Mediastinal Parathyroid Tumors

Raja R. Gopaldas

David C. Rice

Ann-Greth Bondeson

Norman W. Thompson

The parathyroid glands, discovered in 1880 by Ivar Sandstrom, a Swedish medical student, were the last major organs to be recognized in humans. According to Carney,11 the discovery attracted little attention until its association with severe bone disease was realized in the early 1900s. The first documented excision of a mediastinal parathyroid adenoma occurred in 1932, when Charles Martell, a sea captain, underwent his seventh operation for persistent hyperparathyroidism (HPT).4 Although a small portion of the adenoma was left in place and another portion transplanted, he developed tetany, which required intravenous calcium replacement. Six weeks later, following removal of an obstructing ureteral calculus, he died of hypocalcemia. Although symptomatic mediastinal parathyroids are exceedingly rare, in one series accounting for only 1% of operations for parathyroid disease,91 they can present diagnostic and therapeutic challenges. Most patients with symptomatic mediastinal parathyroid disease have already been subjected to a cervical parathyroidectomy. Persistent or recurrent disease usually prompts further workup, which typically localizes the missing gland. Persistent HPT usually occurs because of a missed abnormal gland, and missed glands are ectopic in up to 60%, as noted by Gough.33 A thoracic surgeon is involved in the management of parathyroid disease primarily because of persistent HPT with a source localized to the mediastinum, based on imaging studies. The management of primary HPT (PHPT) has changed dramatically in recent years. Traditional cervical exploration with bilateral four-gland assessment has given way in many practices to minimally invasive parathyroidectomy (MIP), where the offending gland or glands are identified using preoperative localization imaging and a targeted resection is performed. This has resulted in the much more widespread use of preoperative imaging studies, a practice once discouraged, which has consequently led to the more frequent identification of ectopic glands prior to cervical exploration. Nearly 25% of parathyroid glands are ectopic, and 2% are not accessible to standard cervical surgical approaches because they are located deep in the mediastinum or high in the neck, as pointed out by O’Herrin.71 Although sternotomy or posterolateral thoracotomy has traditionally been the approach for mediastinal parathyroid adenomas, more recently minimally invasive resection of these glands has been adopted, as described below.

