Mesenchymal Tumors of the Mediastinum

Thomas W. Shields

Philip G. Robinson

Primary benign and malignant mediastinal mesenchymal tumors are infrequent. Wychulis,235 Luosto,126 and Davis44 and their colleagues as well as Teixeira and Bibas210 have reported an incidence of generally <6% of all mediastinal masses. King and associates110 reported a somewhat higher incidence in children of 10.7%. Of these mesenchymal tumors, Wychulis and colleagues235 from the Mayo Clinic reported about 55% to be malignant; from the same institution, King and associates110 reported an 85% incidence of malignancy in soft tissue mediastinal tumors in children. Jaggers and Balsara99 point out that, also in children, vascular lesions such as hemangiomas, hemangiosarcomas and cystic hygromas (lymphangiomas) account for 3% to 6% of mediastinal masses. In their review, Macchiarini and Ostertag128 indicate that mesenchymal tumors account for less than 10% of adult primary mediastinal tumors. Swanson205 has reviewed the pathology of mesenchymal mediastinal tumors. Lee and colleagues122 reviewed the computed tomography (CT) findings of mesenchymal thoracic tumors. Kransdorf and Murphey119 recently authored a book that nicely defines the imaging studies of soft tissue tumors. A comprehensive textbook of soft tissue pathology is Weiss and Goldblum’s fifth edition of Enzinger & Weiss’s Soft Tissue Tumors.225

Burt and colleagues23 reviewed the records at Memorial Sloan-Kettering Cancer Center from January 1, 1990, to December 31, 1991. They found 47 patients with primary mediastinal sarcomas. The patients ranged in age from 2.5 to 69.0 years, with a median age of 39 years. The ratio of men to women was 1:6. Forty-two (89%) of the patients were symptomatic; their presenting complaints included chest or shoulder pain (38%), dyspnea (23%), cough (9%), paresthesias (9%), hemoptysis (6%), and various other complaints. The medical history of these patients was significant for von Recklinghausen’s disease in three, irradiation to the chest for lymphoma in five, and radiation therapy for retinoblastoma in one. The mediastinal distribution of the tumors was 49% in the posterior compartment, 41% in the anterior compartment, and 10% in the visceral compartment. The most common tumors were malignant peripheral nerve tumor (26%), spindle-cell sarcoma (15%), leiomyosarcoma (9%), and liposarcoma (9%).

Many classifications for mediastinal mesenchymal neoplasms have been suggested, but none are completely satisfactory because they frequently include generalized mesenchymal lesions within the thorax involving the lungs and mediastinum as well as the aorta and pulmonary vessels. Also, we believe that malignant neurogenic sarcomas should be excluded from the global category of mesenchymal tumors. We have adapted our classification from the one given by Fletcher, Unni, and Mertens68 in the World Health Organization (WHO) book on soft tissue tumors. This is a widely accepted classification among pathologists. In it, the tumors are categorized in two ways. The first is to their cell of origin, if it is known, and the second is to the tumor’s biological potential. The biological potential category is divided into three groups: (a) benign, (b) intermediate (which is subdivided into “rarely metastasizing” and “locally aggressive”), and (c) malignant.

Since the previous edition of this book was published, Fletcher69 has described several important conceptual changes in our thinking about the pathology of soft tissue tumors. Some of these concepts are as follows: (a) malignant fibrous histiocytoma is not a definable entity but instead is a wastebasket of undifferentiated pleomorphic sarcomas accounting for no more than 5% of adult soft tissue sarcomas; (b) hemangiopericytomas show no evidence of pericytic differentiation—rather, they are fibroblastic in nature and form a morphologic continuum with solitary fibrous tumor; and (c) in many of the mesenchymal tumors, we do not know either the cells of origin or the line of differentiation of the mesenchymal tumors, which puts some tumors in a category of uncertain differentiation. The malignant fibrous histiocytomas and hemangiopericytomas are discussed in greater detail under their own headings.

Our working classification of mediastinal mesenchymal neoplasms is presented in Table 199-1; it follows the WHO classification of soft tissue tumors of Fletcher, Unni, and Mertens.68 Some of the lesions are not included in the WHO classification.

Adipocytic Tumors

Lipoma

Incidence

Benjamin and associates16 reported an incidence of 1% of lipomas in a collected series of 1,064 mediastinal neoplasms. Strug and colleagues197 reported an incidence of 1.8% in 106 patients,

and Teixeira and Bibas210 recorded an incidence of 1.7% in 179 patients in their series, excluding the 14 substernal thyroid goiters and 6 leiomyomas of the esophagus that they listed in their total of 199 solid mediastinal masses. Moigneteau and associates143 noted that mediastinal lipomas of nonthymic origin are more common than are thymolipomas.

and Teixeira and Bibas210 recorded an incidence of 1.7% in 179 patients in their series, excluding the 14 substernal thyroid goiters and 6 leiomyomas of the esophagus that they listed in their total of 199 solid mediastinal masses. Moigneteau and associates143 noted that mediastinal lipomas of nonthymic origin are more common than are thymolipomas.

