The

mediastinum is the term used to describe the contents of the thorax between the pleural cavities. It is an anatomical region defined by the lungs laterally, the diaphragm inferiorly, the thoracic inlet superiorly, the sternum anteriorly, and the vertebral column posteriorly. It is densely populated with vital structures including, but not limited to, the heart and great vessels as well as the trachea and the esophagus. It has been described as the “third space” of the thorax or “the space between spaces.”

1Tumors of the mediastinum may originate from the normal anatomic structures of the region or from adjacent tissues. They may be primary or metastatic and they encompass a wide variety of histologies. This discussion will focus on mediastinal masses in adults.

COMPARTMENTS

There are numerous classification systems for the compartments of the mediastinum in the surgical and radiological literature. Perhaps the simplest and most clinically relevant system is that proposed by Shields,

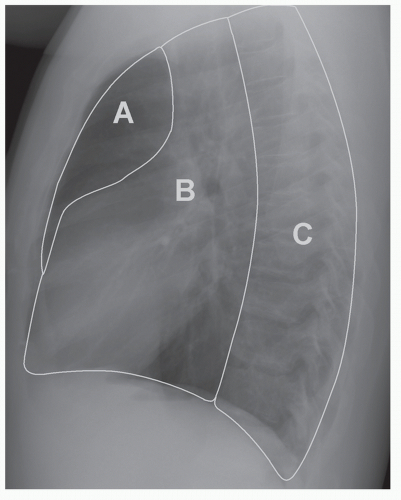

2 which subdivides the mediastinum into three anatomic compartments: the anterior, middle (or visceral), and the paravertebral sulci laterally. These compartments are readily depicted on a lateral view of the chest (

Fig. 66.1).

The anterior compartment contains the thymus gland, lymph nodes, connective tissue, and fat. It may also contain displaced parathyroid glands or ectopic thyroid tissue. The visceral (or middle) compartment contains the heart and great vessels within the pericardium, the esophagus, trachea, and portions of the mainstem bronchi, the thoracic duct, and numerous lymph nodes and nerves (vagus and phrenic). The paravertebral sulci (posterior compartment) contain the proximal portions of the intercostal nerves, arteries, and veins, as well as the sympathetic trunk.

The clinical relevance of the model lies in the differential diagnoses of masses in each compartment (

Table 66.1).

3

SIGNS AND SYMPTOMS

Approximately 50% of mediastinal masses in the adult population are found in asymptomatic patients.

4 Increased use of screening and surveillance CT scans and chest radiographs will likely raise the proportion of asymptomatic masses. In adults, the anterior mediastinum is the most common location for tumors.

Symptoms depend on the size and location of the mass. Malignant lesions are more likely to be symptomatic.

5 Although many symptoms are caused by local compression or invasion of adjacent structures, systemic symptoms associated with specific tumor types may also be present.

3Respiratory symptoms of cough, dyspnea, stridor, and hemoptysis are among the most common. Local invasion of pleura or chest wall may result in chest pain, which is often pleuritic in nature. Chest pain may also mimic angina. Other symptoms and signs resulting from local invasion or compression of structures includes dysphagia (esophagus), hoarseness (recurrent laryngeal nerve), superior vena cava (SVC) syndrome, Horner’s syndrome (stellate ganglion), and cardiac tamponade (pericardium).

Generalized symptoms associated with malignancies such as fever, chills, and weight loss also need to be considered. Symptoms and signs associated with specific endocrine tumors may also be present (

Tables 66.2 and

66.3). Signs and symptoms of hypercalcemia may be associated with parathyroid adenomas. The classical association of myasthenia gravis with an anterior mediastinal mass is almost pathognomonic of thymoma (not considered in this chapter). The presence of “café-au-lait” spots and a posterior mass is similarly suggestive of von Recklinghausen neurofibromatosis. Physical examination should include testicular assessment if a germ cell tumor (GCT) is suspected.

6

IMAGING

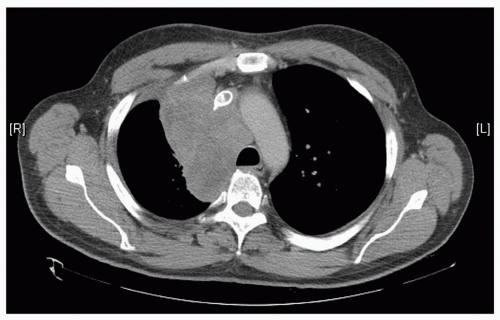

Radiology Although most patients will have a lateral and posteroanterior (PA) chest radiograph during their first examination, almost all patients will subsequently have a computed tomography (CT) scan. It is routine for computerized tomograms of the chest to image the area between the lung apices to the base of the adrenal glands. When mediastinal pathology is suspected, intravenous contrast should be used as it helps with lesion detection and definition. CT gives valuable information as to the density of the mass (cystic or solid) as well as its relationship to adjacent anatomic structures (

Fig. 66.2).

7

Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) is somewhat limited in evaluation of the thorax because of its sensitivity to motion artifact (from cardiac and respiratory movements) and poor imaging quality of lung parenchyma. In imaging of mediastinal masses, its greatest utility lies in its assessment of specific areas where CT may fall short. These may include cases where the patient is unable to tolerate contrast for CT. The most common indication for magnetic resonance (MR) is in assessment of masses in the paravertebral sulci or posterior compartment. MR is useful if there is a “dumbbell” component to

a neurogenic tumor (i.e., if the tumor has extended into the spinal canal). MR can give information as to the longitudinal extent of the involvement of the spinal canal.

8Ultrasound has limited use in the evaluation of mediastinal pathology. It is primarily used for localization during percutaneous biopsies.

Positron Emission Tomography Positron emission tomography (PET) has become an increasingly important tool in the investigation of malignancies throughout the body. This is true of mediastinal pathology as well (

Fig. 66.3). Most centers will routinely perform PET with

18F-fluorodeoxyglucose (FDG) in the evaluation of suspected non-small cell lung cancers (NSCLC) or esophageal cancers. PET also plays an important role in the evaluation of lymphoma. In both Hodgkin’s and non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma (NHL), PET has been found to be an accurate and cost-effective method of staging disease as well as monitoring responses to therapy and assessing recurrence.

9

The use of PET in the indeterminate mediastinal masses has not been well defined and requires further study. In one Japanese study, increased FDG uptake correlated with an increased likelihood of malignancy.

10Other Nuclear Imaging Techniques Octreotide, a somatostatin analogue, has been used in the evaluation of some suspected mediastinal pathology. It has an affinity for

neuoroendocrine neoplasms such as pheochromocytomas, medullary carcinomas of the thyroid, carcinoid tumors, small cell lung cancer, and some lymphomas.

11

Other nuclear imaging techniques may be relevant in the evaluation of other specific diagnoses. For example, parathyroid sestamibi scans can be used in the search for ectopic mediastinal parathyroid tissue or scintigraphy with an iodine isotope can be used for suspected mediastinal goiters. Gallium scanning plays a role in the staging of lymphoma.

11