Anatomic Considerations

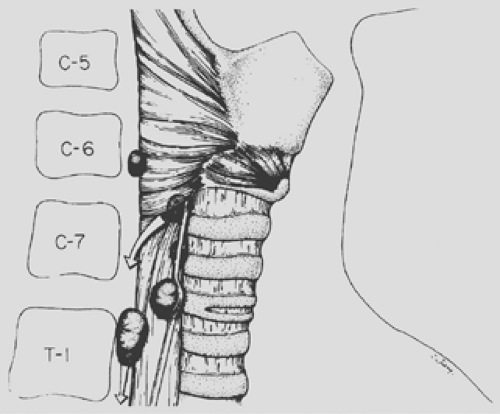

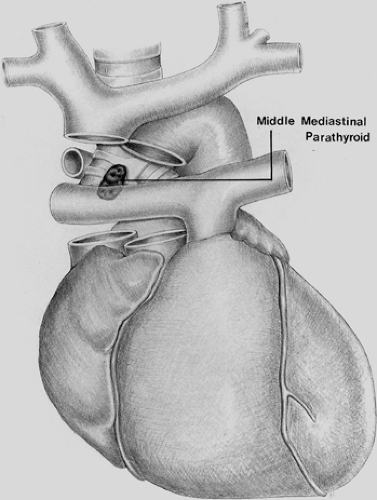

The incidence of ectopic mediastinal parathyroid glands is reported to range between 1% and 20%. This wide variation is likely secondary to differences in the definition of what actually constitutes a mediastinal location. Some authors consider all glands inferior to the superior border of the manubrium to be “mediastinal,”28 whereas others apply this classification only to mediastinal glands inaccessible through a cervical incision.87,119 As noted by Thompson,113 deeply seated mediastinal glands account for no more than 1% to 3% of all parathyroid tumors, with most being ectopic inferior parathyroid glands. Inferior glands are derived from the parathyroid tissue of the third branchial pouch (parathyroid III). In nearly all cases, the arterial supply is derived from a branch of the internal mammary artery, whereas normally located inferior parathyroid glands or those located in the upper mediastinum are typically supplied by branches of the inferior thyroid artery. Paraesophageal or retroesophageal parathyroid glands always arise from enlarged superior glands (parathyroids IV) that have descended further into their acquired location in the posterior mediastinum (Figs. 200-1 and 200-2). A normal cervical blood supply is maintained from a branch of the inferior thyroid artery, which can help guide the surgeon to the location of the gland. These glands can usually be excised during a neck exploration. On occasion, an ectopically located deep mediastinal parathyroid tumor, if contained within a thymus gland that can be mobilized with careful traction from above, can be removed through a neck excision.

Clinical Considerations

Because deep mediastinal parathyroid tumors are uncommon (1%–3%), most surgeons in the past had not recommended localization studies prior to a routine cervical exploration for PHPT; indeed, the possibility of an ectopic mediastinal gland was usually considered only after cervical exploration had failed to identify an adenoma. The development of advanced nuclear imaging techniques has now favored routine use of such studies for PHPT. Although no single study or combination of studies approaches 100% sensitivity, the missing gland can be localized fairly consistently with a combination of technetium-99m (99Tc) sestamibi scans and spiral computed tomography (CT). A crucial step before undertaking a reoperation in the mediastinum is to analyze operative and pathologic reports from the previous cervical exploration to determine whether the “missing” gland is most likely to be superior or inferior in origin, because that simple fact can determine where the search should be directed. If four normal glands were previously identified with certainty and the patient has biochemical proof of HPT, the

disease is most likely due to a supernumerary gland in the mediastinum. If an inferior gland was not found after a thorough exploration—including intrathyroidal, carotid sheath, and upper thymic locations—the tumor is likely to be deep within the anterior mediastinum. As reported by Dubost and Bouteloup28 as well as by Dubost,29 Proye,79 and Thompson113 and associates, approximately 80% of all deep mediastinal parathyroid tumors are ectopic inferior parathyroid glands located in the anterior mediastinum and are usually situated within or in close contact with the thymus secondary to embryologic displacement. The common origin of the thymus and inferior parathyroid gland from the third branchial pouch is the embryologic basis for this intimate association. In Russell and associates’91 series of 37 parathyroid adenomas removed from the anterior mediastinum, 26 were associated with the thymus. Similar experiences have been reported by Rothmund87 and Thompson.113

disease is most likely due to a supernumerary gland in the mediastinum. If an inferior gland was not found after a thorough exploration—including intrathyroidal, carotid sheath, and upper thymic locations—the tumor is likely to be deep within the anterior mediastinum. As reported by Dubost and Bouteloup28 as well as by Dubost,29 Proye,79 and Thompson113 and associates, approximately 80% of all deep mediastinal parathyroid tumors are ectopic inferior parathyroid glands located in the anterior mediastinum and are usually situated within or in close contact with the thymus secondary to embryologic displacement. The common origin of the thymus and inferior parathyroid gland from the third branchial pouch is the embryologic basis for this intimate association. In Russell and associates’91 series of 37 parathyroid adenomas removed from the anterior mediastinum, 26 were associated with the thymus. Similar experiences have been reported by Rothmund87 and Thompson.113

Recent reports of patients who have undergone reoperation for persistent or recurrent HPT are consistent with older series.12,65 An extensive review conducted by Jaskowiak and associates41 on patients who underwent reoperative parathyroid surgery revealed that the most common location for an ectopic parathyroid gland was in the tracheoesophageal groove, accounting for 27% of cases. Similarly, Shen et al.100 evaluated 102 patients with persistent or recurrent HPT and found ectopic glands to be responsible in 53% of cases. Of the ectopic glands, 28% were paraesophageal, 26% mediastinal (nonthymic), 24% intrathymic, 11% intrathyroidal, 9% carotid sheath, and 2% high cervical. In another more recent series of 50 patients who underwent reoperative parathyroid surgery, Gough33 likewise found that ectopic glands were present in 60% of cases. The ectopic location was intrathyroidal in 10 patients, intrathymic in 9, and posterior mediastinal in 4. In contrast to these studies, Thompson and colleagues112 reported 124 patients undergoing reoperation for parathyroid disease at the Mayo Clinic but found the cause to be ectopic glands in only 26 (21%) patients. In these cases, 8 (31%) were mediastinal in location.112 Other rare ectopic locations, such as the aortopulmonary window, have been noted (Fig. 200-3).