Table 199-1 Primary Mesenchymal Tumors of the Mediastinum Classified According to the 2002 Classification of the World Health Organization | ||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Clinical Features

Lipomas occur most commonly in adults. Kleinhaus and Ducharmre113 noted that of the 120 cases in the literature at the time of their publication, fewer than 10 were recorded in children younger than the age of 10 years. According to Staub and colleagues,190 men appear to be affected twice as often as women. More than half of the mediastinal lipomas produce few if any symptoms. When the lesion is large, respiratory symptoms, such as dyspnea, may occur because of compression of adjacent lung. Most such lesions are located in the anterior compartment, but they may develop in either the visceral compartment or one of the paravertebral sulci. The lesion is most often solitary, but multiple lesions are occasionally seen.

Keeley and Vana104 classified the mediastinal lipomas as totally intrathoracic (the more common type) and as hourglass (i.e., the cervicomediastinal or transmural type). In the transmural variety, the fatty tumor may extend through an intercostal space or spaces into the chest wall or even through an intervertebral foramen into the spinal canal, as reported by Quinn and associates.162 Negri and colleagues149 reported a similar occurrence in a patient with an angiolipoma in the paravertebral region. A one-stage neurosurgical and video-assisted thoracic surgery (VATS) removal was carried out successfully.

Radiographic and Computed Tomographic Features

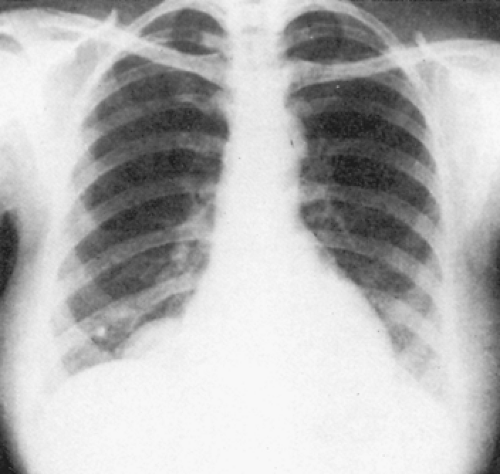

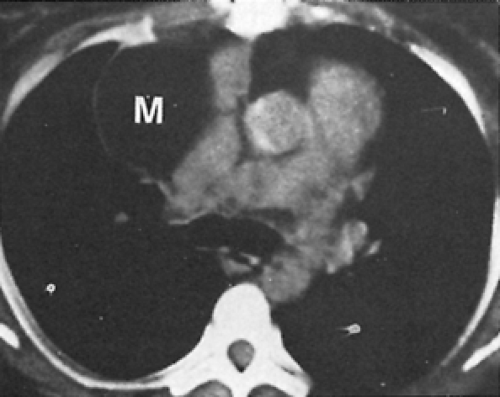

Radiographic features are not diagnostic, but occasionally the lesion may appear less dense, especially at its periphery, than other solid tumors (Fig. 199-1). Penetrated Bucky radiographs are best suited to demonstrate the lesser density of these tumors as compared with the surrounding structures. Examination of the patient in different positions may reveal different contours of the mass because of the effect of gravity on the soft, pliable fatty tissue. With the patient in an upright position, an hourglass or teardrop configuration is noted occasionally. Pure mediastinal lipomas can be distinguished from thymolipomas because they usually lack the characteristic bilobate shape of the latter lesions. A lipoma has a lower characteristic coefficient of density on computed tomography (CT) scans, which allows its identification (Fig. 199-2). The CT density of lipoma is in the range of 70 to 130 Hounsfield units.

Pathology

A lipoma is a well-circumscribed, encapsulated, soft yellow mass that may readily be excised. Histologically, the tumor is composed of lobules of mature fat.

Treatment

Surgical excision through the appropriate thoracic incision or a VATS approach is curative. With a paravertebral lipoma, extension into the spinal canal must be looked for by preoperative CT or magnetic resonance imaging (MRI). If extension into the spinal canal is identified, single-stage excision, as described in Chapter 197, is indicated.

Variants of Mediastinal Lipomas

A number of lipomas contain significant amounts of additional mesenchymal tissues; thus a number of lipomatous lesions have been recorded by different terms to denote the presence of the other cell types. Kline and associates115 reported the occurrence of an angiolipoma in the visceral mediastinal compartment, and, as noted, Negri and colleagues149 recorded one occurring in the paravertebral space. Lim125 reported a patient who had a chondrolipoma located in the superior region of a paravertebral sulcus. Excision is the treatment of choice for all the aforementioned tumors.

Kim and colleagues108 reported a primary myelolipoma of the mediastinum. According to the review of Sabate and Shahian,173 Foster71 reported an earlier case. Suzuki204 and Gao77 and their associates have presented additional cases. The last authors noted that only 12 cases of mediastinal myelolipoma had been reported in the Japanese literature. These tumors in the mediastinum are most commonly located in the “posterior” compartment. Such myelolipomas are more common than the primary myelolipomas located in the lung. The radiographic, CT, and MRI features, as noted by Kawanami and associates,103 are the same as those described for the pulmonary myelolipomas in Chapter 124. The essential diagnostic feature of a myelolipoma is the presence of bone marrow with ectopic megakaryocytes within the lipomatous tumor. The diagnosis is most often established by examining tissue obtained by fine-needle aspiration (FNA) of the mass. The treatment is surgical excision if the tumor is large or symptomatic.

Lipomatosis

Lipomatosis is a diffuse overgrowth of mature adipose tissue that can occur in different parts of the body. Diffuse lipomatosis is usually localized to an extremity or to the trunk. Pelvic lipomatosis is localized to the pericolonic and perivesicular areas. Other types of lipomatosis are symmetric lipomatosis, adiposis dolorosa (Dercum’s disease), and corticosteroid lipomatosis. Pathologically, the adipose tissue in lipomatosis is composed of mature fat cells with no cytologic evidence of malignancy.

Symmetric lipomatosis may be a cause of mediastinal widening. Homer and colleagues89 reported the value of CT examination to identify the condition. In about half of the patients with this infrequent condition, lipomatosis results from exogenous obesity, corticosteroid ingestion as noted by Shukla and colleagues,185 or Cushing’s syndrome. Once the lesion is identified by CT scanning, no further intervention or treatment is necessary.

Lipoblastoma/Lipoblastomatosis

A lipoblastoma/lipoblastomatosis is a tumor resembling fetal adipose tissue. It occurs either as a localized or circumscribed tumor that is called lipoblastoma or a diffuse or infiltrating tumor that is called lipoblastomatosis. Both lesions occur in children who are usually <3 years of age; Vellios and associates217 were the first to describe the tumor. It most often occurs in one of the extremities but can also be seen in the neck, chest wall, and paravertebral soft tissues. The tumor is composed of an admixture of mature and immature adipocytes arranged in a lobular pattern. A case of lipoblastoma in the mediastinum was reported by Tabrisky and colleagues206; the tumor arose posteriorly at the level of the azygos, extended to the apex, and spread to fill the right hemithorax. Surgical excision of a circumscribed lesion is curative, but the diffuse form may recur.

Extrarenal Angiomyolipoma

Fukuzawa and colleagues75 and later Watts and Watts223 reported a case of an angiomyolipoma in the anterior mediastinum of a 57-year-old woman. Only eight cases of mediastinal angiomyolipomas have been reported in the literature. They are benign mesenchymal tumors composed of blood vessels, adipose tissue, and smooth muscle. Immunohistochemically, these tumors stain with desmin and HMB-45. These lesions are usually found in the kidneys and are associated with tuberous sclerosis and lymphangioleiomyomatosis. In the kidney, these tumors are usually resected because they may rupture and bleed. Surgery is the treatment of choice.

Hibernoma

Hibernoma is an uncommon benign tumor that arises from remnants of brown fat and may be admixed with a variable proportion of white adipose tissue. Less than 100 cases have been described; of these, seven have occurred in the thorax. These intrathoracic hibernomas were reviewed by Ahn and Harvey.2 In five patients, the hibernoma was located in the subpleural space, one was intrapericardial, and one was located in the anterior mediastinum. A cervicomediastinal hibernoma was reported by Santambrogio and coworkers.175 This lesion, although described as extending into the anterior mediastinum, actually extended down into the pretracheal portion of the visceral compartment, as do most substernal goiters. The mass was large; it distorted the trachea and splayed the vessels laterally. CT revealed a mixed density consisting mainly of fat. Surgical resection is curative.

Liposarcoma

Introduction

Liposarcomas are malignant tumors of adipocytes. They are divided into locally aggressive tumors and malignant tumors. The locally aggressive tumors are the atypical lipomatous tumor also known as the well-differentiated liposarcoma. These tumors do not seem to have the ability to metastasize, but they can recur if not completely excised. In superficial locations, they are called atypical lipomatous tumors (beneath the skin); in deep locations, they are called well-differentiated liposarcomas. The liposarcomas with the ability to metastasize include the (a) myxoid, (b) dedifferentiated, and (c) pleomorphic types. The round cell type of liposarcoma has been incorporated into the myxoid type.

Incidence

Standerfer and colleagues189 added two cases to the 51 cases reviewed by Schweitzer and Aguam in their report.179 Teixeira and Bibas210 added an additional case, and numerous single case reports have been added to the literature since that report. The greatest number of additional cases were reported in a review of the Japanese literature by Minamoto and colleagues in 1996.142 Men and women are affected equally. Two-thirds of the patients are >40 years of age; the average age is approximately 45 years. Less than 5% of patients are <16 years of age, and only two patients, one reported by Kauffman and Stout102 and one by Wilson and Bartly,231 have been <3 years of age. Castleberry and associates27 report that in children, only 11% of all liposarcomas arise in the mediastinum.

Clinical Features

According to Mendez and associates,136 liposarcomas are most common in the posterior mediastinum (i.e., the paravertebral sulcus and posterior portion of the visceral compartment), but they may occur in any location within the mediastinum. Schweitzer and Aguam179 reported that 85% of patients with a liposarcoma are symptomatic, whereas only 15% have an asymptomatic lesion discovered only on routine chest radiography. Most patients present with respiratory symptoms of dyspnea, tachypnea, wheezing, and cough. Half the patients present with pain or pressure within the thorax or shoulder region. Significant weight loss is seen in 25%, and the signs and symptoms of superior vena cava obstruction are seen in 15%.

Radiographic and Computed Tomographic Features

Liposarcomas are large, lobulated masses with ill-defined borders on radiography of the chest. Adjacent structures may be compressed and infiltrated. Mendez and associates136 reported that liposarcomas have a density intermediate between that of water and fat. The density of these lesions is greater than that of a benign lipoma. The more poorly differentiated tumor with a greater number of abnormal cells may have a Hounsfield unit number as high as 15 to 20. The aforementioned authors suggest that this finding is useful in distinguishing lipomas from

liposarcomas. However, the clinical features in most patients readily permit this differentiation.

liposarcomas. However, the clinical features in most patients readily permit this differentiation.

Pathology

In the older classification of liposarcomas the round cell type was viewed as a separate tumor. Antonescu and Ladanyi5 and most other authorities now agree that the round cell liposarcoma is best classified with the myxoid liposarcomas and viewed as a higher grade of this tumor. Liposarcomas are now divided into four types: (a) well-differentiated or atypical lipomatous tumor; (b) myxoid, including the round cell; (c) dedifferentiated; and (d) pleomorphic. Myxoid liposarcomas account for 40% to 50% of all liposarcomas. The pathology report should estimate the percent of the myxoid and round cell components as well as the percentage of tumor necrosis. Evans59 described an atypical lipomatous tumor of the mediastinum with bundles of smooth muscle. The patient developed several recurrences. Atypical lipomas are now viewed as being almost synonymous with well-differentiated liposarcomas. They are locally aggressive, but do not seem to have the ability to metastasize. Consequently, the pathologist will generally diagnose the superficial ones as atypical lipomas and deep ones as well-differentiated liposarcomas even though they both have similar histology. The deep ones tend to recur because they cannot be completely excised. In contrast, the superficial ones can generally be completely excised. Liposarcomas are usually large. This observation may be due to a lack of symptoms and the fact that mediastinal ones are of low grade. In the cases of Klimstra and associates,114 they ranged from 6 to 40 cm, with an average size of 15.7 cm and a mean weight of 1,500 g. They appear circumscribed but are not encapsulated. They may arise in any of the mediastinal divisions and extend into either or both hemithoraces or even into the neck. The well-differentiated type made up 60% of the tumors, with the myxoid type being 28%; the remaining tumors, which exhibit mixed features, made up 12%. On cut section, the surface of the tumor may have a gelatinous appearance and it may be pale yellow, bright orange, white, or gray–white. In other areas, the tumor may show focal necrosis, hemorrhage, or cyst formation.

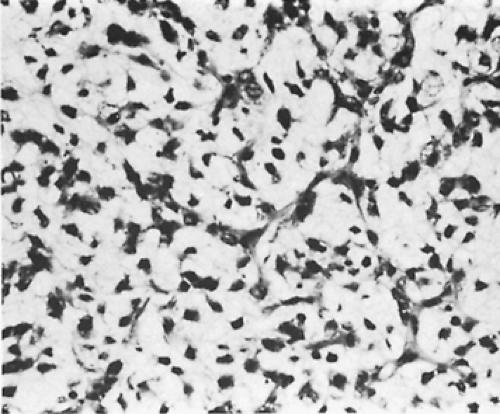

In 44 cases of primary mediastinal liposarcomas in the Japanese literature reviewed by Minamoto and colleagues,142 the myxoid type represented 34.4% of the tumors and the well-differentiated type made up 28.1%; 10% were either of the pleomorphic or round cell types, and the remaining 27% could not be classified specifically. On microscopic examination, the myxoid subtype is composed of lipoblasts set in a myxoid matrix with a background network of delicate capillaries. All of the tumors contain varying numbers of malignant lipoblasts with other cells having spindle-shaped nuclei. A round cell component may be present that shows cells with enlarged round to oval hyperchromatic nuclei and foamy cytoplasm (Fig. 199-3). A characteristic chromosomal translocation in these tumors—t(12;16) (q13;p11)—has been described by Knight and associates.116 According to Kindblom and colleagues,109 about half of the patients with myxoid liposarcomas develop local recurrences, whereas only a small percentage of patients develop metastases. Well-differentiated liposarcomas are less aggressive neoplasms than myxoid ones. In contrast, the dedifferentiated and pleomorphic liposarcomas are aggressive neoplasms. They can produce widespread metastases to the lungs, bones, and other organs.

Treatment

When possible, complete surgical excision is the preferred therapeutic choice. A standard open operation is indicated if the mass is thought to be malignant. Marulli and associates132 reported the recurrence of a myxoid liposarcoma in a 29-year-old woman after 24 months. The recurrent tumor was resected and the patient was alive and well 24 months following the second surgery. Aubert and colleagues7 reported intrapleural metastases and implantation of a low-grade myxoid liposarcoma after its initial removal by a VATS technique. Unfortunately, contamination of these sites occurred during the removal of the tumor. These authors point out that VATS probably is not indicated for the removal of possibly malignant tumors of the mediastinum. Subtotal resection is often used but is only of short-term palliative benefit, with early recurrence despite postoperative adjuvant therapy. Radiation therapy is of little avail owing to the dosage that can be used in most cases with the disease located in the chest. However, Grewal and associates83 reported a 75-year-old patient who had survived longer than 5 years after a partial excision and adjuvant radiation of a nonencapsulated liposarcoma of the anterior mediastinum. Castleberry and colleagues27 have suggested the judicious use of radiation therapy and chemotherapy (i.e., vincristine, dactinomycin, and cyclophosphamide) to reduce the size of an initially inoperable tumor. They have reported some success with this approach in a child.

Prognosis

The pseudoencapsulated lesions that can be completely removed have a better prognosis than the nonencapsulated, infiltrative tumors. Standerfer and colleagues189 reported a few cases of patients surviving 3 to 17 years after resection of

pseudoencapsulated lesions. The patients with nonencapsulated lesions or one of the less well differentiated tumor types have a poor prognosis and as a rule die within 2 years. Follow-up of the cases presented by Klimstra and associates114 was available in 23 of 28 patients for between 1 month and 6 years. They reported that 7 (31.8%) of their patients died of their tumors after a mean interval of 2.6 years, while 11 (47.8%) were free of disease after a mean interval of 1.6 years. The patients with myxoid liposarcomas died after a shorter interval. These investigators did not have many of the higher-grade liposarcomas in their series. Patients presenting with a superior vena cava syndrome have an extremely poor prognosis, as noted by McLean and coworkers.135 Two such patients, one reported by Kozonis and associates118 and one reported by Schweitzer and Aguam,179 died within a short time of presentation.

pseudoencapsulated lesions. The patients with nonencapsulated lesions or one of the less well differentiated tumor types have a poor prognosis and as a rule die within 2 years. Follow-up of the cases presented by Klimstra and associates114 was available in 23 of 28 patients for between 1 month and 6 years. They reported that 7 (31.8%) of their patients died of their tumors after a mean interval of 2.6 years, while 11 (47.8%) were free of disease after a mean interval of 1.6 years. The patients with myxoid liposarcomas died after a shorter interval. These investigators did not have many of the higher-grade liposarcomas in their series. Patients presenting with a superior vena cava syndrome have an extremely poor prognosis, as noted by McLean and coworkers.135 Two such patients, one reported by Kozonis and associates118 and one reported by Schweitzer and Aguam,179 died within a short time of presentation.

Vascular Tumors

Vascular tumors of the mediastinum are encountered infrequently. In the reviews of Wychulus235 and Benjamin16 and their associates, these tumors accounted for less than 0.5% of all mediastinal tumors. They may occur at any age and show no predilection for either gender. The anterior compartment is most often the initial site of origin, but neither the middle compartment nor the paravertebral sulci are spared the presence of these lesions. Balbaa and Chesterman10 reviewed more than 60 cases. With the data then available, benign lesions were more than twice as common as malignant ones. This figure for benign lesions is too low; the benign tumors probably account for almost 90% of the vascular mediastinal lesions.

According to Cohen and colleagues,35 about half of the benign lesions are asymptomatic. In contrast, almost all of the malignant lesions reported in the literature are symptomatic. The classification of vascular tumors has evolved since the earlier editions of this book. The benign and malignant hemangiopericytomas are no longer considered to be of pericytic origin. Guillou and colleagues84 describe how this entity is being merged into the tumors known as solitary fibrous tumor, giant-cell angiofibroma, and lipomatous hemangiopericytoma, with all of these being placed in the fibroblastic/myofibroblastic group of tumors. Finally, the term hemangioendothelioma remains confusing because in the past it was used for benign, intermediate, and malignant lesions. Currently, the term refers to vascular tumors of intermediate malignancy (locally aggressive or rarely metastasizing). The one exception is the epithelioid hemangioendothelioma, which is considered to be malignant.

Hemangiomas

Incidence

Cohen and associates35 reported 88 mediastinal hemangiomas that had been described in the literature and added 15 patients of their own. Rodriguez Paniagua and associates,169 in a discussion of the aforementioned report, added four more cases. Hemangiomas constitute about 90% of all vascular mediastinal tumors. Moran and Suster146 described 18 patients with mediastinal hemangiomas. Yamazaki and associates,238 in a 50-year review of mediastinal tumors in Japan, found 5 out of 1,546 (0.32%) to be hemangiomas.

Clinical Features

One-third to almost half of patients are asymptomatic. The remaining patients present with symptoms or signs that are the result of infiltration of adjacent structures or fullness in the neck, which is often present with anteriorly situated tumors. Chest pain, dyspnea, cough, and hemoptysis are common complaints. Superior vena cava obstruction, Horner’s syndrome, and other neurologic findings, as well as spinal cord compression, have also been described in these patients. In the hemangiomas described by Moran and Suster,146 the most common complaints were chest pain, cough, and dyspnea. The patients ranged in age from newborn to 74 years with a mean age of about 43 years and a male–female ratio of 1:1. Four of the tumors were located in the posterior compartment and fourteen were located in the anterior one. Kissel and associates112 noted the occasional association of mediastinal hemangiomas and Osler-Weber-Rendu disease, and Kings111 noted its association with multiple hemangiomas elsewhere in the body.

Radiologic Features

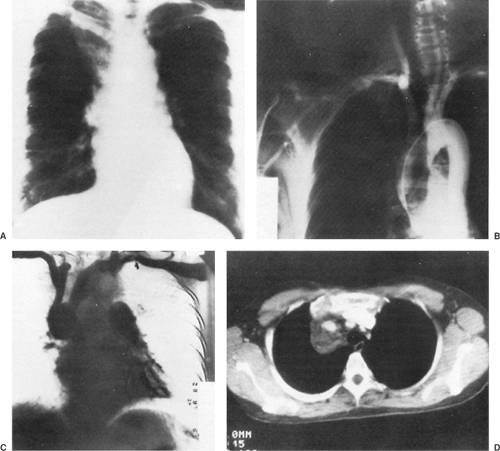

Radiography of the chest reveals the lesion, but as a rule it is of no help in suggesting the correct diagnosis (Fig. 199-4A). Phleboliths may be present in as many as 10% of the patients, but in the 15 patients described by Cohen and colleagues,35 none were found. Angiography has not been helpful in the diagnosis of these lesions because they are not opacified by the contrast material (Fig. 199-4B). In Cohen and associates’ series,35 a venogram was successful in visualizing an anterior mediastinal hemangioma in one patient (Fig. 199-4C). CT scanning is excellent for delineating the lesion and its relationship to adjacent structures (Fig. 199-4D) and may suggest the presence of infiltration. The density of the lesion is the same as that of the surrounding vascular structures. Cohen and associates36 reported that CT scans of hemangiomas are characteristic. The masses have an attenuation of approximately 30 Hounsfield units. Phleboliths can usually be demonstrated on CT but not on chest radiography. Contrast enhancement is useful in making the diagnosis if the bolus is followed by sequential scans. The contrast material gradually collects in the tumor, with the enhancement appearing at the periphery and gradually filling up the center. In addition, CT may suggest the best operative approach to the mediastinal lesion. McAdams and colleagues134 reviewed the radiographic and CT findings of 14 patients with mediastinal hemangiomas. They concluded that hemangiomas should be considered in the differential diagnosis of well-marginated mediastinal masses that have heterogenous attenuation on CT scans, show central enhancement after administration of contrast material, or contain punctate calcification.

Schurawitzki and colleagues178 described the MRI findings of two mediastinal hemangiomas. In the first patient, the T1-weighted images showed a lesion with irregular contours that was homogenous and hypointense when compared with fat. The T2-weighted images showed an inhomogeneous increase in signal intensity. After gadolinium diethylenetriamine penta-acetic acid was injected, moderate inhomogeneous enhancement was seen. The second patient showed multiple circumscribed, hyperintense areas on T1- and T2-weighted images that were caused by intratumoral hemorrhage (hemo-siderin).

Pathology

On gross examination, hemangiomas are usually well circumscribed and may appear as a soft, compressible, purplish mass. They may appear as an amorphous soft mass that insinuates itself among the various adjacent vascular or neurogenic structures. This is particularly true in the visceral compartment, and the tumor may be adherent to or even appear to be infiltrating the superior vena cava or other structures. In a paravertebral sulcus, it may involve the sympathetic chain or rarely extend into the spinal canal through an enlarged intervertebral foramen.

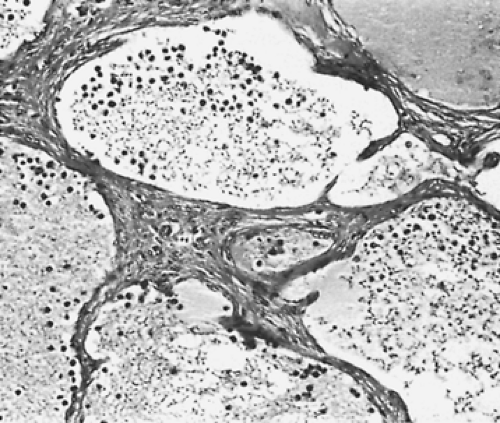

On microscopic examination, the hemangiomas of Moran and Suster146 could be divided into two groups: (a) capillary (7 patients) and (b) cavernous (11 patients). The capillary hemangiomas grow in a lobular pattern separated by thin fibrous septa. The lobules are composed of a solid proliferation of endothelial cells with compressed vascular lumens. In contrast, the cavernous hemangiomas are composed of large irregular dilated blood vessels lined by flattened endothelial cells and partially filled with blood. The walls may show some fibrosis and focal chronic inflammation (Fig. 199-5). Because the blood flow is slow through these vessels, they frequently thrombose and develop dystrophic calcifications (phleboliths). Pusztaszeri and colleagues161 would expect these tumors to immunostain with the common markers for endothelial cells, such as CD31, CD34, and von Willebrand factor.

Treatment

Surgical excision is the treatment of choice. Radiation therapy is of no benefit in the management of these lesions. The tumor may be approached either through a standard posterolateral thoracotomy, a median sternotomy incision, or even a transsternal (clamshell) incision. All of the patients reported by Cohen and associates35 had the surgical procedure carried out through a standard posterolateral approach. However, Rodriguez Paniagua and colleagues169 recommend the use of a median sternotomy. The choice of incision should be determined by the tumor’s location and extent as defined by CT examination.

When possible, total excision of the hemangioma should be carried out. At times, because of infiltration of adjacent vital or bony structures, only partial excision or even only a biopsy of the lesion can be accomplished. Cohen and associates35 were able to excise 6 of 12 tumors completely. A subtotal resection was carried out in five patients, and only biopsy could be accomplished in one. Despite the subtotal resection or biopsy only, major hemorrhage was not a problem in any of these patients. Rodriguez Paniagua and colleagues,169 however, reported fatal postoperative exsanguination in a patient after partial excision of a mediastinal hemangioma. As a result, these authors suggest that only total resection of the vascular tumor should be done. In two of their patients, resection of the superior vena cava with the tumor and the replacement of this vein by a prosthetic graft led to excellent results. Cohen and colleagues,37 from their previously reported experience, continue to support the concept of partial resection when total excision appears impossible or excessively hazardous.

Results

The prognosis after total or partial excision is excellent. Cohen and colleagues35 reported only one suspected radiologic recurrence in the patients undergoing total excision and one symptomatic recurrence that required reoperation after partial excision. The remaining patients, including the one patient with a biopsy only, did not have progression of their disease on long-term follow-up. Likewise, no evidence of malignant transformation has been observed. The 18 cases of Moran and Suster146 were followed for between 1 month and 4 years after surgery and all were alive and well with no evidence of recurrence.

Lymphangioma

Incidence

Less than 1% of lymphangiomas are confined to the mediastinum. In children, most of those occurring in the mediastinum arise in the neck and extend into the mediastinum (cervicomediastinal cystic hygromas); these are discussed in detail in Chapter 175. In adults, however, they tend to lack the cervical component. Rarely, the lesion is associated with a generalized process such as lymphangiomatosis, Gorham’s disease, lymphangiomyomatosis, Klippel–Trenaunay syndrome, or lymphatic varices.

Of the isolated mediastinal lymphangiomas, Ricci and associates165 stated that 48% are identified in the anterior compartment, 34% in the visceral compartment, and 9% in the paravertebral sulci. These figures may be unreliable, however, because of differences in terminology for the mediastinal divisions used in the literature. Because the lesion is very uncommon, most reports of mediastinal lymphangiomas are individual case reports. The reports of Soler,182 Daya,45 and Oshikiri152 and their colleagues fall into this category, although the report of Oshikiri contains five cases. The most comprehensive papers are two from the Mayo Clinic. The first is by Brown and colleagues,21 who described 14 mediastinal lymphangiomas, and the second is by Park and associates,155 who described another 12 cases and discussed both cohorts of patients. In the latter paper, one of the original 14 cases was dropped because the patient had a revised diagnosis of Gorham’s angiomatosis. In the first paper, three tumors (43%) were located in the anterior compartment, two (28%) in the visceral compartment, and two (28%) in a paravertebral sulcus. Six patients were adults and one was an adolescent. Of the remaining lesions, two were located in the paravertebral sulcus with retroperitoneal extension and four either arose or extended into the neck. In the additional 12 cases reported by Park and associates,155 9 (72%) were mediastinal and 3 (24%) were cervicomediastinal, with 10 having a superior mediastinal component. These patients ranged in age from 5 days to 81 years with a mean age of 36.5 years, and the male–female ratio was 1:3.

Clinical Features

Patients with isolated tumors are generally asymptomatic. In the cases of Park and colleagues,155 three were asymptomatic. In the other nine, the symptoms included dyspnea, hemoptysis, chest pain, and fever; four patients presented with more than one symptom. The most commonly associated medical condition was valvular heart disease in 4 of 12 patients (33%). Symptoms of compression of adjacent structures, dyspnea, or a symptomatic chylothorax, such as that described by Johnson and coworkers,99 may be present infrequently.

Radiographic and Computed Tomography Features

On standard films, the lymphangioma appears as a smooth, rounded, or lobulated mass. It is of uniform density. Depending on its location, it may deviate the trachea or compress or distort other adjacent structures, such as the esophagus. With a lesion located in a paravertebral sulcus, erosion of one or more vertebral bodies may be noted. A lymphangiogram may occasionally fill the lesion with contrast material or demonstrate the egress of the material into the pleural space when a chylothorax is present. The CT features of mediastinal lymphangioma have been described by Pilla and associates.159 These consist of (a) a well-circumscribed lesion without invasive characteristics, (b) normal structures that have been enveloped or displaced, (c) absence of calcifications, and (d) varied attenuation values within the lesion. Shaffer and associates180 described both the CT and MRI findings of mediastinal lymphangiomas. Their most common CT finding was a well-circumscribed, uniformly cystic mass in the anterior or superior mediastinum. MRI findings parallel those of the CT scan with cystic components. The T1-weighted images showed a signal greater than muscle, and one case showed a T2-weighted image with a decreased signal. The advantages of MRI are (a) demonstration of cystic components, (b) lack of demonstration of invasion, and (c) improved surgical planning with coronal and sagittal images. Shaffer and associates180 concluded that the CT and MRI views of lymphangiomas were variable but that the diagnosis could not be suggested on the basis of the radiologic studies alone.

Charruau29 and Oshikiri152 and their coworkers also described the CT and MRI findings of mediastinal lymphangiomas. On CT examination, the margins of the lymphangiomas are smooth, with the majority of cases showing no enhancement with contrast. In the series of Charruau and associates,29 three patients had MRI scans. On T1-weighted images, one case showed low signal intensity and two showed intermediate intensity. On T2-weighted images, the signal was high in all three cases but heterogeneous in two. In the gadolinium-enhanced T1-weighted images, two of the cases showed multiloculated masses with enhancing septa. Oshikiri and colleagues152 did an MRI examination of a cavernous lymphangioma and it showed multilocular septa. Both groups concluded that CT and MRI studies are useful in diagnosing mediastinal lymphangiomas.

Pathology

Lymphangiomas are benign tumors of the lymphatics composed of large dilated cystic lymph channels. These tumors have been called cavernous lymphangioma, cystic hygroma, lymphatic cyst, cystic lymphangioma, multiloculated hygroma, and chylous cyst. The lymphangioma may either appear encapsulated or have ill-defined margins with envelopment or insinuation of the tumor between adjacent structures. It may be adherent to adjacent vessels, nerves, or the pericardium. Erosion of adjacent bony structures, rather than invasion, is seen with lesions that abut the rib cage or the vertebral column. The lesion is soft, spongy, and grayish. The cystic structures of the mass may be macroscopic or microscopic. The lymphangioma contains chyle, which grossly differentiates the lesion from a hemangioma, which contains blood. Morphologically, the lesion may be classified according to the size of the lymphatic spaces into cystic hygromas, composed of large cystic spaces, or cavernous lymphangiomas, composed of a sponge-like mass of smaller spaces. Microscopically, attenuated endothelial cells similar to those of normal lymphatics line the spaces in both these lesions. Fukunaga74 pointed out that immunochemistry with D2-40 is very useful in identifying lymphangiomas, because normal lymphatic endothelium stains for this glycoprotein. However, the histologic evaluation is important, because D2-40 will also stain Kaposi’s sarcoma, angiosarcoma, and the papillary intralymphatic angioendothelioma (Dabska tumor). Unilocular cysts also have been described, but in the report of 18 such cases by Childress and associates,32 many of these lesions most likely represented simple mesenchymal cysts.

Treatment

Surgical excision, preferably complete when possible, is the treatment of choice. The principles of management are essentially those enumerated in the surgical treatment of hemangiomas. Treatment with sclerosing agents is ineffective, as is radiation therapy of the lesion.

A few patients, usually those with lesions situated in a paravertebral sulcus, may develop a chylothorax either spontaneously, as reported by Johnson and associates,99 or as a postoperative complication. The postoperative complication of a chylothorax is most likely to occur in the management of those lesions that extend below the diaphragm into the retroperitoneal area. Conservative management with closed-tube thoracostomy may be sufficient. In the patient reported by Johnson and associates,99 neither conservative management nor multiple attempted surgical ligations were successful in treating the chylothorax. Finally, the drainage ceased after a course of radiation therapy. If all of these therapies should fail, the use of pleuroperitoneal shunting with a double-valve Denver peritoneal shunt should be considered.

Milsom and associates141 and Miller138 have recorded successful use of this approach in a number of patients with unresolved chylothorax of varying causes. Murphy and colleagues148 used this technique in 16 patients, all but one of whom were infants, with satisfactory results in resolving persistent chylothoraces of varying causes in 75% of the cases. Two of the patients had acquired lymphangiomas, and the result was successful in both. These authors described the technique of placement and management of these shunts in excellent detail.

Prognosis

The isolated mediastinal lymphangioma is a benign lesion, and excellent results are obtained with complete or even partial excision. Progression is infrequent, and spontaneous malignant transformation is unrecorded. Park and colleagues155 reported five recurrences in 4 of their 12 patients (33%).

Lymphangiohemangioma

The lymphangiohemangioma is considered a subset of lymphangiomas and is a benign tumor composed of both lymphatic and vascular structures. Angtuaco and associates4 first described it as a lymphatic venous malformation occurring in the mediastinum, with Toye and associates212 reporting an additional case. Riquet and colleagues167 described another three cases. In two cases the left superior vena cava appeared to be involved, and the investigators postulated that these lesions were

associated with venous malformations. More recently, Xu236 reported a case with communication to the left innominate vein. Surgical excision is the treatment of choice.

associated with venous malformations. More recently, Xu236 reported a case with communication to the left innominate vein. Surgical excision is the treatment of choice.

Hemangioendothelioma

According to Hunt and Santa Cruz,90 the term hemangioendothelioma has been used to refer to benign and malignant vascular lesions. Recently the term has been used to define vascular lesions of intermediate malignancy as well as those that are malignant. The tumors of intermediate malignancy include kaposiform hemangioendothelioma (locally aggressive) as well as retiform hemangioendothelioma (rarely metastasizing) and composite hemangioendothelioma (rarely metastasizing). The malignant tumor is the epithelioid hemangioendothelioma. Of these tumors, only the epithelioid hemangioendothelioma has been described in the mediastinum. However, Iwami and colleagues93 described a case of a kaposiform hemangioendothelioma in the neck of a 7-month-old boy that extended into the superior mediastinum.

Epithelioid Hemangioendothelioma

Incidence

According to Weiss and Bridge,207 epithelioid hemangioendothelioma is a rare vascular tumor whose incidence is difficult to determine. These tumors have been reported in the liver, lung, and soft tissues. When they were first described in the lung, they were thought to be of epithelial origin and were called intravascular bronchioloalveolar tumors (IVBATs). Most mediastinal epithelioid hemangioendotheliomas are single case reports, but Suster and colleagues202 published a series of 12 patients. Ferretti and coworkers63 reported a case of a 79-year-old man with an epithelioid hemangioendothelioma of the superior vena and reviewed an additional 20 cases from the literature. Of these cases, most were in the anterosuperior mediastinum and five involved a major vein. Toursarkissian and colleagues211 reported a case of an epithelioid hemangioendothelioma arising in the anterior mediastinum from the innominate vein in a 62-year-old man. He was treated with surgery and radiation and remained free of disease after 4.5 years.

Clinical Features

In the series of Suster and colleagues,202 the patients ranged in age from 19 to 62 years, with a mean of 49.4 years, and the male–female ratio was 3:1. Seven of their patients presented with symptoms related to compression of surrounding structures, such as pain, cough, or shortness of breath. The other five were asymptomatic. In all 12 cases, the masses were located in the anterior mediastinum. Other reports include that of Mentzel and associates,137 who described two mediastinal tumors as part of a series of 30. Begbie and colleagues14 described one case occurring in a 50-year-old man with type IV Ehlers–Danlos syndrome who presented over an 8-year period with multiple mediastinal nerve palsies and chest pain. Campos and colleagues25 described a case in a 39-year-old woman who presented with a posterior mediastinal mass and a pleural effusion. The patient underwent surgery and was alive and well 9 years later.