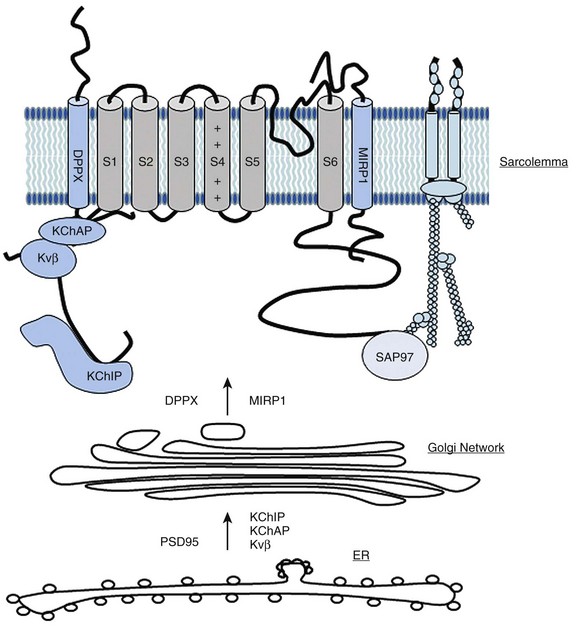

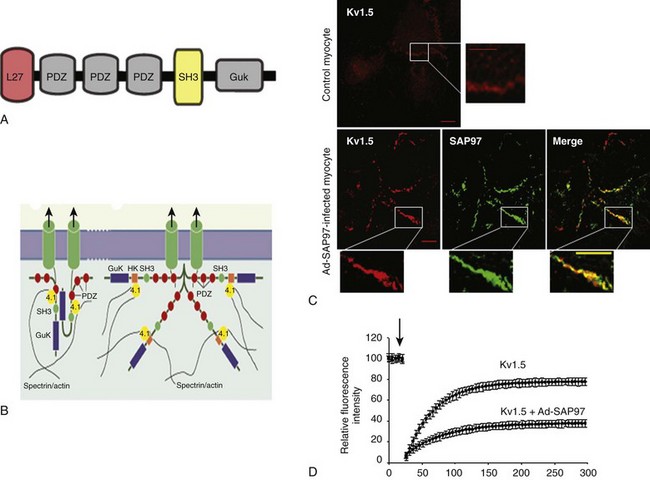

20 The first identified auxiliary subunits of potassium channels are the so-called Kvβ–subunits, which associate with the pore-forming Kv channels (referred as α-subunits). Initially purified from bovine brain,1,2 nine β-subunits encoded by four genes have been identified. In mammals, three genes are expressed in the heart and variants from alternative splicing are also found. Kvβ-subunits are localized in the cytosol with a conserved carboxy-terminal and a variable amino-terminal. Only the Kvβ1.1, Kvβ1.2, and Kvβ1.3 are expressed in the heart.3 Two main roles have been described for Kvβ subunits. It has been reported that Kvβ1 and Kvβ3 associate early with α-subunits during their biosynthesis in the endoplasmic reticulum and exert a chaperone-like effect, facilitating their stable expression at the plasma membrane.4,5 The C-terminal domain of Kvβ interacts with the α-subunit (stoichiometry of 1α-1β) to regulate channel trafficking. However, this chaperone-like property of the Kvβ-subunits has not been found for all Kv channels6,7 (Figure 20-1). Figure 20-1 Main partners of Kv4 channels from their synthesis and assembly to their organization in macromolecular complexes at the plasma membrane of cardiac myocytes. DPP, Dipeptidyl aminopeptidase-protein; ER, endoplasmic reticulum; KChAP, K channel associated protein; KChIP, K channel interacting protein; MIRP1, MinK related peptide. The most dramatic effect of Kvβ on the voltage-dependent outward current is to accelerate its rate of inactivation. Kv channels inactivate through two main mechanisms: the slow C-type inactivation and the rapid N-type inactivation called the ball-and-chain mechanism.8 An example of a Kv channel undergoing C-type inactivation is Kv1.5, which does not have an N-terminal domain acting as an open channel blocker. Kv1.5 is inactivated through a mechanism that involves slow conformational changes of the outer mouth of the pore, referred to as C-type inactivation. The coexpression of Kvβ1 with Kv α-subunits with C-type inactivation results in a fast inactivating current with increased membrane depolarization. For example, the Kv1.5-encoded current, one main component of IKur in atrial myocytes, is transformed by Kvβ1.3 subunits in a transient outward Ito-type current.9 This effect on current kinetic is associated with a shift of the voltage-dependent activation and inactivation to more negative potentials. The effect of Kvβ1 on channel inactivation is mediated by their N-terminal domain that blocks the inner cavity of the pore of the α-subunit resembling the ball-and-chain process.8,10 In addition, by binding to the C-terminus of the channels, Kvβ can accelerate the C-type inactivation.11 In heterologous expression systems, coexpression of Kvβ1.3 with Kv1.5 is necessary for the PKA (cAMP-dependent protein kinase)-mediated increase in K+ current. Moreover, PKC has little effect on Kv1.5 channels alone; however, when coexpressed with the Kvβ1.2, the protein kinase reduces the K+ current.12 These observations are consistent with the presence of multiple phosphorylation sites on the β- and α-subunits13 and could provide an explanation for the effects of β-adrenergic or PKC stimulation on IKur in human atrial myocytes.14 The characteristics of repetitive membrane depolarizations (i.e., their duration and frequency) can modify persistently the rate of inactivation of Ikur in human atrial myocytes. This effect is modulated by the activation of CaMKII (calcium-calmodulin dependent protein kinase-II) and could also involve the interaction between Kvβ and the Kvα1.5 subunits.15 Another illustration of the important role played by the regulation of Kv channels by Kvβ is provided by the study on pharmacological properties of the Kv1.5 channel. The contribution of Ikur to shortening of the AP during atrial fibrillation16–19and the fact that Kv1.5 channel is more abundantly expressed in atrial than ventricle myocardium, explain the effort to develop selective IKur blockers as potential atria-specific antiarrhythmic agents. Some of these molecules compete with β-subunits to bind to the inner cavity of the Kv1.5 channel pore and are responsible for an apparent open channel block of Ikur. For example, Kvβ1.3 decreases drug affinity of Kv1.5 for local anesthetic and antiarrhythmic drugs (e.g., bupivacaine,20,21 AVE0118,22 vernakalant23). In atrial myocytes as well, the analog of tedisamil (i.e., bertosamil) accelerates the rate of inactivation of the outward current with membrane depolarization, consistent with a competition between the drug and endogenous Kvβ at the inner face of the pore.24 Finally, an oxidoreductase activity has been reported for Kvβ subunits as indicated by the observation that Kvβ2.1 confers sensitivity to oxygen to Kv4.2.25 This enzymatic activity is likely due to the presence of a binding site for the cofactor NADP+ and catalytic domains; however, in vivo data are lacking. Originally thought to be the α-subunit of the delayed potassium current Iks, minK (for minimal K channel protein)26 is a small transmembrane protein (14–20 kDa) encoded by KCNE1. The first interaction described for minK is with the Kv7.1 channel (KvLQT1). Expressed alone, Kv7.1 underlies a voltage-dependent outward current of low amplitude. In contrast, when coexpressed with minK, this channel is responsible for a large, slow, delayed-type current—Iks.27,28 MinK can interact with other channels like hERG (or Kv11.1), which is responsible for the activation of the rapid delayed rectifier, Ikr, but this observation was obtained only in heterologous expression systems. In mice, deletion of KCNE1 is associated with an impaired QT-RR adaptability on the electrocardiogram (ECG), prolongation of epicardial AP duration, and frequent episodes of atrial tachycardia29,30 indicating the physiologic importance of this ancillary subunit in cardiac electrophysiology. Four other peptides belonging to the minK family have been identified and called MinK- and MinK-related protein (MiRP; for MinK related peptide, KCNE2-5).7 In the heart, MiRP1 (KCNE2) is expressed mainly in the nodal tissue and Purkinje cells. In vitro, MiRP1 can interact with several potassium channels, including Kv7.1,31 Kv4,32 and hERG.33 The hERG channel is regulated by cyclic adenosine monophosphate (cAMP)-dependent protein kinase, PKA, which increases the current amplitude through the shift of the voltage-dependent activation of the channels. This pathway is an important target for sympathetic regulation and the subsequent adaptation of cardiac repolarization to increased heart rate. It has been reported that KCNE2 facilitates the PKA regulation of Ikr by stabilizing hERG in its phosphorylated form.34 Transgenic models have contributed to establish the physiologic role of MiRP1 in the heart. Mice with specific deletion of the KCNE2 gene show prolonged ventricular APs and reduced density of the fast and slow components of the outward potassium current in keeping with KCNE2 interacting with various potassium channels.7,35 Genetic studies of patients suffering from inherited or drug-induced long QT syndrome have provided also important information on the physiologic role of this family of potassium partners. Mutations of genes encoding minK and MiRP1 have been found during the familial form of long QT syndrome, LQT5 and LQT6, respectively.33 Some mutations of KCNE2 are responsible for the decrease in Ikr due the acceleration of hERG inactivation. This results in less repolarizing current during the termination of the AP causing the prolongation of the phase 3 and a risk of triggered activities.36 Other mutations have been shown to modify the pharmacologic profile of hERG providing a molecular explanation for iatrogenic long QT syndrome and torsade de pointe33,37,38 (see Figure 20-1). K+ channel interacting protein (KChIP) is another important family of ancillary subunits of K+ channels. They are encoded by four genes, KChIP1-4 generated and alternative splicing. KChIP isoforms differ by their N-terminus, whereas they share 70% of homology, notably with four conserved “EF-hand-like” domains that bind Ca2+.39 Only KChIP2 is expressed in the heart. The C-terminus of KChIP2 interacts directly at the cytosolic face of the membrane with the N-terminus of Kv4 channels, characterized by a rapid N-terminal inactivation. In expression systems, the interaction of KChIP with Kv4 α-subunits is associated with a marked increase in the amplitude of Ito,f,39,40 an effect attributed to the capacity of KChIP to prevent the retention of Kv4 α-subunits in the endoplasmic reticulum (ER).40 The other effect of KChIP on Kv4 channels is to regulate their rate of inactivation and recovery from inactivation.39,40 Of note, the three cardiac isoforms of KChIP2 differ in their effects on the functional expression and gating properties of potassium channels and might not have the same regulatory effects on cardiac electrophysiology7 (see Figure 20-1). Endocardial myocytes are characterized by APs of longer duration than epicardial APs. This gradient of repolarization from endocardium to epicardium is essential for the oriented propagation of the depolarization wave, the prevention of retrograde activation of the myocardium, and the risk of arrhythmogenic reentry. In mammals, the epicardial-to-endocardiac gradient is due to regional differences in density of the fast component of the transient outward current, Ito,f, the highest density of Ito,f has been observed in myocytes of the epicardial layer.41,42 In large mammals such as humans, Kv4.3 is the predominant molecular basis of Ito,f. This channel is homogenously distributed in the ventricular wall and cannot explain the gradient of Ito,f.41,42 In contrast, both at the transcript and protein levels, the concentration of KChIP2 increases from endocardium to epicardium. This gradient is likely to contribute to the gradual expression of Ito,f in human and dog ventricles.43,44 In rodents, the gradient of repolarization is not due to KChIP, but to the gradual expression of Kv4.2 between the endocardium and epicardium. However, despite such species specificities, mouse models have contributed to establish the importance of KChIP2 in the normal activation of voltage-dependent outward current Ito, which is suppressed in KChIP2 knockout mice.45 A third partner that contributes to the formation of the Kv4 macromolecular complex is the transmembrane dipeptidyl aminopeptidase-protein (DPP). This integral transmembrane protein interacts with the extracellular matrix, and either separately or jointly with KChIP associates with Kv4 subunits at the N-terminus to modulate the trafficking and targeting of the channel46 (see Figure 20-1). Only a few studies have been conducted on the K channel associated protein (KChAP). This small protein of 574 amino acids expresses in the heart. It is a cytoplasmic subunits that interact transiently with several voltage-dependent Kv channels, including Kv1.x, Kv2.1, and Kv4.3.47,48 In vitro, KChAP upregulates Kv channel’s surface expression through a chaperone effect47,48 (see Figure 20-1). In 1995, Kim et al.49 reported that neuronal Shaker channels are clustered by a protein (PSD95) belonging to a family of multi-domain membrane proteins, called the membrane-associated guanylate kinase homologs (MAGUK proteins). Since that early study was published, a number of channels have been found to interact with MAGUK proteins in different tissues, including the heart.49a These anchoring proteins are viewed as central organizers of specialized plasma membrane domains, such as the intercalated disc of cardiac myocytes. The presence of several protein-protein interacting domains is the hallmark of MAGUK proteins such as an Src homology 3 domain, a GUK domain with homology to the enzyme guanylate kinase, and one or several Post Synaptic Density Protein, Drosophila disc large tumor suppressor, Zonula occludens (PDZ) domain(s). Most MAGUK proteins contain three PDZ domains. The PDZ domain of MAGUK proteins expressed in the heart recognizes a C-terminal–Ser/thr-X-ψ–Val sequence, where X refers to any amino acid and ψ refers to an hydrophobic amino acid50,51 (Figure 20-2). Figure 20-2 The anchoring protein SAP97 of the MAGUK family. A, Molecular organization of MAGUK proteins. B, Scheme of possible interactions of MAGUK protein and with potassium channels. C, The overexpression of SAP97 (Ad-SAP97) is associated with the accumulation of GFP-tagged Kv1.5 channels at the level of plasma membrane. D, The immobilization of Kv1.5 channel in cardiac myocytes. (From Abi-Char J, El-Haou S, Balse E, et al: The anchoring protein SAP97 retains Kv1.5 channels in the plasma membrane of cardiac myocytes. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol 294:H1851–H1861, 2008.) Several MAGUK proteins are expressed in the heart: SAP97, ZO-1, CASK, and MAGI3. For example, the gap junction channel, connexin 43, interacts with zonula occludens-1 (ZO-1), which regulates its localization at the intercalated disc and probably also its internalization.52–54 An additional cardiac MAGUK protein that has been studied extensively is SAP97. In atrial and ventricular myocytes, SAP97 is predominantly localized at the intercalated disc.55–60 In vitro, it has been shown that SAP97 is targeted exclusively at the level of myocyte-myocyte contacts in membrane domains, such as adherens and gap junctions.61 SAP97 is also present at the adrenergic synapse in myocytes, facing the nerve endings; therefore, it is part of the β-adrenergic signaling complex.62 These results indicate that SAP97 is an important determinant of the targeting of potassium channels in specialized cell-cell contact domains of the sarcolemma. The MAGUK SAP97 interacts with several cardiac ion channels including Nav1.5,60 Kir2.x, Kv4.x, Kv1.5, HCN-2, and HCN-4.*

Macromolecular Complexes and Cardiac Potassium Channels

The Four General Classes of Accessory Subunits

Kvβ Family

MinK and MinK-Related Proteins

K+ Channel Interacting Protein

K Channel Associated Protein

The MAGUK Proteins

![]()

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree

Thoracic Key

Fastest Thoracic Insight Engine