Thompson114 and coworkers113 have noted that parathyroid tumors of the superior glands migrate into the upper posterior part of the visceral compartment of the mediastinum in approximately 40% of cases. The larger the tumor, the more likely this is to occur; this probably results from a combination of factors, including gravity, deglutition, negative chest pressure, and an unobstructed pathway into the prevertebral space.

Phitayakorn and McHenry76 reported on 231 patients operated on for HPT. Ectopic glands were found in 37 (16%) patients overall, and in 34 (17%) of 195 patients with primary HPT (PHPT). Ectopic glands were superior in 14 (38%) and inferior in 23 (62%). For inferior glands, the thymus accounted for the commonest location (30%), followed by the anterosuperior mediastinum (22%), thyroid (22%), and thyrothymic ligament (17%). As reported by Clark,16 the majority of mediastinal thymic parathyroids can be resected through a cervical approach. Of 285 consecutive patients operated on for HPT, 64 (22%) patients had “mediastinal” parathyroid tumors. Of these, 20 (38%) patients had persistent or recurrent disease. The majority of patients (81%) had ectopic glands in the anterior mediastinum; in 87% of patients, resection was accomplished via a cervical approach. Recent awareness of the relatively frequent

occurrence of “mediastinal” glands, as noted by preoperative localization studies, has decreased the risk of failed parathyroid operations. As noted by McIntyre,59 the most common reason for failure of the primary operation for HPT is a mediastinal parathyroid.

occurrence of “mediastinal” glands, as noted by preoperative localization studies, has decreased the risk of failed parathyroid operations. As noted by McIntyre,59 the most common reason for failure of the primary operation for HPT is a mediastinal parathyroid.

Pathology

Benign Adenomas and Hyperplasia

The relative frequency of parathyroid lesions leading to PHPT is somewhat controversial; however, adenomas are the commonest cause, accounting for 75% to 80% of cases; benign hyperplasia is responsible in 10% to 15%; and parathyroid carcinoma in less than 5%. The pathology of mediastinal parathyroid lesions does not differ from that of cervical parathyroid glands. Adenomas are usually solitary, average 0.5 to 5.0 g in weight, and characteristically are well encapsulated, soft, and tan to red in color. Although two or more adenomas may be present within the same or different glands, nodular hyperplasia must always be ruled out when more than one adenoma is identified. The typical morphologic appearance for adenoma includes the presence of a distinct capsule, about which a rim of compressed normal parathyroid tissue may be present. There is typically little or no stromal fat within an adenoma, in contrast to the admixture of fat in the normal gland and scant fat cells in hyperplastic glands. When a functional adenoma exists, the unaffected glands will be of normal size or even slightly smaller because of suppression secondary to elevated parathormone and calcium. Primary hyperplasia may occur sporadically or as part of the multiple endocrine neoplasia syndromes (MEN I and MEN IIa). Although typically hyperplasia affects all four glands, the degree of enlargement may be asymmetric. The combined weight of all glands rarely exceeds 1.0 g. Hyperplasia may be either diffuse or nodular. Hyperplastic cells may be arranged in a variety of patterns—solid sheets, nests, trabeculae, or follicles—but a characteristic finding is the presence of scant fat cells dispersed throughout the hyperplastic area. Hyperplasia of secondary HPT affects mediastinal parathyroid glands to the same extent as it does glands in normal locations, and the cellular features mimic those seen with primary hyperplasia. Supernumerary glands in patients with secondary HPT occur in the anterior mediastinum in more than 50% of cases. Because such glands are usually within the upper thymus, cervical thymectomy has become a routine part of the surgical treatment of both primary and secondary hyperplasia. Supernumerary glands are just as prone to adenomatous change or hyperplasia as their normally located counterparts. In PHPT, thymectomy is performed routinely only when four normal glands have been identified or an inferior gland has not been detected after finding three other normal glands despite complete cervical exploration. Thyroid lobectomy is usually indicated only for a missing superior parathyroid gland; thymectomy hence precedes thyroid lobectomy for missing inferior parathyroid glands.

Parathyroid Cysts

Mediastinal parathyroid cysts can vary in size from less than 1 cm to 12 cm or larger. Most cysts are thin-walled, translucent

and unilocular. Microscopically the cysts are composed of a thin fibrous wall lined with cuboidal or columnar cells interspersed with normal parathyroid cells. Occasionally larger masses of normal parathyroid tissue may be present. In their excellent review of 94 patients with parathyroid cysts, Shields and Immerman102 noted cysts to be functional in 41%. Parathyroid cysts were noted to occur most commonly (59.5%) in the anterosuperior space (retrosternal and above the innominate vessels), followed by the retrotracheal area in 27.6% and the prevascular space (retrosternal, below the innominate vessels) in 12.7%. Similarly, Calandra and associates’9 review of parathyroid cysts found that 50% were associated with HPT. The majority of these (90%) were located in the neck, however. Although several theories have been proposed for their origin, the hypothesis that these are secondary to cystic degeneration of the gland is widely accepted.1,21,102,103 The management of hyperfunctioning mediastinal parathyroid cysts is similar to that of mediastinal parathyroid adenomas. Prior to modern imaging techniques, preoperative diagnosis of mediastinal parathyroid cysts was rarely made. Parathyroid scintigraphy has been useful in determining if a mediastinal cyst is of parathyroid origin. Biopsy of the cyst wall is not recommended; it is frequently not helpful because the parathyroid tissue is not homogeneous. Rather, the cyst wall contains multiple nests of parathyroid tissue. Fine-needle aspiration of cyst contents is diagnostic, however, if elevated parathyroid hormone (PTH) is documented. Nonfunctioning cysts have been reported to have PTH levels in the cystic fluid ranging from 600 to 416,650 pg/mL, and between 2 and 6 million pg/mL with functioning cysts, as noted by Katz,45 Spitz,107 and Ramos-Gabatin and associates.81 Irrespective of the fluid content, if the patient presents with HPT and the localization studies indicate the parathyroid cyst to be hyperfunctioning, surgical resection is warranted. The approach used will be dictated by the location of the lesion. Meticulous handling of these usually thin-walled cysts is essential to accomplish complete removal of the cyst, as rupture of the cyst may distort the dissection planes, making resection difficult.

and unilocular. Microscopically the cysts are composed of a thin fibrous wall lined with cuboidal or columnar cells interspersed with normal parathyroid cells. Occasionally larger masses of normal parathyroid tissue may be present. In their excellent review of 94 patients with parathyroid cysts, Shields and Immerman102 noted cysts to be functional in 41%. Parathyroid cysts were noted to occur most commonly (59.5%) in the anterosuperior space (retrosternal and above the innominate vessels), followed by the retrotracheal area in 27.6% and the prevascular space (retrosternal, below the innominate vessels) in 12.7%. Similarly, Calandra and associates’9 review of parathyroid cysts found that 50% were associated with HPT. The majority of these (90%) were located in the neck, however. Although several theories have been proposed for their origin, the hypothesis that these are secondary to cystic degeneration of the gland is widely accepted.1,21,102,103 The management of hyperfunctioning mediastinal parathyroid cysts is similar to that of mediastinal parathyroid adenomas. Prior to modern imaging techniques, preoperative diagnosis of mediastinal parathyroid cysts was rarely made. Parathyroid scintigraphy has been useful in determining if a mediastinal cyst is of parathyroid origin. Biopsy of the cyst wall is not recommended; it is frequently not helpful because the parathyroid tissue is not homogeneous. Rather, the cyst wall contains multiple nests of parathyroid tissue. Fine-needle aspiration of cyst contents is diagnostic, however, if elevated parathyroid hormone (PTH) is documented. Nonfunctioning cysts have been reported to have PTH levels in the cystic fluid ranging from 600 to 416,650 pg/mL, and between 2 and 6 million pg/mL with functioning cysts, as noted by Katz,45 Spitz,107 and Ramos-Gabatin and associates.81 Irrespective of the fluid content, if the patient presents with HPT and the localization studies indicate the parathyroid cyst to be hyperfunctioning, surgical resection is warranted. The approach used will be dictated by the location of the lesion. Meticulous handling of these usually thin-walled cysts is essential to accomplish complete removal of the cyst, as rupture of the cyst may distort the dissection planes, making resection difficult.

Other morphologic variants include partially calcified adenomas, which are uncommon but noteworthy because they can be seen on plain chest radiographs. A single calcified nodule found in the anterior mediastinum in a hypercalcemic patient should raise suspicion for an adenoma. Large adenomas with calcifications have contained areas of hemorrhagic necrosis and scarring. Some of these have been associated with a surrounding desmoplastic reaction induced by an inflammatory reaction in the capsule. These adenomas have been found in both the neck and the mediastinum and can be initially misinterpreted as parathyroid carcinoma because of their capsular thickening and local adherence. However, microscopically there is no evidence of capsular invasion.

Rarely, as noted by Jordan and coworkers,42 hemorrhagic infarction of a parathyroid adenoma can cause rupture of the capsule and massive extracapsular hemorrhage. Numerous researchers—including Capps,10 Stocks and Hartley,108 Berry,5 Santos,92 Sarfati,94 Simic,104 and Nakajima64 and their associates—have reported the occurrence of this complication. To the unsuspecting, this can be misinterpreted as a cardiac event or a dissecting aortic aneurysm. The triad of acute neck swelling, hypercalcemia, and ecchymosis of the neck or chest is strongly suggestive of this entity.

Parathyroid Carcinoma

Occasionally, parathyroid carcinoma can arise in the mediastinum. These tumors present as gray–white irregular masses that may often exceed 10 g in weight and generally affect a single parathyroid gland. A parathyroid carcinoma should be suspected if the serum calcium is greater than 14 mg/dL; this is the most important finding that distinguishes a carcinoma from adenoma or hyperplasia, as pointed out by Delaney.22 The circulating concentration of PTH in parathyroid carcinoma is in the range of 3 to 10 times above the upper limits of normal, as noted by Shane and coworkers.99 Alkaline phosphatase is often elevated in patients with parathyroid carcinoma.35 Cohn18 noted that, in contrast to patients with adenoma or hyperplasia, patients with parathyroid carcinoma tend to be younger and more symptomatic The most frequent complaints are fatigue, weakness, weight loss, anorexia, nausea, vomiting, polyuria, and polydipsia. Cohn and Silen19 and Dubost and colleagues28 have reported that these symptoms can represent metastatic spread from a primary tumor in the neck. However, example of a parathyroid carcinoma arising in ectopic or supernumerary mediastinal parathyroid gland in the superior portion of the visceral compartment has been reported by Kelly46 and Lee and Hutcheson.51 Pezzullo and coworkers75 recently reported a large parathyroid carcinoma that mimicked a large substernal goiter on physical and radiologic examination. Histologically, the neoplastic cells may be of variable size and shape but may also be remarkably uniform and not dissimilar from normal parathyroid cells. There is general agreement that a diagnosis of carcinoma based on cytologic detail alone is unreliable and that local invasion and metastasis constitute the only reliable criteria of malignancy. Parathyroid carcinoma is generally considered to be a slow-growing malignancy; however, its clinical course can be quite variable.86 En bloc excision including surrounding thymic and nodal tissue, mediastinal fat, and, if adherent, pericardium is indicated. In patients who undergo routine parathyroidectomy because carcinoma is not suspected, local recurrence is over 50%, in contrast to 10% to 33% after planned en bloc resection.48 For cervical parathyroid carcinoma, adjuvant external beam radiation has been shown to reduce local recurrence. Overall 5-year survival is reported to be 86%.38

