LEARNING OBJECTIVES

Learning Objectives

The student will be able to define the categorization of clinical pneumonia into community-acquired versus hospital-acquired pneumonia.

The student will be to describe the epidemiology of community-acquired versus hospital-acquired pneumonia.

The student will be able to recognize the common symptoms and signs of infectious pneumonia.

The student will be able to summarize the general principles of treatment of infectious pneumonia.

Although the symptoms and signs of infectious pneumonia were known and described by both patients and physicians in ancient times, the pathophysiology of pneumonia has only recently become clear. Consequently, effective treatment for bacterial pneumonia has been available for <100 years. The presence of bacteria in the respiratory tissue of patients with pneumonia was first identified in the latter half of the nineteenth century. However, without effective antimicrobial medications, the morbidity and mortality from pneumonia remained high during the first half of the twentieth century. Thus, prior to the availability of penicillin in the 1940s, 80% of patients in the United States with bacteremic pneumococcal pneumonia died. The mortality rate dropped to approximately 20% after the clinical introduction of penicillin, and the current mortality rate for community-acquired pneumonia is approximately 4%. Even so, pneumonia remains the most common cause of infectious death in the United States. Also of concern, many of the once highly effective antimicrobial medications for the treatment of pneumonia have been rendered ineffective with the emergence of resistant organisms.

In clinical practice, infectious pneumonia is divided into two main categories: (1) community-acquired pneumonia (CAP); and (2) hospital-acquired pneumonia (HAP). Community-acquired pneumonia can be defined as any infectious pneumonia in patients who are not hospitalized, or who have been hospitalized for <48 hours and not admitted to a hospital or extended health care facility in the past 90 days. By contrast, hospital-acquired pneumonia includes pneumonias that develop in patients who have been hospitalized for >48 hours, or who have been admitted to hospitals or extended health care facilities in the previous 90 days. Categorizing pneumonia as either CAP or HAP is useful because the spectrum of likely infectious pathogens differs significantly between the two groups. Management decisions can thereby be tailored to the most likely pathogens in each setting, even before the potential isolation of a specific pathogen. Immunosuppressed persons are at special risk of developing pneumonia due to any of the organisms commonly associated with CAP or HAP, as well as to opportunistic pathogens that usually do not cause disease among immunocompetent patients.

MANAGEMENT OF COMMUNITY-ACQUIRED PNEUMONIA

The first step in management of CAP is prevention. Vaccines against three common CAP pathogens are available: influenza, Streptococcus pneumonia (pneumococcus), and Haemophilus influenzae. Seasonal influenza vaccination is recommended for children who are 6-23 months old, adults > 50 years of age, healthcare providers, and certain other high-risk individuals including those with significant medical comorbidities. Likewise, pneumococcal vaccination is recommended for adults ≥65 years of age and for certain other high risk individuals, again including those with significant medical comorbidities.

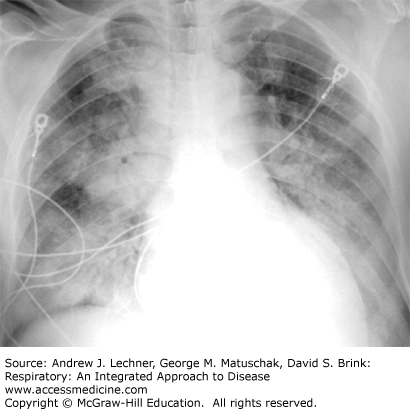

Evaluation of a patient with suspected CAP starts with a comprehensive history including the presence or absence of fever, chills, malaise, cough, sputum production, dyspnea, and chest pain among other symptoms. Physical findings compatible with pneumonia include tachypnea, increased tactile fremitus, dullness to percussion, and inspiratory crackles or egophony on chest auscultation (Chap. 14). Opacities or parenchymal consolidation on thoracic imaging studies support the clinical diagnosis (Figs. 35.1, 35.2; see also Chap. 15).

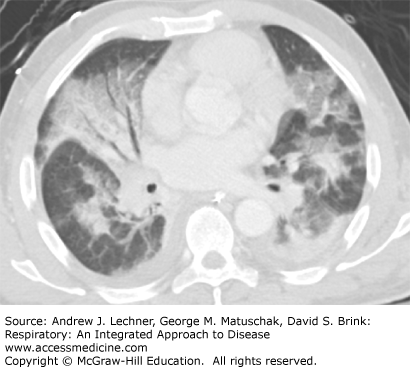

FIGURE 35.2

Chest CT scan of the same patient depicted in Fig. 35.1 at the mid-chest level demonstrating bilateral patchy air space opacities in a patient with CAP. Air bronchograms are notable on the patient’s right side. Small bilateral pleural effusions are also present.

Because CAP by definition involves patients who develop pneumonia outside of a health care setting, one of the first steps in management is to decide the most optimal setting to provide safe treatment for the patient. For example, will outpatient treatment suffice, or does the patient need to be admitted to the hospital and if so, is intensive care unit (ICU) admission warranted? These questions are best answered by the initial assessment of severity of a patient’s pneumonia. In this regard, a helpful tool is the CURB-65 score which is a refinement of an instrument originally set forth by the British Thoracic Society. CURB-65 is an acronym for the five components of the score: Confusion, Blood urea nitrogen level, Respiratory rate, Blood pressure, and age of 65 years or older (Table 35.1).

The risk of mortality increases with increasing values of a CURB-65 score. Thus, patients with a CURB-65 score of 0 or 1 are considered at low risk for complications and can be usually considered for ambulatory treatment. In this context, however, other clinical factors such as the patient’s living environment and social support, as well as comorbidities need to be taken into account to assure the safety and efficacy of treatment. Admission to the hospital is recommended when the patient’s CURB-65 score is ≥2 and many patients with scores of ≥3 will require admission to the ICU. The American Thoracic Society (ATS) and Infectious Disease Society of America (IDSA) have also developed consensus-related criteria for Severe CAP (Table 35.2). By these criteria, patients with ≥ one major criteria or ≥ three minor criteria require ICU admission.

| Major Criteria |

| Invasive mechanical ventilation |

| Septic shock with the need for vasopressors |

| Minor Criteria |

| Respiratory rate ≥30 breaths/min |

| Pao2/FIo2 ratio ≤250 (see Chap. 28) |

| Multilobar infiltrates on chest imaging |

| Confusion/disorientation |