CHAPTER 40 Mediastinal Anatomy and Mediastinoscopy

MEDIASTINAL ANATOMY

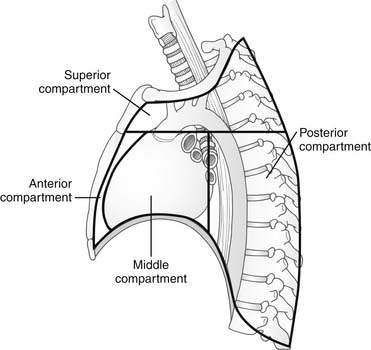

A classic description divides the mediastinum into four compartments: superior, anterior, middle, and posterior (Fig. 40-1). The superior mediastinum includes all structures from the thoracic inlet superiorly to a line drawn from the lower edge of the manubrium to the lower edge of the fourth thoracic vertebra. The inferior mediastinum, which lies inferior to this line, is subsequently divided into the anterior, middle, and posterior compartments. The boundary between the anterior and middle compartments is the anterior pericardium; between the middle and posterior compartments is the posterior aspect of the tracheal bifurcation, pulmonary vessels, and pericardium. Another system combines the anterior and superior compartments into an anterosuperior compartment, thus creating three compartments. With either of these systems, structures can be contained within two separate compartments. For example, in the four-compartment model, the upper portions of the trachea and esophagus are contained within the superior mediastinum; the lower portions are contained within the middle and posterior mediastinum.

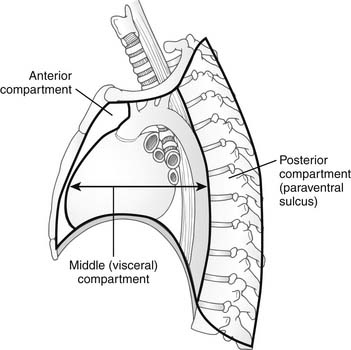

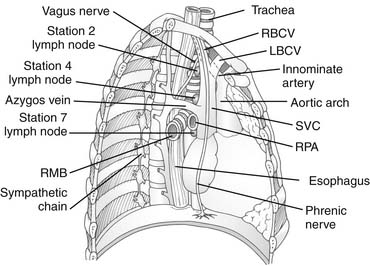

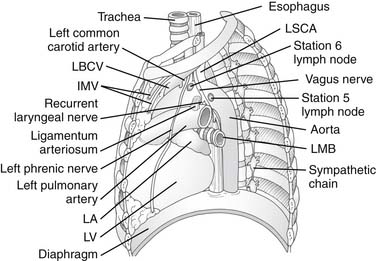

Shields proposed a simpler three-compartment model consisting of an anterior compartment, middle (or visceral) compartment, and posterior compartment (paraventral sulcus) (Fig. 40-2).1 All three compartments are bounded inferiorly by the diaphragm, laterally by the pleural space, and superiorly by the thoracic inlet. The anterior compartment is bounded anteriorly by the sternum and posteriorly by the great vessels and pericardium and contains the thymus, internal mammary vessels, areolar and adipose tissue, and potentially pathologic structures such as ectopic parathyroid tissue or a retrosternal goiter. The middle mediastinum is bounded posteriorly by the ventral surface of the thoracic spine; it occupies the entire thoracic inlet and contains the majority of mediastinal structures, namely, the great vessels, heart, pericardium, trachea, proximal main-stem bronchi, vagus nerves, phrenic nerves, esophagus, thoracic duct, descending aorta, and azygos venous system. The posterior compartment (paraventral sulcus) consists of potential spaces along the thoracic vertebrae that contain the sympathetic chain, proximal portions of the intercostal neurovascular bundles, thoracic spinal ganglia, and distal azygos vein. Whereas some anatomists may argue that the paraventral sulci are not truly a mediastinal space, they often harbor disease that is classically considered in the posterior mediastinum (neurogenic tumors). Detailed sagittal views of mediastinal anatomy are depicted in Figures 40-3 and 40-4.

POTENTIAL SPACES IN THE MEDIASTINUM

For ease of communication in describing pathologic change, most commonly lymph node enlargement, several potential mediastinal spaces are described. The pretracheal space is a triangular space bounded anterolaterally by the superior vena cava and right brachiocephalic vein on the right, the aorta and pericardium on the left, and the trachea posteriorly. The pretracheal space is contiguous inferiorly with the subcarinal space, which is bounded superiorly by the carina, laterally by the main-stem bronchi, anteriorly by the pulmonary artery, and posteriorly by the esophagus (see Fig. 40-3). The pretracheal and subcarinal spaces are routinely explored in mediastinoscopy. The aortopulmonary window is the space bounded superiorly by the aortic arch, medially by the trachea and esophagus, inferiorly by the pulmonary artery, and laterally by the pleura. This space contains lymph nodes, the ligamentum arteriosum, and the left recurrent laryngeal nerve (see Fig. 40-4). Routine cervical mediastinoscopy does not access this space, but anterior mediastinotomy (Chamberlain procedure), extended cervical mediastinoscopy, and thoracoscopy or thoracotomy provide access to the aortopulmonary window.

MEDIASTINAL LYMPH NODE ANATOMY

Since the adoption of a common thoracic regional lymph node classification by the American Joint Committee and the Union Internationale Contre le Cancer in 1997, the system, often referred to as the Mountain and Dresler chart, has found widespread acceptance (Fig. 40-5).2 This system classifies lymph nodes into 14 stations, of which stations 1 through 9 are contained within the mediastinal pleura and thus are mediastinal lymph nodes. Lymph node stations 2, 4, and 7, depicted in Figure 40-3, are the only nodal stations accessible by standard mediastinoscopy; stations 5 and 6, depicted in Figure 40-4, require an alternative approach like extended mediastinoscopy or anterior mediastinotomy.

INDICATIONS FOR MEDIASTINAL LYMPH NODE ASSESSMENT

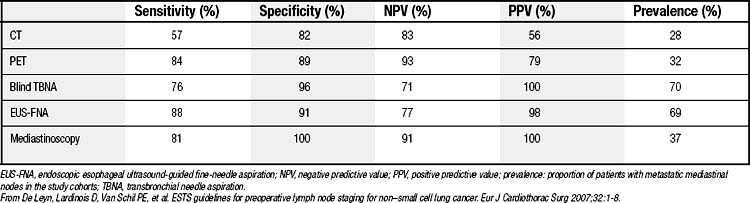

The most common indication for assessment of mediastinal lymph nodes remains non–small cell lung cancer. Other indications include mediastinal lymphadenopathy of unknown etiology, mediastinal masses, primary tracheal tumors, and occasional esophageal tumors. The increasing use of modern imaging techniques including high-resolution computed tomography and positron emission tomography has led to a more selective strategy in invasive mediastinal lymph node assessment, especially for stage I non–small cell lung cancer. This stems from the fact that the sensitivity and negative predictive value of positron emission tomography approach those of cervical mediastinoscopy in a review of the literature (Table 40-1).3,4

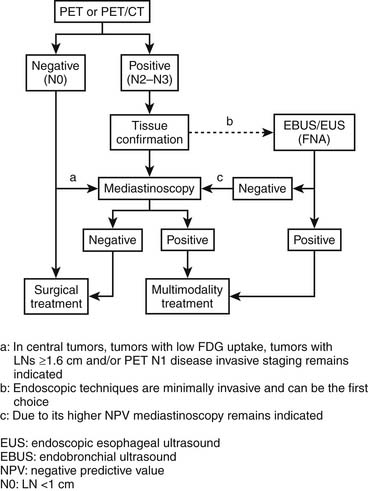

The European Society of Cardiothoracic Surgery has provided recommendations for mediastinal lymph node assessment in preoperative staging of non–small cell lung cancer (Fig. 40-6).4

In addition, a cost-effectiveness analysis concluded that patients with clinical stage I lung cancer staged by computed tomography and positron emission tomography benefit little from mediastinoscopy.5 Other views of the most efficient strategy for staging of the mediastinum exist, and results from ongoing trials of cervical mediastinoscopy will further refine its indications in the near future. An argument offered by some for routine cervical mediastinoscopy in non–small cell lung cancer is maintenance of familiarity with the technique and its minimal morbidity in experienced hands, but maintenance of familiarity with a procedure that is rarely needed is a questionable defense for its routine use.

SURGICAL TECHNIQUE

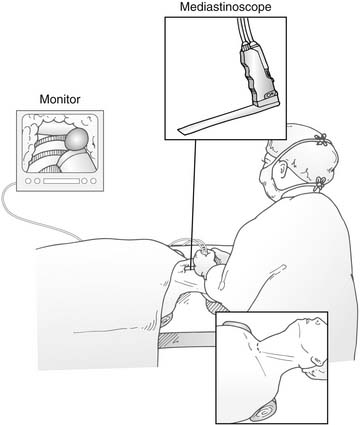

Standard cervical mediastinoscopy involves access of the middle mediastinal structures through a lighted hollow metal mediastinoscope introduced through a cervical incision. Recent innovations use fiberoptics and a television monitor to allow all members of the surgical team to see the anatomy simultaneously. This addition probably enhances safety and speeds the learning curve for trainees. Large-bore venous access is warranted, and many anesthetists routinely place a right radial arterial catheter to monitor blood pressure and to watch for innominate artery compression during the procedure. Alternatively, some centers use a pulse oximeter probe on the right hand. Once patients are intubated, they are placed in the supine position with the neck gently hyperextended, but not so much that the head is “floating,” with an inflatable bag or rolled blanket placed behind the shoulders (Fig. 40-7).

< div class='tao-gold-member'>

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree