INDICATIONS

The Merendino procedure can be employed when a limited resection of the distal esophagus and the GEJ is required.

These include the following.

Caustic nondilatable strictures of the distal esophagus

Caustic nondilatable strictures of the distal esophagus

Revisional surgery after multiple failed antireflux procedures

Revisional surgery after multiple failed antireflux procedures

Benign and semimalignant tumors at the esophagogastric junction

Benign and semimalignant tumors at the esophagogastric junction

Early adenocarcinoma of the distal esophagus or GEJ

Early adenocarcinoma of the distal esophagus or GEJ

In this chapter, we describe the patient selection and operative steps of the Merendino operation for early adenocarcinoma of the distal esophagus and GEJ in detail; nevertheless, most of the surgical technique is applicable to the other indications as well.

PREOPERATIVE PLANNING

PREOPERATIVE PLANNING

There are several proposed advantages specific to the Merendino procedure when compared with other competing procedures (total esophagectomy and endoscopic mucosal resection [EMR]) for treating early adenocarcinoma of the distal esophagus and the gastric cardia.

Potential advantages are as follows:

An oncologically adequate organ-preserving approach with low morbidity and mortality and superior long-term quality of life as compared with total esophagectomy.

An oncologically adequate organ-preserving approach with low morbidity and mortality and superior long-term quality of life as compared with total esophagectomy.

Full-thickness resection of the cancerous lesion with adequate tumor-free margins versus endoscopic resections in a piecemeal fashion.

Full-thickness resection of the cancerous lesion with adequate tumor-free margins versus endoscopic resections in a piecemeal fashion.

Removal of the entire esophageal segment with intestinal metaplasia to avoid recurrences and the need for life-long surveillance as seen after EMR.

Removal of the entire esophageal segment with intestinal metaplasia to avoid recurrences and the need for life-long surveillance as seen after EMR.

Regional en bloc lymphadenectomy providing locoregional control in patients with submucosal adenocarcinoma (T1b); these patients have a >20% chance of lymph node metastases.

Regional en bloc lymphadenectomy providing locoregional control in patients with submucosal adenocarcinoma (T1b); these patients have a >20% chance of lymph node metastases.

Combines esophageal reconstruction with an antireflux procedure controlling the underlying, usually severe reflux disease.

Combines esophageal reconstruction with an antireflux procedure controlling the underlying, usually severe reflux disease.

Evaluation of the patient with suspected early esophageal adenocarcinoma should include extensive diagnostic work-up with systematic biopsies aided by high-resolution endoscopy and endoscopic ultrasound to assess the depth of tumor invasion and the possible presence of multicentric disease. In patients with early cancer limited to the mucosa and without a multicentric tumor manifestation, an endoscopic mucosectomy can be performed to confirm the depth of tumor invasion. If a complete tumor removal (R0 situation) can be achieved, and the tumor is truly limited to the mucosa (T1a), with an endoscopic ultrasound showing no suspicious lymph nodes and a PET scan showing no evidence of distant metastasis, life-long close endoscopic surveillance may be justified, provided the patient is able and willing to undergo this follow-up and other unfavorable tumor characteristics are absent (e.g., angiolymphatic invasion, poor differentiation, ulceration, size >2 cm). All other patients including patients with intramucosal carcinoma with unfavorable tumor characteristics (as described above), multicentric lesions, submucosal tumor invasion, R1-mucosal resections, or recurrence after endoscopic mucosectomy are candidates for limited surgical resection. A computed tomography (CT) scan of the thorax and abdomen should be performed to evaluate for distant metastatic spread or lymph nodes outside the field of resection.

SURGERY

SURGERY

Surgical Considerations

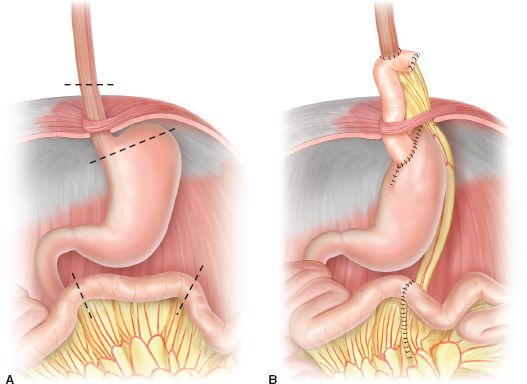

The goal of the operation is the full-thickness removal of the entire esophageal segment with Barrett’s mucosa and an additional en bloc regional lymphadenectomy. An antireflux procedure should be added to treat the underlying gastroesophageal reflux disease (Fig. 26.1A, B).

Surgical Technique/Sequence of Operative Steps

Positioning

The patient is positioned supine in a slight reverse Trendelenburg position on the operating room table, and at the time of induction a single dose of a broad-spectrum antibiotic is administered. The patient’s chest and abdomen are prepared with an antiseptic solution.

Exploration

The abdomen is entered via a generous bilateral subcostal incision. Although a midline incision affords excellent exposure of the upper abdomen as well, we prefer a transverse incision as this provides a wider exposure of the esophageal hiatus. The falciform ligament is divided and retractors are placed on the abdominal wall. The abdomen is then carefully explored to evaluate the extent of locoregional disease as well as the presence of unexpected peritoneal or hepatic metastases. Furthermore, at this point, the adequacy (length) of the jejunal mesentery for the intrathoracic pull-up should be assessed.

Figure 26.1 A: Limited resection of the distal esophagus, esophagogastric junction, and proximal stomach. B: Reconstruction by interposition of a pedicled isoperistaltic jejunal segment.

Dissection of the Diaphragmatic Hiatus and the GEJ

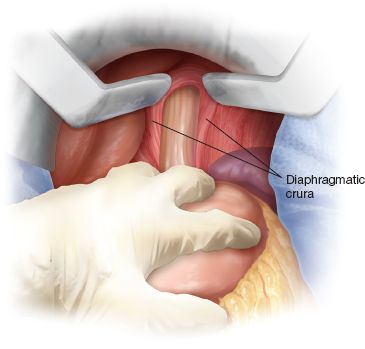

First, the greater curvature of the stomach is mobilized and the bursa omentalis is entered by dividing the greater omentum from the colon through the avascular plane using the electrocautery. Then, the gastrohepatic ligament at the lesser omentum is dissected. Here, running beside the hepatic branch of the vagus nerve, a sizeable hepatic branch of left gastric artery can be encountered in fewer than 5% of patients, which may comprise the majority of arterial inflow to the left lateral segment of the liver. For this reason, it should be preserved by ligating the minor branches providing the lesser curvature of the stomach while conserving the main branch. Further dissection from the right side toward the esophageal hiatus and the division of the gastrophrenic ligament frees the right diaphragmatic crus. From the left side, the short gastric vessels are divided, the left diaphragmatic crus is identified (Fig. 26.2). After circular dissection of the abdominal esophagus, a Penrose drain is slung around the esophagus to provide retraction for the further dissection. The vagal nerves can be divided at this point. Preservation of the vagal nerves compromises lymphadenectomy and should thus only be attempted in patients with mucosal cancer or high-grade neoplasia. The diaphragmatic hiatus is widely opened by incision of the left diaphragmatic crus. This provides good access to the lower posterior mediastinum.

Figure 26.2 Complete dissection of the distal esophagus and the diaphragmatic crura.