Localization Studies

The introduction of 99mTc sestamibi by Coakley17 had a significant impact on the field of parathyroid surgery and replaced the traditional thallium-201 (201Tl) scans with a better technique and image quality. Localization of the gland had always been an enigma for surgeons, and the availability of these scans has facilitated the precise preoperative localization of the glands, thereby avoiding unnecessary dissection. All patients who have had a failed parathyroid operation should undergo preoperative noninvasive localization procedures before proceeding with another exploration, particularly if a mediastinal procedure is anticipated. Rothmund,87 Edis,30 Norton,66 and Wang119 and their associates reported the failure rate for mediastinal exploration to be 30% to 36% in those cases where localization studies had not identified a tumor before the operation was undertaken. Although localization studies have been used in the past mainly in

cases of persistent or recurrent HPT, the increasing use of minimally invasive parathyroidectomy and the consequent need to locate the offending gland prior to surgery has greatly increased the use of preoperative imaging. Moriyama63 reported a case where preoperative imaging helped in selective localization of the tumor to the mediastinum, thereby avoiding unnecessary cervical dissection.

cases of persistent or recurrent HPT, the increasing use of minimally invasive parathyroidectomy and the consequent need to locate the offending gland prior to surgery has greatly increased the use of preoperative imaging. Moriyama63 reported a case where preoperative imaging helped in selective localization of the tumor to the mediastinum, thereby avoiding unnecessary cervical dissection.

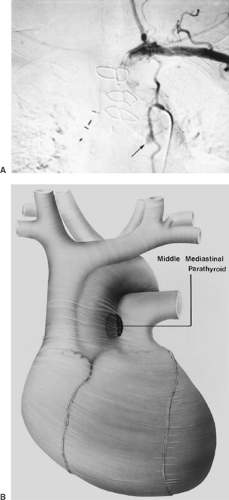

The two most commonly used imaging techniques for mediastinal parathyroid tumors are CT (Fig 200-4) and 99mTc sestamibi (99mTc-methoxyisobutylisonitrile [MIBI]) scintigraphy. The advantage of sestamibi is its prolonged retention in the parathyroid gland compared with the early washout of the same in the thyroid tissue, which help to localize the parathyroid glands in the neck. The value of these studies has been pointed out by Norton,66 Sarfati,93,94 Levin,52 Curly,20 and McHenry57 and their associates, among others. Rubello and colleagues89 have suggested a single-day imaging protocol of 99mTc pertechnetate-MIBI subtraction scintigraphy and MIBI single-photon emission computed tomographic (SPECT)/CT image fusion for localization of mediastinal parathyroid adenomas (Fig. 200-5). In a small series of six patients, Doppman and colleagues25 found SPECT CT to be more accurate than either CT or magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) at differentiating aortopulmonary adenomas from the more commonly occurring adenomas in the anterior mediastinum (Fig. 200-6). The precise localization of mediastinal adenomas is of utmost importance, especially in the era of minimally invasive techniques. Selective venous sampling using the intact serum parathyroid hormone immunoradiometric assay should be performed only when noninvasive localization has failed to demonstrate a “missing” parathyroid tumor. Several techniques of selective venous sampling for localizing the missing parathyroid tumor were described by Reitz84 and O’Riordan.73 Although not accurate in pinpointing the exact location of the tumors, they will regionalize the source of hormone to the mediastinum if a tumor is present there. Before the advent of modern imaging techniques, Scholz and associates97 had suggested that localization of hyperfunctioning parathyroid tissue by selective venous catheterization with sampling of intact-PTH (iPTH) at various cervical and intrathoracic levels was essential to the success of the operation. With the advent of better scintigraphic imaging technology utilizing 99Tc sestamibi, selective venous sampling is not performed unless scintigraphic imaging is equivocal.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree