Malignant Pericardial Effusions

Deepak Singh

Mark R. Katlic

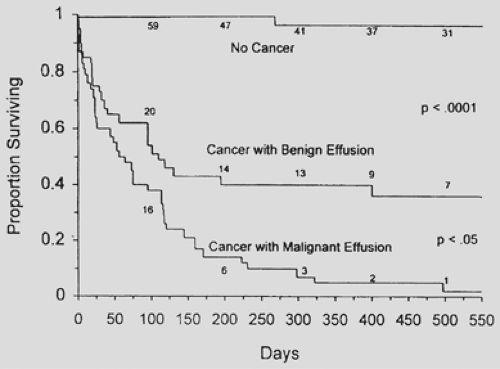

Malignant pericardial effusion is often a clinically challenging entity. A malignant effusion specifically is an accumulation of fluid in the pericardial sac associated with malignant cells in either the effusive fluid or the pericardium or epicardium. This entity is entirely different from malignancy-associated pericardial effusions, which do not include malignant cells but occur in patients with cancer. Approximately 50% of pericardial effusions in patients with known malignancy are benign.17,18 There is a significant survival difference in patients with true malignant effusion versus benign malignancy-associated pericardial effusion (Fig. 72-1). It is therefore important to distinguish the two in treating pericardial effusion and selecting treatment modalities.

The clinical manifestation of malignant pericardial effusions can be mercurial, ranging from asymptomatic to hemodynamic collapse secondary to cardiac tamponade. Many of the symptoms are nonspecific and are easily confused with other cancer-related illnesses. Because of this, the diagnosis is often made late in the course of the progression of malignant effusions, when the patient is gravely ill. It is not uncommon for a patient with malignant pericardial effusion to present with tamponade.8

How do we diagnose this often subtle harbinger of cancer progression? How do we best ameliorate its potentially life-threatening mechanical effects?

Prevalence and Pathophysiology

Prevalence

The best estimate of prevalence of malignant pericardial effusion comes from autopsy data, as many patients with subclinical effusions go undiagnosed. Klatt and Heitz11 reported 28 patients with malignant pericardial effusion among 1,029 autopsies on patients with known malignancy, giving a prevalence of 3%. However, other series have reported prevalences up to 20%.13

Many types of cancers have been reported as metastasizing to the pericardium/epicardium to produce malignant pericardial effusions. The most frequently associated cancers are non-small-cell lung cancer (NSCLC), breast cancer, and lymphoma27 (Table 72-1).

Pathophysiology

Multiple mechanisms are felt to be at play in producing malignant pericardial effusions. The primary mechanism is thought to be obstruction of normal lymphatic flow and drainage. Malignant cells can spread to the pericardial or epicardial surfaces by direct extension, by hematogenous spread, and by lymphatic channels. Within the pericardium, the malignant cells, in addition to obstructing lymphatic channels, can interfere with endothelial cell function and consequently increase the accumulation of pericardial fluid. Metastatic infiltration of mediastinal lymph nodes can also produce pericardial effusions by blocking normal drainage. Finally, tumor cells may also provoke an increased effusive response from mesothelial cells of the pericardium.

It is important to note that tamponade is a mechanism that impedes cardiac filling despite compensatory mechanisms. The rate at which pericardial fluid accumulates is the most crucial factor in the development of tamponade. Even a small effusion can cause hemodynamic collapse if the accumulation is rapid. On the other hand, a very large asymptomatic effusion can develop if the rate of accumulation is slow (Fig. 72-2).

Clinical Presentation

The common symptoms of pericardial effusion include dyspnea (85%), cough (30%), orthopnea (25%), and chest pain (20%). The common signs of pericardial effusion are a paradoxical pulse (45%), tachypnea (45%), tachycardia (40%), hypotension (25%), and peripheral edema (20%). A chest radiograph will show an enlarged cardiac silhouette in more than 90% of patients, with accompanying pleural effusions in 50% of patients. An electrocardiogram will show low voltage in the limb leads in 55% of patients.8,11,13,17

A confusing factor in the clinical presentation of malignant pericardial effusion is that these patients will often have pleural effusion, which can produce similar symptoms. In multiple series, the incidence of pleural effusion concomitant with malignant pericardial effusions was in excess of 85%.19,25 As a result, none of these symptoms are pathognomonic for malignant pericardial effusion. Unfortunately, many patients with malignant pericardial effusion will present in tamponade. Tamponade was the initial presentation in 35% of patients in one reported series8 and in 50% of patients in another.5

Diagnosis

Nonspecific findings (e.g., cardiomegaly and/or pleural effusion on chest radiograph, low voltage on electrocardiogram) are

often noted on the initial tests in evaluating a symptomatic patient. The diagnosis of a pericardial effusion therefore requires documentation by either echocardiography or computed tomography (CT). In addition, many asymptomatic patients have effusions noted on echocardiography or CT that do not require any specific therapy.

often noted on the initial tests in evaluating a symptomatic patient. The diagnosis of a pericardial effusion therefore requires documentation by either echocardiography or computed tomography (CT). In addition, many asymptomatic patients have effusions noted on echocardiography or CT that do not require any specific therapy.

CT and magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) will often demonstrate the presence of an effusion. Newer models of CT or MRI scanners can now also give functional data as to the presence of tamponade. These devices, however, are not readily available at all facilities.

Table 72-1 Etiology of Pericardial Tamponade in 117 Patients | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Echocardiography is the single most useful tool in making the firm diagnosis of pericardial effusion. The test is easily performed at the bedside, is noninvasive, easily available, and typically the most cost-effective study. Information such as the size of effusion as well as its location and character can be evaluated by echocardiography. Echocardiography can also tell us about the epicardium of the heart and whether the effusion is circumferential or loculated (important in planning a surgical approach). The presence of tamponade or signs of it can be evaluated by echocardiography. Signs often looked for are diastolic collapse of the right ventricle or atrium (atrial collapse is less sensitive than ventricular collapse) or respiratory variation across the mitral valve or tricuspid valve (in M-mode imaging).

By definition, malignant pericardial effusion necessitates the presence of malignant cells in either the fluid cytology or pericardial tissue histology. Generally the best approach to obtaining a diagnosis will be through a surgically placed window,

particularly in a symptomatic patient. This would allow for both a diagnostic and therapeutic maneuver in one. However, in appropriate patients a pericardiocentesis may yield the answer.16

particularly in a symptomatic patient. This would allow for both a diagnostic and therapeutic maneuver in one. However, in appropriate patients a pericardiocentesis may yield the answer.16

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree