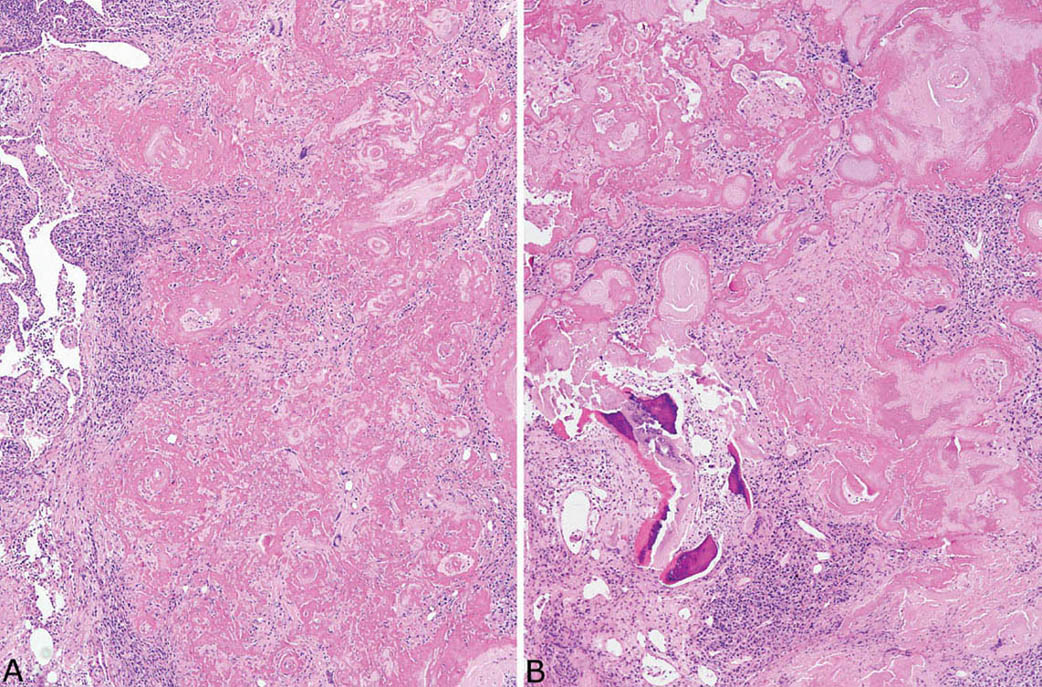

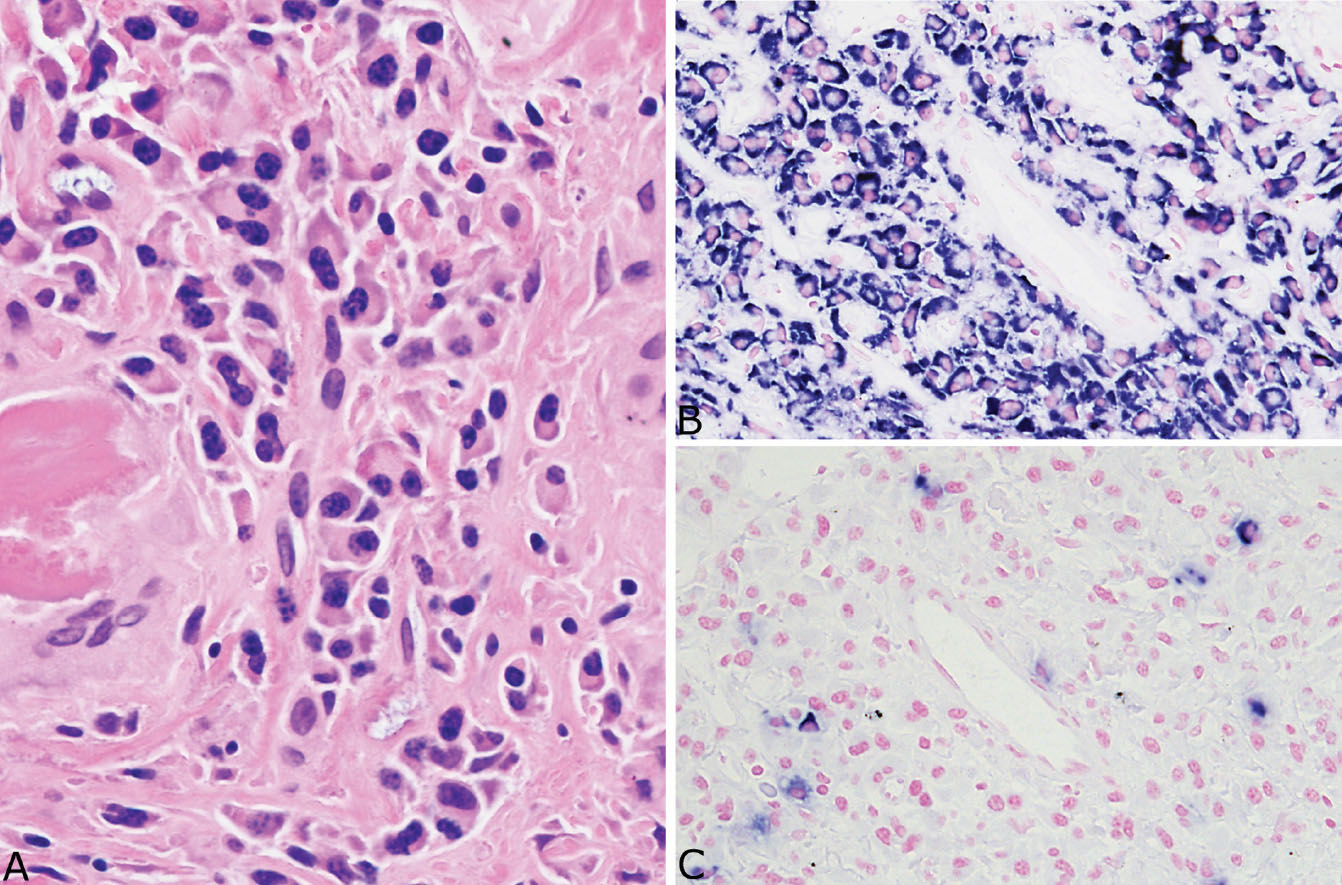

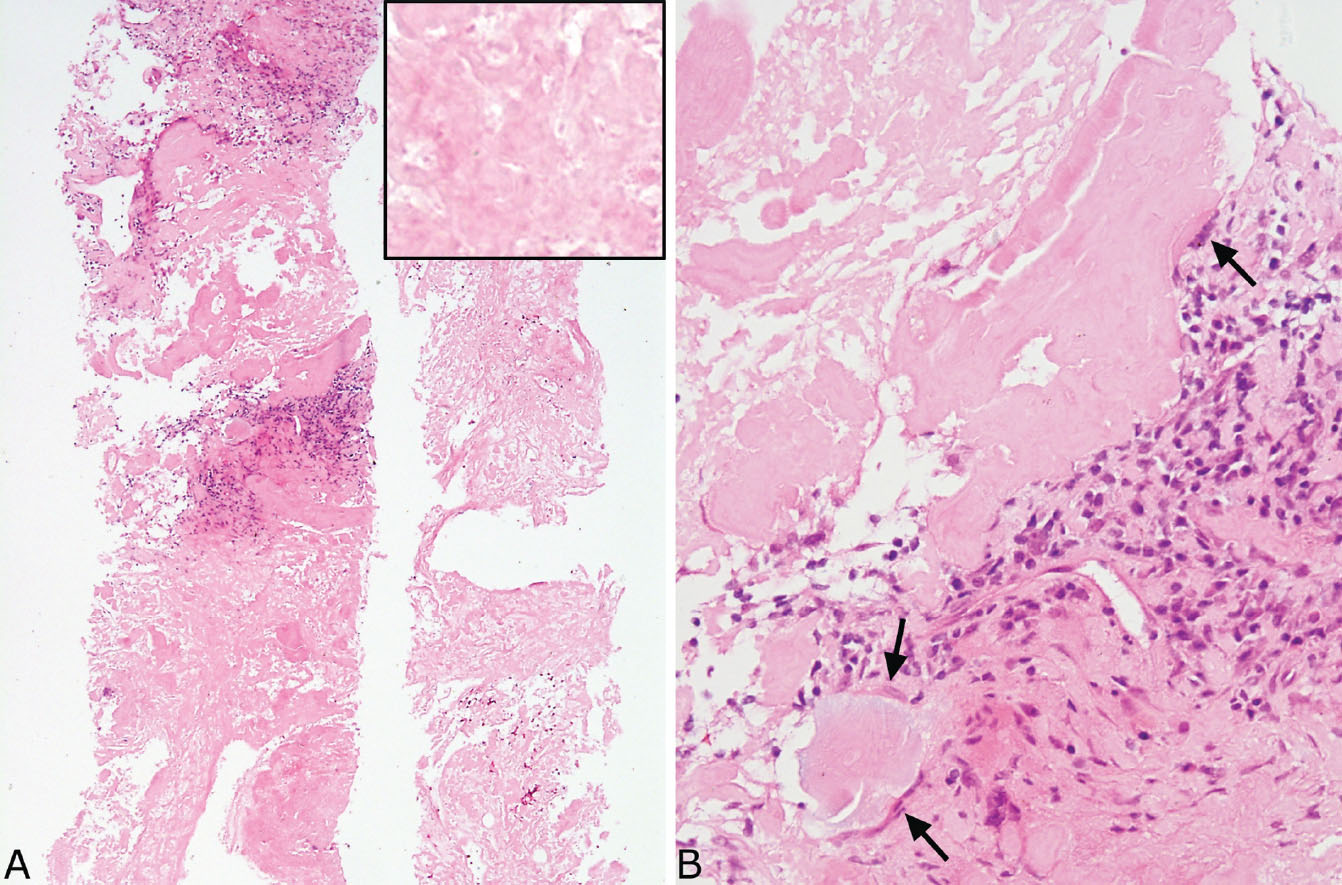

Nodular amyloidosis is characterized by localized deposition of eosinophilic, amorphous amyloid that replaces portions of lung parenchyma (Figures 12.7 and 12.8). The resultant nodules are unencapsulated but well demarcated from surrounding lung parenchyma. A foreign-body giant cell reaction engulfing amyloid is commonly present and usually visible at low magnification (Figure 12.9). Amyloid deposition is seen within blood vessel walls in the nodule and occasionally in parenchyma immediately adjacent to the nodule, but usually not in more distant parenchyma. Areas of calcification, ossification, and occasionally cartilage formation are common, and there may be a variable associated chronic inflammatory cell infiltrate. In some cases, clusters of plasma cells are seen, and staining for kappa and lambda light chains may show monoclonality (Figure 12.10). This finding, by itself, does not indicate a systemic plasma cell dyscrasia, but should stimulate additional clinical evaluation in this regard. Some consider amyloid nodules to belong in the spectrum of mucosa-associated lymphoid tissue (MALT) lymphomas.

FIGURE 12.7 Amyloid nodule. (A) A portion of lung is replaced by amorphous eosinophilic material that is well demarcated from the adjacent lung (left). The circled area is shown at higher magnification in B where a foreign-body giant cell reaction (arrows) is seen surrounding the amorphous, glassy amyloid.

FIGURE 12.8 Amyloid nodule. (A) In this example, clusters of chronic inflammatory cells are prominent, and numerous multinucleated giant cells are visible within the amyloid deposits even at low magnification. (B) In addition to chronic inflammation, areas of ossification are seen in this case.

FIGURE 12.9 Foreign-body giant cell reaction in amyloid nodule. (A) In this area, numerous multinucleated giant cells surround amyloid deposits, and there is also an associated prominent chronic inflammatory cell infiltrate. (B) A higher magnification shows the multinucleated giant cells engulfing the amyloid, a finding that helps to confirm the diagnosis in difficult cases.

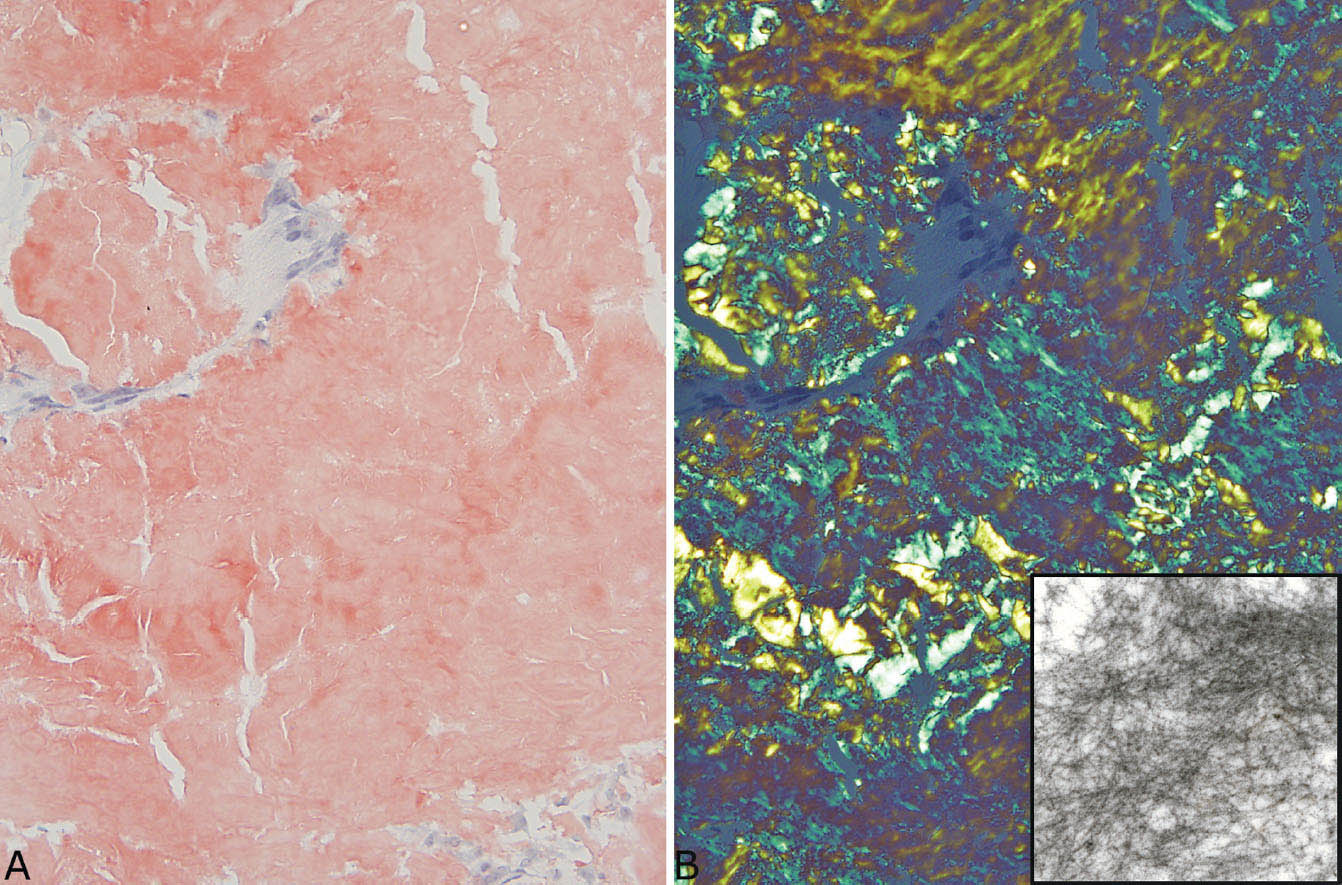

Usually, the diagnosis of amyloid is clear-cut in hematoxylin and eosin (H and E) stains, but additional studies can be performed if necessary. Apple green staining with Congo red under polarized light is characteristic, but not always reliable (Figure 12.11; see also Figures 12.26B and 12.27A). Immunohistochemical staining for amyloid proteins may help as well, but also is not entirely specific and may be difficult to interpret (see Figure 12.27B). In cases with equivocal staining characteristics, electron microscopy can be used and should show the characteristic haphazardly arranged thin amyloid fibrils (Figure 12.11, inset). Liquid chromatography and tandem mass spectrophotometry have been used to subtype the amyloid.

Occasionally, a nodule will contain all the characteristic H and E features of amyloid nodules, but will fail to stain appropriately with Congo red or amyloid immunostains, and amyloid fibrils cannot be identified by electron microscopy. Such lesions have been termed “amyloid-like nodules.” Some cases represent manifestations of light chain deposition disease and this condition should be excluded clinically. Light chain deposition disease often is associated with plasma cell myeloma, and renal involvement may be prominent. Some amyloid-like nodules are not associated with an underlying disease and are of uncertain histogenesis.

Differential Diagnosis

The main lesion in the differential diagnosis of amyloid (and amyloid-like) nodules is PHG, and their contrasting features are listed in Table 12.1. At low magnification, the thick, relatively uniform collagen bundles arranged in parallel that are characteristic of PHG (see Figures 12.1–12.3) differ from the irregular clumps of amorphous amyloid that are often also found in blood vessel walls. The frequent presence of foreign-body giant cells engulfing amyloid in amyloid nodules is another strong clue to diagnosis, as foreign-body giant cells are not seen in PHG. Although chronic inflammation may be present in both, it is usually interspersed between intact collagen bundles in PHG rather than forming irregular clusters that replace portions of amyloid. Areas of calcification and ossification are common in amyloid nodules but are usually not seen in PHG. At higher magnification, the fibrillary composition of the collagen bundles contrasts with the amorphous glassy appearance of amyloid. Congo red stains, of course, are helpful, but need to be interpreted with caution because false weakly positive or equivocal staining may occur occasionally in PHG. The diagnosis can be especially challenging in small biopsy specimens, but with careful attention to detail the correct diagnosis can be established (compare Figures 12.12 and 12.13).

FIGURE 12.10 Plasma cells in amyloid nodules. (A) A small cluster of reactive appearing monoclonal plasma cells is present in this example from an asymptomatic 91-year-old woman with no evidence of systemic disease. The plasma cells are almost all (B) positive for kappa light chains while (C) negative for lambda light chains. Monoclonality in this setting does not necessarily indicate a systemic plasma cell dyscrasia, but should prompt additional clinical evaluation.

FIGURE 12.11 Congo red staining in amyloid nodule. (A) Congo red stain under ordinary light showing the typical orange-red appearance. (B) Under polarized light, the characteristic apple-green color is seen. The inset is an electron micrograph showing the haphazardly arranged thin fibers of amyloid.

Clinical Features

Amyloid nodules usually occur as isolated lung lesions and are generally not associated with amyloid deposition in other organs, although rare cases have been reported in association with amyloid skin lesions. Patients are usually asymptomatic or have mild chest complaints. Underlying collagen vascular diseases are common, especially Sjogren syndrome, and a few patients have a history of low-grade MALT lymphoma. Solitary or multiple well-circumscribed masses are seen radiographically, and biopsy or excision is usually performed to exclude a malignant neoplasm.

Helpful Tips—Amyloid Nodules

A foreign-body giant cell reaction to the amyloid deposits is a helpful clue in routine stains to confirm amyloid; finding amyloid deposits within blood vessel walls also helps confirm the diagnosis.

A foreign-body giant cell reaction to the amyloid deposits is a helpful clue in routine stains to confirm amyloid; finding amyloid deposits within blood vessel walls also helps confirm the diagnosis.

The presence of monoclonal plasma cells within an amyloid nodule is common; it does not necessarily indicate a systemic plasma cell dyscrasia, but should stimulate additional clinical evaluation.

The presence of monoclonal plasma cells within an amyloid nodule is common; it does not necessarily indicate a systemic plasma cell dyscrasia, but should stimulate additional clinical evaluation.

NODULAR LYMPHOID HYPERPLASIA/INFLAMMATORY PSEUDOTUMOR

The terms nodular lymphoid hyperplasia and inflammatory pseudotumor can be used interchangeably, although nodular lymphoid hyperplasia is the preferred term. Although descriptively correct, inflammatory pseudotumor has been used indiscriminately in the past for a number of unrelated inflammatory and neoplastic lesions, and it may be best to use the term parenthetically with nodular lymphoid hyperplasia.

FIGURE 12.12 Needle biopsy of amyloid nodule. (A) At low magnification, this biopsy is composed entirely of eosinophilic material with focal interspersed chronic inflammation that has replaced lung parenchyma. The inset is a higher magnification showing the amorphous, glassy appearance. (B) Focally, at higher magnification, a foreign-body giant cell reaction (arrows) is seen surrounding the amyloid, a finding that helps to confirm the diagnosis.

FIGURE 12.13 Needle biopsy of pulmonary hyalinizing granuloma. (A) At low magnification, thick eosinophilic cords arranged in parallel replace lung parenchyma. (B) At higher magnification, the fibrillary appearance of the collagen bundles contrasts with the amorphous, glassy appearance of amyloid (compare with Figure 12.12).

Histologic Features

Well-circumscribed nodule composed of a variable mixture of chronic inflammation and fibrosis

Well-circumscribed nodule composed of a variable mixture of chronic inflammation and fibrosis

Lymphoid follicles with reactive germinal centers usually prominent

Lymphoid follicles with reactive germinal centers usually prominent

Areas of dense fibrosis with scarring usually present within the infiltrate

Areas of dense fibrosis with scarring usually present within the infiltrate

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree