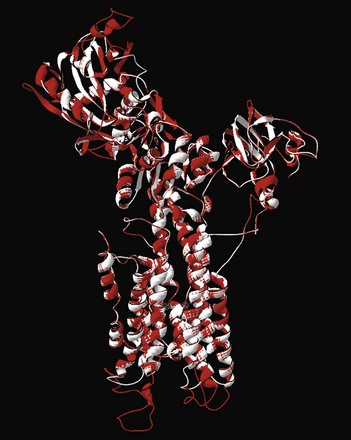

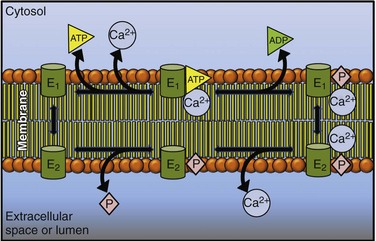

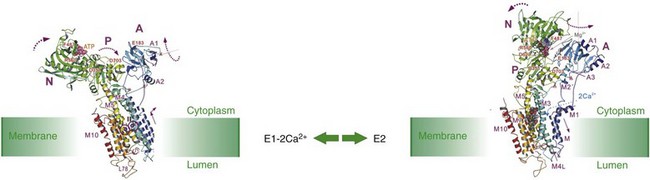

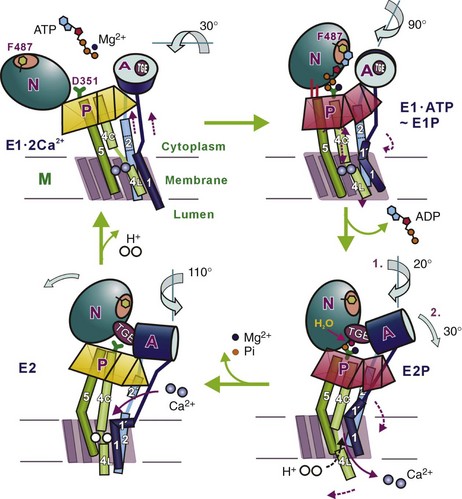

5 Ca2+-transporting adenosine triphosphatases (ATPases; Ca2+ pumps) have been described in animal and plant cells and in cells of lower eukaryotes. This chapter will focus on the ATPases of animal cells and on the disease processes linked to their dysfunction. The three animal Ca2+ pumps belong to the large superfamily of P-type ATPases, which have been so defined because their reaction cycle is characterized by the formation of an acid-stable phosphorylated Aspartate (Asp) residue (the P intermediate) in a highly conserved sequence (SDKTGT[L/IV/M][T/I/S]).1 The family now contains hundreds of members and eight subfamilies.2 The subfamilies have been identified based essentially on transported substrate specificity, the evolutionary appearance of which having been accompanied by abrupt changes in sequence. The changes, however, do not involve eight conserved structurally and mechanistically important regions that define the core of the superfamily. Five branches have been identified in the phylogenetic tree of the superfamily: two animal Ca2+ pumps belong to subgroup II A (the sarco/endoplasmic reticulum Ca2+ [SERCA] and secretory pathway Ca2+ [SPCA] pumps), one to subgroup II B (the plasma membrane Ca2+ [PMCA] pump). All P-type ATPases, including the three that transport Ca2+ in animal cells, are multidomain proteins that share the essential properties of the reaction mechanism, have molecular masses varying between 70 and 150 kDa, and share the presence of 10 hydrophobic transmembrane (TM) spanning domains (however, some have only six or eight). The number of TMs being even and the N- and C-termini of all P-type pumps are on the same membrane side (i.e., the cytosol); one exception is a splice variant of the SERCA pump that has 11 TM). The P-type ATPases also share the sensitivity to the transition state analog orthovanadate and, with some specific differences (see below), to La3+. Other inhibitors only affect selected members of the superfamily. The three-dimensional (3D) structures of four P-type ATPases have become available following the landmark solution of the 3D structure of the SERCA pump 12 years ago3: molecular modeling on templates of the SERCA pump structure has indicated that all P-type ATPases share the general principles of 3D structure. The reaction cycle of P-type ATPases originally envisaged only the E1 and E2 steps, characterized by distinct conformations and affinities for adenosine triphosphate (ATP) and the transported ion. For example, Ca2+ pumps in the E1 state engage Ca2+ with high affinity at one side of the membrane, and in the state their E2 lowered affinity for Ca2+ releases it to the opposite membrane side.4 Later, additional intermediate states were added that made the reaction cycle much more complex, but the basic E1/E2 nomenclature has been retained. Importantly, each step of the reaction cycle is reversible, so that ATP can be produced by reversing the direction of the ion transport process. Reversal of the SERCA pump, with production of ATP, had in fact already been demonstrated in one of the first experiments on the transport of Ca2+ by vesicular preparations of sarcoplasmic reticulum.5 A simplified version of the cycle, but adapted to Ca2+ pumps, is shown in Figure 5-1. Figure 5-1 A simplified reaction cycle of the P-type adenosine triphosphatases (pumps) adapted to the Ca2+ pumps. The two original conformational states of the pumps are envisaged. The E1 pumps bind Ca2+ with high affinity at one membrane side (the cytosol), the E2 pumps have much lower Ca2+ affinity, and release Ca2+ to the opposite membrane side. Adenosine triphosphate phosphorylates a conserved Asp in the active site. The SERCA pump is inhibited by La3+ and orthovanadate, and the discovery of specific inhibitors such as thaspigargin,6 cyclopiazonic acid,7 and 2.5-di(t-butyl)hydroquinone8 represented a significant advantage in the biochemical and structural characterization of the pump. The SERCA protein is organized in the membrane with 10 TMs: numerous mutagenesis studies and the solution of its 3D structure have clarified essential molecular details of its function, which will be summarized in this chapter. Full details are available in a number of more comprehensive reviews.9–11 Analysis of the 3D structure of the SERCA1 pump isoform has revealed that the single polypeptide chain folds in three cytosolic domains and in one transmembrane sector (M) composed of the 10 formerly predicted TMs (Figure 5-2). The three cytosolic domains have been named according to their role in the reaction cycle: the nucleotide binding domain (N) binds ATP, the phosphorylation domain (P) drives ATP hydrolysis leading the phosphorylation of the catalytic Asp, and the actuator domain (A) catalyzes the dephosphorylation of the P-domain. The A and P domains are connected to the transmembrane M domain that contains the 2 Ca2+ binding sites: the SERCA pump transports 2 Ca2+ per ATP hydrolyzed. The N domain is instead connected to the P domain. During the cycle, phosphorylation and dephosphorylation events promote conformational changes that control the access of Ca2+ to the two binding sites (site I and site II), which exist in high- and low-affinity states (Figure 5-3). The two sites are located near the cytoplasmic surface of the membrane, but site I faces the cytoplasmic side and site II is closer to the luminal side. Once Ca2+ becomes bound to site I, a conformational change increases the affinity of site II and permits the phosphorylation of the catalytic Asp by ATP, leading to the transition E2→E1→E1•2Ca2+ E1P. The binding of ATP crosslinks the P and N domains, permitting the interaction of P domain with the A domain, which rotates inducing the opening of the luminal gate that releases Ca2+ to the lumen and permits the E1P-E2P transition. The closure of luminal gate, and thus the E2P→E2 Pi transition, then occurs because a second rotation of the A domain locks it to the P domain. A highly conserved TGES motif in the A domain fills the gap between the N and P domains after the second rotation of the A domain, eventually permitting the release of Ca2+ into the lumen. The rearrangements of transmembrane helices M1-M6 induced by the rotation of the A domain allow protons and water molecules to enter and stabilize the empty Ca2+ binding sites. The rearrangements also induce the retraction of the TGES from the phosphorylation site and the entrance of one water molecule to the phosphorylation site, inducing the release of phosphate (and Mg2+) and the complete closure of the luminal gate. Figure 5-2 The three-dimensional structure of the SERCA pump, showing the open configuration of the three cytoplasmic domains A, N, and P in the presence of Ca2+, and the more compact configuration of the cytosolic sector in its absence. The two purple spheres in the upper panel represent the two bound Ca2+. The E2 structure shown contains the inhibitor thapsigargin (TG). The TMs are the transmembrane domains. Several residues of importance not discussed in the text are also shown. (Modified from Toyoshima C: Structural aspects of ion pumping by Ca2+-ATPase of sarcoplasmic reticulum. Arch Biochem Biophys 476:3–11, 2008.) Figure 5-3 The conformational changes of the cytosolic and membrane domains of the SERCA pump during the transport of Ca2+ across the molecule. (Modified from Toyoshima C: Structural aspects of ion pumping by Ca2+-ATPase of sarcoplasmic reticulum. Arch Biochem Biophys 476:3–11, 2008.) The SERCA2a pump is the major isoform of developing and adult mammalian heart (SERCA2b is also expressed there, its level being unchanged during the development).12 SERCA2a is the most abundant protein in the heart membrane; its increased sarcoplasmic reticulum (SR) expression during the development paralleled the increasing rate of Ca2+ uptake by the SR lumen and the shortening of the relaxation time in adults, with respect to neonatal heart. SERCA2a pump levels are higher in atria than in ventricles, partially accounting for the shorter duration of contraction in atrial than in ventricular tissues. The expression and the activity of the SERCA2a pump have been studied extensively. The primary mechanism of the regulation of the pump is mediated by phospholamban (PLB).13 PLB is a 52-residue protein composed of a hydrophobic helical C-terminal portion inserted into the SR membrane and a hydrophilic N-terminal region that protrudes into the cytosol and contains phosphorylation sites (Ser16 and Thr 17) for PKA and, possibly, CAMKII. Dephosphorylated PLB binds to the pump, decreasing its Ca2+ affinity; phosphorylation by PKA, and possibly CaMKII, releases the inhibition and increases the affinity of the pump for Ca2+ and thus Ca2+ transport. The hydrophilic N-terminal portion of PLB interacts with a domain close to the active site of the pump and, within the membrane, with transmembrane helices 2, 4, 6, and 9. It is generally believed that PLN exists both as a pentamer and a monomer. It is not clear how the conversion between the two forms occurs, but several lines of evidence indicate that monomeric PLB is the active form. However, structural observations indicate that pentamers can also interact with the pump.14 Another small (31 residues) transmembrane protein, sarcolipin (SLN), originally identified as it copurified with the SERCA1a pump, has recently also received attention. SLN is predominantly expressed in the atrial compartment of the heart, and its sequence is similar to that of the transmembrane sector of PLN. Modeling studies have revealed that the SLN and PLB interactions with the SERCA pump may be similar—that is, SLN would bind to the pump in transmembrane sites of PLB.14 Studies on SLN are still limited, but SLN overexpression in ventricle cells of animal models, where SLN is essentially absent, caused a decrease in the Ca2+ affinity of SERCA2a and slowed relaxation, suggesting that SLN is as effective an inhibitor of SERCA pump activity as PLB. Interestingly, the overexpression of SLN in the heart of PLB-null mice caused a decrease in the affinity of the SERCA2a pump for Ca2+ and impaired contractility. The finding that isoproterenol, a β-adrenergic agonist, relieved the inhibition suggests that SLN could mediate the β-adrenergic response in the heart. Ablation of the SLN gene increases the affinity of the SERCA pump for Ca2+, resulting in enhanced rates of SR Ca2+ uptake.15 The SERCA2b pump shares 85% sequence identity with the SERCA1a counterpart but differs functionally from it and from the SERCA2a isoform, which is characterized by a unique C-terminal extension—the so-called 2b-tail, which forms a luminal sequence extension and an additional TM segment (TM11).16 The extension has regulatory properties: the longer pump has a twofold higher affinity for cytosolic Ca2+ and a lower maximal turnover rate. According to a model based on the SERCA1a structure, and on the NMR structure of TM11, the interaction of TM11 with TM7 and TM10 has been proposed to stabilize the pump in the Ca2+-bound E1 conformation, with the high-affinity Ca2+ binding sites facing the cytosol. The TM11 has also been proposed as a novel regulator of the SERCA pump. The co-reconstitution of the 18-residue long TM11 with the SERCA1a protein in vitro reduced the maximum reaction rate (Vmax) and increased the Ca2+ affinity of the latter. The regulation of the SERCA pump by PLB and SLN, and by the 2b-tail in the 2b variant, resembles the interaction of the β- and γ-subunits of the Na+/K+-ATPase with the catalytic subunit α. The regulation also resembles the regulatory interaction of the PMCA pump with calmodulin, suggesting operationally similar molecular mechanisms of P-type pump regulation.17 In addition, the C-terminal portion of the ePMCa pump can to some extent replace PLB as an inhibitor of the SERCA pump. Apart PLB and SLN, which are the best-studied regulators of the SERCA pump, other proteins interact with the pump. Those interacting at the luminal side have an important role. The two chaperones calreticulin and calnexin contain a globular N-domain that binds carbohydrates—an extended P-domain that mediates the binding of ERp57 and an acidic C-terminal domain, that in the case of calreticulin binds 25 mol of Ca2+ per molecule of protein with low affinity (Kd, 2 mM). Luminal Ca2+ buffering by calnexin is less significant, and the acidic C-terminus of the protein protrudes into the cytosol. Calreticulin and calnexin have been suggested to interact through their N-domain with a putative glycosylated residue present in the C-terminal tail of the SERCA2b pump, but absent in SERCA2a. Glycosylation-independent interaction with the SERCA2b pump has been shown to occur, and molecular modeling of the SERCA2b molecule has suggested that its 2b-tail is located in luminal loops, thus making it inaccessible to interacting proteins. ERp57, a member of the PDI family of proteins with thio-oxidoreductase activity, is recruited by the SERCA2b pump–chaperone complex to catalyze the formation of an inhibitory disulfide bridge between Cys875 and Cys887 in the luminal loop L7-8 of the SERCA2b pump.18 The formation of a disulfide bridge could be a regulatory mechanism, but the proposal is controversial, because mutations of either or both Cys residues resulted in the loss of Ca2+ transport but not of the activity in SERCA1.19 Two additional luminal Ca2+ binding proteins have been shown to interact with the SERCA2 pump: the ubiquitously expressed calumenin and the histidine-rich Ca2+-binding protein (HRC). Both decrease the apparent Ca2+ affinity of the pump. HRC binds Ca2+ with high capacity and low affinity and could mediate both SR Ca2+ uptake and release through its interaction with SERCA, when the SR Ca2+ is low, and with triadin, which is part of the RyR Ca2+ release complex when it is saturated by Ca2+.20 The Golgi Ca2+ ATPase (the SPCA pump) shares with the SERCA pump the role of loading Ca2+ in the Golgi apparatus.21,22 The relative contribution of the SPCA and SERCA pumps to the total Ca2+ uptake in the Golgi apparatus is cell-type dependent. The use of the SERCA pump selective inhibitor thapsigargin, which does not inhibit the SPCA pump, has confirmed that the SERCA pump contribution is significant in numerous cell types, but not in keratinocytes that mainly use the SPCA pump. This point is interesting because SPCA pump mutations that impair the function of the pump lead to a specific human disease, Hailey-Hailey disease (discussed later). In contrast to the SERCA pump, the SPCA pump also transports Mn2+ and thus serves the dual function of supplying this metal to the Golgi lumen, where it acts as a cofactor for the glycosyl-transferases, and to remove it from the cytosol, where its accumulation could be toxic. The Golgi Ca2+ ATPase was originally discovered in yeast and named Pmr1 (plasma membrane ATPase-related) and PMA1 (plasma membrane H+-ATPase) by two independent groups. Later, it was detected in mammals and higher vertebrates. The SPCA pump is also predicted to be organized in 10 TMs, with a large headpiece portion protruding into the cytosol. On the basis of the SERCA pump 3D structure, the cytosolic portion is divided in the three canonical A, P, and N portions (Figure 5-4). The SPCA pump is shorter than the SERCA and PMCA pumps, because it does not have the long cytoplasmic C-terminal tail of the PMCA pump, and its intracellular loops are shorter. The SPCA pump differs from the SERCA pump in having only one Ca2+ binding site, corresponding to site II in the SERCA1 pump. The suggested TM packing and possibly some distant residues would define the structure of the site, making it adequate to bind Mn2+ with high affinity and to transport it. This structural aspect is a peculiarity of the SPCA pump. Gln783 in TM6 and Val335 in TM4 appear to be essential for Mn2+ transport, because their mutation (in the Pmr1 yeast pump) abolished Mn2+ transport. Another distinction of the SPCA pump with respect to the SERCA and PMCA pumps, which function as obligatory H+ exchangers, is the finding that it does not appear to countertransport H+. No specific SPCA pump inhibitors have been described, and no endogenous activators are known. Mutagenesis studies on the Pmr1 yeast pump have generated phenotypes that are important tools that could provide information on the role of the SPCA pump in higher eukaryotic organisms. The expression levels and activity of SPCAs change in response to altered physiologic needs. SPCA1 pump expression and activity changed in the brain after an ischemic event,23 and the SPCA1 pump levels increased in mammary gland during lactation. This last finding is shared by the PMCA2 pump (discussed later). The role of the SPCA pump in the maintenance of Golgi Ca2+ homeostasis deserves a comment, because recent evidence have indicated that the Golgi apparatus is a heterogeneous and highly dynamic Ca2+ store.24 The apparatus has been shown to be an InsP3-sensitive Ca2+ store, implying a role for it in the generation of local cytosolic Ca2+ signals. The specific distribution of the SPCA pump in the Golgi membranes appears important; it can vary with the cell type (i.e., in some cases it colocalizes with Golgi markers and in others with those of the trans-Golgi). However, a consensus has now been reached that the SPCA1 pump–containing Golgi subcompartment is insensitive (or mildly sensitive) to InsP3, and thus appears not to be involved in generating cytosolic Ca2+ signals. The kinetics of Ca2+ release from the Golgi apparatus differed from those of the ER. In particular, although the latency following agonist application and the initial rate of Ca2+ release were similar for the two organelles, the release of Ca2+ from the Golgi apparatus terminates faster than that from the ER. These findings would be compatible with distinct Ca2+ subcompartments in the Golgi apparatus endowed with differentCa2+ regulating molecular components.

Mammalian Calcium Pumps in Health and Disease

Sarco/Endoplasmic Reticulum Ca2+ ATPase

Secretory Pathway Ca2+ ATPase

Mammalian Calcium Pumps in Health and Disease