Mesenteric Ischemic Syndromes

Intestinal ischemia comprises a small portion of all peripheral vascular problems. Although aortic atherosclerosis may involve the origins of the mesenteric arteries, intestinal collateral blood flow usually is adequate enough to prevent symptomatic, chronic intestinal ischemia. Likewise, arterial emboli can obstruct mesenteric arteries, but more commonly they flow by the visceral vessels and lodge in the leg arteries. Consequently, these anatomic and hemodynamic features make intestinal ischemia less common than chronic claudication or acute ischemia of the lower extremities.

For several reasons, acute or chronic intestinal ischemia remains one of the most challenging problems of peripheral vascular surgery. Diagnosis is frequently entertained based upon clinical suspicion or a lack of other clear etiology for the patient’s problems. It is not unusual for someone who has complained of nonspecific abdominal pain to have had a detailed evaluation of their gastrointestinal tract, and yet be referred for consideration of arterial insufficiency very late in their course. Failure to recognize that a patient has some form of intestinal ischemia is one of the main reasons for poor results obtained with intervention. Patients often are operated on too late to salvage the ischemic intestine or, many times, to save the patient’s life. Even when intestinal ischemia is recognized and treated expeditiously, many patients still succumb because of serious underlying medical problems. The best surgical results have been achieved in patients with chronic intestinal angina who undergo intestinal revascularization before severe weight loss or acute thrombosis occurs.

In this chapter, we emphasize early recognition of intestinal ischemia. Delay in diagnosis represents one of the primary failings in the care of these patients. Also, we highlight features of treatment and some of the decision making needed in the proper care of these patients.

MESENTERIC ARTERY ANATOMY

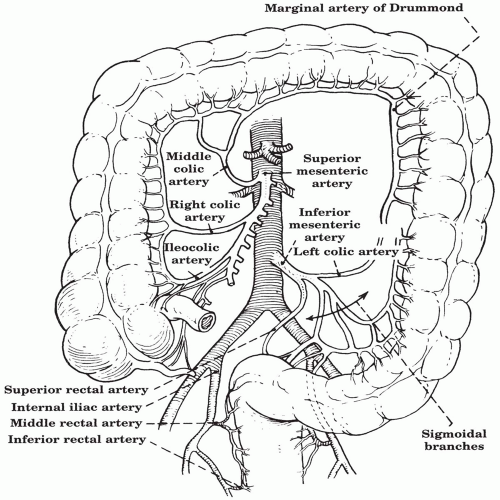

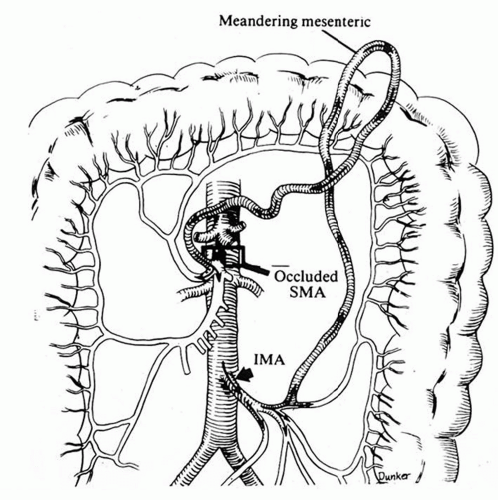

Certain anatomic features of the mesenteric circulation determine symptoms and influence management of intestinal ischemia (Fig. 17.1). The celiac axis supplies the foregut, the superior mesenteric artery (SMA) the midgut, and the inferior mesenteric artery (IMA) the hindgut. Although the three major mesenteric arteries supply specific territories, they normally intercommunicate by excellent collateral channels. These collaterals enlarge when a proximal mesenteric artery is stenotic or occluded. The primary collateral pathways between the celiac and superior mesenteric arteries are via the gastroduodenal artery to the pancreaticoduodenal arcade that connects with the superior mesenteric artery. The inferior mesenteric artery has two main sources of collateral flow when it is obstructed (Fig. 17.2). The middle colic branch of the superior mesenteric artery connects around the transverse colon to the marginal artery of Drummond, a continuation of the left colic branch of the inferior mesenteric artery. In some instances a more direct connection in the left mesocolon develops more centrally from the marginal artery. This is known as the Arc of Riolan, or meandering mesenteric artery (Fig. 17.3). The inferior mesenteric artery also receives collateral flow via the middle hemorrhoidal artery, a branch of the internal iliac artery. These abundant collateral channels for mesenteric circulation explain the clinical observation that intestinal angina usually does not occur until at least two of the three main mesenteric arteries have severe occlusive disease.

CLINICAL PRESENTATION

Intestinal ischemia is classified as either chronic or acute. However, the presentations may overlap, since chronic intestinal stenosis can progress to acute thrombosis and intestinal infarction.

I.

Chronic mesenteric ischemia (CMI) often eludes early diagnosis because the chronic abdominal pain is attributed to some other GI disorder. Frequently, the patient has undergone a negative diagnostic evaluation of the gallbladder, liver, and entire GI tract with CT, contrast swallows and enemas, and upper and lower endoscopies. Because of progressive weight loss, some patients are mistakenly thought to have cancer. Certain clinical features, however, should raise suspicion of chronic intestinal ischemia. Characteristic symptoms are abdominal pain and significant weight loss.

A.

Classically, the chronic abdominal pain is intermittent and postprandial. It usually is localized to the epigastrium and has a dull ache, crampy, or colicky quality that begins 30 to 60 minutes after eating and may persist for a few hours. Patients may have associated abdominal bloating or diarrhea.

B.

Involuntary weight loss eventually occurs because the patient associates eating with pain. Consequently, a “food fear” develops. While actually avoiding food altogether is rare, oral intake often is modified until liquids become the primary nutrient.

C.

Physical findings of chronic intestinal ischemia are limited primarily to weight loss and an abdominal bruit, which is present in over half of individuals. Since the weight loss usually is insidious over several months and many patients with atherosclerosis have abdominal bruits, the significance of these nonspecific findings often is overlooked when the patient initially presents.

D.

Chronic intestinal ischemia should be suspected in any adult who has chronic abdominal pain, progressive weight loss, other signs of generalized cardiovascular disease, and a negative workup for more common GI disorders. Some 70% of patients with CMI have been diagnosed with peripheral vascular disease in other territories. They are usually younger than standard aneurysmal or occlusive disease patients (midsixties), are smokers, and over half are women. These features collectively should lead to the following simple questions of patients suspected of having peripheral vascular disease: (1) Do you have abdominal pain after meals? (2) Have you experienced significant weight loss in the past one or two months?

II.

Acute mesenteric ischemia (AMI) has three main etiologies: thrombosis of an arterial stenosis, embolism, and nonocclusive small-vessel insufficiency. Very rarely, venous mesenteric thrombosis may occur. Although the initial symptom for all these etiologies is abdominal pain, the clinical setting often suggests the most likely underlying cause. The frequency of each etiology may vary among medical centers, but generally acute intestinal ischemia is caused by thrombosis in 40% of cases, embolism in another 40%, and intestinal hypoperfusion in 20% of cases.

A.

Severe generalized abdominal pain that is disproportionate to the physical findings remains the classic presentation of acute intestinal ischemia. Nausea, vomiting, or diarrhea may follow shortly after the onset of symptoms and are very common. Although the abdomen may have diffuse tenderness, bowel sounds may be heard and peritoneal signs usually are absent. The only early laboratory abnormality may be a mildly elevated white blood cell count. With these findings the clinician must entertain the possibility of AMI and undertake steps to alleviate it. Aggressive radiologic and surgical intervention at this point can salvage the ischemic intestine in about 50% of such patients.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree